User login

‘I can handle it’– The state of hospitalist group backup systems

It took my hospital medicine group (HMG) 20 years to implement a formal backup system. Of all the reasons we resisted creating a backup system, foremost was that we did not want to mandate additional work. Because our compensation model did not have a mechanism to financially reward hospitalists for unexpectedly having to come in on unscheduled work days (other than the work relative value units generated by seeing patients), there was not enough motivational energy to get a system started.

It turns out our group is not unlike many other HMGs across the nation. According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM), 58.3% of adult-only HMGs, 72.2% of pediatric-only HMGs, and 52.6% of HMGs serving both adults and children did not have staffing backup systems. Interestingly, the report also showed that for groups serving adults only, academic HMGs were more likely to have formal backup systems in place (62.6%, compared with 37.3% in nonacademic HMGs).

The reason most HMGs create backup systems is to have a consistent and fair approach for dealing with unanticipated absences and/or high-volume census. In addition to creating a safety net, implementing a backup system addresses the common problem of the same hospitalists disproportionately filling in during times of crisis.

Although our group created a formal backup system starting January 2015, it is not comprehensive and deals only with high patient volumes occurring during the late evening and night hours. Hospitalists rotate through a schedule, taking a week of backup call for which no additional compensation is offered. Then, if they are actually called to come in, an hourly stipend is paid in addition to work RVUs generated. Implementing a backup system was not necessarily a popular idea. Nevertheless, the system has successfully remained in place. Triggering the system infrequently, having a clear set of criteria for when to activate backup, and providing additional compensation for the additional work are key factors in our system’s success.

When data from the 2016 SoHM report are compared with the 2014 SoHM report, the proportion of groups with formal backup systems actually decreases for both adults-only HMGs and HMGs serving both adults and children. For adult-only HMGs, there was a decline to 41.8% from 57.6%. For adult/pediatric HMGs, there was a decline to 47.4% from 58.8%. It also is notable that pediatric HMGs in particular are much less likely to have formal backup systems, only 27.8%, which has changed little since the last survey (28.8 % in 2014).

All in all, the reasons for the decline in backup systems are unclear. Possibly, the decrease is because of issues surrounding compensation, as approximately one-third of survey respondents with backup systems received no additional compensation. But in my view, it’s more likely that the reason for the decreased percentage of groups with backup systems has to do with differences in the particular set of HMGs that responded to the survey this year.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

It took my hospital medicine group (HMG) 20 years to implement a formal backup system. Of all the reasons we resisted creating a backup system, foremost was that we did not want to mandate additional work. Because our compensation model did not have a mechanism to financially reward hospitalists for unexpectedly having to come in on unscheduled work days (other than the work relative value units generated by seeing patients), there was not enough motivational energy to get a system started.

It turns out our group is not unlike many other HMGs across the nation. According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM), 58.3% of adult-only HMGs, 72.2% of pediatric-only HMGs, and 52.6% of HMGs serving both adults and children did not have staffing backup systems. Interestingly, the report also showed that for groups serving adults only, academic HMGs were more likely to have formal backup systems in place (62.6%, compared with 37.3% in nonacademic HMGs).

The reason most HMGs create backup systems is to have a consistent and fair approach for dealing with unanticipated absences and/or high-volume census. In addition to creating a safety net, implementing a backup system addresses the common problem of the same hospitalists disproportionately filling in during times of crisis.

Although our group created a formal backup system starting January 2015, it is not comprehensive and deals only with high patient volumes occurring during the late evening and night hours. Hospitalists rotate through a schedule, taking a week of backup call for which no additional compensation is offered. Then, if they are actually called to come in, an hourly stipend is paid in addition to work RVUs generated. Implementing a backup system was not necessarily a popular idea. Nevertheless, the system has successfully remained in place. Triggering the system infrequently, having a clear set of criteria for when to activate backup, and providing additional compensation for the additional work are key factors in our system’s success.

When data from the 2016 SoHM report are compared with the 2014 SoHM report, the proportion of groups with formal backup systems actually decreases for both adults-only HMGs and HMGs serving both adults and children. For adult-only HMGs, there was a decline to 41.8% from 57.6%. For adult/pediatric HMGs, there was a decline to 47.4% from 58.8%. It also is notable that pediatric HMGs in particular are much less likely to have formal backup systems, only 27.8%, which has changed little since the last survey (28.8 % in 2014).

All in all, the reasons for the decline in backup systems are unclear. Possibly, the decrease is because of issues surrounding compensation, as approximately one-third of survey respondents with backup systems received no additional compensation. But in my view, it’s more likely that the reason for the decreased percentage of groups with backup systems has to do with differences in the particular set of HMGs that responded to the survey this year.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

It took my hospital medicine group (HMG) 20 years to implement a formal backup system. Of all the reasons we resisted creating a backup system, foremost was that we did not want to mandate additional work. Because our compensation model did not have a mechanism to financially reward hospitalists for unexpectedly having to come in on unscheduled work days (other than the work relative value units generated by seeing patients), there was not enough motivational energy to get a system started.

It turns out our group is not unlike many other HMGs across the nation. According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM), 58.3% of adult-only HMGs, 72.2% of pediatric-only HMGs, and 52.6% of HMGs serving both adults and children did not have staffing backup systems. Interestingly, the report also showed that for groups serving adults only, academic HMGs were more likely to have formal backup systems in place (62.6%, compared with 37.3% in nonacademic HMGs).

The reason most HMGs create backup systems is to have a consistent and fair approach for dealing with unanticipated absences and/or high-volume census. In addition to creating a safety net, implementing a backup system addresses the common problem of the same hospitalists disproportionately filling in during times of crisis.

Although our group created a formal backup system starting January 2015, it is not comprehensive and deals only with high patient volumes occurring during the late evening and night hours. Hospitalists rotate through a schedule, taking a week of backup call for which no additional compensation is offered. Then, if they are actually called to come in, an hourly stipend is paid in addition to work RVUs generated. Implementing a backup system was not necessarily a popular idea. Nevertheless, the system has successfully remained in place. Triggering the system infrequently, having a clear set of criteria for when to activate backup, and providing additional compensation for the additional work are key factors in our system’s success.

When data from the 2016 SoHM report are compared with the 2014 SoHM report, the proportion of groups with formal backup systems actually decreases for both adults-only HMGs and HMGs serving both adults and children. For adult-only HMGs, there was a decline to 41.8% from 57.6%. For adult/pediatric HMGs, there was a decline to 47.4% from 58.8%. It also is notable that pediatric HMGs in particular are much less likely to have formal backup systems, only 27.8%, which has changed little since the last survey (28.8 % in 2014).

All in all, the reasons for the decline in backup systems are unclear. Possibly, the decrease is because of issues surrounding compensation, as approximately one-third of survey respondents with backup systems received no additional compensation. But in my view, it’s more likely that the reason for the decreased percentage of groups with backup systems has to do with differences in the particular set of HMGs that responded to the survey this year.

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists Play Key Role Developing Electronic Health Records

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

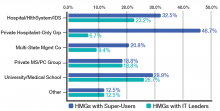

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.