User login

Stimulants for adult bipolar disorder?

Patients with bipolar disorder show an unpredictable range of responses to stimulants, from virtually no ill effects to emerging manic-like symptoms.1 Thus, although stimulants may be beneficial to some bipolar patients, there is a great deal of concern about using stimulants in this population. Even so, stimulants may be a rational adjunct for treating certain aspects of bipolar illness, particularly resistant depression, iatrogenic sedation, and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

To help you decide if and when your patient might be a candidate for stimulant therapy, this article:

- reviews the evidence on stimulants’ safety and tolerability for patients with bipolar disorder

- weighs potential benefits and risks of using stimulants in this population

- addresses stimulants’ possible adverse effects on illness course and from interactions with other psychotropics

- discusses treatment options based on the limited evidence and our clinical experience.

Limited support

We are aware that using stimulants to treat patients with bipolar disorder is not an uncommon clinical practice, but supportive evidence is limited (Table 1). In searching the literature, we found only 2 randomized controlled studies—Frye et al2 and Scheffer et al3—that addressed this practice. (One author of this review [TS] participated as a coinvestigator with Frye et al.2) Other evidence that suggests a role for stimulants in bipolar disorder comes from case reports, retrospective case series, and open-label studies.4-11

- “traditional” stimulants (including amphetamine-based compounds such as dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, and lisdexamfetamine) thought to affect the dopamine transporter, resulting in increased dopamine in nerve terminals

- the “novel” psychostimulant modafinil, thought to affect multiple neurotransmitter systems (dopamine, GABA, serotonin, histamine, and glutamate), although its mechanism of action is unclear.

Table 1

Clinical studies of stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder

| Stimulant(s) studied | Study design | Patients studied | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional stimulants | |||

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | Chart review, naturalistic12 | 16 adults (5 with comorbid ADHD, 11 with bipolar depression) | Improvements in depression, overall functioning, and ability to concentrate; sleep disturbance, irritability/agitation reported |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate or racemic mixture of AMPH salts | Chart review of sedation and depressive symptoms13 | 8 adults (BD II) | Improved clinical impression of bipolar illness; no manic switches, changes in cycling patterns, or substance abuse noted |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | 12-week open study, bipolar depression14 | 12 adults (10 BD I, 2 BD II) | Significant clinical improvements in depressive symptoms; no change in manic symptoms; anxiety, agitation, and hypomania reported |

| Multiple stimulants | Chart review, history of stimulants and bipolar illness course25 | 34 hospitalized adolescents | Prior stimulant treatment associated with earlier age of illness onset |

| Adjunctive mixed amphetamine salts | Randomized, placebo-controlled; comorbid BD and ADHD3 | 30 children with ADHD symptoms stabilized on divalproex sodium | Decrease in ADHD symptoms with adjunctive amphetamine treatment but not with divalproex sodium alone; 1 case of mania |

| Novel stimulant | |||

| Adjunctive modafinil | Case series15 | Mixed sample of depressed adults (4 unipolar, 3 bipolar) | Significant improvement in depressive symptoms |

| Adjunctive modafinil | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled2 | 85 adults with bipolar depression | Treatment group showed greater response and remission of depressive symptoms compared with placebo group; no difference in development of manic symptoms |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AMPH: amphetamine; BD: bipolar disorder; NOS: not otherwise specified | |||

Depression and iatrogenic sedation

Small, uncontrolled trials have reported some benefit and tolerability in bipolar disorder patients when stimulants are used to treat residual depressive symptoms or iatrogenic sedation associated with mood stabilizers.

Traditional stimulants. A retrospective chart review of 16 patients treated with adjunctive methylphenidate noted improved functioning, as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale. Some patients’ depressive symptoms and concentration also appeared to improve, but how these parameters were assessed is not clear. Some patients tolerated stimulants well, whereas others experienced irritability, agitation, and sleep disturbances.12

Another retrospective chart review described 8 patients with iatrogenic sedation or depression who received adjunctive methylphenidate, mean 20 to 40 mg/d, or a racemic mixture of amphetamine salts, mean 20 to 40 mg/d. Overall bipolar symptoms decreased in severity, as measured by Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores, but the authors did not directly measure sedation or depression. The stimulants were well-tolerated, with no evidence of stimulant-induced mania.13

In a 12-week open-label trial of methylphenidate in 14 patients with bipolar disorder, depressive symptoms improved as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Mean doses were 10 mg/d for the 3 patients who discontinued because of anxiety, agitation, or hypomania and 16.6 mg/d for those who completed the trial.14

Modafinil may have some efficacy in treating bipolar depression. In a case series of 7 depressed patients (4 unipolar and 3 bipolar), 5 patients showed a 50% decrease in HAM-D scores with adjunctive modafinil. Dosages ranged from 100 to 200 mg/d, although most patients took 200 mg/d. In this series, modafinil was added to a variety of treatments, including bupropion, nefazodone, paroxetine, venlafaxine, an unspecified tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), divalproex sodium, lamotrigine, lithium, electroconvulsive therapy, olanzapine, and gabapentin.15

The only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive modafinil for bipolar depression enrolled 85 patients with moderate or more severe depression. In this 6-week trial by Frye et al,2 41 patients received modafinil, 100 to 200 mg/d (mean dose 174.2 mg/d), and 44 received placebo.

Bipolar disorder plus ADHD

An estimated 10% to 21% of bipolar patients meet criteria for ADHD,16-19 although at times the line differentiating these 2 disorders is unclear. Co-occurring ADHD worsens the course of bipolar illness,20-22 and data from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial suggest that only 2% of dual-diagnosis patients are receiving treatment specifically for ADHD symptoms.23

Theoretically, overlapping symptoms such as talkativeness, distractibility, and physical activity remain relatively constant in ADHD but wax and wane with bipolar disorder’s manic and depressive phases. Recent evidence suggests, however, that many bipolar patients experience prodromal symptoms that may resemble ADHD, including cognitive impairment, distractibility, and increased psychomotor activity.24 In addition, medications used to treat bipolar disorder may impair cognitive function, making ADHD diagnosis difficult in this population.

We are not aware of any clinical trials that examined stimulants’ safety and efficacy in adult bipolar patients with co-occurring ADHD. One of the only studies to examine stimulant treatment of ADHD symptoms in a bipolar population was a retrospective chart review of 34 adolescents hospitalized with bipolar mania. An earlier age of bipolar illness onset was reported in adolescents who had been exposed to stimulants, whether or not they also had ADHD.25

Possible adverse events

Some bipolar disorder patients tolerate stimulants well, whereas others experience serious side effects, toxicities, and illness destabilization (Table 2). Because mood-stabilizer treatment may attenuate stimulants’ undesirable effects in bipolar disorder patients,26,27 be sure to use adequate dosing of a mood stabilizer if you determine a stimulant trial is warranted in your patient.

Destabilization. Stimulants can have a direct negative effect on mood; they can cause restlessness, irritability, anxiety, and mood lability. Some bipolar patients may be more sensitive to these adverse effects than others. Particularly concerning is the possibility of switching to mania or worsening of manic symptoms.28,29 Other potential destabilizing effects include:

- changing cycling patterns, such as inducing rapid cycling

- sleep disturbance because stimulants promote wakefulness.

If you are considering stimulant treatment for a bipolar disorder patient in whom substance abuse is a concern, modafinil or lisdexamfetamine may have a lower abuse potential compared with immediate-release psychostimulants. Lisdexamfetamine is metabolized in the GI tract and does not produce high d-amphetamine blood levels or cause reinforcing effects if injected or snorted.34

Table 2

Possible stimulant side effects, signs of toxicity, and contraindications

| Stimulant class | Possible side effects | Signs of toxicity/overdose | Contraindications/cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, confusion, tremor, tachycardia, hyperreflexia, hypertension, sweating, psychomotor agitation, seizure, arrhythmia, coma, psychosis | Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, Tourette’s syndrome/motor tics, history of seizure disorder, hypersensitivity to medication class |

| Novel (modafinil) | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, tremor, nausea, diarrhea, confusion | Cardiovascular disease, hepatic impairment, psychosis |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | |||

Drug-drug interactions

Polypharmacy is the rule in treating bipolar disorder, and stimulants can interact with many other psychotropics (Table 3).

Antidepressants. Never use traditional stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, as this combination may precipitate a hypertensive crisis. Coadministered stimulants also may decrease the metabolism of serotonergic agents—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—and cause side effects associated with increased serotonin neurotransmission, including serotonin syndrome.

Combining traditional stimulants with TCAs may increase TCA concentrations. When coadministered with bupropion, stimulants can increase the risk of seizures.

Modafinil is both an inducer and inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. Because it induces CYP3A4 and inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, modafinil interacts with many other psychopharmacologic agents:

- Its induction of CYP3A4 may increase the metabolism of commonly used medications such as carbamazepine, aripiprazole, and triazolam.

- Its inhibition of CYP2C19 may decrease the metabolism of many SSRIs, TCAs, diazepam, and clozapine, increasing these drugs’ effects and adverse events.

Possible stimulant interactions with other psychotropics

| Stimulant class | Psychotropic medication | Possible adverse effects |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis |

| CBZ | Reduced methylphenidate levels; abruptly stopping CBZ increases methylphenidate’s effect | |

| TCAs | Increased TCA concentration | |

| SSRIs, SNRIs | Possible decreased metabolism of antidepressants; potential for serotonin syndrome or NMS-like syndrome | |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics | Each may interfere with the other’s therapeutic action | |

| Novel (modafinil) | CBZ | Decreased modafinil efficacy; decreased CBZ levels |

| Triazolam | Decreased triazolam efficacy; increased effects of triazolam with modafinil discontinuation | |

| Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | Decreased modafinil clearance | |

| Citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of antidepressant | |

| MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis(?); not recommended | |

| Diazepam | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of diazepam | |

| TCAs | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of TCAs | |

| Clozapine | Increased clozapine concentration (case report) | |

| Aripiprazole | Decreased levels of aripiprazole | |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | ||

| CBZ: carbamazepine; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants | ||

Treatment considerations

Without evidence to support stimulants’ safety and efficacy in patients with bipolar disorder, we cannot make specific recommendations. We would, however, like to offer some general recommendations if you decide to use stimulants when treating patients with bipolar disorder (Table 4).

Carefully assess and—in many cases—reassess the patient’s symptoms to clarify the diagnosis. As mentioned, ADHD and bipolar disorder share many symptoms, particularly in the manic phase of bipolar illness. Overlapping symptoms include decreased ability to concentrate and focus, distractibility, hyperactivity and psychomotor agitation, racing thoughts, and impulsivity.

Substance abuse can negatively impact bipolar illness and present as clinical scenarios in which stimulants are used (such as treatment-resistant depression, impulsivity, somnolence, or fatigue).

Treat medical conditions such as thyroid disease, diabetes, and sleep apnea, which may worsen depression, cause somnolence and sedation, and present with symptoms similar to those of ADHD.

When possible, use lifestyle techniques to help patients manage the course of bipolar illness. Encourage good sleep hygiene, exercise, stable social rhythms, and limited use of alcohol and caffeine (both of which can impair sleep quality, which affects illness stability).

The next step. When you have explored all medication options and ruled out all other causes for the patient’s symptoms, stimulant treatment may be an appropriate next step. In these cases:

Encourage patients to participate in treatment, particularly in monitoring mood changes (as with life charts), symptoms associated with mood episodes, and emergence of side effects. When possible, involve family members in monitoring for adverse events.

Administration. Start stimulants only when bipolar illness is well-stabilized, especially regarding manic symptoms. We highly caution against using stimulants in patients with manic or hypomanic symptoms, including mixed states. We recommend not using stimulants in patients with:

- clinically significant insomnia or sleep fragmentation

- active suicidal ideation or psychotic symptoms, particularly if associated with manic symptoms.

Schedule frequent office visits when prescribing stimulants. At least initially, see patients every other week to assess for the emergence of adverse events.

Table 4

6 recommendations when using stimulants in bipolar disorder

| Carefully assess patient’s symptoms | Manic symptoms vs ADHD; medical conditions such as thyroid disorders, diabetes, or sleep apnea |

| Review possible iatrogenic causes of symptoms | Somnolence, decreased energy/fatigue, sedation, difficulty with concentration/focus |

| Engage patient in the therapeutic process | Discuss risks and benefits; monitor mood with life charts; enlist help of family, significant others when appropriate |

| Use caution in clinical scenarios that may herald adverse response to stimulants | Manic/hypomanic symptoms; sleep disturbances; psychosis; history of substance abuse |

| Administer stimulants with caution | Start low and go slow; always use stimulants in conjunction with a mood-stabilizing agent; be aware of possible interactions with patient’s other medications; schedule more frequent visits when starting stimulants |

| Monitor for adverse events associated with stimulant administration | Manic symptoms, changes in cycling patterns, sleep disturbances, substance abuse |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

- The Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Texas Department of State Health Services. www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/tmapover.shtm.

- The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane.org.

- Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, DextroStat

- Diazepam • Valium

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

- Lithium • various

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta, others

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Dr. Gonzalez reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products. He is a recipient of a T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards training fellowship sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Suppes receives grants/research support from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, JDS Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

1. Silberman EK, Reus VI, Jimerson DC, et al. Heterogeneity of amphetamine response in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138(10):1302-7.

2. Frye MA, Grunze H, Suppes T, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of adjunctive modafinil in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164(8):1242-9.

3. Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Rush AJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilization with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(1):58-64.

4. Meyers B. Treatment of imipramine-resistant depression and lithium-refractory mania through drug interactions. Am J Psychiatry 1978;135(11):1420-1.

5. Bannet J, Ebstein RP, Belmaker RH. Clinical aspects of the interaction of lithium and stimulants. Br J Psychiatry 1980;136:204.-

6. Drimmer EJ, Gitlin MJ, Gwirtsman HE. Desipramine and methylphenidate combination treatment for depression: case report. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140(2):241-2.

7. Fernandes PP, Petty F. Modafinil for remitted bipolar depression with hypersomnia. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37(12):1807-9.

8. Berigan TR. Augmentation with modafinil to achieve remission in depression: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3(1):32.-

9. Berigan TR. Modafinil treatment of excessive daytime sedation and fatigue associated with topiramate. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002;4(6):249-50.

10. Berigan T. Modafinil treatment of excessive sedation associated with divalproex sodium. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49(1):72-3.

11. Even C, Thuile J, Santos J, Bourgin P. Modafinil as an adjunctive treatment to sleep deprivation in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005;30(6):432-3.

12. Lydon E, El-Mallakh RS. Naturalistic long-term use of methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26(5):516-8.

13. Carlson PJ, Merlock MC, Suppes T. Adjunctive stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder: treatment of residual depression and sedation. Bipolar Disord 2004;6(5):416-20.

14. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

15. Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(5):378-81.

16. Wingo AP, Ghaemi SN. A systematic review of rates and diagnostic validity of comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(11):1776-84.

17. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

18. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

19. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, Ozcan S. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

20. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mennin D, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder: a familial subtype? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10):1378-87; discussion 1387-90.

21. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder in girls: further evidence for a familial subtype? J Affect Disord 2001;64(1):19-26.

22. Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT. The genetics of pediatriconset bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53(11):970-7.

23. Simon NM, Otto MW, Weiss RD, et al. Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and comorbid conditions: baseline data from STEP-BD. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(5):512-20.

24. Calabrese JR. Overview of patient care issues and treatment in bipolar spectrum and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(6):e18.-

25. DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, et al. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar Disord 2001;3(2):53-7.

26. Van Kammen DP, Murphy DL. Attenuation of the euphoriant and activating effects of d- and l-amphetamine by lithium carbonate treatment. Psychopharmacologia 1975;44(3):215-24.

27. Huey LY, Janowsky DS, Judd LL, et al. Effects of lithium carbonate on methylphenidate-induced mood, behavior, and cognitive processes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;73(2):161-4.

28. Gerner RH, Post RM, Bunney WE, Jr. A dopaminergic mechanism in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1976;133(10):1177-80.

29. Koehler-Troy C, Strober M, Malenbaum R. Methylphenidateinduced mania in a prepubertal child. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47(11):566-7.

30. Brady KT, Sonne SC. The relationship between substance abuse and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 3):19-24.

31. Sonne SC, Brady KT. Substance abuse and bipolar comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999;22(3):609-27,ix.

32. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990;264(19):2511-8.

33. Estroff TW, Dackis CA, Gold MS, Pottash AL. Drug abuse and bipolar disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1985-1986;15(1):37-40.

34. Faraone SV. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: the first longacting prodrug stimulant treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008;9(9):1565-74.

Patients with bipolar disorder show an unpredictable range of responses to stimulants, from virtually no ill effects to emerging manic-like symptoms.1 Thus, although stimulants may be beneficial to some bipolar patients, there is a great deal of concern about using stimulants in this population. Even so, stimulants may be a rational adjunct for treating certain aspects of bipolar illness, particularly resistant depression, iatrogenic sedation, and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

To help you decide if and when your patient might be a candidate for stimulant therapy, this article:

- reviews the evidence on stimulants’ safety and tolerability for patients with bipolar disorder

- weighs potential benefits and risks of using stimulants in this population

- addresses stimulants’ possible adverse effects on illness course and from interactions with other psychotropics

- discusses treatment options based on the limited evidence and our clinical experience.

Limited support

We are aware that using stimulants to treat patients with bipolar disorder is not an uncommon clinical practice, but supportive evidence is limited (Table 1). In searching the literature, we found only 2 randomized controlled studies—Frye et al2 and Scheffer et al3—that addressed this practice. (One author of this review [TS] participated as a coinvestigator with Frye et al.2) Other evidence that suggests a role for stimulants in bipolar disorder comes from case reports, retrospective case series, and open-label studies.4-11

- “traditional” stimulants (including amphetamine-based compounds such as dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, and lisdexamfetamine) thought to affect the dopamine transporter, resulting in increased dopamine in nerve terminals

- the “novel” psychostimulant modafinil, thought to affect multiple neurotransmitter systems (dopamine, GABA, serotonin, histamine, and glutamate), although its mechanism of action is unclear.

Table 1

Clinical studies of stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder

| Stimulant(s) studied | Study design | Patients studied | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional stimulants | |||

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | Chart review, naturalistic12 | 16 adults (5 with comorbid ADHD, 11 with bipolar depression) | Improvements in depression, overall functioning, and ability to concentrate; sleep disturbance, irritability/agitation reported |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate or racemic mixture of AMPH salts | Chart review of sedation and depressive symptoms13 | 8 adults (BD II) | Improved clinical impression of bipolar illness; no manic switches, changes in cycling patterns, or substance abuse noted |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | 12-week open study, bipolar depression14 | 12 adults (10 BD I, 2 BD II) | Significant clinical improvements in depressive symptoms; no change in manic symptoms; anxiety, agitation, and hypomania reported |

| Multiple stimulants | Chart review, history of stimulants and bipolar illness course25 | 34 hospitalized adolescents | Prior stimulant treatment associated with earlier age of illness onset |

| Adjunctive mixed amphetamine salts | Randomized, placebo-controlled; comorbid BD and ADHD3 | 30 children with ADHD symptoms stabilized on divalproex sodium | Decrease in ADHD symptoms with adjunctive amphetamine treatment but not with divalproex sodium alone; 1 case of mania |

| Novel stimulant | |||

| Adjunctive modafinil | Case series15 | Mixed sample of depressed adults (4 unipolar, 3 bipolar) | Significant improvement in depressive symptoms |

| Adjunctive modafinil | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled2 | 85 adults with bipolar depression | Treatment group showed greater response and remission of depressive symptoms compared with placebo group; no difference in development of manic symptoms |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AMPH: amphetamine; BD: bipolar disorder; NOS: not otherwise specified | |||

Depression and iatrogenic sedation

Small, uncontrolled trials have reported some benefit and tolerability in bipolar disorder patients when stimulants are used to treat residual depressive symptoms or iatrogenic sedation associated with mood stabilizers.

Traditional stimulants. A retrospective chart review of 16 patients treated with adjunctive methylphenidate noted improved functioning, as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale. Some patients’ depressive symptoms and concentration also appeared to improve, but how these parameters were assessed is not clear. Some patients tolerated stimulants well, whereas others experienced irritability, agitation, and sleep disturbances.12

Another retrospective chart review described 8 patients with iatrogenic sedation or depression who received adjunctive methylphenidate, mean 20 to 40 mg/d, or a racemic mixture of amphetamine salts, mean 20 to 40 mg/d. Overall bipolar symptoms decreased in severity, as measured by Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores, but the authors did not directly measure sedation or depression. The stimulants were well-tolerated, with no evidence of stimulant-induced mania.13

In a 12-week open-label trial of methylphenidate in 14 patients with bipolar disorder, depressive symptoms improved as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Mean doses were 10 mg/d for the 3 patients who discontinued because of anxiety, agitation, or hypomania and 16.6 mg/d for those who completed the trial.14

Modafinil may have some efficacy in treating bipolar depression. In a case series of 7 depressed patients (4 unipolar and 3 bipolar), 5 patients showed a 50% decrease in HAM-D scores with adjunctive modafinil. Dosages ranged from 100 to 200 mg/d, although most patients took 200 mg/d. In this series, modafinil was added to a variety of treatments, including bupropion, nefazodone, paroxetine, venlafaxine, an unspecified tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), divalproex sodium, lamotrigine, lithium, electroconvulsive therapy, olanzapine, and gabapentin.15

The only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive modafinil for bipolar depression enrolled 85 patients with moderate or more severe depression. In this 6-week trial by Frye et al,2 41 patients received modafinil, 100 to 200 mg/d (mean dose 174.2 mg/d), and 44 received placebo.

Bipolar disorder plus ADHD

An estimated 10% to 21% of bipolar patients meet criteria for ADHD,16-19 although at times the line differentiating these 2 disorders is unclear. Co-occurring ADHD worsens the course of bipolar illness,20-22 and data from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial suggest that only 2% of dual-diagnosis patients are receiving treatment specifically for ADHD symptoms.23

Theoretically, overlapping symptoms such as talkativeness, distractibility, and physical activity remain relatively constant in ADHD but wax and wane with bipolar disorder’s manic and depressive phases. Recent evidence suggests, however, that many bipolar patients experience prodromal symptoms that may resemble ADHD, including cognitive impairment, distractibility, and increased psychomotor activity.24 In addition, medications used to treat bipolar disorder may impair cognitive function, making ADHD diagnosis difficult in this population.

We are not aware of any clinical trials that examined stimulants’ safety and efficacy in adult bipolar patients with co-occurring ADHD. One of the only studies to examine stimulant treatment of ADHD symptoms in a bipolar population was a retrospective chart review of 34 adolescents hospitalized with bipolar mania. An earlier age of bipolar illness onset was reported in adolescents who had been exposed to stimulants, whether or not they also had ADHD.25

Possible adverse events

Some bipolar disorder patients tolerate stimulants well, whereas others experience serious side effects, toxicities, and illness destabilization (Table 2). Because mood-stabilizer treatment may attenuate stimulants’ undesirable effects in bipolar disorder patients,26,27 be sure to use adequate dosing of a mood stabilizer if you determine a stimulant trial is warranted in your patient.

Destabilization. Stimulants can have a direct negative effect on mood; they can cause restlessness, irritability, anxiety, and mood lability. Some bipolar patients may be more sensitive to these adverse effects than others. Particularly concerning is the possibility of switching to mania or worsening of manic symptoms.28,29 Other potential destabilizing effects include:

- changing cycling patterns, such as inducing rapid cycling

- sleep disturbance because stimulants promote wakefulness.

If you are considering stimulant treatment for a bipolar disorder patient in whom substance abuse is a concern, modafinil or lisdexamfetamine may have a lower abuse potential compared with immediate-release psychostimulants. Lisdexamfetamine is metabolized in the GI tract and does not produce high d-amphetamine blood levels or cause reinforcing effects if injected or snorted.34

Table 2

Possible stimulant side effects, signs of toxicity, and contraindications

| Stimulant class | Possible side effects | Signs of toxicity/overdose | Contraindications/cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, confusion, tremor, tachycardia, hyperreflexia, hypertension, sweating, psychomotor agitation, seizure, arrhythmia, coma, psychosis | Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, Tourette’s syndrome/motor tics, history of seizure disorder, hypersensitivity to medication class |

| Novel (modafinil) | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, tremor, nausea, diarrhea, confusion | Cardiovascular disease, hepatic impairment, psychosis |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | |||

Drug-drug interactions

Polypharmacy is the rule in treating bipolar disorder, and stimulants can interact with many other psychotropics (Table 3).

Antidepressants. Never use traditional stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, as this combination may precipitate a hypertensive crisis. Coadministered stimulants also may decrease the metabolism of serotonergic agents—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—and cause side effects associated with increased serotonin neurotransmission, including serotonin syndrome.

Combining traditional stimulants with TCAs may increase TCA concentrations. When coadministered with bupropion, stimulants can increase the risk of seizures.

Modafinil is both an inducer and inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. Because it induces CYP3A4 and inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, modafinil interacts with many other psychopharmacologic agents:

- Its induction of CYP3A4 may increase the metabolism of commonly used medications such as carbamazepine, aripiprazole, and triazolam.

- Its inhibition of CYP2C19 may decrease the metabolism of many SSRIs, TCAs, diazepam, and clozapine, increasing these drugs’ effects and adverse events.

Possible stimulant interactions with other psychotropics

| Stimulant class | Psychotropic medication | Possible adverse effects |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis |

| CBZ | Reduced methylphenidate levels; abruptly stopping CBZ increases methylphenidate’s effect | |

| TCAs | Increased TCA concentration | |

| SSRIs, SNRIs | Possible decreased metabolism of antidepressants; potential for serotonin syndrome or NMS-like syndrome | |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics | Each may interfere with the other’s therapeutic action | |

| Novel (modafinil) | CBZ | Decreased modafinil efficacy; decreased CBZ levels |

| Triazolam | Decreased triazolam efficacy; increased effects of triazolam with modafinil discontinuation | |

| Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | Decreased modafinil clearance | |

| Citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of antidepressant | |

| MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis(?); not recommended | |

| Diazepam | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of diazepam | |

| TCAs | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of TCAs | |

| Clozapine | Increased clozapine concentration (case report) | |

| Aripiprazole | Decreased levels of aripiprazole | |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | ||

| CBZ: carbamazepine; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants | ||

Treatment considerations

Without evidence to support stimulants’ safety and efficacy in patients with bipolar disorder, we cannot make specific recommendations. We would, however, like to offer some general recommendations if you decide to use stimulants when treating patients with bipolar disorder (Table 4).

Carefully assess and—in many cases—reassess the patient’s symptoms to clarify the diagnosis. As mentioned, ADHD and bipolar disorder share many symptoms, particularly in the manic phase of bipolar illness. Overlapping symptoms include decreased ability to concentrate and focus, distractibility, hyperactivity and psychomotor agitation, racing thoughts, and impulsivity.

Substance abuse can negatively impact bipolar illness and present as clinical scenarios in which stimulants are used (such as treatment-resistant depression, impulsivity, somnolence, or fatigue).

Treat medical conditions such as thyroid disease, diabetes, and sleep apnea, which may worsen depression, cause somnolence and sedation, and present with symptoms similar to those of ADHD.

When possible, use lifestyle techniques to help patients manage the course of bipolar illness. Encourage good sleep hygiene, exercise, stable social rhythms, and limited use of alcohol and caffeine (both of which can impair sleep quality, which affects illness stability).

The next step. When you have explored all medication options and ruled out all other causes for the patient’s symptoms, stimulant treatment may be an appropriate next step. In these cases:

Encourage patients to participate in treatment, particularly in monitoring mood changes (as with life charts), symptoms associated with mood episodes, and emergence of side effects. When possible, involve family members in monitoring for adverse events.

Administration. Start stimulants only when bipolar illness is well-stabilized, especially regarding manic symptoms. We highly caution against using stimulants in patients with manic or hypomanic symptoms, including mixed states. We recommend not using stimulants in patients with:

- clinically significant insomnia or sleep fragmentation

- active suicidal ideation or psychotic symptoms, particularly if associated with manic symptoms.

Schedule frequent office visits when prescribing stimulants. At least initially, see patients every other week to assess for the emergence of adverse events.

Table 4

6 recommendations when using stimulants in bipolar disorder

| Carefully assess patient’s symptoms | Manic symptoms vs ADHD; medical conditions such as thyroid disorders, diabetes, or sleep apnea |

| Review possible iatrogenic causes of symptoms | Somnolence, decreased energy/fatigue, sedation, difficulty with concentration/focus |

| Engage patient in the therapeutic process | Discuss risks and benefits; monitor mood with life charts; enlist help of family, significant others when appropriate |

| Use caution in clinical scenarios that may herald adverse response to stimulants | Manic/hypomanic symptoms; sleep disturbances; psychosis; history of substance abuse |

| Administer stimulants with caution | Start low and go slow; always use stimulants in conjunction with a mood-stabilizing agent; be aware of possible interactions with patient’s other medications; schedule more frequent visits when starting stimulants |

| Monitor for adverse events associated with stimulant administration | Manic symptoms, changes in cycling patterns, sleep disturbances, substance abuse |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

- The Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Texas Department of State Health Services. www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/tmapover.shtm.

- The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane.org.

- Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, DextroStat

- Diazepam • Valium

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

- Lithium • various

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta, others

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Dr. Gonzalez reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products. He is a recipient of a T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards training fellowship sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Suppes receives grants/research support from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, JDS Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

Patients with bipolar disorder show an unpredictable range of responses to stimulants, from virtually no ill effects to emerging manic-like symptoms.1 Thus, although stimulants may be beneficial to some bipolar patients, there is a great deal of concern about using stimulants in this population. Even so, stimulants may be a rational adjunct for treating certain aspects of bipolar illness, particularly resistant depression, iatrogenic sedation, and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

To help you decide if and when your patient might be a candidate for stimulant therapy, this article:

- reviews the evidence on stimulants’ safety and tolerability for patients with bipolar disorder

- weighs potential benefits and risks of using stimulants in this population

- addresses stimulants’ possible adverse effects on illness course and from interactions with other psychotropics

- discusses treatment options based on the limited evidence and our clinical experience.

Limited support

We are aware that using stimulants to treat patients with bipolar disorder is not an uncommon clinical practice, but supportive evidence is limited (Table 1). In searching the literature, we found only 2 randomized controlled studies—Frye et al2 and Scheffer et al3—that addressed this practice. (One author of this review [TS] participated as a coinvestigator with Frye et al.2) Other evidence that suggests a role for stimulants in bipolar disorder comes from case reports, retrospective case series, and open-label studies.4-11

- “traditional” stimulants (including amphetamine-based compounds such as dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, and lisdexamfetamine) thought to affect the dopamine transporter, resulting in increased dopamine in nerve terminals

- the “novel” psychostimulant modafinil, thought to affect multiple neurotransmitter systems (dopamine, GABA, serotonin, histamine, and glutamate), although its mechanism of action is unclear.

Table 1

Clinical studies of stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder

| Stimulant(s) studied | Study design | Patients studied | Clinical outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional stimulants | |||

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | Chart review, naturalistic12 | 16 adults (5 with comorbid ADHD, 11 with bipolar depression) | Improvements in depression, overall functioning, and ability to concentrate; sleep disturbance, irritability/agitation reported |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate or racemic mixture of AMPH salts | Chart review of sedation and depressive symptoms13 | 8 adults (BD II) | Improved clinical impression of bipolar illness; no manic switches, changes in cycling patterns, or substance abuse noted |

| Adjunctive methylphenidate | 12-week open study, bipolar depression14 | 12 adults (10 BD I, 2 BD II) | Significant clinical improvements in depressive symptoms; no change in manic symptoms; anxiety, agitation, and hypomania reported |

| Multiple stimulants | Chart review, history of stimulants and bipolar illness course25 | 34 hospitalized adolescents | Prior stimulant treatment associated with earlier age of illness onset |

| Adjunctive mixed amphetamine salts | Randomized, placebo-controlled; comorbid BD and ADHD3 | 30 children with ADHD symptoms stabilized on divalproex sodium | Decrease in ADHD symptoms with adjunctive amphetamine treatment but not with divalproex sodium alone; 1 case of mania |

| Novel stimulant | |||

| Adjunctive modafinil | Case series15 | Mixed sample of depressed adults (4 unipolar, 3 bipolar) | Significant improvement in depressive symptoms |

| Adjunctive modafinil | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled2 | 85 adults with bipolar depression | Treatment group showed greater response and remission of depressive symptoms compared with placebo group; no difference in development of manic symptoms |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AMPH: amphetamine; BD: bipolar disorder; NOS: not otherwise specified | |||

Depression and iatrogenic sedation

Small, uncontrolled trials have reported some benefit and tolerability in bipolar disorder patients when stimulants are used to treat residual depressive symptoms or iatrogenic sedation associated with mood stabilizers.

Traditional stimulants. A retrospective chart review of 16 patients treated with adjunctive methylphenidate noted improved functioning, as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale. Some patients’ depressive symptoms and concentration also appeared to improve, but how these parameters were assessed is not clear. Some patients tolerated stimulants well, whereas others experienced irritability, agitation, and sleep disturbances.12

Another retrospective chart review described 8 patients with iatrogenic sedation or depression who received adjunctive methylphenidate, mean 20 to 40 mg/d, or a racemic mixture of amphetamine salts, mean 20 to 40 mg/d. Overall bipolar symptoms decreased in severity, as measured by Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores, but the authors did not directly measure sedation or depression. The stimulants were well-tolerated, with no evidence of stimulant-induced mania.13

In a 12-week open-label trial of methylphenidate in 14 patients with bipolar disorder, depressive symptoms improved as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Mean doses were 10 mg/d for the 3 patients who discontinued because of anxiety, agitation, or hypomania and 16.6 mg/d for those who completed the trial.14

Modafinil may have some efficacy in treating bipolar depression. In a case series of 7 depressed patients (4 unipolar and 3 bipolar), 5 patients showed a 50% decrease in HAM-D scores with adjunctive modafinil. Dosages ranged from 100 to 200 mg/d, although most patients took 200 mg/d. In this series, modafinil was added to a variety of treatments, including bupropion, nefazodone, paroxetine, venlafaxine, an unspecified tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), divalproex sodium, lamotrigine, lithium, electroconvulsive therapy, olanzapine, and gabapentin.15

The only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive modafinil for bipolar depression enrolled 85 patients with moderate or more severe depression. In this 6-week trial by Frye et al,2 41 patients received modafinil, 100 to 200 mg/d (mean dose 174.2 mg/d), and 44 received placebo.

Bipolar disorder plus ADHD

An estimated 10% to 21% of bipolar patients meet criteria for ADHD,16-19 although at times the line differentiating these 2 disorders is unclear. Co-occurring ADHD worsens the course of bipolar illness,20-22 and data from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) trial suggest that only 2% of dual-diagnosis patients are receiving treatment specifically for ADHD symptoms.23

Theoretically, overlapping symptoms such as talkativeness, distractibility, and physical activity remain relatively constant in ADHD but wax and wane with bipolar disorder’s manic and depressive phases. Recent evidence suggests, however, that many bipolar patients experience prodromal symptoms that may resemble ADHD, including cognitive impairment, distractibility, and increased psychomotor activity.24 In addition, medications used to treat bipolar disorder may impair cognitive function, making ADHD diagnosis difficult in this population.

We are not aware of any clinical trials that examined stimulants’ safety and efficacy in adult bipolar patients with co-occurring ADHD. One of the only studies to examine stimulant treatment of ADHD symptoms in a bipolar population was a retrospective chart review of 34 adolescents hospitalized with bipolar mania. An earlier age of bipolar illness onset was reported in adolescents who had been exposed to stimulants, whether or not they also had ADHD.25

Possible adverse events

Some bipolar disorder patients tolerate stimulants well, whereas others experience serious side effects, toxicities, and illness destabilization (Table 2). Because mood-stabilizer treatment may attenuate stimulants’ undesirable effects in bipolar disorder patients,26,27 be sure to use adequate dosing of a mood stabilizer if you determine a stimulant trial is warranted in your patient.

Destabilization. Stimulants can have a direct negative effect on mood; they can cause restlessness, irritability, anxiety, and mood lability. Some bipolar patients may be more sensitive to these adverse effects than others. Particularly concerning is the possibility of switching to mania or worsening of manic symptoms.28,29 Other potential destabilizing effects include:

- changing cycling patterns, such as inducing rapid cycling

- sleep disturbance because stimulants promote wakefulness.

If you are considering stimulant treatment for a bipolar disorder patient in whom substance abuse is a concern, modafinil or lisdexamfetamine may have a lower abuse potential compared with immediate-release psychostimulants. Lisdexamfetamine is metabolized in the GI tract and does not produce high d-amphetamine blood levels or cause reinforcing effects if injected or snorted.34

Table 2

Possible stimulant side effects, signs of toxicity, and contraindications

| Stimulant class | Possible side effects | Signs of toxicity/overdose | Contraindications/cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, confusion, tremor, tachycardia, hyperreflexia, hypertension, sweating, psychomotor agitation, seizure, arrhythmia, coma, psychosis | Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma, Tourette’s syndrome/motor tics, history of seizure disorder, hypersensitivity to medication class |

| Novel (modafinil) | Restlessness, insomnia, mood lability, anxiety | Agitation, tremor, nausea, diarrhea, confusion | Cardiovascular disease, hepatic impairment, psychosis |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | |||

Drug-drug interactions

Polypharmacy is the rule in treating bipolar disorder, and stimulants can interact with many other psychotropics (Table 3).

Antidepressants. Never use traditional stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, as this combination may precipitate a hypertensive crisis. Coadministered stimulants also may decrease the metabolism of serotonergic agents—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—and cause side effects associated with increased serotonin neurotransmission, including serotonin syndrome.

Combining traditional stimulants with TCAs may increase TCA concentrations. When coadministered with bupropion, stimulants can increase the risk of seizures.

Modafinil is both an inducer and inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. Because it induces CYP3A4 and inhibits CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, modafinil interacts with many other psychopharmacologic agents:

- Its induction of CYP3A4 may increase the metabolism of commonly used medications such as carbamazepine, aripiprazole, and triazolam.

- Its inhibition of CYP2C19 may decrease the metabolism of many SSRIs, TCAs, diazepam, and clozapine, increasing these drugs’ effects and adverse events.

Possible stimulant interactions with other psychotropics

| Stimulant class | Psychotropic medication | Possible adverse effects |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional (amphetamine mixtures, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate)* | MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis |

| CBZ | Reduced methylphenidate levels; abruptly stopping CBZ increases methylphenidate’s effect | |

| TCAs | Increased TCA concentration | |

| SSRIs, SNRIs | Possible decreased metabolism of antidepressants; potential for serotonin syndrome or NMS-like syndrome | |

| Typical and atypical antipsychotics | Each may interfere with the other’s therapeutic action | |

| Novel (modafinil) | CBZ | Decreased modafinil efficacy; decreased CBZ levels |

| Triazolam | Decreased triazolam efficacy; increased effects of triazolam with modafinil discontinuation | |

| Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine | Decreased modafinil clearance | |

| Citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of antidepressant | |

| MAOIs | Hypertensive crisis(?); not recommended | |

| Diazepam | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of diazepam | |

| TCAs | Prolonged elimination and increased levels of TCAs | |

| Clozapine | Increased clozapine concentration (case report) | |

| Aripiprazole | Decreased levels of aripiprazole | |

| * Amphetamines and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Adderall XR); dexmethylphenidate (Focalin, Focalin XR), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, DextroStat); lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse); methylphenidate (Concerta, Daytrana, Metadate CD, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR) | ||

| CBZ: carbamazepine; MAOIs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants | ||

Treatment considerations

Without evidence to support stimulants’ safety and efficacy in patients with bipolar disorder, we cannot make specific recommendations. We would, however, like to offer some general recommendations if you decide to use stimulants when treating patients with bipolar disorder (Table 4).

Carefully assess and—in many cases—reassess the patient’s symptoms to clarify the diagnosis. As mentioned, ADHD and bipolar disorder share many symptoms, particularly in the manic phase of bipolar illness. Overlapping symptoms include decreased ability to concentrate and focus, distractibility, hyperactivity and psychomotor agitation, racing thoughts, and impulsivity.

Substance abuse can negatively impact bipolar illness and present as clinical scenarios in which stimulants are used (such as treatment-resistant depression, impulsivity, somnolence, or fatigue).

Treat medical conditions such as thyroid disease, diabetes, and sleep apnea, which may worsen depression, cause somnolence and sedation, and present with symptoms similar to those of ADHD.

When possible, use lifestyle techniques to help patients manage the course of bipolar illness. Encourage good sleep hygiene, exercise, stable social rhythms, and limited use of alcohol and caffeine (both of which can impair sleep quality, which affects illness stability).

The next step. When you have explored all medication options and ruled out all other causes for the patient’s symptoms, stimulant treatment may be an appropriate next step. In these cases:

Encourage patients to participate in treatment, particularly in monitoring mood changes (as with life charts), symptoms associated with mood episodes, and emergence of side effects. When possible, involve family members in monitoring for adverse events.

Administration. Start stimulants only when bipolar illness is well-stabilized, especially regarding manic symptoms. We highly caution against using stimulants in patients with manic or hypomanic symptoms, including mixed states. We recommend not using stimulants in patients with:

- clinically significant insomnia or sleep fragmentation

- active suicidal ideation or psychotic symptoms, particularly if associated with manic symptoms.

Schedule frequent office visits when prescribing stimulants. At least initially, see patients every other week to assess for the emergence of adverse events.

Table 4

6 recommendations when using stimulants in bipolar disorder

| Carefully assess patient’s symptoms | Manic symptoms vs ADHD; medical conditions such as thyroid disorders, diabetes, or sleep apnea |

| Review possible iatrogenic causes of symptoms | Somnolence, decreased energy/fatigue, sedation, difficulty with concentration/focus |

| Engage patient in the therapeutic process | Discuss risks and benefits; monitor mood with life charts; enlist help of family, significant others when appropriate |

| Use caution in clinical scenarios that may herald adverse response to stimulants | Manic/hypomanic symptoms; sleep disturbances; psychosis; history of substance abuse |

| Administer stimulants with caution | Start low and go slow; always use stimulants in conjunction with a mood-stabilizing agent; be aware of possible interactions with patient’s other medications; schedule more frequent visits when starting stimulants |

| Monitor for adverse events associated with stimulant administration | Manic symptoms, changes in cycling patterns, sleep disturbances, substance abuse |

| ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

- The Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Texas Department of State Health Services. www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/tmapover.shtm.

- The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane.org.

- Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

- Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, DextroStat

- Diazepam • Valium

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

- Lithium • various

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta, others

- Modafinil • Provigil

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Triazolam • Halcion

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Dr. Gonzalez reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in the article or with manufacturers of competing products. He is a recipient of a T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards training fellowship sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Suppes receives grants/research support from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, JDS Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

1. Silberman EK, Reus VI, Jimerson DC, et al. Heterogeneity of amphetamine response in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138(10):1302-7.

2. Frye MA, Grunze H, Suppes T, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of adjunctive modafinil in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164(8):1242-9.

3. Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Rush AJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilization with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(1):58-64.

4. Meyers B. Treatment of imipramine-resistant depression and lithium-refractory mania through drug interactions. Am J Psychiatry 1978;135(11):1420-1.

5. Bannet J, Ebstein RP, Belmaker RH. Clinical aspects of the interaction of lithium and stimulants. Br J Psychiatry 1980;136:204.-

6. Drimmer EJ, Gitlin MJ, Gwirtsman HE. Desipramine and methylphenidate combination treatment for depression: case report. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140(2):241-2.

7. Fernandes PP, Petty F. Modafinil for remitted bipolar depression with hypersomnia. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37(12):1807-9.

8. Berigan TR. Augmentation with modafinil to achieve remission in depression: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3(1):32.-

9. Berigan TR. Modafinil treatment of excessive daytime sedation and fatigue associated with topiramate. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002;4(6):249-50.

10. Berigan T. Modafinil treatment of excessive sedation associated with divalproex sodium. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49(1):72-3.

11. Even C, Thuile J, Santos J, Bourgin P. Modafinil as an adjunctive treatment to sleep deprivation in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005;30(6):432-3.

12. Lydon E, El-Mallakh RS. Naturalistic long-term use of methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26(5):516-8.

13. Carlson PJ, Merlock MC, Suppes T. Adjunctive stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder: treatment of residual depression and sedation. Bipolar Disord 2004;6(5):416-20.

14. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

15. Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(5):378-81.

16. Wingo AP, Ghaemi SN. A systematic review of rates and diagnostic validity of comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(11):1776-84.

17. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

18. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

19. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, Ozcan S. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

20. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mennin D, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder: a familial subtype? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10):1378-87; discussion 1387-90.

21. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder in girls: further evidence for a familial subtype? J Affect Disord 2001;64(1):19-26.

22. Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT. The genetics of pediatriconset bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53(11):970-7.

23. Simon NM, Otto MW, Weiss RD, et al. Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and comorbid conditions: baseline data from STEP-BD. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(5):512-20.

24. Calabrese JR. Overview of patient care issues and treatment in bipolar spectrum and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(6):e18.-

25. DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, et al. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar Disord 2001;3(2):53-7.

26. Van Kammen DP, Murphy DL. Attenuation of the euphoriant and activating effects of d- and l-amphetamine by lithium carbonate treatment. Psychopharmacologia 1975;44(3):215-24.

27. Huey LY, Janowsky DS, Judd LL, et al. Effects of lithium carbonate on methylphenidate-induced mood, behavior, and cognitive processes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;73(2):161-4.

28. Gerner RH, Post RM, Bunney WE, Jr. A dopaminergic mechanism in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1976;133(10):1177-80.

29. Koehler-Troy C, Strober M, Malenbaum R. Methylphenidateinduced mania in a prepubertal child. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47(11):566-7.

30. Brady KT, Sonne SC. The relationship between substance abuse and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 3):19-24.

31. Sonne SC, Brady KT. Substance abuse and bipolar comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999;22(3):609-27,ix.

32. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990;264(19):2511-8.

33. Estroff TW, Dackis CA, Gold MS, Pottash AL. Drug abuse and bipolar disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1985-1986;15(1):37-40.

34. Faraone SV. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: the first longacting prodrug stimulant treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008;9(9):1565-74.

1. Silberman EK, Reus VI, Jimerson DC, et al. Heterogeneity of amphetamine response in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138(10):1302-7.

2. Frye MA, Grunze H, Suppes T, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of adjunctive modafinil in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164(8):1242-9.

3. Scheffer RE, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Rush AJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mixed amphetamine salts for symptoms of comorbid ADHD in pediatric bipolar disorder after mood stabilization with divalproex sodium. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(1):58-64.

4. Meyers B. Treatment of imipramine-resistant depression and lithium-refractory mania through drug interactions. Am J Psychiatry 1978;135(11):1420-1.

5. Bannet J, Ebstein RP, Belmaker RH. Clinical aspects of the interaction of lithium and stimulants. Br J Psychiatry 1980;136:204.-

6. Drimmer EJ, Gitlin MJ, Gwirtsman HE. Desipramine and methylphenidate combination treatment for depression: case report. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140(2):241-2.

7. Fernandes PP, Petty F. Modafinil for remitted bipolar depression with hypersomnia. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37(12):1807-9.

8. Berigan TR. Augmentation with modafinil to achieve remission in depression: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3(1):32.-

9. Berigan TR. Modafinil treatment of excessive daytime sedation and fatigue associated with topiramate. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002;4(6):249-50.

10. Berigan T. Modafinil treatment of excessive sedation associated with divalproex sodium. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49(1):72-3.

11. Even C, Thuile J, Santos J, Bourgin P. Modafinil as an adjunctive treatment to sleep deprivation in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005;30(6):432-3.

12. Lydon E, El-Mallakh RS. Naturalistic long-term use of methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26(5):516-8.

13. Carlson PJ, Merlock MC, Suppes T. Adjunctive stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder: treatment of residual depression and sedation. Bipolar Disord 2004;6(5):416-20.

14. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2000;2(1):56-9.

15. Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(5):378-81.

16. Wingo AP, Ghaemi SN. A systematic review of rates and diagnostic validity of comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(11):1776-84.

17. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163(4):716-23.

18. Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1467-73.

19. Tamam L, Tuglu C, Karatas G, Ozcan S. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with bipolar I disorder in remission: preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;60(4):480-5.

20. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mennin D, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder: a familial subtype? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10):1378-87; discussion 1387-90.

21. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with bipolar disorder in girls: further evidence for a familial subtype? J Affect Disord 2001;64(1):19-26.

22. Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT. The genetics of pediatriconset bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53(11):970-7.

23. Simon NM, Otto MW, Weiss RD, et al. Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and comorbid conditions: baseline data from STEP-BD. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(5):512-20.

24. Calabrese JR. Overview of patient care issues and treatment in bipolar spectrum and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(6):e18.-

25. DelBello MP, Soutullo CA, Hendricks W, et al. Prior stimulant treatment in adolescents with bipolar disorder: association with age at onset. Bipolar Disord 2001;3(2):53-7.

26. Van Kammen DP, Murphy DL. Attenuation of the euphoriant and activating effects of d- and l-amphetamine by lithium carbonate treatment. Psychopharmacologia 1975;44(3):215-24.

27. Huey LY, Janowsky DS, Judd LL, et al. Effects of lithium carbonate on methylphenidate-induced mood, behavior, and cognitive processes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;73(2):161-4.

28. Gerner RH, Post RM, Bunney WE, Jr. A dopaminergic mechanism in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1976;133(10):1177-80.

29. Koehler-Troy C, Strober M, Malenbaum R. Methylphenidateinduced mania in a prepubertal child. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47(11):566-7.

30. Brady KT, Sonne SC. The relationship between substance abuse and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 3):19-24.

31. Sonne SC, Brady KT. Substance abuse and bipolar comorbidity. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999;22(3):609-27,ix.

32. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990;264(19):2511-8.

33. Estroff TW, Dackis CA, Gold MS, Pottash AL. Drug abuse and bipolar disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1985-1986;15(1):37-40.

34. Faraone SV. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: the first longacting prodrug stimulant treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008;9(9):1565-74.

Bipolar treatment update: Evidence is driving change in mania, depression algorithms

Many well-controlled trials in the past 4 years have evaluated new medications for treating bipolar disorder. It’s time to build a consensus on how this data may apply to clinical practice.

This year, our group will re-examine the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) treatment algorithms for bipolar I disorder.

What makes TMAP unique? It is the first project to evaluate treatment algorithm use in community mental health settings for patients with a history of mania (see Box).1-5 Severely, persistently ill outpatients such as these are seldom included in research but are frequently seen in clinical practice.

To preview for psychiatrists the changes expected in 2004, this article describes the goals of TMAP and the controlled study on which the medication algorithms are based. We review the medication algorithms of 2000 as a starting point and present the evidence that is changing clinical practice.

Guiding principles of TMAP

A treatment algorithm is no substitute for clinical judgment; rather, medication guidelines and algorithms are guideposts to help the clinician and patient collaboratively develop the most effective medication strategy with the fewest side effects.

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP)1-3 is a public and academic collaboration started in 1996 to develop evidence- and consensus-based medication treatment algorithms for schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder.

TMAP’s goal is to establish “best practices” to encourage uniformity of care, achieve the best possible patient outcomes, and use mental health care dollars most efficiently. The project includes four phases, in which the treatment algorithms were developed, compared with treatment-as-usual, put into practice, and will undergo periodic updates.4 The next update begins this year.

The comparison of algorithms for treating bipolar mania/hypomania and depression included 409 patients (mean age 38 to 40) with bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. These patients were severely and persistently mentally ill, from a diverse ethnic population, and significantly impaired in functioning.

During 12 months of treatment, psychiatric symptoms diminished more rapidly in patients in the algorithm group—as measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-24)—compared with those receiving usual treatment. After the first 3 months, the usual-treatment patients also showed diminished symptoms. At study’s end, symptom severity between the groups was not significantly different; both groups showed improvement.

Manic and psychotic symptoms—measured by Clinician-Administered Rating Scale subscales (CARS-M)5—improved significantly more in the algorithm group in the first 3 months, and this gap between the two groups was sustained for 12 months. Depressive symptoms declined, but no overall differences were noted between the two groups. Side effect rates and functioning were also similar.

TMAP’s treatment manual (see Related resources) describes clinicians’ preferred tactics and decision points, which we summarize here. The guidelines are an ongoing effort to apply evidence-based medicine to everyday practice and are meant to be adapted to patient needs.

Treatment goals that guided TMAP algorithm development are:

- symptomatic remission

- full return of psychosocial functioning

- prevention of relapse and recurrence.

Suggestions came from controlled clinical trials, open trials, retrospective data analyses, expert clinical consensus, and input from consumers.

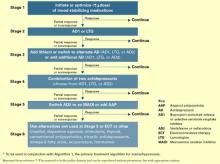

Treatment selection. Initial algorithm stages recommend simple treatments (in terms of safety, tolerability, and side effects), whereas later stages recommend more-complicated regimens. A patient’s symptoms, comorbid conditions, and treatment history guide treatment selection. Patients may enter an algorithm at any stage, depending on their clinical presentation and medication history.

The clinician may consider patient preference when deciding among equivalent medications. The algorithm strongly encourages patients and families to participate, such as by keeping daily mood charts and completing symptom and side-effect checklists. When clinicians face a choice among medication brands, generics, or forms (such as immediate- versus slow-release), agents with greater tolerability are preferred.

Patient management. When patients enter the algorithm, clinic visits are frequent (such as every 2 weeks). Follow-up appointments address medication adherence, dosage adjustments, and side effects or adverse reactions.

If a patient’s symptoms show no change after two treatment stages, re-evaluate the diagnosis and consider mitigating factors such as substance abuse. Patients who complete acute treatment should receive continuation treatment.

Documentation. Clinicians are advised to document decision points and the rationale for treatment choices made outside the algorithm package.

Treating mania or hypomania

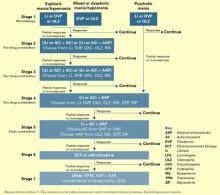

After clinical evaluation confirms the diagnosis of bipolar illness,4 the TMAP mania/hypomania algorithm (Algorithm 1) splits into three treatment pathways:

- euphoric mania/hypomania

- mixed or dysphoric mania/hypomania

- psychotic mania.

These pathways recognize the need for differing approaches to initial monotherapy and later two-drug combinations. If a patient develops persistent or severe depressive symptoms, the bipolar algorithm for a major depressive episode (Algorithm 2) is used during depressive periods with the primary mania algorithm.