User login

Local Factors Play Major Role in Determining Compensation Rates for Pediatric Hospitalists

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

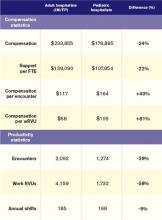

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.