User login

Effectiveness of SIESTA on Objective and Subjective Metrics of Nighttime Hospital Sleep Disruptors

Although sleep is critical to patient recovery in the hospital, hospitalization is not restful,1,2 and inpatient sleep deprivation has been linked to poor health outcomes.1-4 The American Academy of Nursing’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends nurses reduce unnecessary nocturnal care.5 However, interventions to improve inpatient sleep are not widely implemented.6 Targeting routine disruptions, such as overnight vital signs, by changing default settings in the electronic health record (EHR)with “nudges” could be a cost-effective strategy to improve inpatient sleep.4,7

We created Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act (SIESTA), which pairs nudges in the EHR with interprofessional education and empowerment,8 and tested its effectiveness on objectively and subjectively measured nocturnal sleep disruptors.

METHODS

Study Design

Two 18-room University of Chicago Medicine general-medicine units were used in this prospective study. The SIESTA-enhanced unit underwent the full sleep intervention: nursing education and empowerment, physician education, and EHR changes. The standard unit did not receive nursing interventions but received all other forms of intervention. Because physicians simultaneously cared for patients on both units, all internal medicine residents and hospitalists received the same education. The study population included physicians, nurses, and awake English-speaking patients who were cognitively intact and admitted to these two units. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study (12-1766; 16685B).

Development of SIESTA

To develop SIESTA, patients were surveyed, and focus groups of staff were conducted; overnight vitals, medications, and phlebotomy were identified as major barriers to patient sleep.9 We found that physicians did not know how to change the default vital signs order “every 4 hours” or how to batch-order morning phlebotomy at a time other than 4:00

Behavioral Nudges

The SIESTA team worked with clinical informaticists to change the default orders in EpicTM (Epic Systems Corporation, 2017, Verona, Wisconsin) in September 2015 so that physicians would be asked, “Continue vital signs throughout the night?”10 Previously, this question was marked “Yes” by default and hidden. While the default protocol for heparin q8h was maintained, heparin q12h (9:00

SIESTA Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the consequences and causes of in-hospital sleep deprivation and evidence-based behavioral modification. We distributed pocket cards describing the mnemonic SIESTA (Screen patients for sleep disorders, Instruct patients on sleep hygiene, Eliminate disruptions, Shut doors, Treat pain, and Alarm and noise control). Physicians were instructed to consider forgoing overnight vitals, using clinical judgment to identify stable patients, use a sleep-promoting VTE prophylaxis option, and order daily labs at 10:00

SIESTA-Enhanced Unit

In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, nurses received education using pocket cards and were coached to collaborate with physicians to implement sleep-friendly orders. Customized signage depicting empowered nurses advocating for patients was posted near the huddle board. Because these nurses suggested adding SIESTA to the nurses’ ongoing daily huddles at 4:00

Data Collection

Objectively Measured Sleep Disruptors

Adoption of SIESTA orders from March 2015 to March 2016 was assessed with a monthly EpicTM Clarity report. From August 1, 2015 to April 1, 2016, nocturnal room entries were recorded using the GOJO SMARTLINKTM Hand Hygiene system (GOJO Industries Inc., 2017, Akron, Ohio). This system includes two components: the hand-sanitizer dispensers, which track dispenses (numerator), and door-mounted Activity Counters, which use heat sensors that react to body heat emitted by a person passing through the doorway (denominator for hand-hygiene compliance). For our analysis, we only used Activity Counter data, which count room entries and exits, regardless of whether sanitizer was dispensed.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

From June 2015 to March 2016, research assistants administered a 10-item Potential Hospital Sleep Disruptions and Noises Questionnaire (PHSDNQ) to patients in both units. Responses to this questionnaire correlate with actigraphy-based sleep measurements.9,12,13 Surveys were administered every other weekday to patients available to participate (eg, willing to participate, on the unit, awake). Survey data were stored on the REDCap Database (Version 6.14.0; Vanderbilt University, 2016, Nashville, Tennessee). Pre- and post-intervention Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) “top-box ratings” for percent quiet at night and percent pain well controlled were also compared.

Data Analysis

Objectively Measured Potential Sleep Disruptors

The proportion of sleep-friendly orders was analyzed using a two-sample test for proportions pre-post for the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units. The difference in use of SIESTA orders between units was analyzed via multivariable logistic regression, testing for independent associations between post-period, SIESTA-enhanced unit, and an interaction term (post-period × SIESTA unit) on use of sleep-friendly orders.

Room entries per night (11:00

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Per prior studies, we defined a score 2 or higher as “sleep disruption.”9 Differences between units were evaluated via multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between the interaction of post-period × SIESTA-enhanced unit and odds of not reporting a sleep disruption. Significance was denoted as P = .05.

RESULTS

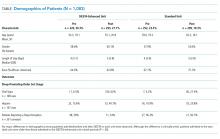

Between March 2015 and March 2016, 1,083 general-medicine patients were admitted to the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units (Table).

Nocturnal Orders

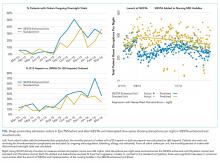

From March 2015 to March 2016, 1,669 EpicTM general medicine orders were reviewed (Figure). In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, the mean percentage of sleep-friendly orders rose for both vital signs (+31% [95% CI = 25%, 36%]; P < .001, npre = 306, npost = 306] and VTE prophylaxis (+28% [95% CI = 18%, 37%]; P < .001, npre = 158, npost = 173]. Similar changes were observed in the standard unit for sleep-friendly vital signs (+20% [95% CI = 14%, 25%]; P < .001, npre = 252, npost = 219) and VTE prophylaxis (+16% [95% CI = 6%, 25%]; P = .002, npre = 130, npost = 125). Differences between the two units were not statistically significant, and no significant change in timing of laboratory orders postintervention was found.

Nighttime Room Entries

Immediately after SIESTA launch, an average decrease of 114 total entries/night were noted in the SIESTA-enhanced unit, ([95% CI = −138, −91]; P < .001), corresponding to a 44% reduction (−6.3 entries/room) from the mean of 14.3 entries per patient room at baseline (Figure). No statistically significant change was seen in the standard unit. After SIESTA was incorporated into nursing huddles, total disruptions/night decreased by 1.31 disruptions/night ([95% CI = −1.64, −0.98]; P < .001) in the SIESTA-enhanced unit; by comparison, no significant changes were observed in the standard unit.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Between June 2015 and March 2016, 201 patient surveys were collected. A significant interaction was observed between the SIESTA-enhanced unit and post-period, and patients in the SIESTA-enhanced unit were more likely to report not being disrupted by medications (OR 4.08 [95% CI = 1.13–14.07]; P = .031) and vital signs (OR 3.35 [95% CI = 1.00–11.2]; P = .05) than those in the standard unit. HCAHPS top-box scores for the SIESTA unit increased by 7% for the “Quiet at night” category and 9% for the “Pain well controlled” category; by comparison, no major changes (>5%) were observed in the standard unit.

DISCUSSION

The present SIESTA intervention demonstrated that physician education coupled with EHR default changes are associated with a significant reduction in orders for overnight vital signs and medication administration in both units. However, addition of nursing education and empowerment in the SIESTA-enhanced unit was associated with fewer nocturnal room entries and improvements in patient-reported outcomes compared with those in the standard unit.

This study presents several implications for hospital initiatives aiming to improve patient sleep.14 Our study is consistent with other research highlighting the hypothesis that altering the default settings of EHR systems can influence physician behavior in a sustainable manner.15 However, our study also finds that, even when sleep-friendly orders are present, creating a sleep-friendly environment likely depends on the unit-based nurses championing the cause. While the initial decrease in nocturnal room entries post-SIESTA eventually faded, sustainable changes were observed only after SIESTA was added to nursing huddles, which illustrates the importance of using multiple methods to nudge staff.

Our study includes a number of limitations. It is not a randomized controlled trial, we cannot assume causality, and contamination was assumed, as residents and hospitalists worked in both units. Our single-site study may not be generalizable. Low HCAHPS response rates (10%-20%) also prevent demonstration of statistically significant differences. Finally, our convenience sampling strategy means not all inpatients were surveyed, and objective sleep duration was not measured.

In summary, at the University of Chicago, SIESTA could be associated with adoption of sleep-friendly vitals and medication orders, a decrease in nighttime room entries, and improved patient experience.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA Grant No. T35AG029795) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI Grant Nos. R25HL116372 and K24HL136859).

1. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review [published online ahead of print February 26, 2016]. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(3). doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2. PubMed

2. Arora VM, Chang KL, Fazal AZ, et al. Objective sleep duration and quality in hospitalized older adults: associations with blood pressure and mood. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2185-2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03644.x. PubMed

3. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. PubMed

4. Manian FA, Manian CJ. Sleep quality in adult hospitalized patients with infection: an observational study. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(1):56-60. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000355. PubMed

5. American Academy of Nursing announced engagement in National Choosing Wisely Campaign. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(1):96-98. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.12.017. PubMed

6. Gathecha E, Rios R, Buenaver LF, Landis R, Howell E, Wright S. Pilot study aiming to support sleep quality and duration during hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):467-472. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2578. PubMed

7. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.10.536. PubMed

8. Thaler R, Sunstein C. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press; 2008.

9. Grossman MN, Anderson SL, Worku A, et al. Awakenings? Patient and hospital staff perceptions of nighttime disruptions and their effect on patient sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):301-306. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6468. PubMed

10. Yoder JC, Yuen TC, Churpek MM, Arora VM, Edelson DP. A prospective study of nighttime vital sign monitoring frequency and risk of clinical deterioration. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1554-1555. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7791. PubMed

11. Phung OJ, Kahn SR, Cook DJ, Murad MH. Dosing frequency of unfractionated heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;140(2):374-381. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3084. PubMed

12. Gabor JY, Cooper AB, Hanly PJ. Sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(1):21-27. PubMed

13. Topf M. Personal and environmental predictors of patient disturbance due to hospital noise. J Appl Psychol. 1985;70(1):22-28. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.22. PubMed

14. Cho HJ, Wray CM, Maione S, et al. Right care in hospital medicine: co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):804-806. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4371-4. PubMed

15. Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1340-1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. PubMed

Although sleep is critical to patient recovery in the hospital, hospitalization is not restful,1,2 and inpatient sleep deprivation has been linked to poor health outcomes.1-4 The American Academy of Nursing’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends nurses reduce unnecessary nocturnal care.5 However, interventions to improve inpatient sleep are not widely implemented.6 Targeting routine disruptions, such as overnight vital signs, by changing default settings in the electronic health record (EHR)with “nudges” could be a cost-effective strategy to improve inpatient sleep.4,7

We created Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act (SIESTA), which pairs nudges in the EHR with interprofessional education and empowerment,8 and tested its effectiveness on objectively and subjectively measured nocturnal sleep disruptors.

METHODS

Study Design

Two 18-room University of Chicago Medicine general-medicine units were used in this prospective study. The SIESTA-enhanced unit underwent the full sleep intervention: nursing education and empowerment, physician education, and EHR changes. The standard unit did not receive nursing interventions but received all other forms of intervention. Because physicians simultaneously cared for patients on both units, all internal medicine residents and hospitalists received the same education. The study population included physicians, nurses, and awake English-speaking patients who were cognitively intact and admitted to these two units. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study (12-1766; 16685B).

Development of SIESTA

To develop SIESTA, patients were surveyed, and focus groups of staff were conducted; overnight vitals, medications, and phlebotomy were identified as major barriers to patient sleep.9 We found that physicians did not know how to change the default vital signs order “every 4 hours” or how to batch-order morning phlebotomy at a time other than 4:00

Behavioral Nudges

The SIESTA team worked with clinical informaticists to change the default orders in EpicTM (Epic Systems Corporation, 2017, Verona, Wisconsin) in September 2015 so that physicians would be asked, “Continue vital signs throughout the night?”10 Previously, this question was marked “Yes” by default and hidden. While the default protocol for heparin q8h was maintained, heparin q12h (9:00

SIESTA Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the consequences and causes of in-hospital sleep deprivation and evidence-based behavioral modification. We distributed pocket cards describing the mnemonic SIESTA (Screen patients for sleep disorders, Instruct patients on sleep hygiene, Eliminate disruptions, Shut doors, Treat pain, and Alarm and noise control). Physicians were instructed to consider forgoing overnight vitals, using clinical judgment to identify stable patients, use a sleep-promoting VTE prophylaxis option, and order daily labs at 10:00

SIESTA-Enhanced Unit

In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, nurses received education using pocket cards and were coached to collaborate with physicians to implement sleep-friendly orders. Customized signage depicting empowered nurses advocating for patients was posted near the huddle board. Because these nurses suggested adding SIESTA to the nurses’ ongoing daily huddles at 4:00

Data Collection

Objectively Measured Sleep Disruptors

Adoption of SIESTA orders from March 2015 to March 2016 was assessed with a monthly EpicTM Clarity report. From August 1, 2015 to April 1, 2016, nocturnal room entries were recorded using the GOJO SMARTLINKTM Hand Hygiene system (GOJO Industries Inc., 2017, Akron, Ohio). This system includes two components: the hand-sanitizer dispensers, which track dispenses (numerator), and door-mounted Activity Counters, which use heat sensors that react to body heat emitted by a person passing through the doorway (denominator for hand-hygiene compliance). For our analysis, we only used Activity Counter data, which count room entries and exits, regardless of whether sanitizer was dispensed.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

From June 2015 to March 2016, research assistants administered a 10-item Potential Hospital Sleep Disruptions and Noises Questionnaire (PHSDNQ) to patients in both units. Responses to this questionnaire correlate with actigraphy-based sleep measurements.9,12,13 Surveys were administered every other weekday to patients available to participate (eg, willing to participate, on the unit, awake). Survey data were stored on the REDCap Database (Version 6.14.0; Vanderbilt University, 2016, Nashville, Tennessee). Pre- and post-intervention Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) “top-box ratings” for percent quiet at night and percent pain well controlled were also compared.

Data Analysis

Objectively Measured Potential Sleep Disruptors

The proportion of sleep-friendly orders was analyzed using a two-sample test for proportions pre-post for the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units. The difference in use of SIESTA orders between units was analyzed via multivariable logistic regression, testing for independent associations between post-period, SIESTA-enhanced unit, and an interaction term (post-period × SIESTA unit) on use of sleep-friendly orders.

Room entries per night (11:00

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Per prior studies, we defined a score 2 or higher as “sleep disruption.”9 Differences between units were evaluated via multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between the interaction of post-period × SIESTA-enhanced unit and odds of not reporting a sleep disruption. Significance was denoted as P = .05.

RESULTS

Between March 2015 and March 2016, 1,083 general-medicine patients were admitted to the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units (Table).

Nocturnal Orders

From March 2015 to March 2016, 1,669 EpicTM general medicine orders were reviewed (Figure). In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, the mean percentage of sleep-friendly orders rose for both vital signs (+31% [95% CI = 25%, 36%]; P < .001, npre = 306, npost = 306] and VTE prophylaxis (+28% [95% CI = 18%, 37%]; P < .001, npre = 158, npost = 173]. Similar changes were observed in the standard unit for sleep-friendly vital signs (+20% [95% CI = 14%, 25%]; P < .001, npre = 252, npost = 219) and VTE prophylaxis (+16% [95% CI = 6%, 25%]; P = .002, npre = 130, npost = 125). Differences between the two units were not statistically significant, and no significant change in timing of laboratory orders postintervention was found.

Nighttime Room Entries

Immediately after SIESTA launch, an average decrease of 114 total entries/night were noted in the SIESTA-enhanced unit, ([95% CI = −138, −91]; P < .001), corresponding to a 44% reduction (−6.3 entries/room) from the mean of 14.3 entries per patient room at baseline (Figure). No statistically significant change was seen in the standard unit. After SIESTA was incorporated into nursing huddles, total disruptions/night decreased by 1.31 disruptions/night ([95% CI = −1.64, −0.98]; P < .001) in the SIESTA-enhanced unit; by comparison, no significant changes were observed in the standard unit.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Between June 2015 and March 2016, 201 patient surveys were collected. A significant interaction was observed between the SIESTA-enhanced unit and post-period, and patients in the SIESTA-enhanced unit were more likely to report not being disrupted by medications (OR 4.08 [95% CI = 1.13–14.07]; P = .031) and vital signs (OR 3.35 [95% CI = 1.00–11.2]; P = .05) than those in the standard unit. HCAHPS top-box scores for the SIESTA unit increased by 7% for the “Quiet at night” category and 9% for the “Pain well controlled” category; by comparison, no major changes (>5%) were observed in the standard unit.

DISCUSSION

The present SIESTA intervention demonstrated that physician education coupled with EHR default changes are associated with a significant reduction in orders for overnight vital signs and medication administration in both units. However, addition of nursing education and empowerment in the SIESTA-enhanced unit was associated with fewer nocturnal room entries and improvements in patient-reported outcomes compared with those in the standard unit.

This study presents several implications for hospital initiatives aiming to improve patient sleep.14 Our study is consistent with other research highlighting the hypothesis that altering the default settings of EHR systems can influence physician behavior in a sustainable manner.15 However, our study also finds that, even when sleep-friendly orders are present, creating a sleep-friendly environment likely depends on the unit-based nurses championing the cause. While the initial decrease in nocturnal room entries post-SIESTA eventually faded, sustainable changes were observed only after SIESTA was added to nursing huddles, which illustrates the importance of using multiple methods to nudge staff.

Our study includes a number of limitations. It is not a randomized controlled trial, we cannot assume causality, and contamination was assumed, as residents and hospitalists worked in both units. Our single-site study may not be generalizable. Low HCAHPS response rates (10%-20%) also prevent demonstration of statistically significant differences. Finally, our convenience sampling strategy means not all inpatients were surveyed, and objective sleep duration was not measured.

In summary, at the University of Chicago, SIESTA could be associated with adoption of sleep-friendly vitals and medication orders, a decrease in nighttime room entries, and improved patient experience.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA Grant No. T35AG029795) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI Grant Nos. R25HL116372 and K24HL136859).

Although sleep is critical to patient recovery in the hospital, hospitalization is not restful,1,2 and inpatient sleep deprivation has been linked to poor health outcomes.1-4 The American Academy of Nursing’s Choosing Wisely® campaign recommends nurses reduce unnecessary nocturnal care.5 However, interventions to improve inpatient sleep are not widely implemented.6 Targeting routine disruptions, such as overnight vital signs, by changing default settings in the electronic health record (EHR)with “nudges” could be a cost-effective strategy to improve inpatient sleep.4,7

We created Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act (SIESTA), which pairs nudges in the EHR with interprofessional education and empowerment,8 and tested its effectiveness on objectively and subjectively measured nocturnal sleep disruptors.

METHODS

Study Design

Two 18-room University of Chicago Medicine general-medicine units were used in this prospective study. The SIESTA-enhanced unit underwent the full sleep intervention: nursing education and empowerment, physician education, and EHR changes. The standard unit did not receive nursing interventions but received all other forms of intervention. Because physicians simultaneously cared for patients on both units, all internal medicine residents and hospitalists received the same education. The study population included physicians, nurses, and awake English-speaking patients who were cognitively intact and admitted to these two units. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study (12-1766; 16685B).

Development of SIESTA

To develop SIESTA, patients were surveyed, and focus groups of staff were conducted; overnight vitals, medications, and phlebotomy were identified as major barriers to patient sleep.9 We found that physicians did not know how to change the default vital signs order “every 4 hours” or how to batch-order morning phlebotomy at a time other than 4:00

Behavioral Nudges

The SIESTA team worked with clinical informaticists to change the default orders in EpicTM (Epic Systems Corporation, 2017, Verona, Wisconsin) in September 2015 so that physicians would be asked, “Continue vital signs throughout the night?”10 Previously, this question was marked “Yes” by default and hidden. While the default protocol for heparin q8h was maintained, heparin q12h (9:00

SIESTA Physician Education

We created a 20-minute presentation on the consequences and causes of in-hospital sleep deprivation and evidence-based behavioral modification. We distributed pocket cards describing the mnemonic SIESTA (Screen patients for sleep disorders, Instruct patients on sleep hygiene, Eliminate disruptions, Shut doors, Treat pain, and Alarm and noise control). Physicians were instructed to consider forgoing overnight vitals, using clinical judgment to identify stable patients, use a sleep-promoting VTE prophylaxis option, and order daily labs at 10:00

SIESTA-Enhanced Unit

In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, nurses received education using pocket cards and were coached to collaborate with physicians to implement sleep-friendly orders. Customized signage depicting empowered nurses advocating for patients was posted near the huddle board. Because these nurses suggested adding SIESTA to the nurses’ ongoing daily huddles at 4:00

Data Collection

Objectively Measured Sleep Disruptors

Adoption of SIESTA orders from March 2015 to March 2016 was assessed with a monthly EpicTM Clarity report. From August 1, 2015 to April 1, 2016, nocturnal room entries were recorded using the GOJO SMARTLINKTM Hand Hygiene system (GOJO Industries Inc., 2017, Akron, Ohio). This system includes two components: the hand-sanitizer dispensers, which track dispenses (numerator), and door-mounted Activity Counters, which use heat sensors that react to body heat emitted by a person passing through the doorway (denominator for hand-hygiene compliance). For our analysis, we only used Activity Counter data, which count room entries and exits, regardless of whether sanitizer was dispensed.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

From June 2015 to March 2016, research assistants administered a 10-item Potential Hospital Sleep Disruptions and Noises Questionnaire (PHSDNQ) to patients in both units. Responses to this questionnaire correlate with actigraphy-based sleep measurements.9,12,13 Surveys were administered every other weekday to patients available to participate (eg, willing to participate, on the unit, awake). Survey data were stored on the REDCap Database (Version 6.14.0; Vanderbilt University, 2016, Nashville, Tennessee). Pre- and post-intervention Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) “top-box ratings” for percent quiet at night and percent pain well controlled were also compared.

Data Analysis

Objectively Measured Potential Sleep Disruptors

The proportion of sleep-friendly orders was analyzed using a two-sample test for proportions pre-post for the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units. The difference in use of SIESTA orders between units was analyzed via multivariable logistic regression, testing for independent associations between post-period, SIESTA-enhanced unit, and an interaction term (post-period × SIESTA unit) on use of sleep-friendly orders.

Room entries per night (11:00

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Per prior studies, we defined a score 2 or higher as “sleep disruption.”9 Differences between units were evaluated via multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between the interaction of post-period × SIESTA-enhanced unit and odds of not reporting a sleep disruption. Significance was denoted as P = .05.

RESULTS

Between March 2015 and March 2016, 1,083 general-medicine patients were admitted to the SIESTA-enhanced and standard units (Table).

Nocturnal Orders

From March 2015 to March 2016, 1,669 EpicTM general medicine orders were reviewed (Figure). In the SIESTA-enhanced unit, the mean percentage of sleep-friendly orders rose for both vital signs (+31% [95% CI = 25%, 36%]; P < .001, npre = 306, npost = 306] and VTE prophylaxis (+28% [95% CI = 18%, 37%]; P < .001, npre = 158, npost = 173]. Similar changes were observed in the standard unit for sleep-friendly vital signs (+20% [95% CI = 14%, 25%]; P < .001, npre = 252, npost = 219) and VTE prophylaxis (+16% [95% CI = 6%, 25%]; P = .002, npre = 130, npost = 125). Differences between the two units were not statistically significant, and no significant change in timing of laboratory orders postintervention was found.

Nighttime Room Entries

Immediately after SIESTA launch, an average decrease of 114 total entries/night were noted in the SIESTA-enhanced unit, ([95% CI = −138, −91]; P < .001), corresponding to a 44% reduction (−6.3 entries/room) from the mean of 14.3 entries per patient room at baseline (Figure). No statistically significant change was seen in the standard unit. After SIESTA was incorporated into nursing huddles, total disruptions/night decreased by 1.31 disruptions/night ([95% CI = −1.64, −0.98]; P < .001) in the SIESTA-enhanced unit; by comparison, no significant changes were observed in the standard unit.

Patient-Reported Nighttime Sleep Disruptions

Between June 2015 and March 2016, 201 patient surveys were collected. A significant interaction was observed between the SIESTA-enhanced unit and post-period, and patients in the SIESTA-enhanced unit were more likely to report not being disrupted by medications (OR 4.08 [95% CI = 1.13–14.07]; P = .031) and vital signs (OR 3.35 [95% CI = 1.00–11.2]; P = .05) than those in the standard unit. HCAHPS top-box scores for the SIESTA unit increased by 7% for the “Quiet at night” category and 9% for the “Pain well controlled” category; by comparison, no major changes (>5%) were observed in the standard unit.

DISCUSSION

The present SIESTA intervention demonstrated that physician education coupled with EHR default changes are associated with a significant reduction in orders for overnight vital signs and medication administration in both units. However, addition of nursing education and empowerment in the SIESTA-enhanced unit was associated with fewer nocturnal room entries and improvements in patient-reported outcomes compared with those in the standard unit.

This study presents several implications for hospital initiatives aiming to improve patient sleep.14 Our study is consistent with other research highlighting the hypothesis that altering the default settings of EHR systems can influence physician behavior in a sustainable manner.15 However, our study also finds that, even when sleep-friendly orders are present, creating a sleep-friendly environment likely depends on the unit-based nurses championing the cause. While the initial decrease in nocturnal room entries post-SIESTA eventually faded, sustainable changes were observed only after SIESTA was added to nursing huddles, which illustrates the importance of using multiple methods to nudge staff.

Our study includes a number of limitations. It is not a randomized controlled trial, we cannot assume causality, and contamination was assumed, as residents and hospitalists worked in both units. Our single-site study may not be generalizable. Low HCAHPS response rates (10%-20%) also prevent demonstration of statistically significant differences. Finally, our convenience sampling strategy means not all inpatients were surveyed, and objective sleep duration was not measured.

In summary, at the University of Chicago, SIESTA could be associated with adoption of sleep-friendly vitals and medication orders, a decrease in nighttime room entries, and improved patient experience.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA Grant No. T35AG029795) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI Grant Nos. R25HL116372 and K24HL136859).

1. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review [published online ahead of print February 26, 2016]. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(3). doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2. PubMed

2. Arora VM, Chang KL, Fazal AZ, et al. Objective sleep duration and quality in hospitalized older adults: associations with blood pressure and mood. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2185-2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03644.x. PubMed

3. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. PubMed

4. Manian FA, Manian CJ. Sleep quality in adult hospitalized patients with infection: an observational study. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(1):56-60. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000355. PubMed

5. American Academy of Nursing announced engagement in National Choosing Wisely Campaign. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(1):96-98. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.12.017. PubMed

6. Gathecha E, Rios R, Buenaver LF, Landis R, Howell E, Wright S. Pilot study aiming to support sleep quality and duration during hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):467-472. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2578. PubMed

7. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.10.536. PubMed

8. Thaler R, Sunstein C. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press; 2008.

9. Grossman MN, Anderson SL, Worku A, et al. Awakenings? Patient and hospital staff perceptions of nighttime disruptions and their effect on patient sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):301-306. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6468. PubMed

10. Yoder JC, Yuen TC, Churpek MM, Arora VM, Edelson DP. A prospective study of nighttime vital sign monitoring frequency and risk of clinical deterioration. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1554-1555. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7791. PubMed

11. Phung OJ, Kahn SR, Cook DJ, Murad MH. Dosing frequency of unfractionated heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;140(2):374-381. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3084. PubMed

12. Gabor JY, Cooper AB, Hanly PJ. Sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(1):21-27. PubMed

13. Topf M. Personal and environmental predictors of patient disturbance due to hospital noise. J Appl Psychol. 1985;70(1):22-28. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.22. PubMed

14. Cho HJ, Wray CM, Maione S, et al. Right care in hospital medicine: co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):804-806. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4371-4. PubMed

15. Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1340-1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. PubMed

1. Delaney LJ, Van Haren F, Lopez V. Sleeping on a problem: the impact of sleep disturbance on intensive care patients - a clinical review [published online ahead of print February 26, 2016]. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(3). doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0043-2. PubMed

2. Arora VM, Chang KL, Fazal AZ, et al. Objective sleep duration and quality in hospitalized older adults: associations with blood pressure and mood. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2185-2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03644.x. PubMed

3. Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11(3):163-178. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. PubMed

4. Manian FA, Manian CJ. Sleep quality in adult hospitalized patients with infection: an observational study. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(1):56-60. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000355. PubMed

5. American Academy of Nursing announced engagement in National Choosing Wisely Campaign. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(1):96-98. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.12.017. PubMed

6. Gathecha E, Rios R, Buenaver LF, Landis R, Howell E, Wright S. Pilot study aiming to support sleep quality and duration during hospitalizations. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(7):467-472. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2578. PubMed

7. Fillary J, Chaplin H, Jones G, Thompson A, Holme A, Wilson P. Noise at night in hospital general wards: a mapping of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(10):536-540. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.10.536. PubMed

8. Thaler R, Sunstein C. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press; 2008.

9. Grossman MN, Anderson SL, Worku A, et al. Awakenings? Patient and hospital staff perceptions of nighttime disruptions and their effect on patient sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):301-306. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6468. PubMed

10. Yoder JC, Yuen TC, Churpek MM, Arora VM, Edelson DP. A prospective study of nighttime vital sign monitoring frequency and risk of clinical deterioration. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1554-1555. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7791. PubMed

11. Phung OJ, Kahn SR, Cook DJ, Murad MH. Dosing frequency of unfractionated heparin thromboprophylaxis: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;140(2):374-381. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3084. PubMed

12. Gabor JY, Cooper AB, Hanly PJ. Sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(1):21-27. PubMed

13. Topf M. Personal and environmental predictors of patient disturbance due to hospital noise. J Appl Psychol. 1985;70(1):22-28. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.70.1.22. PubMed

14. Cho HJ, Wray CM, Maione S, et al. Right care in hospital medicine: co-creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):804-806. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4371-4. PubMed

15. Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1340-1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb071595. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Letter to the Editor

We read with great interest the study by Butcher and colleagues[1] on resident perceptions of rapid response teams (RRTs) with regard to education and autonomy. We found it interesting to note that one‐third of residents felt the nurse should always notify the primary resident when calling an RRT. Nursing literature demonstrates that ambivalence exists on when to notify the physician,[2] thus suggesting nurse‐physician interactions are still suboptimal and an area for future improvement. Given the focus on interprofessional training and practice by both the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education and Liaison Committee on Medical Education,[3, 4] RRTs provide a perfect opportunity to improve interprofessional training and practice through better physician‐nurse collaboration.

Interestingly, the future of RRT activation can also be streamlined to avoid nurse‐physician conflicts about who should be notified. For example, the technology exists for automated alerts in the electronic medical record to trigger when a patient decompensates,[5] thereby activating an RRT. One can imagine this technology circumvents the physician and nurse when initiating the RRT. Given the potential uses of such technology, future studies regarding physician autonomy with automatic triggering of an RRT will be equally valuable.

- , , , The effect of a rapid response team on resident perceptions of education and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):8–12.

- , , , , Qualitative exploration of nurses' decisions to activate rapid response teams. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(19‐20):2876–2882.

- , , , et al.; Internal Medicine Milestone Group. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and The American Board of Internal Medicine. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 2013 summary of new and revised LCME accreditation standards and annotations. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/2013‐new‐and_revised‐standards‐summary.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- , , , , , Derivation of a cardiac arrest prediction model using ward vital signs. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2102–2108.

We read with great interest the study by Butcher and colleagues[1] on resident perceptions of rapid response teams (RRTs) with regard to education and autonomy. We found it interesting to note that one‐third of residents felt the nurse should always notify the primary resident when calling an RRT. Nursing literature demonstrates that ambivalence exists on when to notify the physician,[2] thus suggesting nurse‐physician interactions are still suboptimal and an area for future improvement. Given the focus on interprofessional training and practice by both the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education and Liaison Committee on Medical Education,[3, 4] RRTs provide a perfect opportunity to improve interprofessional training and practice through better physician‐nurse collaboration.

Interestingly, the future of RRT activation can also be streamlined to avoid nurse‐physician conflicts about who should be notified. For example, the technology exists for automated alerts in the electronic medical record to trigger when a patient decompensates,[5] thereby activating an RRT. One can imagine this technology circumvents the physician and nurse when initiating the RRT. Given the potential uses of such technology, future studies regarding physician autonomy with automatic triggering of an RRT will be equally valuable.

We read with great interest the study by Butcher and colleagues[1] on resident perceptions of rapid response teams (RRTs) with regard to education and autonomy. We found it interesting to note that one‐third of residents felt the nurse should always notify the primary resident when calling an RRT. Nursing literature demonstrates that ambivalence exists on when to notify the physician,[2] thus suggesting nurse‐physician interactions are still suboptimal and an area for future improvement. Given the focus on interprofessional training and practice by both the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education and Liaison Committee on Medical Education,[3, 4] RRTs provide a perfect opportunity to improve interprofessional training and practice through better physician‐nurse collaboration.

Interestingly, the future of RRT activation can also be streamlined to avoid nurse‐physician conflicts about who should be notified. For example, the technology exists for automated alerts in the electronic medical record to trigger when a patient decompensates,[5] thereby activating an RRT. One can imagine this technology circumvents the physician and nurse when initiating the RRT. Given the potential uses of such technology, future studies regarding physician autonomy with automatic triggering of an RRT will be equally valuable.

- , , , The effect of a rapid response team on resident perceptions of education and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):8–12.

- , , , , Qualitative exploration of nurses' decisions to activate rapid response teams. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(19‐20):2876–2882.

- , , , et al.; Internal Medicine Milestone Group. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and The American Board of Internal Medicine. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 2013 summary of new and revised LCME accreditation standards and annotations. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/2013‐new‐and_revised‐standards‐summary.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- , , , , , Derivation of a cardiac arrest prediction model using ward vital signs. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2102–2108.

- , , , The effect of a rapid response team on resident perceptions of education and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):8–12.

- , , , , Qualitative exploration of nurses' decisions to activate rapid response teams. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(19‐20):2876–2882.

- , , , et al.; Internal Medicine Milestone Group. The Internal Medicine Milestone Project. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and The American Board of Internal Medicine. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. 2013 summary of new and revised LCME accreditation standards and annotations. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/2013‐new‐and_revised‐standards‐summary.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- , , , , , Derivation of a cardiac arrest prediction model using ward vital signs. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2102–2108.