User login

Office hysteroscopy offers many benefits and is becoming more acceptable among patients and gynecologists for both diagnostic and operative procedures (TABLE 1). Despite its clear advantages, however, many gynecologists remain hesitant to perform in-office procedures out of fear that the patient, who is generally awake, will experience significant discomfort.

Certainly, pain and low patient tolerance of discomfort have been the primary limitations to widespread use of office hysteroscopy without anesthesia.1 Data on the use of anesthesia for office hysteroscopy—especially diagnostic procedures—historically have been inconsistent in regard to the reduction of patient discomfort.2

Bettocchi and Selvaggi first reported a vaginoscopic approach to diagnostic hysteroscopy to reduce the discomfort of the procedure, compared with the conventional approach. They did not place a vaginal speculum or tenaculum and, therefore, avoided placing local anesthetic into the cervix.3

A randomized controlled trial by Sagiv and colleagues found reduced pain during diagnostic hysteroscopy with vaginoscopy (VIDEO).4

In 2004, Bettocchi and colleagues reported nearly 5,000 operative hysteroscopic procedures performed with this technique (the “no-touch” technique) in an outpatient setting, demonstrating very high patient tolerance and a low degree of procedural pain. More than 90% of patients experienced little to no pain, except for those undergoing polypectomy when the polyps were larger than the diameter of the cervical os, as well as those who had anatomic abnormalities, with moderate discomfort reported by 33.2% and 12.7% of these women, respectively.5 These few patients may have benefited from anesthetic intervention for the procedure.

In a 2010 review of the literature on hysteroscopy without anesthesia, Cicinelli found that diagnostic hysteroscopy was more successful, with less patient discomfort, when smaller hysteroscopes were used (3.5 mm or smaller, including flexible lenses) and when the approach was vaginoscopic.1 Reduced pain with operative procedures was associated with a number of variables, including:

- increased surgeon experience

- smaller instrument size

- shorter duration of the procedure

- premenopausal status.

Variables associated with increased pain during operative procedures included:

- chronic pelvic pain

- menopausal status

- previous cesarean delivery

- significant anxiety.

In the review, Cicinelli noted that not all patients are likely to have a successful hysteroscopic procedure without the use of anesthesia or analgesia, regardless of the approach used.1

Only 1 randomized controlled trial explored the use of anesthesia (versus placebo) during operative hysteroscopy, and the authors found a benefit for preprocedural paracervical block using local anesthetic to reduce cervical pain.6

The success of diagnostic and operative hysteroscopic procedures with minimal and acceptable levels of patient discomfort in the office depends, therefore, on multiple factors. Procedural factors affecting the outcome of hysteroscopy include the size of the instrument used, the type and length of the procedure, the use of preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, and a vaginoscopic approach. The skill of the surgeon also affects the hysteroscopic experience and outcome. In addition, patient variables such as menopausal status, anatomic distortion (eg, cervical stenosis), and anxiety may adversely affect the patient’s experience.

In summary, it is possible for the gynecologist to appropriately accommodate any given patient and clinical scenario, keeping in mind that many patients will require a customized approach for ultimate success. In this article, I review 3 recent studies on office hysteroscopy, focusing on the reduction of procedural pain and anxiety. Because of the protective effect of a high degree of surgeon experience, it is important that we offer adequate education in hysteroscopy during residency and postgraduate courses.

Placement of local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites facilitates patient comfort during hysteroscopy

Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

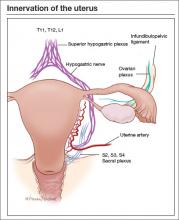

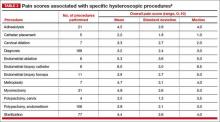

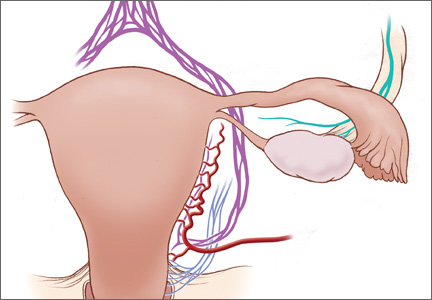

In a 2010 review of randomized controlled trials of the use of local anesthesia versus placebo during hysteroscopy, data from several studies indicated a significant decrease in procedural pain when local anesthesia was given, while other studies found no difference.2 Most of the studies in that review evaluated a single site of anesthesia placement and focused on diagnostic hysteroscopy. The findings of that review, as well as the differential innervation of the uterine cervix and fundus (FIGURE), prompted Keyhan and Munro to evaluate the efficacy of multimodal local anesthetic for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy without the use of any systemic agents except for preprocedural cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors (TABLE 2). Accordingly, they placed local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites to alleviate patient pain and improve procedural success in a spectrum of office-based hysteroscopic procedures.

Details of the trial

Procedures generally were performed using a continuous-flow sheath with an outside diameter of 5.5 mm and a 5 French operative channel for placement of operative instruments such as scissors, graspers, and sterilization microinserts. Normal saline or sterile water was used as the uterine distention medium, with gravity inflow assisted by pressure cuff, when necessary. Occasionally, a sheath system with an outside diameter of 6.5 mm was used, or an outside diameter of 9 mm for resectoscopic procedures using a bipolar radiofrequency resectoscope. When needed, cervical dilation was performed to accommodate the specific instrument used.

The impact of the multimodal, multisite anesthetic protocol was evaluated using contemporaneous patient reporting of numeric pain scores (worst pain experienced) that included anesthesia-related pain, procedure-related pain, and overall pain.

A total of 478 women underwent 535 procedures. A patient verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess the worst pain experienced. The overall mean (SD) procedure pain score was 3.7 (2.5). The mean score for patients undergoing diagnostic hysteroscopy was 3.2 (2.5), and it was 4.1 (2.5) for operative hysteroscopy (P<.001).

TABLE 3 shows the procedures performed under the anesthetic protocol. Pain associated with placement of anesthesia was similar for diagnostic and operative procedures (mean score, 2.7), but the mean overall pain scores for diagnostic procedures were about 1 unit less than for operative procedures, regardless of age or delivery history.

Complications were limited to 3 transient vasovagal episodes. Five procedures could not be completed because of intolerable pain or inability to access the uterine cavity. There was no difference in pain scores between menopausal and premeno-pausal women.

Malcolm G. Munro, MD, offers a protocol for pain relief during hysteroscopy

In this video, Malcolm G. Munro, MD, makes use of both topical and injectable lidocaine at 5 anatomic sites

Dr. Munro is Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Director of Gynecologic Services at Kaiser Permanente, Los Angeles Medical Center, in Los Angeles, California.

When placing anesthesia at multiple sites, allow time for onset of action

Keyhan and Munro demonstrated that successful completion of hysteroscopic procedures in the office environment can be achieved with acceptable levels of patient discomfort using a multimodal, multisite approach for preemptive placement of local anesthetic in the vagina, cervix, and endometrial cavity. They emphasize that the waiting time allotted for the onset of anesthesia is critical to the success of this approach. They also stress that no preprocedure oral sedative or narcotic is used with their approach. In addition, they note that the minimal discomfort experienced during placement of local anesthetic was overshadowed by general comfort during the wide spectrum of procedures performed.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The placement of preemptive local anesthesia at multiple anatomic sites facilitates diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy with an acceptable degree of patient comfort and successful completion of office procedures.

Music may reduce patient anxiety during hysteroscopy

Angioli R, De Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

Angioli and colleagues set out to address another factor that can impede patient comfort during office hysteroscopy—anxiety. Their randomized prospective trial is the only such trial evaluating the use of music to establish a calm and relaxing environment prior to office hysteroscopy for patients who are awake. Music supports an environment that “stimulates and maintains relaxation, well-being, and comfort and can be used as a self-management technique to reduce or control distress,” Angioli and colleagues write. The theory is that music distracts the patient by drawing her attention away from negative stimuli, thereby reducing pain, anxiety, and stress.

Details of the trial

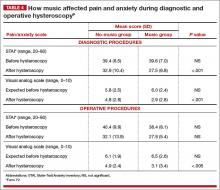

A standardized visual analog scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess patient discomfort, and a State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; range, 20–80) also was given. Both tools were administered at baseline. The visual analog scale was measured again during the procedure, and the STAI was administered again after the procedure.

A hysteroscopic sheath with an outside diameter of 5 mm was used with a 5 French operative channel, and a vaginoscopic approach was used for each hysteroscopic procedure. A total of 372 women were enrolled and randomly allocated to either:

- music group (n = 185)

- no-music group (n = 187).

The surgical procedure was not completed in 15 patients (9 in the music group and 6 in the no-music group) because of stenosis of the cervix and/or excessive pain.

Women in the music group were allowed to select a playlist of classical, pop, jazz, or rock music that was played through a speaker system in the room. Of these patients, 50% preferred classical, 45% preferred pop, 5% chose jazz, and none selected rock music.

There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of preprocedure wait time, preprocedure scores on the visual analog scale or STAI, preprocedure vital signs, patient characteristics, type of procedure, or duration of the procedure. However, the music group had a lower visual analog score during the procedure and a lower postoperative STAI for diagnostic hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. The music group also had a statistically significant lower visual analog score for operative hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. In addition, the music group had a lower postoperative STAI score than the no-music group, but this difference was not statistically significant (TABLE 4).

Interestingly, in the music group, the STAI scores were lower after both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy when classical music was selected rather than pop music.

Anxiety and pain are highly correlated

Angioli and colleagues found that patients who listened to music intraoperatively had a lower perception of pain and less anxiety. In addition, systolic blood pressure and heart rate were significantly lower in the music group than the no-music group, implying that patients who listened to music experienced less physical stress during the procedure.

Angioli and colleagues also noted that the level of anxiety and perception of pain were highly correlated. Pain is not an emotionally neutral experience but is almost always accompanied by distress. Investigators concluded that “anxiety can enhance painful sensations at all levels of the nervous system, from the peripheral receptors to the cortical level.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Music is a useful complementary method to control patient anxiety and reduce the perception of pain during office hysteroscopy by creating a more relaxed and comfortable environment.

What are the risk factors for pain and discomfort during office hysteroscopy?

De Freitas FM, Sessa FV, Resende AD Jr, et al. Identifying predictors of unacceptable pain at office hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):586–591.

De Freitas and colleagues conducted their prospective observational study to identify predictors of unacceptable pain during diagnostic office hysteroscopy (with or without directed or curette endometrial biopsy) and at the time of discharge. They hoped that any identifiable causes of unacceptable pain could be addressed individually in future patients undergoing office hysteroscopy to reduce their level of discomfort.

Details of the trial

A total of 558 procedures were evaluated. Hysteroscopists had varying levels of experience, with some having performed fewer than 50 procedures and others having performed more than 500.

A verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess pain at the end of each procedure and at the time of discharge. Investigators considered a score of 7 or more at the time of the procedure and a score of 4 or more at the time of discharge to be unacceptable.

A diagnostic, single-channel hysteroscope with an outside diameter of 3.5 mm was used with normal saline (at room temperature), along with a gravity system with pressure established to maintain intrauterine pressure at approximately 110 mm Hg. All hysteroscopic procedures were performed using a vaginoscopic approach, and biopsies were obtained as clinically indicated. Any patients who reported cramping at discharge (ie, a verbal response scale score of 4 or more) were offered an oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Overall, the prevalence of unacceptable pain during office hysteroscopy was 32.3%. Experience of the hysteroscopist had a significant protective effect against pain. Longer procedures were significantly associated with unacceptable procedural pain.

The prevalence of unacceptable cramping at discharge was 28.6%. The risk of discomfort at discharge was significantly higher for women who reported dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea. Surgeon experience was significantly protective against unacceptable pain at discharge, and longer procedures were significantly associated with increased discomfort at discharge.

Dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia were significant predictors of pain at discharge

In this study, dysmenorrhea was a significant predictor of unacceptable pain at discharge, increasing the risk of unacceptable cramps by approximately threefold. Women who reported dyspareunia were nearly twice as likely to report unacceptable cramping at discharge.

Although a high level of expertise is not a prerequisite for office hysteroscopy, the skill and experience of the hysteroscopist, as well as shorter procedures, proved to be protective against procedural pain and discomfort at discharge but did not eliminate them altogether. Therefore, De Freitas and colleagues recommend that patients who can be identified as high-risk for procedural or discharge pain, such as women with dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia, should be offered preprocedure analgesia and/or anesthesia to reduce overall discomfort.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

If a patient reports dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia preoperatively, she may benefit from preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, or both, in an office setting.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):703–708.

2. Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

3. Bettocchi S, Selvaggi L. A vaginoscopic approach to reduce the pain of office hysteroscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(2):255–258.

4. Sagiv R, Sadan O, Boaz M, et al. A new approach to office hysteroscopy compared with traditional hysteroscopy. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):387–392.

5.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Nappi L, et al. Operative office hysteroscopy without anesthesia: analysis of 4,863 cases performed with mechanical instruments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(1):59–61.

6. Chudnoff S, Einstein M, Levie M. Paracervical block efficacy in office hysteroscopic sterilization. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):26–34.

7. Garcia AL. Stop performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2013;25(6):44–48.

8. Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

9. Angioli R, de Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

Office hysteroscopy offers many benefits and is becoming more acceptable among patients and gynecologists for both diagnostic and operative procedures (TABLE 1). Despite its clear advantages, however, many gynecologists remain hesitant to perform in-office procedures out of fear that the patient, who is generally awake, will experience significant discomfort.

Certainly, pain and low patient tolerance of discomfort have been the primary limitations to widespread use of office hysteroscopy without anesthesia.1 Data on the use of anesthesia for office hysteroscopy—especially diagnostic procedures—historically have been inconsistent in regard to the reduction of patient discomfort.2

Bettocchi and Selvaggi first reported a vaginoscopic approach to diagnostic hysteroscopy to reduce the discomfort of the procedure, compared with the conventional approach. They did not place a vaginal speculum or tenaculum and, therefore, avoided placing local anesthetic into the cervix.3

A randomized controlled trial by Sagiv and colleagues found reduced pain during diagnostic hysteroscopy with vaginoscopy (VIDEO).4

In 2004, Bettocchi and colleagues reported nearly 5,000 operative hysteroscopic procedures performed with this technique (the “no-touch” technique) in an outpatient setting, demonstrating very high patient tolerance and a low degree of procedural pain. More than 90% of patients experienced little to no pain, except for those undergoing polypectomy when the polyps were larger than the diameter of the cervical os, as well as those who had anatomic abnormalities, with moderate discomfort reported by 33.2% and 12.7% of these women, respectively.5 These few patients may have benefited from anesthetic intervention for the procedure.

In a 2010 review of the literature on hysteroscopy without anesthesia, Cicinelli found that diagnostic hysteroscopy was more successful, with less patient discomfort, when smaller hysteroscopes were used (3.5 mm or smaller, including flexible lenses) and when the approach was vaginoscopic.1 Reduced pain with operative procedures was associated with a number of variables, including:

- increased surgeon experience

- smaller instrument size

- shorter duration of the procedure

- premenopausal status.

Variables associated with increased pain during operative procedures included:

- chronic pelvic pain

- menopausal status

- previous cesarean delivery

- significant anxiety.

In the review, Cicinelli noted that not all patients are likely to have a successful hysteroscopic procedure without the use of anesthesia or analgesia, regardless of the approach used.1

Only 1 randomized controlled trial explored the use of anesthesia (versus placebo) during operative hysteroscopy, and the authors found a benefit for preprocedural paracervical block using local anesthetic to reduce cervical pain.6

The success of diagnostic and operative hysteroscopic procedures with minimal and acceptable levels of patient discomfort in the office depends, therefore, on multiple factors. Procedural factors affecting the outcome of hysteroscopy include the size of the instrument used, the type and length of the procedure, the use of preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, and a vaginoscopic approach. The skill of the surgeon also affects the hysteroscopic experience and outcome. In addition, patient variables such as menopausal status, anatomic distortion (eg, cervical stenosis), and anxiety may adversely affect the patient’s experience.

In summary, it is possible for the gynecologist to appropriately accommodate any given patient and clinical scenario, keeping in mind that many patients will require a customized approach for ultimate success. In this article, I review 3 recent studies on office hysteroscopy, focusing on the reduction of procedural pain and anxiety. Because of the protective effect of a high degree of surgeon experience, it is important that we offer adequate education in hysteroscopy during residency and postgraduate courses.

Placement of local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites facilitates patient comfort during hysteroscopy

Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

In a 2010 review of randomized controlled trials of the use of local anesthesia versus placebo during hysteroscopy, data from several studies indicated a significant decrease in procedural pain when local anesthesia was given, while other studies found no difference.2 Most of the studies in that review evaluated a single site of anesthesia placement and focused on diagnostic hysteroscopy. The findings of that review, as well as the differential innervation of the uterine cervix and fundus (FIGURE), prompted Keyhan and Munro to evaluate the efficacy of multimodal local anesthetic for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy without the use of any systemic agents except for preprocedural cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors (TABLE 2). Accordingly, they placed local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites to alleviate patient pain and improve procedural success in a spectrum of office-based hysteroscopic procedures.

Details of the trial

Procedures generally were performed using a continuous-flow sheath with an outside diameter of 5.5 mm and a 5 French operative channel for placement of operative instruments such as scissors, graspers, and sterilization microinserts. Normal saline or sterile water was used as the uterine distention medium, with gravity inflow assisted by pressure cuff, when necessary. Occasionally, a sheath system with an outside diameter of 6.5 mm was used, or an outside diameter of 9 mm for resectoscopic procedures using a bipolar radiofrequency resectoscope. When needed, cervical dilation was performed to accommodate the specific instrument used.

The impact of the multimodal, multisite anesthetic protocol was evaluated using contemporaneous patient reporting of numeric pain scores (worst pain experienced) that included anesthesia-related pain, procedure-related pain, and overall pain.

A total of 478 women underwent 535 procedures. A patient verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess the worst pain experienced. The overall mean (SD) procedure pain score was 3.7 (2.5). The mean score for patients undergoing diagnostic hysteroscopy was 3.2 (2.5), and it was 4.1 (2.5) for operative hysteroscopy (P<.001).

TABLE 3 shows the procedures performed under the anesthetic protocol. Pain associated with placement of anesthesia was similar for diagnostic and operative procedures (mean score, 2.7), but the mean overall pain scores for diagnostic procedures were about 1 unit less than for operative procedures, regardless of age or delivery history.

Complications were limited to 3 transient vasovagal episodes. Five procedures could not be completed because of intolerable pain or inability to access the uterine cavity. There was no difference in pain scores between menopausal and premeno-pausal women.

Malcolm G. Munro, MD, offers a protocol for pain relief during hysteroscopy

In this video, Malcolm G. Munro, MD, makes use of both topical and injectable lidocaine at 5 anatomic sites

Dr. Munro is Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Director of Gynecologic Services at Kaiser Permanente, Los Angeles Medical Center, in Los Angeles, California.

When placing anesthesia at multiple sites, allow time for onset of action

Keyhan and Munro demonstrated that successful completion of hysteroscopic procedures in the office environment can be achieved with acceptable levels of patient discomfort using a multimodal, multisite approach for preemptive placement of local anesthetic in the vagina, cervix, and endometrial cavity. They emphasize that the waiting time allotted for the onset of anesthesia is critical to the success of this approach. They also stress that no preprocedure oral sedative or narcotic is used with their approach. In addition, they note that the minimal discomfort experienced during placement of local anesthetic was overshadowed by general comfort during the wide spectrum of procedures performed.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The placement of preemptive local anesthesia at multiple anatomic sites facilitates diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy with an acceptable degree of patient comfort and successful completion of office procedures.

Music may reduce patient anxiety during hysteroscopy

Angioli R, De Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

Angioli and colleagues set out to address another factor that can impede patient comfort during office hysteroscopy—anxiety. Their randomized prospective trial is the only such trial evaluating the use of music to establish a calm and relaxing environment prior to office hysteroscopy for patients who are awake. Music supports an environment that “stimulates and maintains relaxation, well-being, and comfort and can be used as a self-management technique to reduce or control distress,” Angioli and colleagues write. The theory is that music distracts the patient by drawing her attention away from negative stimuli, thereby reducing pain, anxiety, and stress.

Details of the trial

A standardized visual analog scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess patient discomfort, and a State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; range, 20–80) also was given. Both tools were administered at baseline. The visual analog scale was measured again during the procedure, and the STAI was administered again after the procedure.

A hysteroscopic sheath with an outside diameter of 5 mm was used with a 5 French operative channel, and a vaginoscopic approach was used for each hysteroscopic procedure. A total of 372 women were enrolled and randomly allocated to either:

- music group (n = 185)

- no-music group (n = 187).

The surgical procedure was not completed in 15 patients (9 in the music group and 6 in the no-music group) because of stenosis of the cervix and/or excessive pain.

Women in the music group were allowed to select a playlist of classical, pop, jazz, or rock music that was played through a speaker system in the room. Of these patients, 50% preferred classical, 45% preferred pop, 5% chose jazz, and none selected rock music.

There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of preprocedure wait time, preprocedure scores on the visual analog scale or STAI, preprocedure vital signs, patient characteristics, type of procedure, or duration of the procedure. However, the music group had a lower visual analog score during the procedure and a lower postoperative STAI for diagnostic hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. The music group also had a statistically significant lower visual analog score for operative hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. In addition, the music group had a lower postoperative STAI score than the no-music group, but this difference was not statistically significant (TABLE 4).

Interestingly, in the music group, the STAI scores were lower after both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy when classical music was selected rather than pop music.

Anxiety and pain are highly correlated

Angioli and colleagues found that patients who listened to music intraoperatively had a lower perception of pain and less anxiety. In addition, systolic blood pressure and heart rate were significantly lower in the music group than the no-music group, implying that patients who listened to music experienced less physical stress during the procedure.

Angioli and colleagues also noted that the level of anxiety and perception of pain were highly correlated. Pain is not an emotionally neutral experience but is almost always accompanied by distress. Investigators concluded that “anxiety can enhance painful sensations at all levels of the nervous system, from the peripheral receptors to the cortical level.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Music is a useful complementary method to control patient anxiety and reduce the perception of pain during office hysteroscopy by creating a more relaxed and comfortable environment.

What are the risk factors for pain and discomfort during office hysteroscopy?

De Freitas FM, Sessa FV, Resende AD Jr, et al. Identifying predictors of unacceptable pain at office hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):586–591.

De Freitas and colleagues conducted their prospective observational study to identify predictors of unacceptable pain during diagnostic office hysteroscopy (with or without directed or curette endometrial biopsy) and at the time of discharge. They hoped that any identifiable causes of unacceptable pain could be addressed individually in future patients undergoing office hysteroscopy to reduce their level of discomfort.

Details of the trial

A total of 558 procedures were evaluated. Hysteroscopists had varying levels of experience, with some having performed fewer than 50 procedures and others having performed more than 500.

A verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess pain at the end of each procedure and at the time of discharge. Investigators considered a score of 7 or more at the time of the procedure and a score of 4 or more at the time of discharge to be unacceptable.

A diagnostic, single-channel hysteroscope with an outside diameter of 3.5 mm was used with normal saline (at room temperature), along with a gravity system with pressure established to maintain intrauterine pressure at approximately 110 mm Hg. All hysteroscopic procedures were performed using a vaginoscopic approach, and biopsies were obtained as clinically indicated. Any patients who reported cramping at discharge (ie, a verbal response scale score of 4 or more) were offered an oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Overall, the prevalence of unacceptable pain during office hysteroscopy was 32.3%. Experience of the hysteroscopist had a significant protective effect against pain. Longer procedures were significantly associated with unacceptable procedural pain.

The prevalence of unacceptable cramping at discharge was 28.6%. The risk of discomfort at discharge was significantly higher for women who reported dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea. Surgeon experience was significantly protective against unacceptable pain at discharge, and longer procedures were significantly associated with increased discomfort at discharge.

Dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia were significant predictors of pain at discharge

In this study, dysmenorrhea was a significant predictor of unacceptable pain at discharge, increasing the risk of unacceptable cramps by approximately threefold. Women who reported dyspareunia were nearly twice as likely to report unacceptable cramping at discharge.

Although a high level of expertise is not a prerequisite for office hysteroscopy, the skill and experience of the hysteroscopist, as well as shorter procedures, proved to be protective against procedural pain and discomfort at discharge but did not eliminate them altogether. Therefore, De Freitas and colleagues recommend that patients who can be identified as high-risk for procedural or discharge pain, such as women with dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia, should be offered preprocedure analgesia and/or anesthesia to reduce overall discomfort.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

If a patient reports dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia preoperatively, she may benefit from preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, or both, in an office setting.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Office hysteroscopy offers many benefits and is becoming more acceptable among patients and gynecologists for both diagnostic and operative procedures (TABLE 1). Despite its clear advantages, however, many gynecologists remain hesitant to perform in-office procedures out of fear that the patient, who is generally awake, will experience significant discomfort.

Certainly, pain and low patient tolerance of discomfort have been the primary limitations to widespread use of office hysteroscopy without anesthesia.1 Data on the use of anesthesia for office hysteroscopy—especially diagnostic procedures—historically have been inconsistent in regard to the reduction of patient discomfort.2

Bettocchi and Selvaggi first reported a vaginoscopic approach to diagnostic hysteroscopy to reduce the discomfort of the procedure, compared with the conventional approach. They did not place a vaginal speculum or tenaculum and, therefore, avoided placing local anesthetic into the cervix.3

A randomized controlled trial by Sagiv and colleagues found reduced pain during diagnostic hysteroscopy with vaginoscopy (VIDEO).4

In 2004, Bettocchi and colleagues reported nearly 5,000 operative hysteroscopic procedures performed with this technique (the “no-touch” technique) in an outpatient setting, demonstrating very high patient tolerance and a low degree of procedural pain. More than 90% of patients experienced little to no pain, except for those undergoing polypectomy when the polyps were larger than the diameter of the cervical os, as well as those who had anatomic abnormalities, with moderate discomfort reported by 33.2% and 12.7% of these women, respectively.5 These few patients may have benefited from anesthetic intervention for the procedure.

In a 2010 review of the literature on hysteroscopy without anesthesia, Cicinelli found that diagnostic hysteroscopy was more successful, with less patient discomfort, when smaller hysteroscopes were used (3.5 mm or smaller, including flexible lenses) and when the approach was vaginoscopic.1 Reduced pain with operative procedures was associated with a number of variables, including:

- increased surgeon experience

- smaller instrument size

- shorter duration of the procedure

- premenopausal status.

Variables associated with increased pain during operative procedures included:

- chronic pelvic pain

- menopausal status

- previous cesarean delivery

- significant anxiety.

In the review, Cicinelli noted that not all patients are likely to have a successful hysteroscopic procedure without the use of anesthesia or analgesia, regardless of the approach used.1

Only 1 randomized controlled trial explored the use of anesthesia (versus placebo) during operative hysteroscopy, and the authors found a benefit for preprocedural paracervical block using local anesthetic to reduce cervical pain.6

The success of diagnostic and operative hysteroscopic procedures with minimal and acceptable levels of patient discomfort in the office depends, therefore, on multiple factors. Procedural factors affecting the outcome of hysteroscopy include the size of the instrument used, the type and length of the procedure, the use of preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, and a vaginoscopic approach. The skill of the surgeon also affects the hysteroscopic experience and outcome. In addition, patient variables such as menopausal status, anatomic distortion (eg, cervical stenosis), and anxiety may adversely affect the patient’s experience.

In summary, it is possible for the gynecologist to appropriately accommodate any given patient and clinical scenario, keeping in mind that many patients will require a customized approach for ultimate success. In this article, I review 3 recent studies on office hysteroscopy, focusing on the reduction of procedural pain and anxiety. Because of the protective effect of a high degree of surgeon experience, it is important that we offer adequate education in hysteroscopy during residency and postgraduate courses.

Placement of local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites facilitates patient comfort during hysteroscopy

Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

In a 2010 review of randomized controlled trials of the use of local anesthesia versus placebo during hysteroscopy, data from several studies indicated a significant decrease in procedural pain when local anesthesia was given, while other studies found no difference.2 Most of the studies in that review evaluated a single site of anesthesia placement and focused on diagnostic hysteroscopy. The findings of that review, as well as the differential innervation of the uterine cervix and fundus (FIGURE), prompted Keyhan and Munro to evaluate the efficacy of multimodal local anesthetic for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy without the use of any systemic agents except for preprocedural cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors (TABLE 2). Accordingly, they placed local anesthetic at multiple anatomic sites to alleviate patient pain and improve procedural success in a spectrum of office-based hysteroscopic procedures.

Details of the trial

Procedures generally were performed using a continuous-flow sheath with an outside diameter of 5.5 mm and a 5 French operative channel for placement of operative instruments such as scissors, graspers, and sterilization microinserts. Normal saline or sterile water was used as the uterine distention medium, with gravity inflow assisted by pressure cuff, when necessary. Occasionally, a sheath system with an outside diameter of 6.5 mm was used, or an outside diameter of 9 mm for resectoscopic procedures using a bipolar radiofrequency resectoscope. When needed, cervical dilation was performed to accommodate the specific instrument used.

The impact of the multimodal, multisite anesthetic protocol was evaluated using contemporaneous patient reporting of numeric pain scores (worst pain experienced) that included anesthesia-related pain, procedure-related pain, and overall pain.

A total of 478 women underwent 535 procedures. A patient verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess the worst pain experienced. The overall mean (SD) procedure pain score was 3.7 (2.5). The mean score for patients undergoing diagnostic hysteroscopy was 3.2 (2.5), and it was 4.1 (2.5) for operative hysteroscopy (P<.001).

TABLE 3 shows the procedures performed under the anesthetic protocol. Pain associated with placement of anesthesia was similar for diagnostic and operative procedures (mean score, 2.7), but the mean overall pain scores for diagnostic procedures were about 1 unit less than for operative procedures, regardless of age or delivery history.

Complications were limited to 3 transient vasovagal episodes. Five procedures could not be completed because of intolerable pain or inability to access the uterine cavity. There was no difference in pain scores between menopausal and premeno-pausal women.

Malcolm G. Munro, MD, offers a protocol for pain relief during hysteroscopy

In this video, Malcolm G. Munro, MD, makes use of both topical and injectable lidocaine at 5 anatomic sites

Dr. Munro is Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Director of Gynecologic Services at Kaiser Permanente, Los Angeles Medical Center, in Los Angeles, California.

When placing anesthesia at multiple sites, allow time for onset of action

Keyhan and Munro demonstrated that successful completion of hysteroscopic procedures in the office environment can be achieved with acceptable levels of patient discomfort using a multimodal, multisite approach for preemptive placement of local anesthetic in the vagina, cervix, and endometrial cavity. They emphasize that the waiting time allotted for the onset of anesthesia is critical to the success of this approach. They also stress that no preprocedure oral sedative or narcotic is used with their approach. In addition, they note that the minimal discomfort experienced during placement of local anesthetic was overshadowed by general comfort during the wide spectrum of procedures performed.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The placement of preemptive local anesthesia at multiple anatomic sites facilitates diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy with an acceptable degree of patient comfort and successful completion of office procedures.

Music may reduce patient anxiety during hysteroscopy

Angioli R, De Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

Angioli and colleagues set out to address another factor that can impede patient comfort during office hysteroscopy—anxiety. Their randomized prospective trial is the only such trial evaluating the use of music to establish a calm and relaxing environment prior to office hysteroscopy for patients who are awake. Music supports an environment that “stimulates and maintains relaxation, well-being, and comfort and can be used as a self-management technique to reduce or control distress,” Angioli and colleagues write. The theory is that music distracts the patient by drawing her attention away from negative stimuli, thereby reducing pain, anxiety, and stress.

Details of the trial

A standardized visual analog scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess patient discomfort, and a State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; range, 20–80) also was given. Both tools were administered at baseline. The visual analog scale was measured again during the procedure, and the STAI was administered again after the procedure.

A hysteroscopic sheath with an outside diameter of 5 mm was used with a 5 French operative channel, and a vaginoscopic approach was used for each hysteroscopic procedure. A total of 372 women were enrolled and randomly allocated to either:

- music group (n = 185)

- no-music group (n = 187).

The surgical procedure was not completed in 15 patients (9 in the music group and 6 in the no-music group) because of stenosis of the cervix and/or excessive pain.

Women in the music group were allowed to select a playlist of classical, pop, jazz, or rock music that was played through a speaker system in the room. Of these patients, 50% preferred classical, 45% preferred pop, 5% chose jazz, and none selected rock music.

There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of preprocedure wait time, preprocedure scores on the visual analog scale or STAI, preprocedure vital signs, patient characteristics, type of procedure, or duration of the procedure. However, the music group had a lower visual analog score during the procedure and a lower postoperative STAI for diagnostic hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. The music group also had a statistically significant lower visual analog score for operative hysteroscopy than the no-music group did. In addition, the music group had a lower postoperative STAI score than the no-music group, but this difference was not statistically significant (TABLE 4).

Interestingly, in the music group, the STAI scores were lower after both diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy when classical music was selected rather than pop music.

Anxiety and pain are highly correlated

Angioli and colleagues found that patients who listened to music intraoperatively had a lower perception of pain and less anxiety. In addition, systolic blood pressure and heart rate were significantly lower in the music group than the no-music group, implying that patients who listened to music experienced less physical stress during the procedure.

Angioli and colleagues also noted that the level of anxiety and perception of pain were highly correlated. Pain is not an emotionally neutral experience but is almost always accompanied by distress. Investigators concluded that “anxiety can enhance painful sensations at all levels of the nervous system, from the peripheral receptors to the cortical level.”

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Music is a useful complementary method to control patient anxiety and reduce the perception of pain during office hysteroscopy by creating a more relaxed and comfortable environment.

What are the risk factors for pain and discomfort during office hysteroscopy?

De Freitas FM, Sessa FV, Resende AD Jr, et al. Identifying predictors of unacceptable pain at office hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):586–591.

De Freitas and colleagues conducted their prospective observational study to identify predictors of unacceptable pain during diagnostic office hysteroscopy (with or without directed or curette endometrial biopsy) and at the time of discharge. They hoped that any identifiable causes of unacceptable pain could be addressed individually in future patients undergoing office hysteroscopy to reduce their level of discomfort.

Details of the trial

A total of 558 procedures were evaluated. Hysteroscopists had varying levels of experience, with some having performed fewer than 50 procedures and others having performed more than 500.

A verbal response scale (range, 0–10) was used to assess pain at the end of each procedure and at the time of discharge. Investigators considered a score of 7 or more at the time of the procedure and a score of 4 or more at the time of discharge to be unacceptable.

A diagnostic, single-channel hysteroscope with an outside diameter of 3.5 mm was used with normal saline (at room temperature), along with a gravity system with pressure established to maintain intrauterine pressure at approximately 110 mm Hg. All hysteroscopic procedures were performed using a vaginoscopic approach, and biopsies were obtained as clinically indicated. Any patients who reported cramping at discharge (ie, a verbal response scale score of 4 or more) were offered an oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Overall, the prevalence of unacceptable pain during office hysteroscopy was 32.3%. Experience of the hysteroscopist had a significant protective effect against pain. Longer procedures were significantly associated with unacceptable procedural pain.

The prevalence of unacceptable cramping at discharge was 28.6%. The risk of discomfort at discharge was significantly higher for women who reported dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea. Surgeon experience was significantly protective against unacceptable pain at discharge, and longer procedures were significantly associated with increased discomfort at discharge.

Dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia were significant predictors of pain at discharge

In this study, dysmenorrhea was a significant predictor of unacceptable pain at discharge, increasing the risk of unacceptable cramps by approximately threefold. Women who reported dyspareunia were nearly twice as likely to report unacceptable cramping at discharge.

Although a high level of expertise is not a prerequisite for office hysteroscopy, the skill and experience of the hysteroscopist, as well as shorter procedures, proved to be protective against procedural pain and discomfort at discharge but did not eliminate them altogether. Therefore, De Freitas and colleagues recommend that patients who can be identified as high-risk for procedural or discharge pain, such as women with dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia, should be offered preprocedure analgesia and/or anesthesia to reduce overall discomfort.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

If a patient reports dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia preoperatively, she may benefit from preprocedure anesthesia or analgesia, or both, in an office setting.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):703–708.

2. Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

3. Bettocchi S, Selvaggi L. A vaginoscopic approach to reduce the pain of office hysteroscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(2):255–258.

4. Sagiv R, Sadan O, Boaz M, et al. A new approach to office hysteroscopy compared with traditional hysteroscopy. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):387–392.

5.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Nappi L, et al. Operative office hysteroscopy without anesthesia: analysis of 4,863 cases performed with mechanical instruments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(1):59–61.

6. Chudnoff S, Einstein M, Levie M. Paracervical block efficacy in office hysteroscopic sterilization. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):26–34.

7. Garcia AL. Stop performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2013;25(6):44–48.

8. Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

9. Angioli R, de Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

1. Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):703–708.

2. Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

3. Bettocchi S, Selvaggi L. A vaginoscopic approach to reduce the pain of office hysteroscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(2):255–258.

4. Sagiv R, Sadan O, Boaz M, et al. A new approach to office hysteroscopy compared with traditional hysteroscopy. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):387–392.

5.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Nappi L, et al. Operative office hysteroscopy without anesthesia: analysis of 4,863 cases performed with mechanical instruments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(1):59–61.

6. Chudnoff S, Einstein M, Levie M. Paracervical block efficacy in office hysteroscopic sterilization. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):26–34.

7. Garcia AL. Stop performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2013;25(6):44–48.

8. Keyhan S, Munro MG. Office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy using local anesthesia only: an analysis of patient reported pain and other procedural outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):791–798.

9. Angioli R, de Cicco Nardone C, Plotti F, et al. Use of music to reduce anxiety during office hysteroscopy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):454–459.

In this Article

— Innervation of the uterus

— Pain scores associated with specific hysteroscopic procedures