User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

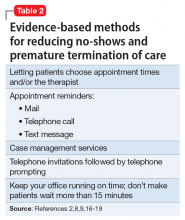

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

1. Adler LM, Yamamoto J, Goin M. Failed psychiatric clinic appointments. Relationship to social class. Calif Med. 1963;99:388-392.

2. Buppert C. How to deal with missed appointments. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):207-208.

3. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Psychiatric-Shortage_National-Council-.pdf. Published March 28, 2017. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Legal & Regulatory Affairs staff. Practitioner pointer: how to handle late and missed appointments. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/11-06/late-missed-appoitments.aspx. Published November 6, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2017.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MLN Matters Number: MM5613. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM5613.pdf. Updated November 12, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2017.

6. MacCutcheon M. Why I charge for late cancellations and no-shows to therapy. http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/why-i-charge-for-late-cancellations-no-shows-to-therapy-0921164. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed April 6, 2017.

7. Kalman TP, Goldstein MA. Satisfaction of Manhattan psychiatrists with private practice: assessing the impact of managed care. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430759_4. Accessed April 6, 2017.

8. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-434.

9. Long J, Sakauye K, Chisty K, et al. The empty chair appointment. SAGE Open. 2016;6:1-5.

10. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611.

11. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160-165.

13. Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, et al. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014120.

14. Binnie J, Boden Z. Non-attendance at psychological therapy appointments. Mental Health Rev J. 2016;21(3):231-248.

15. Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Dudek D. Various ways of understanding compliance: a psychiatrist’s view. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2011;13(3):49-55.

16. Boland B, Burnett F. Optimising outpatient efficiency – development of an innovative ‘Did Not Attend’ management approach. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(3):217-219.

17. Pennington D, Hodgson J. Non‐attendance and invitation methods within a CBT service. Mental Health Rev J. 2012;17(3):145-151.

18. Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, et al. Text message reminders of appointments: a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):161-168.

19. Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, et al. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):928-939.

20. Gore AG, Grossman EL, Martin L, et al. Physicians, surgeons, and other healers. In: American Jurisprudence. 2nd ed, §130. Eagan, MN: West Publishing; 2017:61.

21. Ohio Administrative Code §4731-27-02.

22. Lowery v Miller, 157 Wis 2d 503, 460 N.W. 2d 446 (Wis App 1990).

23. Brockway LH. Terminating patient relationships: how to dismiss without abandoning. TMLT. https://www.tmlt.org/tmlt/tmlt-resources/newscenter/blog/2009/Terminating-patient-relationships.html. Published June 19, 2009. Accessed April 3, 2017.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

1. Adler LM, Yamamoto J, Goin M. Failed psychiatric clinic appointments. Relationship to social class. Calif Med. 1963;99:388-392.

2. Buppert C. How to deal with missed appointments. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):207-208.

3. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Psychiatric-Shortage_National-Council-.pdf. Published March 28, 2017. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Legal & Regulatory Affairs staff. Practitioner pointer: how to handle late and missed appointments. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/11-06/late-missed-appoitments.aspx. Published November 6, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2017.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MLN Matters Number: MM5613. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM5613.pdf. Updated November 12, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2017.

6. MacCutcheon M. Why I charge for late cancellations and no-shows to therapy. http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/why-i-charge-for-late-cancellations-no-shows-to-therapy-0921164. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed April 6, 2017.

7. Kalman TP, Goldstein MA. Satisfaction of Manhattan psychiatrists with private practice: assessing the impact of managed care. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430759_4. Accessed April 6, 2017.

8. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-434.

9. Long J, Sakauye K, Chisty K, et al. The empty chair appointment. SAGE Open. 2016;6:1-5.

10. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611.

11. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160-165.

13. Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, et al. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014120.

14. Binnie J, Boden Z. Non-attendance at psychological therapy appointments. Mental Health Rev J. 2016;21(3):231-248.

15. Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Dudek D. Various ways of understanding compliance: a psychiatrist’s view. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2011;13(3):49-55.

16. Boland B, Burnett F. Optimising outpatient efficiency – development of an innovative ‘Did Not Attend’ management approach. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(3):217-219.

17. Pennington D, Hodgson J. Non‐attendance and invitation methods within a CBT service. Mental Health Rev J. 2012;17(3):145-151.

18. Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, et al. Text message reminders of appointments: a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):161-168.

19. Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, et al. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):928-939.

20. Gore AG, Grossman EL, Martin L, et al. Physicians, surgeons, and other healers. In: American Jurisprudence. 2nd ed, §130. Eagan, MN: West Publishing; 2017:61.

21. Ohio Administrative Code §4731-27-02.

22. Lowery v Miller, 157 Wis 2d 503, 460 N.W. 2d 446 (Wis App 1990).

23. Brockway LH. Terminating patient relationships: how to dismiss without abandoning. TMLT. https://www.tmlt.org/tmlt/tmlt-resources/newscenter/blog/2009/Terminating-patient-relationships.html. Published June 19, 2009. Accessed April 3, 2017.

1. Adler LM, Yamamoto J, Goin M. Failed psychiatric clinic appointments. Relationship to social class. Calif Med. 1963;99:388-392.

2. Buppert C. How to deal with missed appointments. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):207-208.

3. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Psychiatric-Shortage_National-Council-.pdf. Published March 28, 2017. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Legal & Regulatory Affairs staff. Practitioner pointer: how to handle late and missed appointments. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/11-06/late-missed-appoitments.aspx. Published November 6, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2017.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MLN Matters Number: MM5613. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM5613.pdf. Updated November 12, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2017.

6. MacCutcheon M. Why I charge for late cancellations and no-shows to therapy. http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/why-i-charge-for-late-cancellations-no-shows-to-therapy-0921164. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed April 6, 2017.

7. Kalman TP, Goldstein MA. Satisfaction of Manhattan psychiatrists with private practice: assessing the impact of managed care. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430759_4. Accessed April 6, 2017.

8. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-434.

9. Long J, Sakauye K, Chisty K, et al. The empty chair appointment. SAGE Open. 2016;6:1-5.

10. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611.

11. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160-165.

13. Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, et al. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014120.

14. Binnie J, Boden Z. Non-attendance at psychological therapy appointments. Mental Health Rev J. 2016;21(3):231-248.

15. Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Dudek D. Various ways of understanding compliance: a psychiatrist’s view. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2011;13(3):49-55.

16. Boland B, Burnett F. Optimising outpatient efficiency – development of an innovative ‘Did Not Attend’ management approach. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(3):217-219.

17. Pennington D, Hodgson J. Non‐attendance and invitation methods within a CBT service. Mental Health Rev J. 2012;17(3):145-151.

18. Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, et al. Text message reminders of appointments: a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):161-168.

19. Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, et al. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):928-939.

20. Gore AG, Grossman EL, Martin L, et al. Physicians, surgeons, and other healers. In: American Jurisprudence. 2nd ed, §130. Eagan, MN: West Publishing; 2017:61.

21. Ohio Administrative Code §4731-27-02.

22. Lowery v Miller, 157 Wis 2d 503, 460 N.W. 2d 446 (Wis App 1990).

23. Brockway LH. Terminating patient relationships: how to dismiss without abandoning. TMLT. https://www.tmlt.org/tmlt/tmlt-resources/newscenter/blog/2009/Terminating-patient-relationships.html. Published June 19, 2009. Accessed April 3, 2017.