User login

CHICAGO – Breathlessness typically results in hospital admission for patients with heart failure, but peripheral edema is what prolongs their stay, according to Dr. John G.F. Cleland.

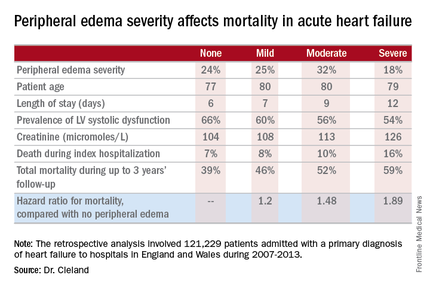

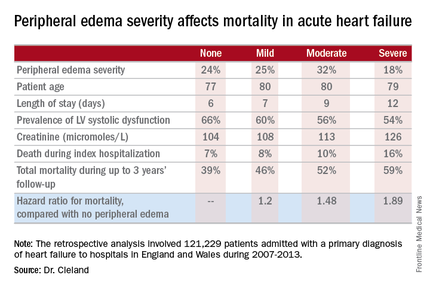

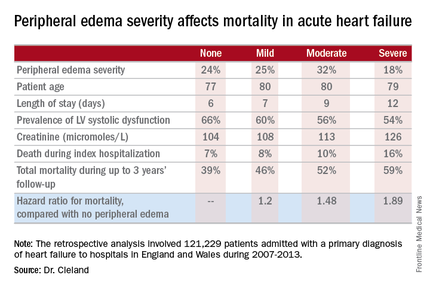

Moreover, it’s not only hospital length of stay that climbs with increasing severity of peripheral edema on admission. So does mortality, both during the index admission and long term, Dr. Cleland reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented a retrospective analysis of 121,229 patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure to more than 90% of the hospitals in England and Wales during 2007-2013.

“It turns out that the majority of patients we’re seeing admitted with heart failure at U.K. hospitals are not admitted because of severe breathlessness at rest; they’re admitted for increasing fluid retention. They have lots of peripheral edema, which is actually associated with bad outcome. The patients who are very breathless tend to have the better outcome because they have left heart failure. The ones who are full of peripheral edema have more renal dysfunction and anemia, and they’re more likely to have right heart failure,” said Dr. Cleland, professor of cardiology at Imperial College London.

“I’m not saying the breathless group isn’t a target, but this group with peripheral edema is a bigger target – and we’re not designing trials to address their problems,” he added.

Compared with patients with no peripheral edema on hospital admission, the risk of mortality during that hospitalization and up to 3 years of subsequent follow-up was increased 1.2-fold in those with mild peripheral edema, 1.48-fold with moderate peripheral edema, and 1.89-fold in those with severe peripheral edema.

“We’re designing all the big clinical trials in acute heart failure to capture what I regard as neither fish nor fowl. They’re recruiting patients 6-12 hours after admission for acute heart failure. But by that point they’ve pretty well responded to their intravenous diuretics, and we’re just catching the tail end of their breathlessness. They’re not an emergency. The problem is really their peripheral edema, and that’s a day 2/day 3 problem. The first 6 hours of care really isn’t relevant to this group,” according to the internationally renowned heart failure researcher.

Indeed, he said he’d like to see the term “acute heart failure” laid to rest.

“If you think of acute decompensated heart failure, you think of patients wearing an oxygen mask coming in by an ambulance with blue lights flashing, and it’s an emergency. We need to move the mind-set. We shouldn’t call it acute heart failure at all, we should start talking about hospitalized heart failure, of which some is acute but much of it is subacute in people who have been deteriorating over several weeks and have just gotten to the point where they’re not coping at home anymore. They call a taxi or a friend who takes them to the hospital. Then they take a wheelchair from the taxi to the ER, but they don’t really need an ER at all,” Dr. Cleland said.

Many of these patients could be redirected to a different sort of facility at great cost savings, he added.

“In the United Kingdom and I think in the States, we’re now talking about furosemide lounges where, rather than admit the patient, you can bring them up as a day case, give them intravenous therapy, then [have them] go home at night, perhaps coming back for 3 or 4 days if needed. People are also now looking at home infusion services, and there’s a nice device for giving subcutaneous doses of furosemide as well,” the cardiologist said.

Apart from diuretics, there really aren’t any effective medications at present for peripheral edema in heart failure. But there are novel investigational agents worthy of evaluation, according to Dr. Cleland, including drugs aimed at improving mitochondrial function, agents that inhibit channels that allow edema to gather, and iron therapy.

The study was supported by the British Society for Heart Failure and the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Dr. Cleland reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Breathlessness typically results in hospital admission for patients with heart failure, but peripheral edema is what prolongs their stay, according to Dr. John G.F. Cleland.

Moreover, it’s not only hospital length of stay that climbs with increasing severity of peripheral edema on admission. So does mortality, both during the index admission and long term, Dr. Cleland reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented a retrospective analysis of 121,229 patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure to more than 90% of the hospitals in England and Wales during 2007-2013.

“It turns out that the majority of patients we’re seeing admitted with heart failure at U.K. hospitals are not admitted because of severe breathlessness at rest; they’re admitted for increasing fluid retention. They have lots of peripheral edema, which is actually associated with bad outcome. The patients who are very breathless tend to have the better outcome because they have left heart failure. The ones who are full of peripheral edema have more renal dysfunction and anemia, and they’re more likely to have right heart failure,” said Dr. Cleland, professor of cardiology at Imperial College London.

“I’m not saying the breathless group isn’t a target, but this group with peripheral edema is a bigger target – and we’re not designing trials to address their problems,” he added.

Compared with patients with no peripheral edema on hospital admission, the risk of mortality during that hospitalization and up to 3 years of subsequent follow-up was increased 1.2-fold in those with mild peripheral edema, 1.48-fold with moderate peripheral edema, and 1.89-fold in those with severe peripheral edema.

“We’re designing all the big clinical trials in acute heart failure to capture what I regard as neither fish nor fowl. They’re recruiting patients 6-12 hours after admission for acute heart failure. But by that point they’ve pretty well responded to their intravenous diuretics, and we’re just catching the tail end of their breathlessness. They’re not an emergency. The problem is really their peripheral edema, and that’s a day 2/day 3 problem. The first 6 hours of care really isn’t relevant to this group,” according to the internationally renowned heart failure researcher.

Indeed, he said he’d like to see the term “acute heart failure” laid to rest.

“If you think of acute decompensated heart failure, you think of patients wearing an oxygen mask coming in by an ambulance with blue lights flashing, and it’s an emergency. We need to move the mind-set. We shouldn’t call it acute heart failure at all, we should start talking about hospitalized heart failure, of which some is acute but much of it is subacute in people who have been deteriorating over several weeks and have just gotten to the point where they’re not coping at home anymore. They call a taxi or a friend who takes them to the hospital. Then they take a wheelchair from the taxi to the ER, but they don’t really need an ER at all,” Dr. Cleland said.

Many of these patients could be redirected to a different sort of facility at great cost savings, he added.

“In the United Kingdom and I think in the States, we’re now talking about furosemide lounges where, rather than admit the patient, you can bring them up as a day case, give them intravenous therapy, then [have them] go home at night, perhaps coming back for 3 or 4 days if needed. People are also now looking at home infusion services, and there’s a nice device for giving subcutaneous doses of furosemide as well,” the cardiologist said.

Apart from diuretics, there really aren’t any effective medications at present for peripheral edema in heart failure. But there are novel investigational agents worthy of evaluation, according to Dr. Cleland, including drugs aimed at improving mitochondrial function, agents that inhibit channels that allow edema to gather, and iron therapy.

The study was supported by the British Society for Heart Failure and the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Dr. Cleland reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Breathlessness typically results in hospital admission for patients with heart failure, but peripheral edema is what prolongs their stay, according to Dr. John G.F. Cleland.

Moreover, it’s not only hospital length of stay that climbs with increasing severity of peripheral edema on admission. So does mortality, both during the index admission and long term, Dr. Cleland reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented a retrospective analysis of 121,229 patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure to more than 90% of the hospitals in England and Wales during 2007-2013.

“It turns out that the majority of patients we’re seeing admitted with heart failure at U.K. hospitals are not admitted because of severe breathlessness at rest; they’re admitted for increasing fluid retention. They have lots of peripheral edema, which is actually associated with bad outcome. The patients who are very breathless tend to have the better outcome because they have left heart failure. The ones who are full of peripheral edema have more renal dysfunction and anemia, and they’re more likely to have right heart failure,” said Dr. Cleland, professor of cardiology at Imperial College London.

“I’m not saying the breathless group isn’t a target, but this group with peripheral edema is a bigger target – and we’re not designing trials to address their problems,” he added.

Compared with patients with no peripheral edema on hospital admission, the risk of mortality during that hospitalization and up to 3 years of subsequent follow-up was increased 1.2-fold in those with mild peripheral edema, 1.48-fold with moderate peripheral edema, and 1.89-fold in those with severe peripheral edema.

“We’re designing all the big clinical trials in acute heart failure to capture what I regard as neither fish nor fowl. They’re recruiting patients 6-12 hours after admission for acute heart failure. But by that point they’ve pretty well responded to their intravenous diuretics, and we’re just catching the tail end of their breathlessness. They’re not an emergency. The problem is really their peripheral edema, and that’s a day 2/day 3 problem. The first 6 hours of care really isn’t relevant to this group,” according to the internationally renowned heart failure researcher.

Indeed, he said he’d like to see the term “acute heart failure” laid to rest.

“If you think of acute decompensated heart failure, you think of patients wearing an oxygen mask coming in by an ambulance with blue lights flashing, and it’s an emergency. We need to move the mind-set. We shouldn’t call it acute heart failure at all, we should start talking about hospitalized heart failure, of which some is acute but much of it is subacute in people who have been deteriorating over several weeks and have just gotten to the point where they’re not coping at home anymore. They call a taxi or a friend who takes them to the hospital. Then they take a wheelchair from the taxi to the ER, but they don’t really need an ER at all,” Dr. Cleland said.

Many of these patients could be redirected to a different sort of facility at great cost savings, he added.

“In the United Kingdom and I think in the States, we’re now talking about furosemide lounges where, rather than admit the patient, you can bring them up as a day case, give them intravenous therapy, then [have them] go home at night, perhaps coming back for 3 or 4 days if needed. People are also now looking at home infusion services, and there’s a nice device for giving subcutaneous doses of furosemide as well,” the cardiologist said.

Apart from diuretics, there really aren’t any effective medications at present for peripheral edema in heart failure. But there are novel investigational agents worthy of evaluation, according to Dr. Cleland, including drugs aimed at improving mitochondrial function, agents that inhibit channels that allow edema to gather, and iron therapy.

The study was supported by the British Society for Heart Failure and the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Dr. Cleland reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Leg swelling warrants greater attention in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality was more than twice as great in patients admitted for acute heart failure with severe peripheral edema, compared with no leg swelling.

Data source: A retrospective study of more than 121,000 patients hospitalized for acute heart failure in England and Wales.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the British Society for Heart Failure and the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.