User login

Should you prescribe a stimulant to treat attention and hyperactivity problems in teenagers and adults with a history of substance abuse? Evidence suggests that using a stimulant to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may place such patients at risk for stimulant abuse or for relapse into abuse of other substances. But a stimulant may be the only option for patients whose ADHD symptoms do not respond to alternate medications, such as antidepressants.

Growing numbers of adults are being treated for ADHD. Because substance abuse problems are common in adults with ADHD (Box 1 ),1-3 prescribing an antidepressant instead of a stimulant in some cases may be prudent. Consider the following factors when choosing ADHD therapy for patients with a history of substance abuse.

Prevalence of stimulant use and abuse

In the United States, more than 95% of medications prescribed for children and adults with ADHD are stimulants—usually methylphenidate.4 Stimulant use has increased as more children and adults are diagnosed with ADHD. Methylphenidate prescriptions increased five-fold from 1990 to 1995.5 Visits to psychiatrists and physicians that included stimulant prescriptions grew from 570,000 to 2.86 million from 1985 to 1994, with most of that increase occurring during visits to primary care and other physicians.6

When used as prescribed, methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating most children and adults with ADHD. Methylphenidate’s pharmacologic properties, however, are similar to those of amphetamines and cocaine (Box 2, Figure 1),7,8 which is why methylphenidate is a schedule-II controlled substance.

Published data. Fifteen reports of methylphenidate abuse were published in the medical literature between 1960 and 1999,7 but little is known about the prevalence of stimulant abuse among patients with ADHD. Banov and colleagues recently published what may be the only data available, when they reported that 3 of 37 (8%) patients abused the stimulants they were prescribed for ADHD.9 The three patients who abused stimulants had histories of drug and alcohol abuse at study entry. In all three cases, stimulant abuse did not develop immediately but became apparent within 6 months after the study began.

In a study of 651 students ages 11 to 18 in Wisconsin and Minnesota, more than one-third of those taking stimulants reported being asked to sell or trade their medications. More than one-half of those not taking ADHD medications said they knew someone who sold or gave away his or her medication.10

Stimulant theft, recreational use. Methylphenidate has been identified as the third most abused prescribed substance in the United States.11 It was the 10th most frequently stolen controlled drug from pharmacies between 1990 and 1995, and 700,000 dosage units were reported stolen in 1996 and 1997.12

As many as 50% of adults with ADHD have substance abuse problems (including alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana), and as many as 30% have antisocial personality disorder (with increased potential for drug-seeking behaviors).1 Compared with the general population, persons with ADHD have an earlier onset of substance abuse that is less responsive to treatment and more likely to progress from alcohol to other drugs.2

The elevated risk of substance abuse in ADHD may be related to a subtle lack of response to normal positive and negative reinforcements. Hunt has outlined four neurobehavioral deficits that define ADHD.3 Besides inattention, hyperarousal, and impulsiveness, he proposes that persons with ADHD have a reward system deficit. They may gravitate toward substance abuse because drugs, alcohol, and nicotine provide stronger rewards than life’s more subtle social interactions.

The popular media have reported recreational use of methylphenidate—with street names such as “R-Ball” and “Vitamin R”—among teens and college students.13 Illegal stimulants are perceived to be easily accessible on college campuses, but no data have been reported.

The use of stimulant medication for ADHD patients with substance abuse problems remains controversial. For such patients, this author reserves stimulant medication for those:

- whose ADHD symptoms have not responded adequately to alternate treatments

- who have been reliable with prescription medications

- and whose functional level is seriously impaired by their ADHD.

Antidepressants vs. stimulants

Although few well-designed controlled studies have been published, four antidepressants appear to be reasonably equivalent in effectiveness for adults with ADHD and do not carry potential for stimulant abuse.14

Desipraime, bupropion, venlafaxine, and the experimental drug atomoxetine (Table 1) all increase norepinephrine at the synapse by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake. Though dopamine has traditionally been considered the neurotransmitter of choice for ADHD treatment, norepinephrine may be equally potent.

Impulse control center. Several lines of research have recently established a connection between the prefrontal cortex, norepinephrine, and ADHD.15 This evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex plays a major role in inhibiting impulses and responses to distractions:

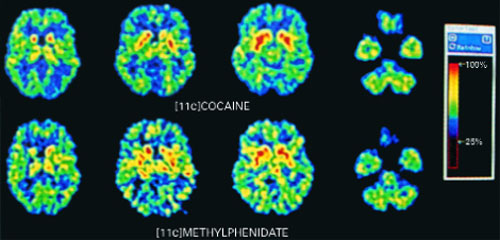

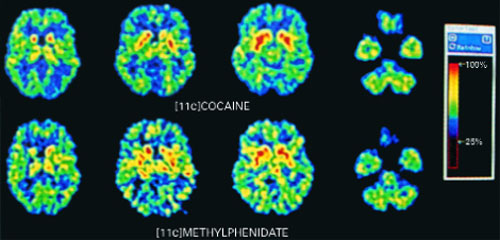

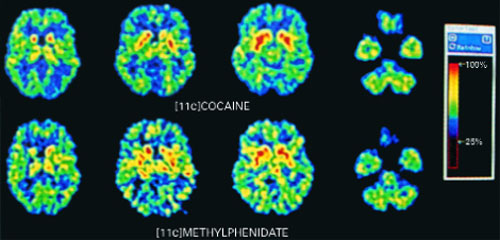

Figure 1

PET scans of the brain using carbon 11 (11C)-labeled cocaine and methylphenidate HCl show similar distributions in the striatium when the drugs are administered intravenously.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

Stimulants are classified as schedule-II drugs because they produce powerful reinforcing effects by increasing synaptic dopamine.7 Positron-emission tomography (PET) scans using carbon labeling have shown similar distributions of methylphenidate and cocaine in the brain (Figure 1).8 When administered intravenously, both drugs occupy the same receptors in the striatum and produce a “high” that parallels rapid neuronal uptake. Methylphenidate and cocaine similarly increase stimulation of the postsynaptic neuron by blocking the dopamine reuptake pump (dopamine transporter).

How a substance gets to the brain’s euphoric receptors greatly affects its addictive properties. Delivery systems with rapid onset—smoking, “snorting,” or IV injection—have much greater ability to produce a “high” than do oral or transdermal routes. The greater the “high,” the greater the potential for abuse.

Because methylphenidate is prescribed for oral use, the potential for abuse is minimal. However, we need to be extremely cautious when giving methylphenidate or similar stimulant medications to patients who have shown they are unable to control their abuse of other substances.

Stimulants can also re-ignite a dormant substance abuse problem. Though little has been written about this in the medical literature, Elizabeth Wurtzel, author of the controversial Prozac Nation, chronicles the resumption of her cocaine abuse in More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction. She contends that after her doctor added methylphenidate to augment treatment of partially remitting depression, she began abusing it and eventually was using 40 tablets per day before slipping back into cocaine dependence.

- Patients with prefrontal cortex deficits can have problems with inattention and poor impulse control.

- Patients with ADHD have frontal lobe impairments, as neuropsychological testing and imaging studies have shown.

- Norepinephrine neurons, with cell bodies in the locus coeruleus, have projections that terminate in the prefrontal cortex.

- Agents with norepinephrine activity, but without mood-altering properties (e.g., clonidine), have been shown to improve ADHD symptoms.

Table 1

ADHD IN ADULTS: ANTIDEPRESSANT DOSAGES AND SIDE EFFECTS

| Medication | Class | Effective dosage | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desipramine | Tricyclic | 100 to 200 mg/d | Sedation, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, prolonged cardiac conduction time; may be lethal in overdose |

| Bupropion SR | Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 150 mg bid to 200 mg bid | Headaches, insomnia, agitation, increased risk of seizures |

| Venlafaxine XR | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 75 to 225 mg/d | Nausea, sexual side effects, agitation, increased blood pressure at higher dosages |

| Atomoxetine* | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | To be determined | To be determined |

| * Investigational agent; not FDA-approved | |||

Additional evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex has projections back to the locus coeruleus, which may explain the relationship between the two areas. It may be that the brain’s higher-functioning areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, provide intelligent screening of impulses from the brain’s older areas, such as the locus coeruleus. Therefore, increased prefrontal cortex activity may modulate some impulses that ADHD patients cannot control otherwise.

No ‘high’ with antidepressants. Patients with ADHD who have experienced the powerful effects of street drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or even alcohol may report that antidepressants do not provide the effect they desire. It is difficult to know if these patients are reporting a lack of benefit or simply the absence of a euphoric “high” they are used to experiencing with substances of abuse. The newer antidepressants do not activate the brain’s euphoric receptors to an appreciable degree.

Patients who take stimulants as prescribed also do not report a “high” but can detect the medication’s presence and absence. Most do not crave this feeling, but substance abusers tend to like it. A patient recently told me he didn’t think stimulants improved his ADHD, but said, “I just liked the way they made me feel.”

Desipramine

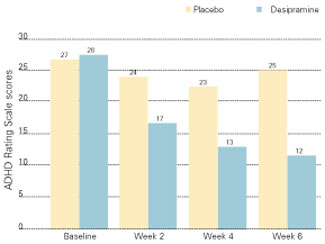

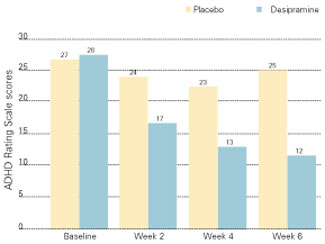

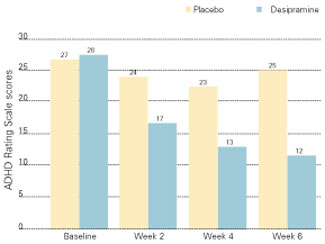

The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine is a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is effective in treating ADHD in children and adults. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with ADHD, subjects receiving desipramine showed robust improvement in symptom scores on the ADHD Rating Scale,16 compared with those receiving the placebo (Figure 2).17

During the 6-week trial, 41 adults with ADHD received desipramine, 200 mg/d, or a placebo. Those receiving desipramine showed significant improvement in 12 of 14 ADHD symptoms and less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness, whereas those receiving the placebo showed no improvement. According to the study criteria, 68% of those who received desipramine and none who received the placebo were considered positive responders.

Though no head-to-head studies have compared desipramine with methylphenidate, the same researchers conducted a similar placebo-controlled study with methylphenidate. The 6-week symptom score on the ADHD Rating Scale was 12.5 for methylphenidate, compared with a score of 12 for desipramine.18

Recommendation. Desipramine may be the most effective of the antidepressant treatments for patients with ADHD. Because of its side effects, however, it is not this author’s first choice and is usually reserved for patients whose symptoms fail to respond to other antidepressants. Desipramine can cause sedation, dry mouth, and constipation, which are related to blockade of adrenergic, histamine, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. It also can be lethal in overdose.

Some substance abusers lose confidence in a medication that they cannot feel working. The side effects of desipramine, which can be intolerable for some patients, can reassure others with a history of substance abuse that they are being medicated.

Bupropion

Bupropion is a unique antidepressant that inhibits the presynaptic reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. Open-label studies demonstrate good responses to bupropion by adults with ADHD. One placebo-controlled, double-blind study found improved ADHD symptoms in 76% of patients receiving bupropion SR, compared with 37% of those receiving a placebo; the difference was statistically significant.19

Figure 2 IMPROVED ADHD SYMPTOMS WITH DESIPRAMINE

Adults with ADHD who received desipramine, 200 mg/d, in a double-blind trial showed significantly less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness after 6 weeks of therapy than a control group that received a placebo.

Source: Adapted with permission from Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.Another study of adults with ADHD compared bupropion SR to methylphenidate and a placebo.20 Using a primary outcome of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, response rates were 64% for bupropion SR, 50% for methylphenidate, and 27% for the placebo. The difference in response rates between the two agents was not statistically significant (p = 0.14).

Recommendation. The risk of seizures with bupropion is about 1 in 1,000. Therefore, bupropion should not be given to patients with a seizure disorder or to those with conditions that alter the seizure threshold (e.g., eating disorders, recent head trauma, or benzodiazepine withdrawal).21

This author uses bupropion as first-line treatment for appropriate patients with ADHD and a substance abuse history. Bupropion’s mild benefit with smoking cessation may provide some crossover effect for other substances of abuse. The low incidence of sexual side effects is another benefit. Drawbacks include twice-daily dosing and lack of a robust effect on attention and concentration.

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine is a potent inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, a moderate inhibitor of norepinephrine, and a mild inhibitor of dopamine. Venlafaxine has displayed response rates similar to those of desipramine and bupropion in open-label studies in adults with ADHD,14 but no placebo-controlled studies exist.

As noted above, these antidepressants are believed to improve ADHD symptoms by making norepinephrine more available at the synapse. Hypothetically, then, one would need to administer venlafaxine at dosages that adequately inhibit the norepinephrine reuptake receptor. Venlafaxine XR, 150 mg/d, provides significant norepinephrine activity, according to several lines of evidence.

Recently, Upadhyaya et al reported the use of venlafaxine in one of the few treatment studies of patients with ADHD and comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse. In an open-label trial, 10 subjects received venlafaxine, up to 300 mg/d, along with psychotherapy and attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The nine who completed 4 weeks of treatment showed significantly improved ADHD symptoms and decreased alcohol craving.22

Recommendation. Venlafaxine is this author’s second choice for patients with ADHD and substance abuse problems. Sexual side effects that some patients experience with venlafaxine can limit its use. Some clinicians are concerned about increases in blood pressure associated with venlafaxine, although significant changes do not seem to occur at dosages below 300 mg/d.23

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is an investigational antidepressant in phase-III trials as a treatment for ADHD. Evidence shows atomoxetine to be a potent inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter, with minimal affinity for other neurotransmitter receptors. Initial studies suggest that atomoxetine is effective for adults and children with ADHD:

- In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial, 11 of 20 adults showed improvement in ADHD symptoms within 3 weeks of starting atomoxetine.24

- In 297 children and adolescents, atomoxetine at dosages averaging approximately 1.2 mg/kg/d was more effective than a placebo in reducing ADHD symptoms and improving social and family functioning. Treatment was well tolerated and without significant side effects.25

- In a randomized open-label trial, 228 children received atomoxetine or methylphenidate. Both treatments significantly reduced inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.26

Related resources

- Arnsten AF. Genetics of childhood disorders (XVIII). ADHD, Part 2: Norepinephrine has a critical modulatory influence on prefrontal cortical function. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1201-3.

- Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: An aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885-90.

- Research Report: Prescription Drugs—abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Higgins reports that he is on the speakers’ bureaus for Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly and Co.

1. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, et al. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:565-76.

2. Sullivan MA, Rudnik-Levin F. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;931:251-70.

3. Hunt RD. Nosology, neurobiology, and clinical patterns of ADHD in adults. Psychiatric Ann 1997;27:572-81.

4. Taylor MA. Evaluation and management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am Fam Phys 1997;55:887-904.

5. Diller LH. The run on Ritalin. Attention deficit disorder and stimulant treatment in the 1990s. Hasting Center Report 1996;26:12-18.

6. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, et al. Prescribing trends in psychotrophic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998;279:526-31.

7. Mortan WA, Stockton GG. Methylphenidate abuse and psychiatric side effects. J Clin Psychiatry (Primary Care) 2000;2:159-64.

8. Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

9. Banov MD, Palmer T, Brody E. Antidepressants are as effective as stimulants in the long-term treatment of ADHD in Adults. Primary Psychiatry 2001;8:54-7.

10. Moline S, Frankenberger W. Use of stimulant medication for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A survey of middle and high school students attitudes. Psychology in the Schools 2001;38:569-84.

11. Prescription drugs: abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series. NIH publication number 01-4881, July 2001.

12. Mann A. Illicit methylphenidate trade appears widespread. Clinical Psychiatry News June 2000;28(6):5-

13. ABCNews.com. http://more/abcnews.go.com/sections/living/DailyNews/ritalin0505.html

14. Higgins ES. A comparative analysis of antidepressants and stimulants for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Fam Pract 1999;48:15-20.

15. Arnsten AF, Steere JC, Hunt RD. The contribution of alpha2-noradrenergic mechanisms to prefrontal cortical cognitive function. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:448-55.

16. DuPaul G. The ADHD Rating Scale: normative data, reliability, and validity. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School, 1990.

17. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.

18. Spencer T, Wilens T, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ablon JS, Lapey K. A double-blind, crossover comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:434-43.

19. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:282-8.

20. Kuperman S, Perry PJ, Gaffney GR, et al. Bupropion SR vs. methylphenidate vs. placebo for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:129-34.

21. Wooltorton E. Bupropion (Zyban, Wellbutrin SR): reports of death, seizures, serum sickness. Can Med J 2002;166:68.-

22. Upadhyaya HP, Brady KT, Sethuraman G, et al. Venlafaxine treatment of patients with comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:116-8.

23. Thase ME. Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3744 depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:502-8.

24. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Prince J, Hatch M. Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:693-5.

25. Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics 2001;108:E83.-

26. Kratochvil C, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R, et al. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in ADHD children: a randomized, open-label trial (presentation). Honolulu: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October, 2001.

Should you prescribe a stimulant to treat attention and hyperactivity problems in teenagers and adults with a history of substance abuse? Evidence suggests that using a stimulant to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may place such patients at risk for stimulant abuse or for relapse into abuse of other substances. But a stimulant may be the only option for patients whose ADHD symptoms do not respond to alternate medications, such as antidepressants.

Growing numbers of adults are being treated for ADHD. Because substance abuse problems are common in adults with ADHD (Box 1 ),1-3 prescribing an antidepressant instead of a stimulant in some cases may be prudent. Consider the following factors when choosing ADHD therapy for patients with a history of substance abuse.

Prevalence of stimulant use and abuse

In the United States, more than 95% of medications prescribed for children and adults with ADHD are stimulants—usually methylphenidate.4 Stimulant use has increased as more children and adults are diagnosed with ADHD. Methylphenidate prescriptions increased five-fold from 1990 to 1995.5 Visits to psychiatrists and physicians that included stimulant prescriptions grew from 570,000 to 2.86 million from 1985 to 1994, with most of that increase occurring during visits to primary care and other physicians.6

When used as prescribed, methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating most children and adults with ADHD. Methylphenidate’s pharmacologic properties, however, are similar to those of amphetamines and cocaine (Box 2, Figure 1),7,8 which is why methylphenidate is a schedule-II controlled substance.

Published data. Fifteen reports of methylphenidate abuse were published in the medical literature between 1960 and 1999,7 but little is known about the prevalence of stimulant abuse among patients with ADHD. Banov and colleagues recently published what may be the only data available, when they reported that 3 of 37 (8%) patients abused the stimulants they were prescribed for ADHD.9 The three patients who abused stimulants had histories of drug and alcohol abuse at study entry. In all three cases, stimulant abuse did not develop immediately but became apparent within 6 months after the study began.

In a study of 651 students ages 11 to 18 in Wisconsin and Minnesota, more than one-third of those taking stimulants reported being asked to sell or trade their medications. More than one-half of those not taking ADHD medications said they knew someone who sold or gave away his or her medication.10

Stimulant theft, recreational use. Methylphenidate has been identified as the third most abused prescribed substance in the United States.11 It was the 10th most frequently stolen controlled drug from pharmacies between 1990 and 1995, and 700,000 dosage units were reported stolen in 1996 and 1997.12

As many as 50% of adults with ADHD have substance abuse problems (including alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana), and as many as 30% have antisocial personality disorder (with increased potential for drug-seeking behaviors).1 Compared with the general population, persons with ADHD have an earlier onset of substance abuse that is less responsive to treatment and more likely to progress from alcohol to other drugs.2

The elevated risk of substance abuse in ADHD may be related to a subtle lack of response to normal positive and negative reinforcements. Hunt has outlined four neurobehavioral deficits that define ADHD.3 Besides inattention, hyperarousal, and impulsiveness, he proposes that persons with ADHD have a reward system deficit. They may gravitate toward substance abuse because drugs, alcohol, and nicotine provide stronger rewards than life’s more subtle social interactions.

The popular media have reported recreational use of methylphenidate—with street names such as “R-Ball” and “Vitamin R”—among teens and college students.13 Illegal stimulants are perceived to be easily accessible on college campuses, but no data have been reported.

The use of stimulant medication for ADHD patients with substance abuse problems remains controversial. For such patients, this author reserves stimulant medication for those:

- whose ADHD symptoms have not responded adequately to alternate treatments

- who have been reliable with prescription medications

- and whose functional level is seriously impaired by their ADHD.

Antidepressants vs. stimulants

Although few well-designed controlled studies have been published, four antidepressants appear to be reasonably equivalent in effectiveness for adults with ADHD and do not carry potential for stimulant abuse.14

Desipraime, bupropion, venlafaxine, and the experimental drug atomoxetine (Table 1) all increase norepinephrine at the synapse by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake. Though dopamine has traditionally been considered the neurotransmitter of choice for ADHD treatment, norepinephrine may be equally potent.

Impulse control center. Several lines of research have recently established a connection between the prefrontal cortex, norepinephrine, and ADHD.15 This evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex plays a major role in inhibiting impulses and responses to distractions:

Figure 1

PET scans of the brain using carbon 11 (11C)-labeled cocaine and methylphenidate HCl show similar distributions in the striatium when the drugs are administered intravenously.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

Stimulants are classified as schedule-II drugs because they produce powerful reinforcing effects by increasing synaptic dopamine.7 Positron-emission tomography (PET) scans using carbon labeling have shown similar distributions of methylphenidate and cocaine in the brain (Figure 1).8 When administered intravenously, both drugs occupy the same receptors in the striatum and produce a “high” that parallels rapid neuronal uptake. Methylphenidate and cocaine similarly increase stimulation of the postsynaptic neuron by blocking the dopamine reuptake pump (dopamine transporter).

How a substance gets to the brain’s euphoric receptors greatly affects its addictive properties. Delivery systems with rapid onset—smoking, “snorting,” or IV injection—have much greater ability to produce a “high” than do oral or transdermal routes. The greater the “high,” the greater the potential for abuse.

Because methylphenidate is prescribed for oral use, the potential for abuse is minimal. However, we need to be extremely cautious when giving methylphenidate or similar stimulant medications to patients who have shown they are unable to control their abuse of other substances.

Stimulants can also re-ignite a dormant substance abuse problem. Though little has been written about this in the medical literature, Elizabeth Wurtzel, author of the controversial Prozac Nation, chronicles the resumption of her cocaine abuse in More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction. She contends that after her doctor added methylphenidate to augment treatment of partially remitting depression, she began abusing it and eventually was using 40 tablets per day before slipping back into cocaine dependence.

- Patients with prefrontal cortex deficits can have problems with inattention and poor impulse control.

- Patients with ADHD have frontal lobe impairments, as neuropsychological testing and imaging studies have shown.

- Norepinephrine neurons, with cell bodies in the locus coeruleus, have projections that terminate in the prefrontal cortex.

- Agents with norepinephrine activity, but without mood-altering properties (e.g., clonidine), have been shown to improve ADHD symptoms.

Table 1

ADHD IN ADULTS: ANTIDEPRESSANT DOSAGES AND SIDE EFFECTS

| Medication | Class | Effective dosage | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desipramine | Tricyclic | 100 to 200 mg/d | Sedation, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, prolonged cardiac conduction time; may be lethal in overdose |

| Bupropion SR | Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 150 mg bid to 200 mg bid | Headaches, insomnia, agitation, increased risk of seizures |

| Venlafaxine XR | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 75 to 225 mg/d | Nausea, sexual side effects, agitation, increased blood pressure at higher dosages |

| Atomoxetine* | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | To be determined | To be determined |

| * Investigational agent; not FDA-approved | |||

Additional evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex has projections back to the locus coeruleus, which may explain the relationship between the two areas. It may be that the brain’s higher-functioning areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, provide intelligent screening of impulses from the brain’s older areas, such as the locus coeruleus. Therefore, increased prefrontal cortex activity may modulate some impulses that ADHD patients cannot control otherwise.

No ‘high’ with antidepressants. Patients with ADHD who have experienced the powerful effects of street drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or even alcohol may report that antidepressants do not provide the effect they desire. It is difficult to know if these patients are reporting a lack of benefit or simply the absence of a euphoric “high” they are used to experiencing with substances of abuse. The newer antidepressants do not activate the brain’s euphoric receptors to an appreciable degree.

Patients who take stimulants as prescribed also do not report a “high” but can detect the medication’s presence and absence. Most do not crave this feeling, but substance abusers tend to like it. A patient recently told me he didn’t think stimulants improved his ADHD, but said, “I just liked the way they made me feel.”

Desipramine

The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine is a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is effective in treating ADHD in children and adults. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with ADHD, subjects receiving desipramine showed robust improvement in symptom scores on the ADHD Rating Scale,16 compared with those receiving the placebo (Figure 2).17

During the 6-week trial, 41 adults with ADHD received desipramine, 200 mg/d, or a placebo. Those receiving desipramine showed significant improvement in 12 of 14 ADHD symptoms and less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness, whereas those receiving the placebo showed no improvement. According to the study criteria, 68% of those who received desipramine and none who received the placebo were considered positive responders.

Though no head-to-head studies have compared desipramine with methylphenidate, the same researchers conducted a similar placebo-controlled study with methylphenidate. The 6-week symptom score on the ADHD Rating Scale was 12.5 for methylphenidate, compared with a score of 12 for desipramine.18

Recommendation. Desipramine may be the most effective of the antidepressant treatments for patients with ADHD. Because of its side effects, however, it is not this author’s first choice and is usually reserved for patients whose symptoms fail to respond to other antidepressants. Desipramine can cause sedation, dry mouth, and constipation, which are related to blockade of adrenergic, histamine, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. It also can be lethal in overdose.

Some substance abusers lose confidence in a medication that they cannot feel working. The side effects of desipramine, which can be intolerable for some patients, can reassure others with a history of substance abuse that they are being medicated.

Bupropion

Bupropion is a unique antidepressant that inhibits the presynaptic reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. Open-label studies demonstrate good responses to bupropion by adults with ADHD. One placebo-controlled, double-blind study found improved ADHD symptoms in 76% of patients receiving bupropion SR, compared with 37% of those receiving a placebo; the difference was statistically significant.19

Figure 2 IMPROVED ADHD SYMPTOMS WITH DESIPRAMINE

Adults with ADHD who received desipramine, 200 mg/d, in a double-blind trial showed significantly less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness after 6 weeks of therapy than a control group that received a placebo.

Source: Adapted with permission from Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.Another study of adults with ADHD compared bupropion SR to methylphenidate and a placebo.20 Using a primary outcome of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, response rates were 64% for bupropion SR, 50% for methylphenidate, and 27% for the placebo. The difference in response rates between the two agents was not statistically significant (p = 0.14).

Recommendation. The risk of seizures with bupropion is about 1 in 1,000. Therefore, bupropion should not be given to patients with a seizure disorder or to those with conditions that alter the seizure threshold (e.g., eating disorders, recent head trauma, or benzodiazepine withdrawal).21

This author uses bupropion as first-line treatment for appropriate patients with ADHD and a substance abuse history. Bupropion’s mild benefit with smoking cessation may provide some crossover effect for other substances of abuse. The low incidence of sexual side effects is another benefit. Drawbacks include twice-daily dosing and lack of a robust effect on attention and concentration.

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine is a potent inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, a moderate inhibitor of norepinephrine, and a mild inhibitor of dopamine. Venlafaxine has displayed response rates similar to those of desipramine and bupropion in open-label studies in adults with ADHD,14 but no placebo-controlled studies exist.

As noted above, these antidepressants are believed to improve ADHD symptoms by making norepinephrine more available at the synapse. Hypothetically, then, one would need to administer venlafaxine at dosages that adequately inhibit the norepinephrine reuptake receptor. Venlafaxine XR, 150 mg/d, provides significant norepinephrine activity, according to several lines of evidence.

Recently, Upadhyaya et al reported the use of venlafaxine in one of the few treatment studies of patients with ADHD and comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse. In an open-label trial, 10 subjects received venlafaxine, up to 300 mg/d, along with psychotherapy and attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The nine who completed 4 weeks of treatment showed significantly improved ADHD symptoms and decreased alcohol craving.22

Recommendation. Venlafaxine is this author’s second choice for patients with ADHD and substance abuse problems. Sexual side effects that some patients experience with venlafaxine can limit its use. Some clinicians are concerned about increases in blood pressure associated with venlafaxine, although significant changes do not seem to occur at dosages below 300 mg/d.23

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is an investigational antidepressant in phase-III trials as a treatment for ADHD. Evidence shows atomoxetine to be a potent inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter, with minimal affinity for other neurotransmitter receptors. Initial studies suggest that atomoxetine is effective for adults and children with ADHD:

- In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial, 11 of 20 adults showed improvement in ADHD symptoms within 3 weeks of starting atomoxetine.24

- In 297 children and adolescents, atomoxetine at dosages averaging approximately 1.2 mg/kg/d was more effective than a placebo in reducing ADHD symptoms and improving social and family functioning. Treatment was well tolerated and without significant side effects.25

- In a randomized open-label trial, 228 children received atomoxetine or methylphenidate. Both treatments significantly reduced inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.26

Related resources

- Arnsten AF. Genetics of childhood disorders (XVIII). ADHD, Part 2: Norepinephrine has a critical modulatory influence on prefrontal cortical function. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1201-3.

- Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: An aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885-90.

- Research Report: Prescription Drugs—abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Higgins reports that he is on the speakers’ bureaus for Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly and Co.

Should you prescribe a stimulant to treat attention and hyperactivity problems in teenagers and adults with a history of substance abuse? Evidence suggests that using a stimulant to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may place such patients at risk for stimulant abuse or for relapse into abuse of other substances. But a stimulant may be the only option for patients whose ADHD symptoms do not respond to alternate medications, such as antidepressants.

Growing numbers of adults are being treated for ADHD. Because substance abuse problems are common in adults with ADHD (Box 1 ),1-3 prescribing an antidepressant instead of a stimulant in some cases may be prudent. Consider the following factors when choosing ADHD therapy for patients with a history of substance abuse.

Prevalence of stimulant use and abuse

In the United States, more than 95% of medications prescribed for children and adults with ADHD are stimulants—usually methylphenidate.4 Stimulant use has increased as more children and adults are diagnosed with ADHD. Methylphenidate prescriptions increased five-fold from 1990 to 1995.5 Visits to psychiatrists and physicians that included stimulant prescriptions grew from 570,000 to 2.86 million from 1985 to 1994, with most of that increase occurring during visits to primary care and other physicians.6

When used as prescribed, methylphenidate is safe and effective for treating most children and adults with ADHD. Methylphenidate’s pharmacologic properties, however, are similar to those of amphetamines and cocaine (Box 2, Figure 1),7,8 which is why methylphenidate is a schedule-II controlled substance.

Published data. Fifteen reports of methylphenidate abuse were published in the medical literature between 1960 and 1999,7 but little is known about the prevalence of stimulant abuse among patients with ADHD. Banov and colleagues recently published what may be the only data available, when they reported that 3 of 37 (8%) patients abused the stimulants they were prescribed for ADHD.9 The three patients who abused stimulants had histories of drug and alcohol abuse at study entry. In all three cases, stimulant abuse did not develop immediately but became apparent within 6 months after the study began.

In a study of 651 students ages 11 to 18 in Wisconsin and Minnesota, more than one-third of those taking stimulants reported being asked to sell or trade their medications. More than one-half of those not taking ADHD medications said they knew someone who sold or gave away his or her medication.10

Stimulant theft, recreational use. Methylphenidate has been identified as the third most abused prescribed substance in the United States.11 It was the 10th most frequently stolen controlled drug from pharmacies between 1990 and 1995, and 700,000 dosage units were reported stolen in 1996 and 1997.12

As many as 50% of adults with ADHD have substance abuse problems (including alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana), and as many as 30% have antisocial personality disorder (with increased potential for drug-seeking behaviors).1 Compared with the general population, persons with ADHD have an earlier onset of substance abuse that is less responsive to treatment and more likely to progress from alcohol to other drugs.2

The elevated risk of substance abuse in ADHD may be related to a subtle lack of response to normal positive and negative reinforcements. Hunt has outlined four neurobehavioral deficits that define ADHD.3 Besides inattention, hyperarousal, and impulsiveness, he proposes that persons with ADHD have a reward system deficit. They may gravitate toward substance abuse because drugs, alcohol, and nicotine provide stronger rewards than life’s more subtle social interactions.

The popular media have reported recreational use of methylphenidate—with street names such as “R-Ball” and “Vitamin R”—among teens and college students.13 Illegal stimulants are perceived to be easily accessible on college campuses, but no data have been reported.

The use of stimulant medication for ADHD patients with substance abuse problems remains controversial. For such patients, this author reserves stimulant medication for those:

- whose ADHD symptoms have not responded adequately to alternate treatments

- who have been reliable with prescription medications

- and whose functional level is seriously impaired by their ADHD.

Antidepressants vs. stimulants

Although few well-designed controlled studies have been published, four antidepressants appear to be reasonably equivalent in effectiveness for adults with ADHD and do not carry potential for stimulant abuse.14

Desipraime, bupropion, venlafaxine, and the experimental drug atomoxetine (Table 1) all increase norepinephrine at the synapse by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake. Though dopamine has traditionally been considered the neurotransmitter of choice for ADHD treatment, norepinephrine may be equally potent.

Impulse control center. Several lines of research have recently established a connection between the prefrontal cortex, norepinephrine, and ADHD.15 This evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex plays a major role in inhibiting impulses and responses to distractions:

Figure 1

PET scans of the brain using carbon 11 (11C)-labeled cocaine and methylphenidate HCl show similar distributions in the striatium when the drugs are administered intravenously.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

Stimulants are classified as schedule-II drugs because they produce powerful reinforcing effects by increasing synaptic dopamine.7 Positron-emission tomography (PET) scans using carbon labeling have shown similar distributions of methylphenidate and cocaine in the brain (Figure 1).8 When administered intravenously, both drugs occupy the same receptors in the striatum and produce a “high” that parallels rapid neuronal uptake. Methylphenidate and cocaine similarly increase stimulation of the postsynaptic neuron by blocking the dopamine reuptake pump (dopamine transporter).

How a substance gets to the brain’s euphoric receptors greatly affects its addictive properties. Delivery systems with rapid onset—smoking, “snorting,” or IV injection—have much greater ability to produce a “high” than do oral or transdermal routes. The greater the “high,” the greater the potential for abuse.

Because methylphenidate is prescribed for oral use, the potential for abuse is minimal. However, we need to be extremely cautious when giving methylphenidate or similar stimulant medications to patients who have shown they are unable to control their abuse of other substances.

Stimulants can also re-ignite a dormant substance abuse problem. Though little has been written about this in the medical literature, Elizabeth Wurtzel, author of the controversial Prozac Nation, chronicles the resumption of her cocaine abuse in More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction. She contends that after her doctor added methylphenidate to augment treatment of partially remitting depression, she began abusing it and eventually was using 40 tablets per day before slipping back into cocaine dependence.

- Patients with prefrontal cortex deficits can have problems with inattention and poor impulse control.

- Patients with ADHD have frontal lobe impairments, as neuropsychological testing and imaging studies have shown.

- Norepinephrine neurons, with cell bodies in the locus coeruleus, have projections that terminate in the prefrontal cortex.

- Agents with norepinephrine activity, but without mood-altering properties (e.g., clonidine), have been shown to improve ADHD symptoms.

Table 1

ADHD IN ADULTS: ANTIDEPRESSANT DOSAGES AND SIDE EFFECTS

| Medication | Class | Effective dosage | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desipramine | Tricyclic | 100 to 200 mg/d | Sedation, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, prolonged cardiac conduction time; may be lethal in overdose |

| Bupropion SR | Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 150 mg bid to 200 mg bid | Headaches, insomnia, agitation, increased risk of seizures |

| Venlafaxine XR | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 75 to 225 mg/d | Nausea, sexual side effects, agitation, increased blood pressure at higher dosages |

| Atomoxetine* | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | To be determined | To be determined |

| * Investigational agent; not FDA-approved | |||

Additional evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex has projections back to the locus coeruleus, which may explain the relationship between the two areas. It may be that the brain’s higher-functioning areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, provide intelligent screening of impulses from the brain’s older areas, such as the locus coeruleus. Therefore, increased prefrontal cortex activity may modulate some impulses that ADHD patients cannot control otherwise.

No ‘high’ with antidepressants. Patients with ADHD who have experienced the powerful effects of street drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or even alcohol may report that antidepressants do not provide the effect they desire. It is difficult to know if these patients are reporting a lack of benefit or simply the absence of a euphoric “high” they are used to experiencing with substances of abuse. The newer antidepressants do not activate the brain’s euphoric receptors to an appreciable degree.

Patients who take stimulants as prescribed also do not report a “high” but can detect the medication’s presence and absence. Most do not crave this feeling, but substance abusers tend to like it. A patient recently told me he didn’t think stimulants improved his ADHD, but said, “I just liked the way they made me feel.”

Desipramine

The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine is a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is effective in treating ADHD in children and adults. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with ADHD, subjects receiving desipramine showed robust improvement in symptom scores on the ADHD Rating Scale,16 compared with those receiving the placebo (Figure 2).17

During the 6-week trial, 41 adults with ADHD received desipramine, 200 mg/d, or a placebo. Those receiving desipramine showed significant improvement in 12 of 14 ADHD symptoms and less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness, whereas those receiving the placebo showed no improvement. According to the study criteria, 68% of those who received desipramine and none who received the placebo were considered positive responders.

Though no head-to-head studies have compared desipramine with methylphenidate, the same researchers conducted a similar placebo-controlled study with methylphenidate. The 6-week symptom score on the ADHD Rating Scale was 12.5 for methylphenidate, compared with a score of 12 for desipramine.18

Recommendation. Desipramine may be the most effective of the antidepressant treatments for patients with ADHD. Because of its side effects, however, it is not this author’s first choice and is usually reserved for patients whose symptoms fail to respond to other antidepressants. Desipramine can cause sedation, dry mouth, and constipation, which are related to blockade of adrenergic, histamine, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. It also can be lethal in overdose.

Some substance abusers lose confidence in a medication that they cannot feel working. The side effects of desipramine, which can be intolerable for some patients, can reassure others with a history of substance abuse that they are being medicated.

Bupropion

Bupropion is a unique antidepressant that inhibits the presynaptic reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. Open-label studies demonstrate good responses to bupropion by adults with ADHD. One placebo-controlled, double-blind study found improved ADHD symptoms in 76% of patients receiving bupropion SR, compared with 37% of those receiving a placebo; the difference was statistically significant.19

Figure 2 IMPROVED ADHD SYMPTOMS WITH DESIPRAMINE

Adults with ADHD who received desipramine, 200 mg/d, in a double-blind trial showed significantly less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness after 6 weeks of therapy than a control group that received a placebo.

Source: Adapted with permission from Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.Another study of adults with ADHD compared bupropion SR to methylphenidate and a placebo.20 Using a primary outcome of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, response rates were 64% for bupropion SR, 50% for methylphenidate, and 27% for the placebo. The difference in response rates between the two agents was not statistically significant (p = 0.14).

Recommendation. The risk of seizures with bupropion is about 1 in 1,000. Therefore, bupropion should not be given to patients with a seizure disorder or to those with conditions that alter the seizure threshold (e.g., eating disorders, recent head trauma, or benzodiazepine withdrawal).21

This author uses bupropion as first-line treatment for appropriate patients with ADHD and a substance abuse history. Bupropion’s mild benefit with smoking cessation may provide some crossover effect for other substances of abuse. The low incidence of sexual side effects is another benefit. Drawbacks include twice-daily dosing and lack of a robust effect on attention and concentration.

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine is a potent inhibitor of serotonin reuptake, a moderate inhibitor of norepinephrine, and a mild inhibitor of dopamine. Venlafaxine has displayed response rates similar to those of desipramine and bupropion in open-label studies in adults with ADHD,14 but no placebo-controlled studies exist.

As noted above, these antidepressants are believed to improve ADHD symptoms by making norepinephrine more available at the synapse. Hypothetically, then, one would need to administer venlafaxine at dosages that adequately inhibit the norepinephrine reuptake receptor. Venlafaxine XR, 150 mg/d, provides significant norepinephrine activity, according to several lines of evidence.

Recently, Upadhyaya et al reported the use of venlafaxine in one of the few treatment studies of patients with ADHD and comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse. In an open-label trial, 10 subjects received venlafaxine, up to 300 mg/d, along with psychotherapy and attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The nine who completed 4 weeks of treatment showed significantly improved ADHD symptoms and decreased alcohol craving.22

Recommendation. Venlafaxine is this author’s second choice for patients with ADHD and substance abuse problems. Sexual side effects that some patients experience with venlafaxine can limit its use. Some clinicians are concerned about increases in blood pressure associated with venlafaxine, although significant changes do not seem to occur at dosages below 300 mg/d.23

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is an investigational antidepressant in phase-III trials as a treatment for ADHD. Evidence shows atomoxetine to be a potent inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter, with minimal affinity for other neurotransmitter receptors. Initial studies suggest that atomoxetine is effective for adults and children with ADHD:

- In a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial, 11 of 20 adults showed improvement in ADHD symptoms within 3 weeks of starting atomoxetine.24

- In 297 children and adolescents, atomoxetine at dosages averaging approximately 1.2 mg/kg/d was more effective than a placebo in reducing ADHD symptoms and improving social and family functioning. Treatment was well tolerated and without significant side effects.25

- In a randomized open-label trial, 228 children received atomoxetine or methylphenidate. Both treatments significantly reduced inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.26

Related resources

- Arnsten AF. Genetics of childhood disorders (XVIII). ADHD, Part 2: Norepinephrine has a critical modulatory influence on prefrontal cortical function. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1201-3.

- Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: An aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885-90.

- Research Report: Prescription Drugs—abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Drug brand names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Concerta

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

Dr. Higgins reports that he is on the speakers’ bureaus for Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly and Co.

1. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, et al. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:565-76.

2. Sullivan MA, Rudnik-Levin F. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;931:251-70.

3. Hunt RD. Nosology, neurobiology, and clinical patterns of ADHD in adults. Psychiatric Ann 1997;27:572-81.

4. Taylor MA. Evaluation and management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am Fam Phys 1997;55:887-904.

5. Diller LH. The run on Ritalin. Attention deficit disorder and stimulant treatment in the 1990s. Hasting Center Report 1996;26:12-18.

6. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, et al. Prescribing trends in psychotrophic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998;279:526-31.

7. Mortan WA, Stockton GG. Methylphenidate abuse and psychiatric side effects. J Clin Psychiatry (Primary Care) 2000;2:159-64.

8. Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

9. Banov MD, Palmer T, Brody E. Antidepressants are as effective as stimulants in the long-term treatment of ADHD in Adults. Primary Psychiatry 2001;8:54-7.

10. Moline S, Frankenberger W. Use of stimulant medication for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A survey of middle and high school students attitudes. Psychology in the Schools 2001;38:569-84.

11. Prescription drugs: abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series. NIH publication number 01-4881, July 2001.

12. Mann A. Illicit methylphenidate trade appears widespread. Clinical Psychiatry News June 2000;28(6):5-

13. ABCNews.com. http://more/abcnews.go.com/sections/living/DailyNews/ritalin0505.html

14. Higgins ES. A comparative analysis of antidepressants and stimulants for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Fam Pract 1999;48:15-20.

15. Arnsten AF, Steere JC, Hunt RD. The contribution of alpha2-noradrenergic mechanisms to prefrontal cortical cognitive function. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:448-55.

16. DuPaul G. The ADHD Rating Scale: normative data, reliability, and validity. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School, 1990.

17. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.

18. Spencer T, Wilens T, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ablon JS, Lapey K. A double-blind, crossover comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:434-43.

19. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:282-8.

20. Kuperman S, Perry PJ, Gaffney GR, et al. Bupropion SR vs. methylphenidate vs. placebo for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:129-34.

21. Wooltorton E. Bupropion (Zyban, Wellbutrin SR): reports of death, seizures, serum sickness. Can Med J 2002;166:68.-

22. Upadhyaya HP, Brady KT, Sethuraman G, et al. Venlafaxine treatment of patients with comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:116-8.

23. Thase ME. Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3744 depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:502-8.

24. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Prince J, Hatch M. Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:693-5.

25. Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics 2001;108:E83.-

26. Kratochvil C, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R, et al. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in ADHD children: a randomized, open-label trial (presentation). Honolulu: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October, 2001.

1. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, et al. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:565-76.

2. Sullivan MA, Rudnik-Levin F. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;931:251-70.

3. Hunt RD. Nosology, neurobiology, and clinical patterns of ADHD in adults. Psychiatric Ann 1997;27:572-81.

4. Taylor MA. Evaluation and management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am Fam Phys 1997;55:887-904.

5. Diller LH. The run on Ritalin. Attention deficit disorder and stimulant treatment in the 1990s. Hasting Center Report 1996;26:12-18.

6. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, et al. Prescribing trends in psychotrophic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998;279:526-31.

7. Mortan WA, Stockton GG. Methylphenidate abuse and psychiatric side effects. J Clin Psychiatry (Primary Care) 2000;2:159-64.

8. Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

9. Banov MD, Palmer T, Brody E. Antidepressants are as effective as stimulants in the long-term treatment of ADHD in Adults. Primary Psychiatry 2001;8:54-7.

10. Moline S, Frankenberger W. Use of stimulant medication for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A survey of middle and high school students attitudes. Psychology in the Schools 2001;38:569-84.

11. Prescription drugs: abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series. NIH publication number 01-4881, July 2001.

12. Mann A. Illicit methylphenidate trade appears widespread. Clinical Psychiatry News June 2000;28(6):5-

13. ABCNews.com. http://more/abcnews.go.com/sections/living/DailyNews/ritalin0505.html

14. Higgins ES. A comparative analysis of antidepressants and stimulants for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Fam Pract 1999;48:15-20.

15. Arnsten AF, Steere JC, Hunt RD. The contribution of alpha2-noradrenergic mechanisms to prefrontal cortical cognitive function. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:448-55.

16. DuPaul G. The ADHD Rating Scale: normative data, reliability, and validity. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School, 1990.

17. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Prince J, et al. Six-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of desipramine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1147-53.

18. Spencer T, Wilens T, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Ablon JS, Lapey K. A double-blind, crossover comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:434-43.

19. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, et al. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:282-8.

20. Kuperman S, Perry PJ, Gaffney GR, et al. Bupropion SR vs. methylphenidate vs. placebo for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:129-34.

21. Wooltorton E. Bupropion (Zyban, Wellbutrin SR): reports of death, seizures, serum sickness. Can Med J 2002;166:68.-

22. Upadhyaya HP, Brady KT, Sethuraman G, et al. Venlafaxine treatment of patients with comorbid alcohol/cocaine abuse and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:116-8.

23. Thase ME. Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3744 depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:502-8.

24. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Prince J, Hatch M. Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:693-5.

25. Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics 2001;108:E83.-

26. Kratochvil C, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R, et al. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in ADHD children: a randomized, open-label trial (presentation). Honolulu: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, October, 2001.