User login

This article, by Dr. John Inadomi and colleagues is part of the AGA’s process for developing guidelines. The importance of guidelines has increased considerably over the last 25 years. In the first wave of managed care, we were practicing with few if any clinical guidelines. Now, as we move forward toward a value-based reimbursement system, the need for evidence-based practice is paramount. Dr Inadomi and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee have fine-tuned this process over the last 3 years and now describe their results. While many guidelines are labeled as "GRADE," some are simply opinion documents designed with GRADE wording. A fully implemented GRADE process involves rigorous analysis of published data, input from trained GRADE methodologists, and opportunities for both public and expert comment from all involved stakeholders.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

The economic foundation upon which U.S. health care delivery is built is shifting rapidly. Specifically, reimbursement is changing from fee for service to value-based payments. These include bundled payments for episodes of care, and payments tied to health outcomes with shared reimbursement in which payments are distributed among all stakeholders including primary care, specialty physicians, and hospital systems. Under bundled reimbursement, payments are established a priori for each episode of care, payments will be risk adjusted, and reimbursement will not increase based on the quantity of services provided. Most importantly, payment will be modified based on providers documenting their success in achieving high-quality health outcomes and patient satisfaction compared with similar facilities servicing similar patients.

We are moving rapidly to value-based reimbursement and such changes no longer require the federal government to continue transformation of the health care landscape. In 2009, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts compared costs and quality between traditional fee-for-service and a global payment system (the Alternative Quality Contract) whereby participating provider organizations assumed accountability for spending, but also received bonuses for quality.1 Geisinger Health System, an integrated delivery system comprising hospitals, outpatient facilities, and community practices including both employed and affiliated primary care and specialty physicians, now treats 20% of total physician compensation as variable and directly dependent on annual individual and group performance.2

Based on these developments, the most important issue to address is how health care quality is defined. Traditionally, metric development and validation have been the purview of administrators. It is the premise of the AGA Institute that physicians who provide services should lead efforts to define metrics by which our clinical services and health care outcomes are judged. To achieve this goal, the AGA has changed how clinical practice guidelines are constructed and has developed the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice," a coordinated program that links guidelines to clinical decision support tools, performance measures, the infrastructure by which clinicians can report their practice outcomes (the AGA Digestive Health Outcomes Registry), the Digestive Health Recognition Program, Practice Improvement Modules, and American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification. This article, the first of two that focus on the AGA’s process for guideline development, will summarize the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to determine the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations for the AGA’s guidelines.

Guideline development begins with solicitation of topics from AGA members, the AGA Council, and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee (CPQMC). The CPQMC, with guidance from the AGA Council, develops focused clinical questions for each guideline that are submitted to the AGA Governing Board for consideration. For topics approved by the Governing Board, the CPQMC identifies two content experts and one methods expert to author technical reviews, which represent the evidence basis for guideline recommendations. The guideline itself is written by a separate panel that is constructed to provide representation from all stakeholders involved in the care of patients related to the guideline topic.

The AGA Ethics Committee vets potential authors and guideline panel members to identify conflicts of interest and ensure transparency of the process.

GRADE

To impact medical practitioners, guidelines must be derived from well-constructed studies from which information can be derived to support clinical recommendations. Because published studies vary in their methods, comparison populations, and statistical strength, some commonly accepted process is needed so that clinicians can determine how reliable guideline recommendations would be. Currently, the most common methodology to judge strength of evidence (and hence strength of our recommendations) is the GRADE framework,3 an internationally recognized method implemented by more than 70 organizations. Importantly, this process is accepted by the National Quality Forum, which is the body responsible for vetting quality metrics that may be adopted by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for use in enhanced reimbursement.

The goal of clinical practice guidelines is multifold; to improve patient care and health outcomes, to reduce inappropriate variations in practice, to promote efficient use of resources, and to help define and inform public policy. Although there has been an increase in the number of guidelines over the past 5 years, uptake and adoption of guidelines has been hindered by a number of factors; notably, lack of transparency, lack of a uniform system to rate evidence that informs the guideline, lack of trust in recommendations, and ineffective management of conflicts of interest. Recognizing these deficiencies, a recent Institute of Medicine report defined standards for the development of high-quality guidelines.4

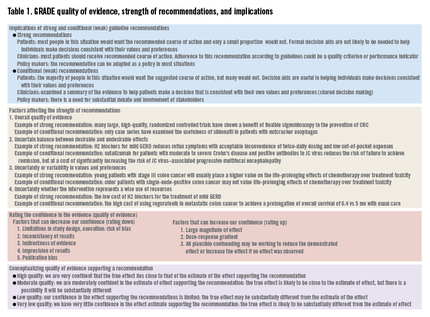

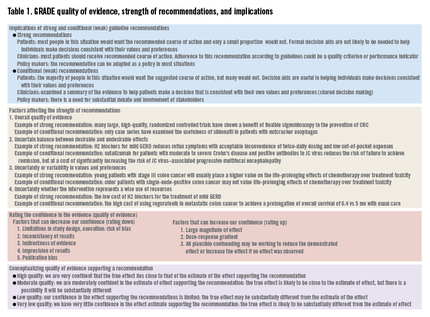

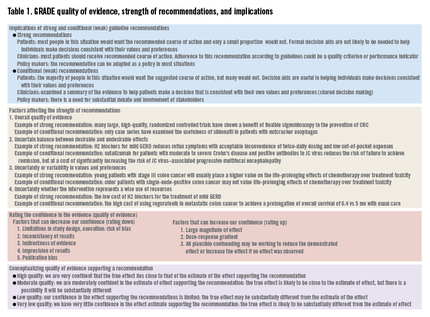

GRADE’s methodologically rigorous framework and binary classification of strong vs. conditional (weak) recommendations provides a clear and actionable direction to patients, clinicians, and policy makers. A strong recommendation means that most patients should receive the recommended course of action, whereas a conditional recommendation means that different choices will be appropriate for different patients (Table 1).

Developing a guideline using GRADE

Defining the clinical question

The first step within the GRADE framework is to formulate the clinical questions to be addressed. This not only helps to define the focus of the guideline but it also outlines the criteria for the search strategy that will be used to identify the body of evidence. The clinical question should include the following four components: patient population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO format).

Consider the following: does daily aspirin for chemoprevention reduce the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC)? This informal question would yield a relatively large number of studies that vary with respect to study design (observational studies vs. randomized controlled trials), patient population (patients with hereditary cancer syndromes vs. a personal history of adenomas), interventions (low-dose aspirin vs. regular-dose aspirin), comparators (aspirin vs. cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors), as well as outcomes (recurrent adenomas vs. advanced adenomas vs. cancer). A more appropriate clinical question may be the following: in average-risk patients with no prior history of CRC or adenomas, does regular-dose aspirin vs. no aspirin reduce the incidence of CRC? This latter PICO is defined more clearly and translates into a search strategy that may yield more relevant studies.

Not all outcomes are equally important

GRADE categorizes outcomes as critical for decision making, important but not critical (for decision making), and those that are less or not important for decision making. This explicit ranking of outcomes within a hierarchy is important because in GRADE the quality of evidence is determined for each outcome. This is in contrast to other systems of guideline development, in which quality is determined by study type and on a study-by-study basis. For example, in developing a guideline for stool testing for CRC, outcomes such as CRC-related mortality may be considered critical outcomes, incidence of advanced adenomas or minor procedure-related complications may be important, but not critical outcomes, and, finally, incidence of diminutive polyps may be considered less important outcomes.

A high-quality guideline requires a systematic review of the evidence

A systematic search for the evidence should be conducted or identified through sources such as the Cochrane Library or Medline. This systematic review (SR) will provide the data across individual studies used to generate a best estimate of the effect for each outcome. A guideline panel can conduct its own SR or use an existing SR that is deemed to be of sufficient quality.

Grading the quality of the evidence

GRADE defines quality as the extent to which our confidence in an estimate of the treatment effect is adequate to support a particular recommendation. The GRADE system specifies four grades of confidence in the evidence: high, moderate, low, and very low. Explicit criteria are available for rating down or rating up the quality of evidence. Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) start with a high confidence in the evidence, whereas an initial low confidence in the estimate is typical for evidence from observational studies (Table 1).

If an RCT has major methodologic limitations such as inadequate allocation concealment, lack of blinding, lack of accounting for high losses to follow-up evaluation, failure to perform an intention-to-treat analysis, selective reporting of outcomes, and stopping early for benefit, this may lower the quality of the evidence. In a recent meta-analysis comparing proton pump inhibitor therapy vs. histamine2-receptor antagonists in critically ill patients at risk for stress-related mucosal bleeding, significant methodologic issues, including lack of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, as well as high loss to follow-up evaluation, were recognized.5 The meta-analysis found less gastrointestinal bleeding among those who received proton pump inhibitors (1.3% vs. 6.6%; odds ratio, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.54), however, because of the many study limitations, we might consider rating down this body of evidence from high to moderate.

If an issue has inconsistent results, this refers to wide variability of treatment effects across individual studies. When variability in treatment effects is seen, it is important to try to identify the explanations for these inconsistent results; many times this variability may be explained by differences in populations, differences in the intervention, difference in outcome measures, or differences in study methodology. When no explanation for the inconsistency in results is identified, this may lower our confidence in the estimate of effect across the body of evidence.

More often than not, direct comparisons of interventions (e.g., how does fecal immunochemical testing compare with colonoscopy in reducing CRC mortality?) are unavailable, introducing uncertainty of comparative effectiveness. In addition, the existing body of evidence may differ with respect to the population, intervention, or outcome as it relates to a specific clinical question.

When studies include few patients or few events, the estimates of effect have wide confidence intervals that include benefit and no effect, or even potentially harm. In a systematic review on the use of thiopurines vs. placebo for induction of remission in adults with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, the pooled estimate from five RCTs showed a relative risk of 0.87 (95% confidence interval, 0.71-1.06) for the outcome of failure of remission, with the lower boundary of the 95% confidence interval suggesting a close to 30% benefit, but the upper boundary failing to show an effect.6 Although the pooled estimate suggests that thiopurines are beneficial, our confidence in the result is reduced because of imprecision.

Publication bias is another factor that can result in a rating down of the quality of the evidence. Often this is attributed to a lack of reporting of small studies and/or studies showing no benefit. For example, a meta-analysis of 27 publications on estimates of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus showed an inverse relationship between study size and cancer risk, suggesting publication bias and an overestimation of the risk of developing esophageal cancer (0.5% per year).7 A subsequent meta-analysis of 57 studies (11,434 patients and 58,547 patient-years of follow-up evaluation) showed a lower pooled annual risk of 0.3% per year.8

Although evidence from observational studies starts out as low-quality evidence, rating up the quality of evidence may be appropriate in specific circumstances. For example, average-risk screening colonoscopy reduces the risk of CRC mortality but the risk of colonoscopy-related splenic rupture is less clear because only case reports are available. However, as the incidence of splenic rupture in the population not screened with colonoscopy approaches zero, the resulting estimate of relative effect for splenic rupture as a result of colonoscopy is likely large, increasing our confidence in the estimate of the adverse event (Table 1).

Outcomes critical for decision making determine the overall quality of evidence

Because competing management strategies will have both beneficial outcomes as well as undesirable effects, basing the overall quality of evidence for a recommendation solely on the beneficial outcomes would be inappropriate. For example, although there is higher-quality evidence from a meta-analysis of natalizumab in reducing the risk of failure to achieve remission in Crohn’s disease,9 the overall quality of evidence should be based on the lower quality of evidence for harm (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), as long as the occurrence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy was considered critical for decision making by the guideline panel.

Making recommendations

Although the overall quality of evidence across outcomes is the defining starting point for guideline construction, additional factors, such as the balance between desirable and undesirable effects and patients’ values and preferences, need explicit considerations and may change the strength, and even the direction, of recommendations. Finally, the uncertainty of whether the recommended course of action represents a wise use of resources may need consideration depending on the perspective of the guideline panel (Table 1).

Conclusions

The GRADE process is an internationally recognized method by which clinical practice guidelines may be developed taking into account not only the quality of the evidence surrounding a specific PICO question, but also the relative benefits and harms associated with competing management strategies, potential ambiguity in patient preferences for treatments and outcomes, and the health care resources necessary to implement interventions or strategies.

The ultimate goal is the creation of clinical practice guidelines that are based on the best existing evidence, are transparent in their construction, provide clear guidance to practicing physicians, and form the basis of metrics upon which we agree to be judged. The latter is what will be required of us going forward: documentation that we are delivering high-quality health care that is proven to improve the outcomes of patients. When we achieve these goals we should be rewarded appropriately. The AGA GRADE process will ensure that gastroenterologists remain in charge of our own destiny, and that we define the optimal manner in which to care for our patients.

References

1. Song Z., Safran D.G., Landon B.E., et al. Health care spending and quality in year 1 of the alternative quality contract . N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:909-18.

2. Lee T.H., Bothe A., Steele G.D. How Geisinger structures its physicians’ compensation to support improvements in quality, efficiency, and volume. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2068-73.

3. Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6.

4. In: Graham R., Mancher M., Wolman D.M., et al. editors. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

5. Barkun A.N., Bardou M., Pham C.Q., et al. Proton pump inhibitors vs. histamine 2 receptor antagonists for stress-related mucosal bleeding prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012;107:507-20.

6. Khan K.J., Dubinsky M.C., Ford A.C., et al. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:630-42.

7. Shaheen N.J., Crosby M.A., Bozymski E.M., et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000;119:333-8.

8. Desai T.K., Krishnan K., Samala N., et al. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut 2012;61:970-6.

9. Ford A.C., Sandborn W.J., Khan K.J., et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644-59.

Dr. Sultan is Malcom Randall VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida

Dr. Ytter, Louis Stokes VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio

Dr. Inadomi, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Dr. Sultan and Dr. Falck-Ytter disclose are members of the GRADE working group and have been co-authors on GRADE-related publications. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

This article, by Dr. John Inadomi and colleagues is part of the AGA’s process for developing guidelines. The importance of guidelines has increased considerably over the last 25 years. In the first wave of managed care, we were practicing with few if any clinical guidelines. Now, as we move forward toward a value-based reimbursement system, the need for evidence-based practice is paramount. Dr Inadomi and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee have fine-tuned this process over the last 3 years and now describe their results. While many guidelines are labeled as "GRADE," some are simply opinion documents designed with GRADE wording. A fully implemented GRADE process involves rigorous analysis of published data, input from trained GRADE methodologists, and opportunities for both public and expert comment from all involved stakeholders.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

The economic foundation upon which U.S. health care delivery is built is shifting rapidly. Specifically, reimbursement is changing from fee for service to value-based payments. These include bundled payments for episodes of care, and payments tied to health outcomes with shared reimbursement in which payments are distributed among all stakeholders including primary care, specialty physicians, and hospital systems. Under bundled reimbursement, payments are established a priori for each episode of care, payments will be risk adjusted, and reimbursement will not increase based on the quantity of services provided. Most importantly, payment will be modified based on providers documenting their success in achieving high-quality health outcomes and patient satisfaction compared with similar facilities servicing similar patients.

We are moving rapidly to value-based reimbursement and such changes no longer require the federal government to continue transformation of the health care landscape. In 2009, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts compared costs and quality between traditional fee-for-service and a global payment system (the Alternative Quality Contract) whereby participating provider organizations assumed accountability for spending, but also received bonuses for quality.1 Geisinger Health System, an integrated delivery system comprising hospitals, outpatient facilities, and community practices including both employed and affiliated primary care and specialty physicians, now treats 20% of total physician compensation as variable and directly dependent on annual individual and group performance.2

Based on these developments, the most important issue to address is how health care quality is defined. Traditionally, metric development and validation have been the purview of administrators. It is the premise of the AGA Institute that physicians who provide services should lead efforts to define metrics by which our clinical services and health care outcomes are judged. To achieve this goal, the AGA has changed how clinical practice guidelines are constructed and has developed the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice," a coordinated program that links guidelines to clinical decision support tools, performance measures, the infrastructure by which clinicians can report their practice outcomes (the AGA Digestive Health Outcomes Registry), the Digestive Health Recognition Program, Practice Improvement Modules, and American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification. This article, the first of two that focus on the AGA’s process for guideline development, will summarize the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to determine the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations for the AGA’s guidelines.

Guideline development begins with solicitation of topics from AGA members, the AGA Council, and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee (CPQMC). The CPQMC, with guidance from the AGA Council, develops focused clinical questions for each guideline that are submitted to the AGA Governing Board for consideration. For topics approved by the Governing Board, the CPQMC identifies two content experts and one methods expert to author technical reviews, which represent the evidence basis for guideline recommendations. The guideline itself is written by a separate panel that is constructed to provide representation from all stakeholders involved in the care of patients related to the guideline topic.

The AGA Ethics Committee vets potential authors and guideline panel members to identify conflicts of interest and ensure transparency of the process.

GRADE

To impact medical practitioners, guidelines must be derived from well-constructed studies from which information can be derived to support clinical recommendations. Because published studies vary in their methods, comparison populations, and statistical strength, some commonly accepted process is needed so that clinicians can determine how reliable guideline recommendations would be. Currently, the most common methodology to judge strength of evidence (and hence strength of our recommendations) is the GRADE framework,3 an internationally recognized method implemented by more than 70 organizations. Importantly, this process is accepted by the National Quality Forum, which is the body responsible for vetting quality metrics that may be adopted by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for use in enhanced reimbursement.

The goal of clinical practice guidelines is multifold; to improve patient care and health outcomes, to reduce inappropriate variations in practice, to promote efficient use of resources, and to help define and inform public policy. Although there has been an increase in the number of guidelines over the past 5 years, uptake and adoption of guidelines has been hindered by a number of factors; notably, lack of transparency, lack of a uniform system to rate evidence that informs the guideline, lack of trust in recommendations, and ineffective management of conflicts of interest. Recognizing these deficiencies, a recent Institute of Medicine report defined standards for the development of high-quality guidelines.4

GRADE’s methodologically rigorous framework and binary classification of strong vs. conditional (weak) recommendations provides a clear and actionable direction to patients, clinicians, and policy makers. A strong recommendation means that most patients should receive the recommended course of action, whereas a conditional recommendation means that different choices will be appropriate for different patients (Table 1).

Developing a guideline using GRADE

Defining the clinical question

The first step within the GRADE framework is to formulate the clinical questions to be addressed. This not only helps to define the focus of the guideline but it also outlines the criteria for the search strategy that will be used to identify the body of evidence. The clinical question should include the following four components: patient population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO format).

Consider the following: does daily aspirin for chemoprevention reduce the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC)? This informal question would yield a relatively large number of studies that vary with respect to study design (observational studies vs. randomized controlled trials), patient population (patients with hereditary cancer syndromes vs. a personal history of adenomas), interventions (low-dose aspirin vs. regular-dose aspirin), comparators (aspirin vs. cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors), as well as outcomes (recurrent adenomas vs. advanced adenomas vs. cancer). A more appropriate clinical question may be the following: in average-risk patients with no prior history of CRC or adenomas, does regular-dose aspirin vs. no aspirin reduce the incidence of CRC? This latter PICO is defined more clearly and translates into a search strategy that may yield more relevant studies.

Not all outcomes are equally important

GRADE categorizes outcomes as critical for decision making, important but not critical (for decision making), and those that are less or not important for decision making. This explicit ranking of outcomes within a hierarchy is important because in GRADE the quality of evidence is determined for each outcome. This is in contrast to other systems of guideline development, in which quality is determined by study type and on a study-by-study basis. For example, in developing a guideline for stool testing for CRC, outcomes such as CRC-related mortality may be considered critical outcomes, incidence of advanced adenomas or minor procedure-related complications may be important, but not critical outcomes, and, finally, incidence of diminutive polyps may be considered less important outcomes.

A high-quality guideline requires a systematic review of the evidence

A systematic search for the evidence should be conducted or identified through sources such as the Cochrane Library or Medline. This systematic review (SR) will provide the data across individual studies used to generate a best estimate of the effect for each outcome. A guideline panel can conduct its own SR or use an existing SR that is deemed to be of sufficient quality.

Grading the quality of the evidence

GRADE defines quality as the extent to which our confidence in an estimate of the treatment effect is adequate to support a particular recommendation. The GRADE system specifies four grades of confidence in the evidence: high, moderate, low, and very low. Explicit criteria are available for rating down or rating up the quality of evidence. Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) start with a high confidence in the evidence, whereas an initial low confidence in the estimate is typical for evidence from observational studies (Table 1).

If an RCT has major methodologic limitations such as inadequate allocation concealment, lack of blinding, lack of accounting for high losses to follow-up evaluation, failure to perform an intention-to-treat analysis, selective reporting of outcomes, and stopping early for benefit, this may lower the quality of the evidence. In a recent meta-analysis comparing proton pump inhibitor therapy vs. histamine2-receptor antagonists in critically ill patients at risk for stress-related mucosal bleeding, significant methodologic issues, including lack of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, as well as high loss to follow-up evaluation, were recognized.5 The meta-analysis found less gastrointestinal bleeding among those who received proton pump inhibitors (1.3% vs. 6.6%; odds ratio, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.54), however, because of the many study limitations, we might consider rating down this body of evidence from high to moderate.

If an issue has inconsistent results, this refers to wide variability of treatment effects across individual studies. When variability in treatment effects is seen, it is important to try to identify the explanations for these inconsistent results; many times this variability may be explained by differences in populations, differences in the intervention, difference in outcome measures, or differences in study methodology. When no explanation for the inconsistency in results is identified, this may lower our confidence in the estimate of effect across the body of evidence.

More often than not, direct comparisons of interventions (e.g., how does fecal immunochemical testing compare with colonoscopy in reducing CRC mortality?) are unavailable, introducing uncertainty of comparative effectiveness. In addition, the existing body of evidence may differ with respect to the population, intervention, or outcome as it relates to a specific clinical question.

When studies include few patients or few events, the estimates of effect have wide confidence intervals that include benefit and no effect, or even potentially harm. In a systematic review on the use of thiopurines vs. placebo for induction of remission in adults with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, the pooled estimate from five RCTs showed a relative risk of 0.87 (95% confidence interval, 0.71-1.06) for the outcome of failure of remission, with the lower boundary of the 95% confidence interval suggesting a close to 30% benefit, but the upper boundary failing to show an effect.6 Although the pooled estimate suggests that thiopurines are beneficial, our confidence in the result is reduced because of imprecision.

Publication bias is another factor that can result in a rating down of the quality of the evidence. Often this is attributed to a lack of reporting of small studies and/or studies showing no benefit. For example, a meta-analysis of 27 publications on estimates of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus showed an inverse relationship between study size and cancer risk, suggesting publication bias and an overestimation of the risk of developing esophageal cancer (0.5% per year).7 A subsequent meta-analysis of 57 studies (11,434 patients and 58,547 patient-years of follow-up evaluation) showed a lower pooled annual risk of 0.3% per year.8

Although evidence from observational studies starts out as low-quality evidence, rating up the quality of evidence may be appropriate in specific circumstances. For example, average-risk screening colonoscopy reduces the risk of CRC mortality but the risk of colonoscopy-related splenic rupture is less clear because only case reports are available. However, as the incidence of splenic rupture in the population not screened with colonoscopy approaches zero, the resulting estimate of relative effect for splenic rupture as a result of colonoscopy is likely large, increasing our confidence in the estimate of the adverse event (Table 1).

Outcomes critical for decision making determine the overall quality of evidence

Because competing management strategies will have both beneficial outcomes as well as undesirable effects, basing the overall quality of evidence for a recommendation solely on the beneficial outcomes would be inappropriate. For example, although there is higher-quality evidence from a meta-analysis of natalizumab in reducing the risk of failure to achieve remission in Crohn’s disease,9 the overall quality of evidence should be based on the lower quality of evidence for harm (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), as long as the occurrence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy was considered critical for decision making by the guideline panel.

Making recommendations

Although the overall quality of evidence across outcomes is the defining starting point for guideline construction, additional factors, such as the balance between desirable and undesirable effects and patients’ values and preferences, need explicit considerations and may change the strength, and even the direction, of recommendations. Finally, the uncertainty of whether the recommended course of action represents a wise use of resources may need consideration depending on the perspective of the guideline panel (Table 1).

Conclusions

The GRADE process is an internationally recognized method by which clinical practice guidelines may be developed taking into account not only the quality of the evidence surrounding a specific PICO question, but also the relative benefits and harms associated with competing management strategies, potential ambiguity in patient preferences for treatments and outcomes, and the health care resources necessary to implement interventions or strategies.

The ultimate goal is the creation of clinical practice guidelines that are based on the best existing evidence, are transparent in their construction, provide clear guidance to practicing physicians, and form the basis of metrics upon which we agree to be judged. The latter is what will be required of us going forward: documentation that we are delivering high-quality health care that is proven to improve the outcomes of patients. When we achieve these goals we should be rewarded appropriately. The AGA GRADE process will ensure that gastroenterologists remain in charge of our own destiny, and that we define the optimal manner in which to care for our patients.

References

1. Song Z., Safran D.G., Landon B.E., et al. Health care spending and quality in year 1 of the alternative quality contract . N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:909-18.

2. Lee T.H., Bothe A., Steele G.D. How Geisinger structures its physicians’ compensation to support improvements in quality, efficiency, and volume. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2068-73.

3. Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6.

4. In: Graham R., Mancher M., Wolman D.M., et al. editors. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

5. Barkun A.N., Bardou M., Pham C.Q., et al. Proton pump inhibitors vs. histamine 2 receptor antagonists for stress-related mucosal bleeding prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012;107:507-20.

6. Khan K.J., Dubinsky M.C., Ford A.C., et al. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:630-42.

7. Shaheen N.J., Crosby M.A., Bozymski E.M., et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000;119:333-8.

8. Desai T.K., Krishnan K., Samala N., et al. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut 2012;61:970-6.

9. Ford A.C., Sandborn W.J., Khan K.J., et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644-59.

Dr. Sultan is Malcom Randall VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida

Dr. Ytter, Louis Stokes VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio

Dr. Inadomi, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Dr. Sultan and Dr. Falck-Ytter disclose are members of the GRADE working group and have been co-authors on GRADE-related publications. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

This article, by Dr. John Inadomi and colleagues is part of the AGA’s process for developing guidelines. The importance of guidelines has increased considerably over the last 25 years. In the first wave of managed care, we were practicing with few if any clinical guidelines. Now, as we move forward toward a value-based reimbursement system, the need for evidence-based practice is paramount. Dr Inadomi and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee have fine-tuned this process over the last 3 years and now describe their results. While many guidelines are labeled as "GRADE," some are simply opinion documents designed with GRADE wording. A fully implemented GRADE process involves rigorous analysis of published data, input from trained GRADE methodologists, and opportunities for both public and expert comment from all involved stakeholders.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF Special Section Editor

The economic foundation upon which U.S. health care delivery is built is shifting rapidly. Specifically, reimbursement is changing from fee for service to value-based payments. These include bundled payments for episodes of care, and payments tied to health outcomes with shared reimbursement in which payments are distributed among all stakeholders including primary care, specialty physicians, and hospital systems. Under bundled reimbursement, payments are established a priori for each episode of care, payments will be risk adjusted, and reimbursement will not increase based on the quantity of services provided. Most importantly, payment will be modified based on providers documenting their success in achieving high-quality health outcomes and patient satisfaction compared with similar facilities servicing similar patients.

We are moving rapidly to value-based reimbursement and such changes no longer require the federal government to continue transformation of the health care landscape. In 2009, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts compared costs and quality between traditional fee-for-service and a global payment system (the Alternative Quality Contract) whereby participating provider organizations assumed accountability for spending, but also received bonuses for quality.1 Geisinger Health System, an integrated delivery system comprising hospitals, outpatient facilities, and community practices including both employed and affiliated primary care and specialty physicians, now treats 20% of total physician compensation as variable and directly dependent on annual individual and group performance.2

Based on these developments, the most important issue to address is how health care quality is defined. Traditionally, metric development and validation have been the purview of administrators. It is the premise of the AGA Institute that physicians who provide services should lead efforts to define metrics by which our clinical services and health care outcomes are judged. To achieve this goal, the AGA has changed how clinical practice guidelines are constructed and has developed the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice," a coordinated program that links guidelines to clinical decision support tools, performance measures, the infrastructure by which clinicians can report their practice outcomes (the AGA Digestive Health Outcomes Registry), the Digestive Health Recognition Program, Practice Improvement Modules, and American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification. This article, the first of two that focus on the AGA’s process for guideline development, will summarize the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to determine the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations for the AGA’s guidelines.

Guideline development begins with solicitation of topics from AGA members, the AGA Council, and the AGA Clinical Practice and Quality Management Committee (CPQMC). The CPQMC, with guidance from the AGA Council, develops focused clinical questions for each guideline that are submitted to the AGA Governing Board for consideration. For topics approved by the Governing Board, the CPQMC identifies two content experts and one methods expert to author technical reviews, which represent the evidence basis for guideline recommendations. The guideline itself is written by a separate panel that is constructed to provide representation from all stakeholders involved in the care of patients related to the guideline topic.

The AGA Ethics Committee vets potential authors and guideline panel members to identify conflicts of interest and ensure transparency of the process.

GRADE

To impact medical practitioners, guidelines must be derived from well-constructed studies from which information can be derived to support clinical recommendations. Because published studies vary in their methods, comparison populations, and statistical strength, some commonly accepted process is needed so that clinicians can determine how reliable guideline recommendations would be. Currently, the most common methodology to judge strength of evidence (and hence strength of our recommendations) is the GRADE framework,3 an internationally recognized method implemented by more than 70 organizations. Importantly, this process is accepted by the National Quality Forum, which is the body responsible for vetting quality metrics that may be adopted by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services for use in enhanced reimbursement.

The goal of clinical practice guidelines is multifold; to improve patient care and health outcomes, to reduce inappropriate variations in practice, to promote efficient use of resources, and to help define and inform public policy. Although there has been an increase in the number of guidelines over the past 5 years, uptake and adoption of guidelines has been hindered by a number of factors; notably, lack of transparency, lack of a uniform system to rate evidence that informs the guideline, lack of trust in recommendations, and ineffective management of conflicts of interest. Recognizing these deficiencies, a recent Institute of Medicine report defined standards for the development of high-quality guidelines.4

GRADE’s methodologically rigorous framework and binary classification of strong vs. conditional (weak) recommendations provides a clear and actionable direction to patients, clinicians, and policy makers. A strong recommendation means that most patients should receive the recommended course of action, whereas a conditional recommendation means that different choices will be appropriate for different patients (Table 1).

Developing a guideline using GRADE

Defining the clinical question

The first step within the GRADE framework is to formulate the clinical questions to be addressed. This not only helps to define the focus of the guideline but it also outlines the criteria for the search strategy that will be used to identify the body of evidence. The clinical question should include the following four components: patient population, intervention, comparator, and outcome (PICO format).

Consider the following: does daily aspirin for chemoprevention reduce the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC)? This informal question would yield a relatively large number of studies that vary with respect to study design (observational studies vs. randomized controlled trials), patient population (patients with hereditary cancer syndromes vs. a personal history of adenomas), interventions (low-dose aspirin vs. regular-dose aspirin), comparators (aspirin vs. cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors), as well as outcomes (recurrent adenomas vs. advanced adenomas vs. cancer). A more appropriate clinical question may be the following: in average-risk patients with no prior history of CRC or adenomas, does regular-dose aspirin vs. no aspirin reduce the incidence of CRC? This latter PICO is defined more clearly and translates into a search strategy that may yield more relevant studies.

Not all outcomes are equally important

GRADE categorizes outcomes as critical for decision making, important but not critical (for decision making), and those that are less or not important for decision making. This explicit ranking of outcomes within a hierarchy is important because in GRADE the quality of evidence is determined for each outcome. This is in contrast to other systems of guideline development, in which quality is determined by study type and on a study-by-study basis. For example, in developing a guideline for stool testing for CRC, outcomes such as CRC-related mortality may be considered critical outcomes, incidence of advanced adenomas or minor procedure-related complications may be important, but not critical outcomes, and, finally, incidence of diminutive polyps may be considered less important outcomes.

A high-quality guideline requires a systematic review of the evidence

A systematic search for the evidence should be conducted or identified through sources such as the Cochrane Library or Medline. This systematic review (SR) will provide the data across individual studies used to generate a best estimate of the effect for each outcome. A guideline panel can conduct its own SR or use an existing SR that is deemed to be of sufficient quality.

Grading the quality of the evidence

GRADE defines quality as the extent to which our confidence in an estimate of the treatment effect is adequate to support a particular recommendation. The GRADE system specifies four grades of confidence in the evidence: high, moderate, low, and very low. Explicit criteria are available for rating down or rating up the quality of evidence. Evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) start with a high confidence in the evidence, whereas an initial low confidence in the estimate is typical for evidence from observational studies (Table 1).

If an RCT has major methodologic limitations such as inadequate allocation concealment, lack of blinding, lack of accounting for high losses to follow-up evaluation, failure to perform an intention-to-treat analysis, selective reporting of outcomes, and stopping early for benefit, this may lower the quality of the evidence. In a recent meta-analysis comparing proton pump inhibitor therapy vs. histamine2-receptor antagonists in critically ill patients at risk for stress-related mucosal bleeding, significant methodologic issues, including lack of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, as well as high loss to follow-up evaluation, were recognized.5 The meta-analysis found less gastrointestinal bleeding among those who received proton pump inhibitors (1.3% vs. 6.6%; odds ratio, 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.54), however, because of the many study limitations, we might consider rating down this body of evidence from high to moderate.

If an issue has inconsistent results, this refers to wide variability of treatment effects across individual studies. When variability in treatment effects is seen, it is important to try to identify the explanations for these inconsistent results; many times this variability may be explained by differences in populations, differences in the intervention, difference in outcome measures, or differences in study methodology. When no explanation for the inconsistency in results is identified, this may lower our confidence in the estimate of effect across the body of evidence.

More often than not, direct comparisons of interventions (e.g., how does fecal immunochemical testing compare with colonoscopy in reducing CRC mortality?) are unavailable, introducing uncertainty of comparative effectiveness. In addition, the existing body of evidence may differ with respect to the population, intervention, or outcome as it relates to a specific clinical question.

When studies include few patients or few events, the estimates of effect have wide confidence intervals that include benefit and no effect, or even potentially harm. In a systematic review on the use of thiopurines vs. placebo for induction of remission in adults with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, the pooled estimate from five RCTs showed a relative risk of 0.87 (95% confidence interval, 0.71-1.06) for the outcome of failure of remission, with the lower boundary of the 95% confidence interval suggesting a close to 30% benefit, but the upper boundary failing to show an effect.6 Although the pooled estimate suggests that thiopurines are beneficial, our confidence in the result is reduced because of imprecision.

Publication bias is another factor that can result in a rating down of the quality of the evidence. Often this is attributed to a lack of reporting of small studies and/or studies showing no benefit. For example, a meta-analysis of 27 publications on estimates of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus showed an inverse relationship between study size and cancer risk, suggesting publication bias and an overestimation of the risk of developing esophageal cancer (0.5% per year).7 A subsequent meta-analysis of 57 studies (11,434 patients and 58,547 patient-years of follow-up evaluation) showed a lower pooled annual risk of 0.3% per year.8

Although evidence from observational studies starts out as low-quality evidence, rating up the quality of evidence may be appropriate in specific circumstances. For example, average-risk screening colonoscopy reduces the risk of CRC mortality but the risk of colonoscopy-related splenic rupture is less clear because only case reports are available. However, as the incidence of splenic rupture in the population not screened with colonoscopy approaches zero, the resulting estimate of relative effect for splenic rupture as a result of colonoscopy is likely large, increasing our confidence in the estimate of the adverse event (Table 1).

Outcomes critical for decision making determine the overall quality of evidence

Because competing management strategies will have both beneficial outcomes as well as undesirable effects, basing the overall quality of evidence for a recommendation solely on the beneficial outcomes would be inappropriate. For example, although there is higher-quality evidence from a meta-analysis of natalizumab in reducing the risk of failure to achieve remission in Crohn’s disease,9 the overall quality of evidence should be based on the lower quality of evidence for harm (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), as long as the occurrence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy was considered critical for decision making by the guideline panel.

Making recommendations

Although the overall quality of evidence across outcomes is the defining starting point for guideline construction, additional factors, such as the balance between desirable and undesirable effects and patients’ values and preferences, need explicit considerations and may change the strength, and even the direction, of recommendations. Finally, the uncertainty of whether the recommended course of action represents a wise use of resources may need consideration depending on the perspective of the guideline panel (Table 1).

Conclusions

The GRADE process is an internationally recognized method by which clinical practice guidelines may be developed taking into account not only the quality of the evidence surrounding a specific PICO question, but also the relative benefits and harms associated with competing management strategies, potential ambiguity in patient preferences for treatments and outcomes, and the health care resources necessary to implement interventions or strategies.

The ultimate goal is the creation of clinical practice guidelines that are based on the best existing evidence, are transparent in their construction, provide clear guidance to practicing physicians, and form the basis of metrics upon which we agree to be judged. The latter is what will be required of us going forward: documentation that we are delivering high-quality health care that is proven to improve the outcomes of patients. When we achieve these goals we should be rewarded appropriately. The AGA GRADE process will ensure that gastroenterologists remain in charge of our own destiny, and that we define the optimal manner in which to care for our patients.

References

1. Song Z., Safran D.G., Landon B.E., et al. Health care spending and quality in year 1 of the alternative quality contract . N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:909-18.

2. Lee T.H., Bothe A., Steele G.D. How Geisinger structures its physicians’ compensation to support improvements in quality, efficiency, and volume. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2068-73.

3. Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6.

4. In: Graham R., Mancher M., Wolman D.M., et al. editors. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

5. Barkun A.N., Bardou M., Pham C.Q., et al. Proton pump inhibitors vs. histamine 2 receptor antagonists for stress-related mucosal bleeding prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012;107:507-20.

6. Khan K.J., Dubinsky M.C., Ford A.C., et al. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:630-42.

7. Shaheen N.J., Crosby M.A., Bozymski E.M., et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000;119:333-8.

8. Desai T.K., Krishnan K., Samala N., et al. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut 2012;61:970-6.

9. Ford A.C., Sandborn W.J., Khan K.J., et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644-59.

Dr. Sultan is Malcom Randall VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida

Dr. Ytter, Louis Stokes VA Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio

Dr. Inadomi, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Dr. Sultan and Dr. Falck-Ytter disclose are members of the GRADE working group and have been co-authors on GRADE-related publications. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.