User login

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

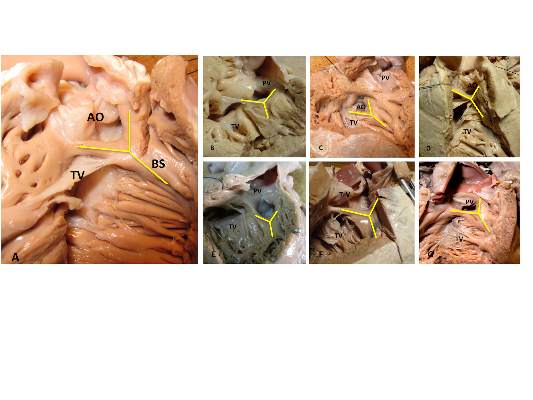

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: The presence of a fibrous continuity at the postinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment.

Major finding: The outlet VSD is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD.

Data source: The researchers examined 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.