User login

Intrauterine exposure to methylphenidate tied to increased cardiac risk

The use of methylphenidate by pregnant women is associated with a small increased risk of congenital cardiac malformations in newborns. However, a comparable increased risk is not found with intrauterine exposure to stimulants, according to a population-based cohort study published Dec. 13.

Krista F. Huybrechts, PhD, and her associates analyzed data from more than 1 million pregnancies in the United States. They found that the overall incidence of congenital malformations among the 1,813,894 pregnancies was 35 per 1,000 control infants, compared with 45.9 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used methylphenidate and 45.4 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used amphetamines.

For the subset of infants with cardiac malformations, the risk per 1,000 infants was 12.7 for controls, 18.8 for methylphenidate exposure, and 15.4 for amphetamine exposure. The researchers identified an adjusted relative risk of 1.11 for overall congenital abnormalities and 1.28 for cardiac abnormalities with methylphenidate exposure, compared with a relative risk of 1.05 for overall congenital abnormalities and 0.96 for cardiac abnormalities with stimulant exposure.

An analysis among 2,560,069 pregnancies in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden yielded a similarly significant relative risk of 1.28 for cardiac malformations associated with methylphenidate exposure (JAMA Psychiatry 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3644).

“We found a 28% increased prevalence of cardiac malformations after first-trimester exposure to methylphenidate,” wrote Dr. Huybrechts of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. “Although the absolute risk is small, it is nevertheless important evidence to consider when weighing the potential risks and benefits of different treatment strategies for [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder] in young women of reproductive age and in pregnant women.”

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development, and the Söderström König Foundation.

The use of methylphenidate by pregnant women is associated with a small increased risk of congenital cardiac malformations in newborns. However, a comparable increased risk is not found with intrauterine exposure to stimulants, according to a population-based cohort study published Dec. 13.

Krista F. Huybrechts, PhD, and her associates analyzed data from more than 1 million pregnancies in the United States. They found that the overall incidence of congenital malformations among the 1,813,894 pregnancies was 35 per 1,000 control infants, compared with 45.9 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used methylphenidate and 45.4 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used amphetamines.

For the subset of infants with cardiac malformations, the risk per 1,000 infants was 12.7 for controls, 18.8 for methylphenidate exposure, and 15.4 for amphetamine exposure. The researchers identified an adjusted relative risk of 1.11 for overall congenital abnormalities and 1.28 for cardiac abnormalities with methylphenidate exposure, compared with a relative risk of 1.05 for overall congenital abnormalities and 0.96 for cardiac abnormalities with stimulant exposure.

An analysis among 2,560,069 pregnancies in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden yielded a similarly significant relative risk of 1.28 for cardiac malformations associated with methylphenidate exposure (JAMA Psychiatry 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3644).

“We found a 28% increased prevalence of cardiac malformations after first-trimester exposure to methylphenidate,” wrote Dr. Huybrechts of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. “Although the absolute risk is small, it is nevertheless important evidence to consider when weighing the potential risks and benefits of different treatment strategies for [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder] in young women of reproductive age and in pregnant women.”

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development, and the Söderström König Foundation.

The use of methylphenidate by pregnant women is associated with a small increased risk of congenital cardiac malformations in newborns. However, a comparable increased risk is not found with intrauterine exposure to stimulants, according to a population-based cohort study published Dec. 13.

Krista F. Huybrechts, PhD, and her associates analyzed data from more than 1 million pregnancies in the United States. They found that the overall incidence of congenital malformations among the 1,813,894 pregnancies was 35 per 1,000 control infants, compared with 45.9 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used methylphenidate and 45.4 per 1,000 infants whose mothers used amphetamines.

For the subset of infants with cardiac malformations, the risk per 1,000 infants was 12.7 for controls, 18.8 for methylphenidate exposure, and 15.4 for amphetamine exposure. The researchers identified an adjusted relative risk of 1.11 for overall congenital abnormalities and 1.28 for cardiac abnormalities with methylphenidate exposure, compared with a relative risk of 1.05 for overall congenital abnormalities and 0.96 for cardiac abnormalities with stimulant exposure.

An analysis among 2,560,069 pregnancies in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden yielded a similarly significant relative risk of 1.28 for cardiac malformations associated with methylphenidate exposure (JAMA Psychiatry 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3644).

“We found a 28% increased prevalence of cardiac malformations after first-trimester exposure to methylphenidate,” wrote Dr. Huybrechts of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. “Although the absolute risk is small, it is nevertheless important evidence to consider when weighing the potential risks and benefits of different treatment strategies for [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder] in young women of reproductive age and in pregnant women.”

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Mental Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development, and the Söderström König Foundation.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Heart surgery halves in-hospital mortality in trisomy 13 and 18

For infants with trisomy 13 or trisomy 18, congenital heart surgery is associated with a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality, according to results of a large, retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

In-hospital mortality was 45% lower in trisomy 13 patients (P = .003) and 64% lower in trisomy 18 patients (P less than.001) who underwent surgery, data show (Pediatrics 140(5); 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0772).

The study, based on records from the 44 participating children’s hospitals represented in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, included 1,668 newborns with trisomy 13 or 18 who were admitted within 14 days of birth. Median age at admission was less than 1 day for both groups.

Congenital heart disease was present in 925 out of 1,020 infants with trisomy 18 (91%) and 555 out of 648 with trisomy 13 (86%), the report stated.

For those infants with congenital heart disease, overall mortality was highest during the first hospital admission (63%), investigators wrote. However, for those undergoing congenital heart surgery, multivariate analysis showed decreased in-hospital mortality vs. those who had no surgery for both the trisomy 13 (30% vs. 55%, respectively, P = .003) and the trisomy 18 groups (16% vs. 44%, P less than .001).

This is not only the largest-ever study of trisomy 13 and 18 ever reported, according to the investigators, but also the first to show that higher weight, female sex, and older age at admission are associated with improved survival following congenital heart surgery among these patients. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed significant effects of these risk factors on mortality for both the trisomy 13 and 18 infant subsets, according to Dr. Kosiv and her colleagues.

These findings come at a time when many centers elect not to perform congenital heart surgery in trisomy 13 and 18 patients, the investigators wrote, noting that management is typically limited to medical strategies due to the “markedly short life expectancy” and grave prognosis associated with the condition.

Mortality was markedly decreased, but still considerably higher than what would be expected for congenital heart surgery in the general population, which is an important consideration for families and practitioners who are considering the procedure, investigators said in their report.

Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that “CHS may not be futile, at least not in the short-term, in patients with T13 and T18,” Dr. Kosiv and colleagues wrote. “Additionally, these results suggest that CHS may allow families to be able to take their children home and avoid [them] dying in the hospital.”

The article by Kosiv and colleagues provides “compelling evidence that congenital heart surgery can be considered” in infants with trisomy 13 or 18, according Kathy J. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Amy E. Roberts, MD in their accompanying editorial. The decision, however, should be made as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, they said.

“In our view, this should only occur when parents are fully informed of the still significant residual infant mortality risk with cardiac surgery … and unavoidable, severe neurocognitive delays,” they wrote in their editorial.

Caregivers helping families make the decision, they added, should be aware that delays in decision-making might make operations impossible or even more risky than they already are.

“The revolution in congenital heart surgery … has now changed the equation for infants with trisomy 18 and 13 just as it did for trisomy 21 in the past,” the authors wrote. “However, numerous factors must be taken into account to optimize decision-making for each infant and family.”

Dr. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Dr. Roberts, MD are with the Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. These comments are based on their editorial (Pediatrics 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2809). The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

The article by Kosiv and colleagues provides “compelling evidence that congenital heart surgery can be considered” in infants with trisomy 13 or 18, according Kathy J. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Amy E. Roberts, MD in their accompanying editorial. The decision, however, should be made as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, they said.

“In our view, this should only occur when parents are fully informed of the still significant residual infant mortality risk with cardiac surgery … and unavoidable, severe neurocognitive delays,” they wrote in their editorial.

Caregivers helping families make the decision, they added, should be aware that delays in decision-making might make operations impossible or even more risky than they already are.

“The revolution in congenital heart surgery … has now changed the equation for infants with trisomy 18 and 13 just as it did for trisomy 21 in the past,” the authors wrote. “However, numerous factors must be taken into account to optimize decision-making for each infant and family.”

Dr. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Dr. Roberts, MD are with the Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. These comments are based on their editorial (Pediatrics 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2809). The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

The article by Kosiv and colleagues provides “compelling evidence that congenital heart surgery can be considered” in infants with trisomy 13 or 18, according Kathy J. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Amy E. Roberts, MD in their accompanying editorial. The decision, however, should be made as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, they said.

“In our view, this should only occur when parents are fully informed of the still significant residual infant mortality risk with cardiac surgery … and unavoidable, severe neurocognitive delays,” they wrote in their editorial.

Caregivers helping families make the decision, they added, should be aware that delays in decision-making might make operations impossible or even more risky than they already are.

“The revolution in congenital heart surgery … has now changed the equation for infants with trisomy 18 and 13 just as it did for trisomy 21 in the past,” the authors wrote. “However, numerous factors must be taken into account to optimize decision-making for each infant and family.”

Dr. Jenkins, MD, MPH, and Dr. Roberts, MD are with the Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. These comments are based on their editorial (Pediatrics 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2809). The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

For infants with trisomy 13 or trisomy 18, congenital heart surgery is associated with a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality, according to results of a large, retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

In-hospital mortality was 45% lower in trisomy 13 patients (P = .003) and 64% lower in trisomy 18 patients (P less than.001) who underwent surgery, data show (Pediatrics 140(5); 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0772).

The study, based on records from the 44 participating children’s hospitals represented in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, included 1,668 newborns with trisomy 13 or 18 who were admitted within 14 days of birth. Median age at admission was less than 1 day for both groups.

Congenital heart disease was present in 925 out of 1,020 infants with trisomy 18 (91%) and 555 out of 648 with trisomy 13 (86%), the report stated.

For those infants with congenital heart disease, overall mortality was highest during the first hospital admission (63%), investigators wrote. However, for those undergoing congenital heart surgery, multivariate analysis showed decreased in-hospital mortality vs. those who had no surgery for both the trisomy 13 (30% vs. 55%, respectively, P = .003) and the trisomy 18 groups (16% vs. 44%, P less than .001).

This is not only the largest-ever study of trisomy 13 and 18 ever reported, according to the investigators, but also the first to show that higher weight, female sex, and older age at admission are associated with improved survival following congenital heart surgery among these patients. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed significant effects of these risk factors on mortality for both the trisomy 13 and 18 infant subsets, according to Dr. Kosiv and her colleagues.

These findings come at a time when many centers elect not to perform congenital heart surgery in trisomy 13 and 18 patients, the investigators wrote, noting that management is typically limited to medical strategies due to the “markedly short life expectancy” and grave prognosis associated with the condition.

Mortality was markedly decreased, but still considerably higher than what would be expected for congenital heart surgery in the general population, which is an important consideration for families and practitioners who are considering the procedure, investigators said in their report.

Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that “CHS may not be futile, at least not in the short-term, in patients with T13 and T18,” Dr. Kosiv and colleagues wrote. “Additionally, these results suggest that CHS may allow families to be able to take their children home and avoid [them] dying in the hospital.”

For infants with trisomy 13 or trisomy 18, congenital heart surgery is associated with a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality, according to results of a large, retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

In-hospital mortality was 45% lower in trisomy 13 patients (P = .003) and 64% lower in trisomy 18 patients (P less than.001) who underwent surgery, data show (Pediatrics 140(5); 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0772).

The study, based on records from the 44 participating children’s hospitals represented in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, included 1,668 newborns with trisomy 13 or 18 who were admitted within 14 days of birth. Median age at admission was less than 1 day for both groups.

Congenital heart disease was present in 925 out of 1,020 infants with trisomy 18 (91%) and 555 out of 648 with trisomy 13 (86%), the report stated.

For those infants with congenital heart disease, overall mortality was highest during the first hospital admission (63%), investigators wrote. However, for those undergoing congenital heart surgery, multivariate analysis showed decreased in-hospital mortality vs. those who had no surgery for both the trisomy 13 (30% vs. 55%, respectively, P = .003) and the trisomy 18 groups (16% vs. 44%, P less than .001).

This is not only the largest-ever study of trisomy 13 and 18 ever reported, according to the investigators, but also the first to show that higher weight, female sex, and older age at admission are associated with improved survival following congenital heart surgery among these patients. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed significant effects of these risk factors on mortality for both the trisomy 13 and 18 infant subsets, according to Dr. Kosiv and her colleagues.

These findings come at a time when many centers elect not to perform congenital heart surgery in trisomy 13 and 18 patients, the investigators wrote, noting that management is typically limited to medical strategies due to the “markedly short life expectancy” and grave prognosis associated with the condition.

Mortality was markedly decreased, but still considerably higher than what would be expected for congenital heart surgery in the general population, which is an important consideration for families and practitioners who are considering the procedure, investigators said in their report.

Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that “CHS may not be futile, at least not in the short-term, in patients with T13 and T18,” Dr. Kosiv and colleagues wrote. “Additionally, these results suggest that CHS may allow families to be able to take their children home and avoid [them] dying in the hospital.”

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Despite many centers choosing not to perform congenital heart surgery in infants with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18, doing so cuts in-hospital mortality by more than half.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality was 45% lower in trisomy 13 patients (P = 0.003) and 64% lower in trisomy 18 patients (P < 0.001) who underwent surgery.

Data source: A large, retrospective, multicenter cohort study of 1,668 newborns with trisomy 13 or 18 admitted within 14 days of birth.

Disclosures: The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Why VADS is gaining ground in pediatrics

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Advances in continuous-flow ventricular assist devices (VADs) promise a paradigm shift in pediatrics.

Major finding: Device miniaturization is solving problems such as size mismatch, inpatients on VADs, and chronic therapy.

Data source: Expert opinion drawing on PediMACS reports and published trials of continuous-flow VAD.

Disclosures: Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

Can arterial switch operation impact cognitive deficits?

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of young adults who had transposition of the great arteries have cognitive or psychological difficulties.

Major finding: Cognitive difficulties were significantly more frequent in the study population than the general population, 31% vs. 16%.

Data source: Age-, gender-, and education level–matched population of 67 young adults with transposition of the great arteries and 43 healthy subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

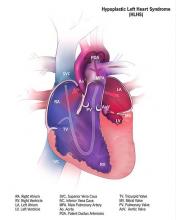

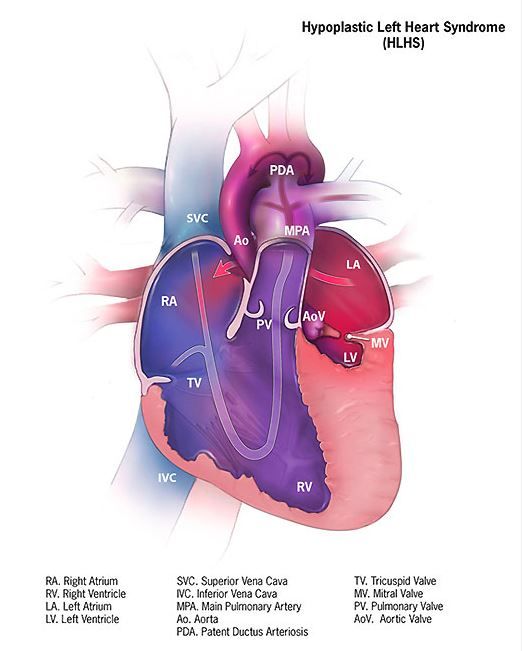

Cerebral NIRS may be flawed for assessing infant brains after stage 1 palliation of HLHS

The regional oxygenation index (rSO2) based on near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurement is frequently used to assess the adequacy of oxygen delivery after stage 1 palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). However, a recent study showed that cerebral rSO2 has low sensitivity and should not be considered reassuring even at rSO2 of 50 or greater. In addition, values below 30 were not found to be sensitive for detecting compromised oxygen delivery, according to a report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Erin Rescoe, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues at Harvard Medical School, Boston, performed a retrospective study of 73 neonates assessed with cerebral venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (ScvO2) measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein, which is considered the preferred method for assessing the adequacy of tissue oxygen delivery, compared with cerebral rSO2 after stage 1 palliation of HLHS (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.154).

To determine the suggested benefit of NIRS as an effective trend monitor, the researchers used their interpolated data to examine changes in rSO2 and changes in ScvO2 at hourly intervals and compared these values.Of particular concern is the result showing that, in all instances where ScvO2 was less than 30%, rSO2 was greater than 30%. In terms of the sensitivity (the true positive rate) and specificity (the true negative rate) of using NIRS, time-matched pairs of rSO2 and ScvO2 showed that the receiver operating characteristic curves for rSO2 as a diagnostic test to detect ScvO2 less than 30%, less than 40%, and less than 50% were 0.82, 0.84, and 0.87, respectively, showing good specificity, with a value of rSO2 less than 30% indicating that ScvO2 will be less than 30% 99% of the time.

“However, the sensitivity of rSO2 in the range of clinical interest in detecting ScvO2 less than 30% is extremely low,” according to the researchers. Thus, NIRS is likely to produce false negatives, missing patients with clinically low postoperative oxygen saturation.

In fact, rSO2 was less than 30% less than 1% of the time that ScvO2 was less than 30%. Similar results were seen in comparing values at the less than 40% mark (equivalent less than 1% of the time). Better results showed at the less than 50% mark, with equivalence seen 46% of the time.

NIRS measures a composite of arterial and venous blood, according to Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues. Therefore, to do a more direct comparison, they adjusted their NIRS results by calculating an rSO2-based ScvO2 designed to remove arterial contamination from the rSO2 signal: rSO2-based ScvO2 = (rSO2 arterial oxygen saturation x 0.3)/0.7.

This significantly improved the sensitivity of rSO2 to detect ScvO2 at less than 30% to 6.5%, to 29% for rSO2 at less than 40%, and 77.4% for rSO2 less than 50%.

The researchers “were surprised by the extremely low sensitivity of cerebral NIRS to detect even the most severe aberrations in DO2” (i.e., ScvO2 less than 30%, which has been found to be associated with poor outcomes).

“Cerebral rSO2 in isolation should not be used to detect low ScvO2, because its sensitivity is low, although correction of rSO2 for arterial contamination significantly improves sensitivity. Cerebral rSO2 of 50 or greater should not be considered reassuring with regard to ScvO2, although values less than 30 are specific for low ScvO2,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Gerber Foundation, the Hess Family Philanthropic Fund, and Boston Children’s Hospital Heart Center Strategic Investment Fund. The authors disclosed that they had no financial conflicts.

The use of postoperative cerebral venous oxygen saturation monitoring (ScvO2) through an internal jugular vein catheter allows better monitoring of circulation, which may lead to better outcomes, but it is invasive and challenging. NIRS, being noninvasive, has proved attractive, but clinical interpretation in terms of both absolute values and trends is difficult, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and his colleagues noted in their invited commentary (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.04.061).

Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues have analyzed the correlation of NIRS-derived data with ScvO2 measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein in 73 neonates after stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. They demonstrated that cerebral rSO2 correlated poorly with low ScvO2, and they suggest that cerebral rSO2 not be used in isolation. This problem was somewhat ameliorated by correction of the signal for arterial contamination. NIRS appears to be too valuable a tool to be simply discarded, they said, suggesting that a perioperative risk assessment that would include multisite NIRS and hemodynamic monitoring might still allow early determination of low-cardiac output.

“Two numbers are better than one,” wrote Dr. Buratto and his colleagues. “Whether the NIRS technology will add any useful information to a simple bedside assessment by an astute clinician is yet to be seen.”

Edward Buratto, MBBS, Steve Horton, PhD, and Igor E. Konstantinov, MD, are from the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital; the Department of Pediatrics, University of Melbourne; and Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne. They reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

The use of postoperative cerebral venous oxygen saturation monitoring (ScvO2) through an internal jugular vein catheter allows better monitoring of circulation, which may lead to better outcomes, but it is invasive and challenging. NIRS, being noninvasive, has proved attractive, but clinical interpretation in terms of both absolute values and trends is difficult, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and his colleagues noted in their invited commentary (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.04.061).

Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues have analyzed the correlation of NIRS-derived data with ScvO2 measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein in 73 neonates after stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. They demonstrated that cerebral rSO2 correlated poorly with low ScvO2, and they suggest that cerebral rSO2 not be used in isolation. This problem was somewhat ameliorated by correction of the signal for arterial contamination. NIRS appears to be too valuable a tool to be simply discarded, they said, suggesting that a perioperative risk assessment that would include multisite NIRS and hemodynamic monitoring might still allow early determination of low-cardiac output.

“Two numbers are better than one,” wrote Dr. Buratto and his colleagues. “Whether the NIRS technology will add any useful information to a simple bedside assessment by an astute clinician is yet to be seen.”

Edward Buratto, MBBS, Steve Horton, PhD, and Igor E. Konstantinov, MD, are from the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital; the Department of Pediatrics, University of Melbourne; and Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne. They reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

The use of postoperative cerebral venous oxygen saturation monitoring (ScvO2) through an internal jugular vein catheter allows better monitoring of circulation, which may lead to better outcomes, but it is invasive and challenging. NIRS, being noninvasive, has proved attractive, but clinical interpretation in terms of both absolute values and trends is difficult, Edward Buratto, MBBS, and his colleagues noted in their invited commentary (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.04.061).

Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues have analyzed the correlation of NIRS-derived data with ScvO2 measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein in 73 neonates after stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. They demonstrated that cerebral rSO2 correlated poorly with low ScvO2, and they suggest that cerebral rSO2 not be used in isolation. This problem was somewhat ameliorated by correction of the signal for arterial contamination. NIRS appears to be too valuable a tool to be simply discarded, they said, suggesting that a perioperative risk assessment that would include multisite NIRS and hemodynamic monitoring might still allow early determination of low-cardiac output.

“Two numbers are better than one,” wrote Dr. Buratto and his colleagues. “Whether the NIRS technology will add any useful information to a simple bedside assessment by an astute clinician is yet to be seen.”

Edward Buratto, MBBS, Steve Horton, PhD, and Igor E. Konstantinov, MD, are from the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital; the Department of Pediatrics, University of Melbourne; and Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne. They reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

The regional oxygenation index (rSO2) based on near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurement is frequently used to assess the adequacy of oxygen delivery after stage 1 palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). However, a recent study showed that cerebral rSO2 has low sensitivity and should not be considered reassuring even at rSO2 of 50 or greater. In addition, values below 30 were not found to be sensitive for detecting compromised oxygen delivery, according to a report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Erin Rescoe, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues at Harvard Medical School, Boston, performed a retrospective study of 73 neonates assessed with cerebral venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (ScvO2) measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein, which is considered the preferred method for assessing the adequacy of tissue oxygen delivery, compared with cerebral rSO2 after stage 1 palliation of HLHS (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.154).

To determine the suggested benefit of NIRS as an effective trend monitor, the researchers used their interpolated data to examine changes in rSO2 and changes in ScvO2 at hourly intervals and compared these values.Of particular concern is the result showing that, in all instances where ScvO2 was less than 30%, rSO2 was greater than 30%. In terms of the sensitivity (the true positive rate) and specificity (the true negative rate) of using NIRS, time-matched pairs of rSO2 and ScvO2 showed that the receiver operating characteristic curves for rSO2 as a diagnostic test to detect ScvO2 less than 30%, less than 40%, and less than 50% were 0.82, 0.84, and 0.87, respectively, showing good specificity, with a value of rSO2 less than 30% indicating that ScvO2 will be less than 30% 99% of the time.

“However, the sensitivity of rSO2 in the range of clinical interest in detecting ScvO2 less than 30% is extremely low,” according to the researchers. Thus, NIRS is likely to produce false negatives, missing patients with clinically low postoperative oxygen saturation.

In fact, rSO2 was less than 30% less than 1% of the time that ScvO2 was less than 30%. Similar results were seen in comparing values at the less than 40% mark (equivalent less than 1% of the time). Better results showed at the less than 50% mark, with equivalence seen 46% of the time.

NIRS measures a composite of arterial and venous blood, according to Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues. Therefore, to do a more direct comparison, they adjusted their NIRS results by calculating an rSO2-based ScvO2 designed to remove arterial contamination from the rSO2 signal: rSO2-based ScvO2 = (rSO2 arterial oxygen saturation x 0.3)/0.7.

This significantly improved the sensitivity of rSO2 to detect ScvO2 at less than 30% to 6.5%, to 29% for rSO2 at less than 40%, and 77.4% for rSO2 less than 50%.

The researchers “were surprised by the extremely low sensitivity of cerebral NIRS to detect even the most severe aberrations in DO2” (i.e., ScvO2 less than 30%, which has been found to be associated with poor outcomes).

“Cerebral rSO2 in isolation should not be used to detect low ScvO2, because its sensitivity is low, although correction of rSO2 for arterial contamination significantly improves sensitivity. Cerebral rSO2 of 50 or greater should not be considered reassuring with regard to ScvO2, although values less than 30 are specific for low ScvO2,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Gerber Foundation, the Hess Family Philanthropic Fund, and Boston Children’s Hospital Heart Center Strategic Investment Fund. The authors disclosed that they had no financial conflicts.

The regional oxygenation index (rSO2) based on near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurement is frequently used to assess the adequacy of oxygen delivery after stage 1 palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). However, a recent study showed that cerebral rSO2 has low sensitivity and should not be considered reassuring even at rSO2 of 50 or greater. In addition, values below 30 were not found to be sensitive for detecting compromised oxygen delivery, according to a report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

Erin Rescoe, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and her colleagues at Harvard Medical School, Boston, performed a retrospective study of 73 neonates assessed with cerebral venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (ScvO2) measured by co-oximetry from the internal jugular vein, which is considered the preferred method for assessing the adequacy of tissue oxygen delivery, compared with cerebral rSO2 after stage 1 palliation of HLHS (doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.154).

To determine the suggested benefit of NIRS as an effective trend monitor, the researchers used their interpolated data to examine changes in rSO2 and changes in ScvO2 at hourly intervals and compared these values.Of particular concern is the result showing that, in all instances where ScvO2 was less than 30%, rSO2 was greater than 30%. In terms of the sensitivity (the true positive rate) and specificity (the true negative rate) of using NIRS, time-matched pairs of rSO2 and ScvO2 showed that the receiver operating characteristic curves for rSO2 as a diagnostic test to detect ScvO2 less than 30%, less than 40%, and less than 50% were 0.82, 0.84, and 0.87, respectively, showing good specificity, with a value of rSO2 less than 30% indicating that ScvO2 will be less than 30% 99% of the time.

“However, the sensitivity of rSO2 in the range of clinical interest in detecting ScvO2 less than 30% is extremely low,” according to the researchers. Thus, NIRS is likely to produce false negatives, missing patients with clinically low postoperative oxygen saturation.

In fact, rSO2 was less than 30% less than 1% of the time that ScvO2 was less than 30%. Similar results were seen in comparing values at the less than 40% mark (equivalent less than 1% of the time). Better results showed at the less than 50% mark, with equivalence seen 46% of the time.

NIRS measures a composite of arterial and venous blood, according to Dr. Rescoe and her colleagues. Therefore, to do a more direct comparison, they adjusted their NIRS results by calculating an rSO2-based ScvO2 designed to remove arterial contamination from the rSO2 signal: rSO2-based ScvO2 = (rSO2 arterial oxygen saturation x 0.3)/0.7.

This significantly improved the sensitivity of rSO2 to detect ScvO2 at less than 30% to 6.5%, to 29% for rSO2 at less than 40%, and 77.4% for rSO2 less than 50%.

The researchers “were surprised by the extremely low sensitivity of cerebral NIRS to detect even the most severe aberrations in DO2” (i.e., ScvO2 less than 30%, which has been found to be associated with poor outcomes).

“Cerebral rSO2 in isolation should not be used to detect low ScvO2, because its sensitivity is low, although correction of rSO2 for arterial contamination significantly improves sensitivity. Cerebral rSO2 of 50 or greater should not be considered reassuring with regard to ScvO2, although values less than 30 are specific for low ScvO2,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Gerber Foundation, the Hess Family Philanthropic Fund, and Boston Children’s Hospital Heart Center Strategic Investment Fund. The authors disclosed that they had no financial conflicts.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In terms of sensitivity, rSO2 was less than 30% less than 1% of the time that ScvO2 was less than 30%.

Data source: A retrospective single institution study of 73 neonates assessed after stage 1 palliation

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Gerber Foundation, the Hess Family Philanthropic Fund, and Boston Children’s Hospital Heart Center Strategic Investment Fund. The authors disclosed that they had no financial conflicts.

MV disease in children requires modified strategies

NEW YORK – Repairing mitral valves in pediatric patients must overcome two issues: the wide variability in their anatomy and their growth. Using strategies and techniques common in adult mitral surgery can accomplish good mitral valve function in children, but some techniques in children differ, like using combined resorbable material with autologous tissue or transferring native chords instead of placing artificial chords to a malfunctioning leaflet.

Pedro del Nido, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, said the spectrum of mitral valve pathology in children goes from congenital mitral stenosis with a thick annulus with leaflet immobility to leaflet hypermobility that involves anterior leaflet prolapse and can involve a cleft that causes regurgitation. Dr. del Nido explained his surgical approaches for mitral valve disease in children at the 2017 Mitral Conclave, sponsored by the American Association of Thoracic Surgery.

Accessing the mitral valve in children requires a different approach than in adults, Dr. del Nido said. “Going through the left atrium is generally difficult, so we often enter through a trans-septal incision,” he said. “The main reason for that is because the tricuspid valve is often associated with the mitral valve problem and this gives us the most direct exposure.”

Once the surgeon gains exposure, the surgical analysis for a diseased adult or child valve is almost identical, with the exception that adult disease is acquired whereas childhood disease tends to be congenital, Dr. del Nido said. “In the congenital patient, we often find fibroelastic tissue that the child is born with,” he said. “We see this in neonates and young infants. It thickens over time; it doesn’t often calcify, but it does often restrict the leaflets and it tends to fuse the chords, so in essence you have direct attachments of the leaflets to the papillaries.”

He explained that this pathology requires an approach similar to that for rheumatic mitral disease in adults. “Start splitting the commissures and start resecting the tissue off the chords creating fenestrations in order to improve the inflow.” Dr. del Nido added, “If you don’t do this, the child will always have a gradient, and if you think about an adult having problems and symptoms with a gradient, think about a 10-year-old running around trying to do athletics; it’s impossible.”

Dysfunctional chords also require a somewhat different approach in children than they require in adults. “We find elongation of the chords and the anterior support structure is abnormal; the secondary chords are totally intact,” Dr. del Nido said. When confronting a torn-edge chord, resection is often an option in adults, but is uncommon in children. “We don’t usually have very much leaflet tissue,” he said. Artificial chords do not accommodate growth.

“We tend to use native tissue,” said Dr. del Nido. “You can transfer the strut chord; you can transfer the secondary chord in order to achieve support for the edge of that prolapsed leaflet.”

Leaflet problems are probably the biggest single source of recurrence in children, Dr. del Nido said. A cleft on the anterior leaflet can be particularly vexing. For example, cleft edges attached to the septum can prevent the valve leaflet from coaptation with the posterior leaflet. “If you don’t recognize that on 3-D echocardiography, you’re going to have a problem; that leaflet will never create the coaptation surface that you want,” he said.

The solution may lie underneath the leaflet. Said Dr. del Nido, “We tend to want to close a cleft, and, yes, that will get you relief of regurgitation in the central portion, but if you end up with immobility of that leaflet, then look underneath. Most often there are very abnormal attachments to the edges of that cleft to the septum. You have to get rid of that; if you don’t resect all that, you’ll never have a leaflet that truly floats up to coapt against the posterior leaflet.”

Annular dilation in children can also challenge a cardiothoracic surgeon’s skill.

In rare cases, a suture commissuroplasty may correct the problem. Sometimes Dr. del Nido will use the DeVega suture annuloplasty – “even though it is very much user dependent; it’s very easy in pediatrics to create stenosis with the DeVega.” As an alternative, synthetic ring annuloplasties can confine valve growth and are rarely used.

Dr. del Nido’s preference is to use a hybrid approach of tissue and resorbable material. “The advantage of the resorbable material is that it will go away, but that’s also the problem with the resorbable material,” he said. “Once it does go away, there’s nothing there to support the annulus, so a combination of tissue and resorbable suture is probably the best answer.”

In posterior leaflet deficiency, a patch of pericardium posteriorly can augment the dysfunctional leaflet. You can also use pericardium as an annuloplasty ring. “You can use it circumferentially,” Dr. del Nido said. “It’s a soft ring; you can certainly use this material which is autologous; it does provide strength to the fibrous annulus; it does support that valve; and you do see growth.” He added that bovine pericardium is not ideal for this use.

Dr. del Nido reported no relevant financial relationships.

NEW YORK – Repairing mitral valves in pediatric patients must overcome two issues: the wide variability in their anatomy and their growth. Using strategies and techniques common in adult mitral surgery can accomplish good mitral valve function in children, but some techniques in children differ, like using combined resorbable material with autologous tissue or transferring native chords instead of placing artificial chords to a malfunctioning leaflet.

Pedro del Nido, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, said the spectrum of mitral valve pathology in children goes from congenital mitral stenosis with a thick annulus with leaflet immobility to leaflet hypermobility that involves anterior leaflet prolapse and can involve a cleft that causes regurgitation. Dr. del Nido explained his surgical approaches for mitral valve disease in children at the 2017 Mitral Conclave, sponsored by the American Association of Thoracic Surgery.

Accessing the mitral valve in children requires a different approach than in adults, Dr. del Nido said. “Going through the left atrium is generally difficult, so we often enter through a trans-septal incision,” he said. “The main reason for that is because the tricuspid valve is often associated with the mitral valve problem and this gives us the most direct exposure.”

Once the surgeon gains exposure, the surgical analysis for a diseased adult or child valve is almost identical, with the exception that adult disease is acquired whereas childhood disease tends to be congenital, Dr. del Nido said. “In the congenital patient, we often find fibroelastic tissue that the child is born with,” he said. “We see this in neonates and young infants. It thickens over time; it doesn’t often calcify, but it does often restrict the leaflets and it tends to fuse the chords, so in essence you have direct attachments of the leaflets to the papillaries.”

He explained that this pathology requires an approach similar to that for rheumatic mitral disease in adults. “Start splitting the commissures and start resecting the tissue off the chords creating fenestrations in order to improve the inflow.” Dr. del Nido added, “If you don’t do this, the child will always have a gradient, and if you think about an adult having problems and symptoms with a gradient, think about a 10-year-old running around trying to do athletics; it’s impossible.”

Dysfunctional chords also require a somewhat different approach in children than they require in adults. “We find elongation of the chords and the anterior support structure is abnormal; the secondary chords are totally intact,” Dr. del Nido said. When confronting a torn-edge chord, resection is often an option in adults, but is uncommon in children. “We don’t usually have very much leaflet tissue,” he said. Artificial chords do not accommodate growth.

“We tend to use native tissue,” said Dr. del Nido. “You can transfer the strut chord; you can transfer the secondary chord in order to achieve support for the edge of that prolapsed leaflet.”

Leaflet problems are probably the biggest single source of recurrence in children, Dr. del Nido said. A cleft on the anterior leaflet can be particularly vexing. For example, cleft edges attached to the septum can prevent the valve leaflet from coaptation with the posterior leaflet. “If you don’t recognize that on 3-D echocardiography, you’re going to have a problem; that leaflet will never create the coaptation surface that you want,” he said.

The solution may lie underneath the leaflet. Said Dr. del Nido, “We tend to want to close a cleft, and, yes, that will get you relief of regurgitation in the central portion, but if you end up with immobility of that leaflet, then look underneath. Most often there are very abnormal attachments to the edges of that cleft to the septum. You have to get rid of that; if you don’t resect all that, you’ll never have a leaflet that truly floats up to coapt against the posterior leaflet.”

Annular dilation in children can also challenge a cardiothoracic surgeon’s skill.

In rare cases, a suture commissuroplasty may correct the problem. Sometimes Dr. del Nido will use the DeVega suture annuloplasty – “even though it is very much user dependent; it’s very easy in pediatrics to create stenosis with the DeVega.” As an alternative, synthetic ring annuloplasties can confine valve growth and are rarely used.

Dr. del Nido’s preference is to use a hybrid approach of tissue and resorbable material. “The advantage of the resorbable material is that it will go away, but that’s also the problem with the resorbable material,” he said. “Once it does go away, there’s nothing there to support the annulus, so a combination of tissue and resorbable suture is probably the best answer.”

In posterior leaflet deficiency, a patch of pericardium posteriorly can augment the dysfunctional leaflet. You can also use pericardium as an annuloplasty ring. “You can use it circumferentially,” Dr. del Nido said. “It’s a soft ring; you can certainly use this material which is autologous; it does provide strength to the fibrous annulus; it does support that valve; and you do see growth.” He added that bovine pericardium is not ideal for this use.

Dr. del Nido reported no relevant financial relationships.

NEW YORK – Repairing mitral valves in pediatric patients must overcome two issues: the wide variability in their anatomy and their growth. Using strategies and techniques common in adult mitral surgery can accomplish good mitral valve function in children, but some techniques in children differ, like using combined resorbable material with autologous tissue or transferring native chords instead of placing artificial chords to a malfunctioning leaflet.

Pedro del Nido, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, said the spectrum of mitral valve pathology in children goes from congenital mitral stenosis with a thick annulus with leaflet immobility to leaflet hypermobility that involves anterior leaflet prolapse and can involve a cleft that causes regurgitation. Dr. del Nido explained his surgical approaches for mitral valve disease in children at the 2017 Mitral Conclave, sponsored by the American Association of Thoracic Surgery.

Accessing the mitral valve in children requires a different approach than in adults, Dr. del Nido said. “Going through the left atrium is generally difficult, so we often enter through a trans-septal incision,” he said. “The main reason for that is because the tricuspid valve is often associated with the mitral valve problem and this gives us the most direct exposure.”

Once the surgeon gains exposure, the surgical analysis for a diseased adult or child valve is almost identical, with the exception that adult disease is acquired whereas childhood disease tends to be congenital, Dr. del Nido said. “In the congenital patient, we often find fibroelastic tissue that the child is born with,” he said. “We see this in neonates and young infants. It thickens over time; it doesn’t often calcify, but it does often restrict the leaflets and it tends to fuse the chords, so in essence you have direct attachments of the leaflets to the papillaries.”

He explained that this pathology requires an approach similar to that for rheumatic mitral disease in adults. “Start splitting the commissures and start resecting the tissue off the chords creating fenestrations in order to improve the inflow.” Dr. del Nido added, “If you don’t do this, the child will always have a gradient, and if you think about an adult having problems and symptoms with a gradient, think about a 10-year-old running around trying to do athletics; it’s impossible.”

Dysfunctional chords also require a somewhat different approach in children than they require in adults. “We find elongation of the chords and the anterior support structure is abnormal; the secondary chords are totally intact,” Dr. del Nido said. When confronting a torn-edge chord, resection is often an option in adults, but is uncommon in children. “We don’t usually have very much leaflet tissue,” he said. Artificial chords do not accommodate growth.

“We tend to use native tissue,” said Dr. del Nido. “You can transfer the strut chord; you can transfer the secondary chord in order to achieve support for the edge of that prolapsed leaflet.”

Leaflet problems are probably the biggest single source of recurrence in children, Dr. del Nido said. A cleft on the anterior leaflet can be particularly vexing. For example, cleft edges attached to the septum can prevent the valve leaflet from coaptation with the posterior leaflet. “If you don’t recognize that on 3-D echocardiography, you’re going to have a problem; that leaflet will never create the coaptation surface that you want,” he said.

The solution may lie underneath the leaflet. Said Dr. del Nido, “We tend to want to close a cleft, and, yes, that will get you relief of regurgitation in the central portion, but if you end up with immobility of that leaflet, then look underneath. Most often there are very abnormal attachments to the edges of that cleft to the septum. You have to get rid of that; if you don’t resect all that, you’ll never have a leaflet that truly floats up to coapt against the posterior leaflet.”

Annular dilation in children can also challenge a cardiothoracic surgeon’s skill.

In rare cases, a suture commissuroplasty may correct the problem. Sometimes Dr. del Nido will use the DeVega suture annuloplasty – “even though it is very much user dependent; it’s very easy in pediatrics to create stenosis with the DeVega.” As an alternative, synthetic ring annuloplasties can confine valve growth and are rarely used.