User login

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

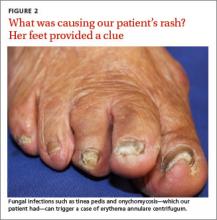

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.