User login

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

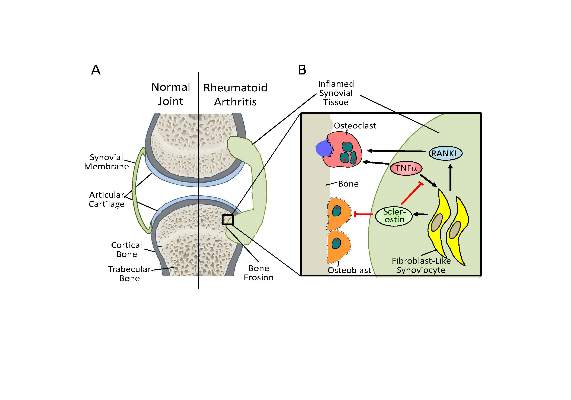

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE