User login

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Recently, my prescribing error caused a patient to get very sick. I feel terrible. I want to tell my patient I’m sorry, but I’ve heard that a lawyer could use my “confession” to prove I’ve committed malpractice. If I apologize, could my words come back to haunt me if a lawsuit is filed?

Submitted by “Dr. E”

As several faiths have long recognized, apologies are important social acts that express our awareness of and obligations to each other. In recent years, psychologists have established how apologies confer emotional benefits on those who give and receive them.1 Offering a sincere apology can be the right thing to do and a beneficial act for both the apologizing and the injured parties.

Traditionally, physicians have avoided apologizing for errors that harmed patients. Part of the reluctance stemmed from pride or wanting to avoid shame. But as Dr. E’s question suggests, doctors also have feared—and lawyers have advised—that apologizing might compromise a malpractice defense.2

Attitudes have changed in recent years, however. Increasingly, practitioners, medical organizations, and risk management entities are telling physicians they should apologize for errors, and many states have laws that mitigate adverse legal consequences of saying “I’m sorry.”

In response to Dr. E’s questions, I’ll examine:

• ethical and professional obligations following unexpected outcomes

• physicians’ reasons for being reluctant to apologize

• the benefits of apologizing

• legal protections for apologies.

Owning up: Ethical and professional expectations

Current codes of medical ethics say that physicians should tell patients when mistakes and misjudgments have caused harm. “It is a fundamental ethical requirement that a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients,” states the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics. When a patient suffers because of a medical error, “the physician is ethically required to inform the patient of all the facts necessary to ensure” the patient can “make informed decisions regarding future medical care.”3

The National Patient Safety Foundation,4 the American College of Physicians,5 and the Joint Commission (the agency that provides official accreditation of thousands of healthcare organizations) have voiced similar positions for years. Since 2001, the Joint Commission has required that practitioners and medical facilities tell patients and families “about the outcomes of care, treatment, and services ... including unanticipated outcomes.”6

Reluctance is understandable

Although these recommendations and policies suggest that telling patients about medical errors is an established professional expectation, physicians remain reluctant to apologize to patients for emotional and legal reasons that are easy to understand.

Apologizing is hard. On one hand, research shows that refusing to apologize sometimes increases feelings of empowerment and control, and can boost self-esteem more than apologizing does.7 On the other, apologizing often requires one to acknowledge a failure or betrayal of trust and to experience guilt, shame, embarrassment, or fear that one’s apology will be met with anger or rejection.8

Physicians historically have treated errors as personal failures. Apologizing in a medical context can feel like saying, “I am incompetent.”9,10 The law has reinforced this attitude. As the Mississippi Supreme Court put it, “Medical malpractice is legal fault by a physician or surgeon. It arises from the failure of a physician to provide the quality of care required by law” (emphasis added).11

Some lawyers continue to advise physicians not to make admissions that could be used in a malpractice case. Their reasoning: If a doctor does something that adversely affects a malpractice insurer’s ability to defend the case, the insurer might not provide liability coverage for the adverse event.12

Emotional and legal benefits

Against this no-apology stance is a growing body of theoretical, empirical, and practical arguments favoring apologies for medical errors. Case studies suggest that anger is behind much medical malpractice litigation and that physicians’ apologies—which reduce anger and increase communication—might reduce patients’ motivations to sue.13 Apologies sometimes lead to forgiveness, an emotional state that “can provide victims and offenders with many important benefits, including enhanced psychological well-being ... and greater physiological health.”14 Apologies do this by mitigating the injured party’s negative emotional states and diminishing rumination about the transgression and perceived harm severity.

The practical argument favoring apologizing is that it may defuse feelings that lead to lawsuits and reduce the size of payouts. Experimental studies suggest that apologizing leads to earlier satisfaction and closure, faster settlements, and lower damage payments. When apologies include admissions of fault, injured parties feel greater respect for and less need to punish those who have harmed them, are more willing to forgive, and are more likely to accept settlement offers.15

Hospitals in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Michigan have found that sincere apologies and effective error disclosure programs reduce malpractice payouts and lead to faster settlements.16 As some plaintiffs’ lawyers point out, being honest and forthright and fixing the injured parties’ problems can quickly defuse a lawsuit. One attorney explained things this way: “We never sue the nice, contrite doctors. Their patients never call our offices. But the doctors who are poor communicators and abandon their patients get sued all the time. Their patients come to our offices looking for answers.”17

Apology laws: Protection from your own words

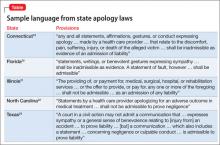

The belief that apologies by physicians can help patients emotionally and reduce malpractice litigation has led state legislatures to enact so-called apology laws in many jurisdictions in the United States.18 The general point of these rules and statutes is to prevent later use of doctors’ words in litigation. States differ substantially in the scope and type of protection that their laws offer. Some states prohibit doctors’ apologies for adverse outcomes from being used in litigation to prove negligence, while others only exclude expressions of sympathy or offers to pay for corrective treatment. Selected language from several states’ apology laws appears in the Table.19-23

Do apology laws work? Recent research by economists Ho and Liu indicates that they do. Comparing payouts in states with and without apology laws, they conclude that “apology laws have the greatest reduction in average payment size and settlement time in cases involving more severe patient outcomes,”13 such as obstetrics and anesthesia cases, cases that involve infants, and cases in which physicians improperly manage or fail to properly diagnose an illness.24

The practical impact of apologizing for psychiatric malpractice cases is unclear, but forensic psychiatrists Marilyn Price and Patricia Recupero believe that, following some unexpected outcomes, thoughtful expressions of sympathy, regret, and—if the outcome resulted from an error—apologies may be appropriate. Price and Recupero caution that such conversations should occur as part of broader programs that investigate unanticipated adverse events and provide education and coaching about appropriate ways to make disclosures. Clinicians also should consult with legal counsel, risk management officers, and liability insurance carriers before initiating such disclosures.25

Bottom Line

Apologizing for medical errors may mitigate malpractice liability and can help injured parties and physicians feel better. Whether plaintiffs can use apologies as evidence of malpractice depends on state laws and rules of evidence. Before you apologize for an unanticipated outcome, discuss the situation with your legal counsel, risk management officers, and insurers.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Douglas Mossman, MD, talks about who you should consult before apologizing to a patient for a bad outcome. Dr. Mossman is Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Director, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

1. McCullough ME, Sandage SJ, Brown SW, et al. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1586-1603.

2. O’Reilly KB. “I’m sorry”: why is that so hard for doctors to say? http://www.amednews.com/article/20100201/profession/302019937/4. Published February 1, 2010. Accessed September 30, 2013.

3. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, Opinion 8.12 – Patient information. http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion812.page. Published June 1994. Accessed September 30, 2013.

4. Hickson GB, Pichert JW. Disclosure and apology. http://www.npsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/RG_SUPS_After_Mod1_Hickson.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2013.

5. Snyder L, American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians ethics manual: sixth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(1, pt 2):73-104.

6. ECRI Institute. Disclosure of unanticipated outcomes. In: Healthcare risk control Supplement A, Risk analysis. Plymouth Meeting, PA: ECRI; 2002.

7. Okimoto TG, Wenzel M, Hedrick K. Refusing to apologize can have psychological benefits (and we issue no mea culpa for this research finding). Eur J Soc Psychol. 2013;43:22-31.

8. Lazare A. On apology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

9. Hilfiker D. Facing our mistakes. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:

118-122.

10. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851-1857.

11. Hall v. Hilbun, 466 So.2d 856 (Miss. 1985).

12. Kern SI. You continue to face exposure if you apologize. http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-now/you-continue-face-exposure-if-you-apologiz. Published September 24, 2010. Accessed October 1, 2013.

13. Ho B, Liu E. Does sorry work? The impact of apology laws on medical malpractice. J Risk Uncertain. 2011;43(2):141-167.

14. Fehr R, Gelfand MJ, Nag M. The road to forgiveness: a meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:894-914.

15. Robbennolt JK. Apologies and settlement. Court Review. 2009;45:90-97.

16. Saitta N, Hodge SD. Efficacy of a physician’s words of empathy: an overview of state apology laws. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112(5):302-306.

17. Wojcieszak D, Banja J, Houk C. The sorry works! coalition: making the case for full disclosure. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(6):344-350.

18. National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical liability/Medical malpractice laws. http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/banking/medical-liability-medical-malpractice-laws.aspx. Published August 15, 2011. Accessed October 4, 2013.

19. Conn Gen Stat Ann §52-184d(b).

20. Fla Stat §90.4026(2).

21. Ill Comp Stat §5/8-1901.

22. NC Gen Stat §8C-1, Rule 413.

23. Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §18.061.

24. Ho B, Liu E. What’s an apology worth? Decomposing the effect of apologies on medical malpractice payments using state apology laws. J Empir Leg Stud. 2011;8:179-199.

25. Price M, Recupero PR. Risk management. In: Sharfstein SS, Dickerson FB, Oldham JM, eds. Textbook of hospital psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:411-412.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Recently, my prescribing error caused a patient to get very sick. I feel terrible. I want to tell my patient I’m sorry, but I’ve heard that a lawyer could use my “confession” to prove I’ve committed malpractice. If I apologize, could my words come back to haunt me if a lawsuit is filed?

Submitted by “Dr. E”

As several faiths have long recognized, apologies are important social acts that express our awareness of and obligations to each other. In recent years, psychologists have established how apologies confer emotional benefits on those who give and receive them.1 Offering a sincere apology can be the right thing to do and a beneficial act for both the apologizing and the injured parties.

Traditionally, physicians have avoided apologizing for errors that harmed patients. Part of the reluctance stemmed from pride or wanting to avoid shame. But as Dr. E’s question suggests, doctors also have feared—and lawyers have advised—that apologizing might compromise a malpractice defense.2

Attitudes have changed in recent years, however. Increasingly, practitioners, medical organizations, and risk management entities are telling physicians they should apologize for errors, and many states have laws that mitigate adverse legal consequences of saying “I’m sorry.”

In response to Dr. E’s questions, I’ll examine:

• ethical and professional obligations following unexpected outcomes

• physicians’ reasons for being reluctant to apologize

• the benefits of apologizing

• legal protections for apologies.

Owning up: Ethical and professional expectations

Current codes of medical ethics say that physicians should tell patients when mistakes and misjudgments have caused harm. “It is a fundamental ethical requirement that a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients,” states the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics. When a patient suffers because of a medical error, “the physician is ethically required to inform the patient of all the facts necessary to ensure” the patient can “make informed decisions regarding future medical care.”3

The National Patient Safety Foundation,4 the American College of Physicians,5 and the Joint Commission (the agency that provides official accreditation of thousands of healthcare organizations) have voiced similar positions for years. Since 2001, the Joint Commission has required that practitioners and medical facilities tell patients and families “about the outcomes of care, treatment, and services ... including unanticipated outcomes.”6

Reluctance is understandable

Although these recommendations and policies suggest that telling patients about medical errors is an established professional expectation, physicians remain reluctant to apologize to patients for emotional and legal reasons that are easy to understand.

Apologizing is hard. On one hand, research shows that refusing to apologize sometimes increases feelings of empowerment and control, and can boost self-esteem more than apologizing does.7 On the other, apologizing often requires one to acknowledge a failure or betrayal of trust and to experience guilt, shame, embarrassment, or fear that one’s apology will be met with anger or rejection.8

Physicians historically have treated errors as personal failures. Apologizing in a medical context can feel like saying, “I am incompetent.”9,10 The law has reinforced this attitude. As the Mississippi Supreme Court put it, “Medical malpractice is legal fault by a physician or surgeon. It arises from the failure of a physician to provide the quality of care required by law” (emphasis added).11

Some lawyers continue to advise physicians not to make admissions that could be used in a malpractice case. Their reasoning: If a doctor does something that adversely affects a malpractice insurer’s ability to defend the case, the insurer might not provide liability coverage for the adverse event.12

Emotional and legal benefits

Against this no-apology stance is a growing body of theoretical, empirical, and practical arguments favoring apologies for medical errors. Case studies suggest that anger is behind much medical malpractice litigation and that physicians’ apologies—which reduce anger and increase communication—might reduce patients’ motivations to sue.13 Apologies sometimes lead to forgiveness, an emotional state that “can provide victims and offenders with many important benefits, including enhanced psychological well-being ... and greater physiological health.”14 Apologies do this by mitigating the injured party’s negative emotional states and diminishing rumination about the transgression and perceived harm severity.

The practical argument favoring apologizing is that it may defuse feelings that lead to lawsuits and reduce the size of payouts. Experimental studies suggest that apologizing leads to earlier satisfaction and closure, faster settlements, and lower damage payments. When apologies include admissions of fault, injured parties feel greater respect for and less need to punish those who have harmed them, are more willing to forgive, and are more likely to accept settlement offers.15

Hospitals in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Michigan have found that sincere apologies and effective error disclosure programs reduce malpractice payouts and lead to faster settlements.16 As some plaintiffs’ lawyers point out, being honest and forthright and fixing the injured parties’ problems can quickly defuse a lawsuit. One attorney explained things this way: “We never sue the nice, contrite doctors. Their patients never call our offices. But the doctors who are poor communicators and abandon their patients get sued all the time. Their patients come to our offices looking for answers.”17

Apology laws: Protection from your own words

The belief that apologies by physicians can help patients emotionally and reduce malpractice litigation has led state legislatures to enact so-called apology laws in many jurisdictions in the United States.18 The general point of these rules and statutes is to prevent later use of doctors’ words in litigation. States differ substantially in the scope and type of protection that their laws offer. Some states prohibit doctors’ apologies for adverse outcomes from being used in litigation to prove negligence, while others only exclude expressions of sympathy or offers to pay for corrective treatment. Selected language from several states’ apology laws appears in the Table.19-23

Do apology laws work? Recent research by economists Ho and Liu indicates that they do. Comparing payouts in states with and without apology laws, they conclude that “apology laws have the greatest reduction in average payment size and settlement time in cases involving more severe patient outcomes,”13 such as obstetrics and anesthesia cases, cases that involve infants, and cases in which physicians improperly manage or fail to properly diagnose an illness.24

The practical impact of apologizing for psychiatric malpractice cases is unclear, but forensic psychiatrists Marilyn Price and Patricia Recupero believe that, following some unexpected outcomes, thoughtful expressions of sympathy, regret, and—if the outcome resulted from an error—apologies may be appropriate. Price and Recupero caution that such conversations should occur as part of broader programs that investigate unanticipated adverse events and provide education and coaching about appropriate ways to make disclosures. Clinicians also should consult with legal counsel, risk management officers, and liability insurance carriers before initiating such disclosures.25

Bottom Line

Apologizing for medical errors may mitigate malpractice liability and can help injured parties and physicians feel better. Whether plaintiffs can use apologies as evidence of malpractice depends on state laws and rules of evidence. Before you apologize for an unanticipated outcome, discuss the situation with your legal counsel, risk management officers, and insurers.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Douglas Mossman, MD, talks about who you should consult before apologizing to a patient for a bad outcome. Dr. Mossman is Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Director, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

Recently, my prescribing error caused a patient to get very sick. I feel terrible. I want to tell my patient I’m sorry, but I’ve heard that a lawyer could use my “confession” to prove I’ve committed malpractice. If I apologize, could my words come back to haunt me if a lawsuit is filed?

Submitted by “Dr. E”

As several faiths have long recognized, apologies are important social acts that express our awareness of and obligations to each other. In recent years, psychologists have established how apologies confer emotional benefits on those who give and receive them.1 Offering a sincere apology can be the right thing to do and a beneficial act for both the apologizing and the injured parties.

Traditionally, physicians have avoided apologizing for errors that harmed patients. Part of the reluctance stemmed from pride or wanting to avoid shame. But as Dr. E’s question suggests, doctors also have feared—and lawyers have advised—that apologizing might compromise a malpractice defense.2

Attitudes have changed in recent years, however. Increasingly, practitioners, medical organizations, and risk management entities are telling physicians they should apologize for errors, and many states have laws that mitigate adverse legal consequences of saying “I’m sorry.”

In response to Dr. E’s questions, I’ll examine:

• ethical and professional obligations following unexpected outcomes

• physicians’ reasons for being reluctant to apologize

• the benefits of apologizing

• legal protections for apologies.

Owning up: Ethical and professional expectations

Current codes of medical ethics say that physicians should tell patients when mistakes and misjudgments have caused harm. “It is a fundamental ethical requirement that a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients,” states the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics. When a patient suffers because of a medical error, “the physician is ethically required to inform the patient of all the facts necessary to ensure” the patient can “make informed decisions regarding future medical care.”3

The National Patient Safety Foundation,4 the American College of Physicians,5 and the Joint Commission (the agency that provides official accreditation of thousands of healthcare organizations) have voiced similar positions for years. Since 2001, the Joint Commission has required that practitioners and medical facilities tell patients and families “about the outcomes of care, treatment, and services ... including unanticipated outcomes.”6

Reluctance is understandable

Although these recommendations and policies suggest that telling patients about medical errors is an established professional expectation, physicians remain reluctant to apologize to patients for emotional and legal reasons that are easy to understand.

Apologizing is hard. On one hand, research shows that refusing to apologize sometimes increases feelings of empowerment and control, and can boost self-esteem more than apologizing does.7 On the other, apologizing often requires one to acknowledge a failure or betrayal of trust and to experience guilt, shame, embarrassment, or fear that one’s apology will be met with anger or rejection.8

Physicians historically have treated errors as personal failures. Apologizing in a medical context can feel like saying, “I am incompetent.”9,10 The law has reinforced this attitude. As the Mississippi Supreme Court put it, “Medical malpractice is legal fault by a physician or surgeon. It arises from the failure of a physician to provide the quality of care required by law” (emphasis added).11

Some lawyers continue to advise physicians not to make admissions that could be used in a malpractice case. Their reasoning: If a doctor does something that adversely affects a malpractice insurer’s ability to defend the case, the insurer might not provide liability coverage for the adverse event.12

Emotional and legal benefits

Against this no-apology stance is a growing body of theoretical, empirical, and practical arguments favoring apologies for medical errors. Case studies suggest that anger is behind much medical malpractice litigation and that physicians’ apologies—which reduce anger and increase communication—might reduce patients’ motivations to sue.13 Apologies sometimes lead to forgiveness, an emotional state that “can provide victims and offenders with many important benefits, including enhanced psychological well-being ... and greater physiological health.”14 Apologies do this by mitigating the injured party’s negative emotional states and diminishing rumination about the transgression and perceived harm severity.

The practical argument favoring apologizing is that it may defuse feelings that lead to lawsuits and reduce the size of payouts. Experimental studies suggest that apologizing leads to earlier satisfaction and closure, faster settlements, and lower damage payments. When apologies include admissions of fault, injured parties feel greater respect for and less need to punish those who have harmed them, are more willing to forgive, and are more likely to accept settlement offers.15

Hospitals in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Michigan have found that sincere apologies and effective error disclosure programs reduce malpractice payouts and lead to faster settlements.16 As some plaintiffs’ lawyers point out, being honest and forthright and fixing the injured parties’ problems can quickly defuse a lawsuit. One attorney explained things this way: “We never sue the nice, contrite doctors. Their patients never call our offices. But the doctors who are poor communicators and abandon their patients get sued all the time. Their patients come to our offices looking for answers.”17

Apology laws: Protection from your own words

The belief that apologies by physicians can help patients emotionally and reduce malpractice litigation has led state legislatures to enact so-called apology laws in many jurisdictions in the United States.18 The general point of these rules and statutes is to prevent later use of doctors’ words in litigation. States differ substantially in the scope and type of protection that their laws offer. Some states prohibit doctors’ apologies for adverse outcomes from being used in litigation to prove negligence, while others only exclude expressions of sympathy or offers to pay for corrective treatment. Selected language from several states’ apology laws appears in the Table.19-23

Do apology laws work? Recent research by economists Ho and Liu indicates that they do. Comparing payouts in states with and without apology laws, they conclude that “apology laws have the greatest reduction in average payment size and settlement time in cases involving more severe patient outcomes,”13 such as obstetrics and anesthesia cases, cases that involve infants, and cases in which physicians improperly manage or fail to properly diagnose an illness.24

The practical impact of apologizing for psychiatric malpractice cases is unclear, but forensic psychiatrists Marilyn Price and Patricia Recupero believe that, following some unexpected outcomes, thoughtful expressions of sympathy, regret, and—if the outcome resulted from an error—apologies may be appropriate. Price and Recupero caution that such conversations should occur as part of broader programs that investigate unanticipated adverse events and provide education and coaching about appropriate ways to make disclosures. Clinicians also should consult with legal counsel, risk management officers, and liability insurance carriers before initiating such disclosures.25

Bottom Line

Apologizing for medical errors may mitigate malpractice liability and can help injured parties and physicians feel better. Whether plaintiffs can use apologies as evidence of malpractice depends on state laws and rules of evidence. Before you apologize for an unanticipated outcome, discuss the situation with your legal counsel, risk management officers, and insurers.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Douglas Mossman, MD, talks about who you should consult before apologizing to a patient for a bad outcome. Dr. Mossman is Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Director, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

1. McCullough ME, Sandage SJ, Brown SW, et al. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1586-1603.

2. O’Reilly KB. “I’m sorry”: why is that so hard for doctors to say? http://www.amednews.com/article/20100201/profession/302019937/4. Published February 1, 2010. Accessed September 30, 2013.

3. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, Opinion 8.12 – Patient information. http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion812.page. Published June 1994. Accessed September 30, 2013.

4. Hickson GB, Pichert JW. Disclosure and apology. http://www.npsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/RG_SUPS_After_Mod1_Hickson.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2013.

5. Snyder L, American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians ethics manual: sixth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(1, pt 2):73-104.

6. ECRI Institute. Disclosure of unanticipated outcomes. In: Healthcare risk control Supplement A, Risk analysis. Plymouth Meeting, PA: ECRI; 2002.

7. Okimoto TG, Wenzel M, Hedrick K. Refusing to apologize can have psychological benefits (and we issue no mea culpa for this research finding). Eur J Soc Psychol. 2013;43:22-31.

8. Lazare A. On apology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

9. Hilfiker D. Facing our mistakes. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:

118-122.

10. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851-1857.

11. Hall v. Hilbun, 466 So.2d 856 (Miss. 1985).

12. Kern SI. You continue to face exposure if you apologize. http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-now/you-continue-face-exposure-if-you-apologiz. Published September 24, 2010. Accessed October 1, 2013.

13. Ho B, Liu E. Does sorry work? The impact of apology laws on medical malpractice. J Risk Uncertain. 2011;43(2):141-167.

14. Fehr R, Gelfand MJ, Nag M. The road to forgiveness: a meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:894-914.

15. Robbennolt JK. Apologies and settlement. Court Review. 2009;45:90-97.

16. Saitta N, Hodge SD. Efficacy of a physician’s words of empathy: an overview of state apology laws. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112(5):302-306.

17. Wojcieszak D, Banja J, Houk C. The sorry works! coalition: making the case for full disclosure. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(6):344-350.

18. National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical liability/Medical malpractice laws. http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/banking/medical-liability-medical-malpractice-laws.aspx. Published August 15, 2011. Accessed October 4, 2013.

19. Conn Gen Stat Ann §52-184d(b).

20. Fla Stat §90.4026(2).

21. Ill Comp Stat §5/8-1901.

22. NC Gen Stat §8C-1, Rule 413.

23. Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §18.061.

24. Ho B, Liu E. What’s an apology worth? Decomposing the effect of apologies on medical malpractice payments using state apology laws. J Empir Leg Stud. 2011;8:179-199.

25. Price M, Recupero PR. Risk management. In: Sharfstein SS, Dickerson FB, Oldham JM, eds. Textbook of hospital psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:411-412.

1. McCullough ME, Sandage SJ, Brown SW, et al. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:1586-1603.

2. O’Reilly KB. “I’m sorry”: why is that so hard for doctors to say? http://www.amednews.com/article/20100201/profession/302019937/4. Published February 1, 2010. Accessed September 30, 2013.

3. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics, Opinion 8.12 – Patient information. http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion812.page. Published June 1994. Accessed September 30, 2013.

4. Hickson GB, Pichert JW. Disclosure and apology. http://www.npsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/RG_SUPS_After_Mod1_Hickson.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2013.

5. Snyder L, American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee. American College of Physicians ethics manual: sixth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(1, pt 2):73-104.

6. ECRI Institute. Disclosure of unanticipated outcomes. In: Healthcare risk control Supplement A, Risk analysis. Plymouth Meeting, PA: ECRI; 2002.

7. Okimoto TG, Wenzel M, Hedrick K. Refusing to apologize can have psychological benefits (and we issue no mea culpa for this research finding). Eur J Soc Psychol. 2013;43:22-31.

8. Lazare A. On apology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

9. Hilfiker D. Facing our mistakes. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:

118-122.

10. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851-1857.

11. Hall v. Hilbun, 466 So.2d 856 (Miss. 1985).

12. Kern SI. You continue to face exposure if you apologize. http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-now/you-continue-face-exposure-if-you-apologiz. Published September 24, 2010. Accessed October 1, 2013.

13. Ho B, Liu E. Does sorry work? The impact of apology laws on medical malpractice. J Risk Uncertain. 2011;43(2):141-167.

14. Fehr R, Gelfand MJ, Nag M. The road to forgiveness: a meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:894-914.

15. Robbennolt JK. Apologies and settlement. Court Review. 2009;45:90-97.

16. Saitta N, Hodge SD. Efficacy of a physician’s words of empathy: an overview of state apology laws. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112(5):302-306.

17. Wojcieszak D, Banja J, Houk C. The sorry works! coalition: making the case for full disclosure. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(6):344-350.

18. National Conference of State Legislatures. Medical liability/Medical malpractice laws. http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/banking/medical-liability-medical-malpractice-laws.aspx. Published August 15, 2011. Accessed October 4, 2013.

19. Conn Gen Stat Ann §52-184d(b).

20. Fla Stat §90.4026(2).

21. Ill Comp Stat §5/8-1901.

22. NC Gen Stat §8C-1, Rule 413.

23. Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code §18.061.

24. Ho B, Liu E. What’s an apology worth? Decomposing the effect of apologies on medical malpractice payments using state apology laws. J Empir Leg Stud. 2011;8:179-199.

25. Price M, Recupero PR. Risk management. In: Sharfstein SS, Dickerson FB, Oldham JM, eds. Textbook of hospital psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:411-412.