User login

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

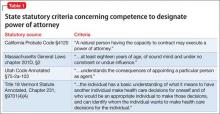

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

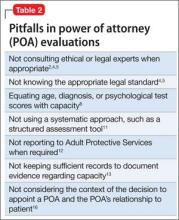

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

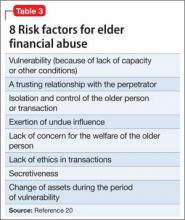

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.