User login

Considering work as an expert witness? Look before you leap!

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

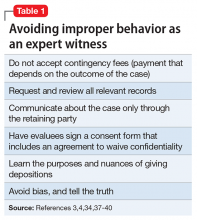

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

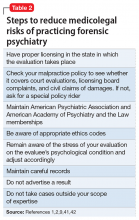

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

I am retired, but an attorney friend of mine has asked me to help out by performing forensic evaluations. I’m tempted to try it because the work sounds meaningful and interesting. I won’t have a doctor–patient relationship with the attorney’s clients, and I expect the work will take <10 hours a week. Do I need malpractice coverage? Should I consider any other medicolegal issues before I start?

Submitted by “Dr. B”

One of the great things about being a psychiatrist is the variety of available practice options. Like Dr. B, many psychiatrists contemplate using their clinical know-how to perform forensic evaluations. For some psychiatrists, part-time work as an expert witness may provide an appealing change of pace from their other clinical duties1 and a way to supplement their income.2

But as would be true for other kinds of medical practice, Dr. B is wise to consider the possible risks before jumping into forensic work. To help Dr. B decide about getting insurance coverage, we will:

- explain briefly the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry

- review the theory of malpractice and negligence torts

- discuss whether forensic evaluations can create doctor–patient relationships

- explore the availability and limitations of immunity for forensic work

- describe other types of liability with forensic work

- summarize steps to avoid liability.

Introduction to forensic psychiatry

Some psychiatrists—and many people who are not psychiatrists—have a vague or incorrect understanding of forensic psychiatry. Put succinctly, “Forensic Psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts….”3 To practice forensic psychiatry well, a psychiatrist must have some understanding of the law and how to apply and translate clinical concepts to fit legal criteria.4 Psychiatrists who offer to serve as expert witnesses should be familiar with how the courtroom functions, the nuances of how expert testimony is used, and possible sources of bias.4,5

Forensic work can create role conflicts. For most types of forensic assessments, psychiatrists should not provide forensic opinions or testimony about their own patients.3 Even psychiatrists who only work as expert witnesses must balance duties of assisting the trier of fact, fulfilling the consultation role to the retaining party, upholding the standards and ethics of the profession, and striving to provide truthful, objective testimony.2

Special training usually is required

The most important qualification for being a good psychiatric expert witness is being a good psychiatrist, and courts do not require psychiatrists to have specialty training in forensic psychiatry to perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Yet, the field of forensic psychiatry has developed over the past 50 years to the point that psychiatrists need special training to properly perform many, if not most, types of forensic evaluations.6 Much of forensic psychiatry involves writing specialized reports for lawyers and the court,7 and experts are supposed to meet professional standards, regardless of their training.8-10 Psychiatrists who perform forensic work are obligated to claim expertise only in areas where their knowledge, skills, training, and experience justify such claims. These considerations explain why, since 1999, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology has limited eligibility for board certification in forensic psychiatry to psychiatrists who have completed accredited forensic fellowships.11

Malpractice: A short review

To address Dr. B’s question about malpractice coverage, we first review what malpractice is.

“Tort” is a legal term for injury, and tort claims arise when one party harms another and the harmed party seeks money as compensation.9 In a tort claim alleging negligence, the plaintiff (ie, the person bringing the suit) asserts that the defendant had a legally recognized duty, that the defendant breached that duty, and that breach of duty harmed the plaintiff.8

Physicians have a legal duty to “possess the requisite knowledge and skill such as is possessed by the average member of the medical profession; … exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the application of such knowledge and skill; and … use best judgment in such application.”10 A medical malpractice lawsuit asserts that a doctor breached this duty and caused injury in the course of the medical practice.

Malpractice in forensic cases

Practicing medicine typically occurs within the context of treatment relationships. One might think, as Dr. B did, that because forensic evaluations do not involve treating patients, they do not create the kind of doctor–patient relationship that could lead to malpractice liability. This is incorrect, however, for several reasons.

Certain well-intended actions during a forensic evaluation, such as explaining the implications of a diagnosis, giving specific advice about a medication, or making a recommendation about where or how to obtain treatment, may create a doctor–patient relationship.12,13 Many states’ laws on what constitutes the practice of medicine include performing examinations, diagnosing, or referring to oneself as “Dr.” or as a medical practitioner.14-17 State courts have interpreted these laws to further define what constitutes medical practice and the creation of a doctor–patient relationship during a forensic examination.18,19 Some legal scholars20 and the American Medical Association (AMA)9 regard provision of expert testimony as practicing medicine because such testimony requires the application of medical science and rendering of diagnoses.

Immunity and shifts away from it

For many years, courts granted civil immunity to expert witnesses for several policy reasons.8,9,13,20-22 Courts recognized that losing parties might want to blame whomever they could, and immunity could provide legal protection for expert witnesses. Without such protection, witnesses might feel more pressured to give testimony favorable to their side at the loss of objectivity,23,24 or experts might be discouraged from testifying at all. This would be true especially for academic psychiatrists who testify infrequently or for retired doctors, such as Dr. B, who might not want to carry insurance for just one case.21 According to this argument, rather than using the threat of litigation to keep out improper testimony, courts should rely on both admissibility standards25,26 and the adversarial nature of proceedings.21

Those who oppose granting immunity to experts argue that admissibility rules and cross-examination do too little to prevent bad testimony; the threat of liability, however, motivates experts to be more cautious and scientifically rigorous in their approach.21 Opponents also have argued that the threat of liability might reduce improper testimony, which they believe was partly responsible for rising malpractice premiums.20

Courts vary in how they consider granting immunity and to what extent. For example:

- Some courts will not grant immunity to so-called “friendly experts,” while others have limited immunity for adversarial experts.20-22

- Some courts have applied immunity to general fact witnesses but not to professional experts.21,24,27

- When immunity is considered, it is usually regarding actual testimony. Yet, some courts have included pretrial services.21,28-30

- Some courts have considered the testimonial issue at hand when deciding whether to extend immunity. For example, immunity may not apply if the issue is loss of profits21,31 or if an experiment is conducted to demonstrate the extent of a physical injury.21,32

If you plan to serve as an expert witness, find out what, if any, immunity is available in the jurisdiction where you expect to testify. If you do not have immunity, you may be subject to various malpractice claims, including alleged physical or emotional harm resulting from the evaluation1 (perhaps caused by misuse of empathic statements33), an accusation of negligent misdiagnosis of an evaluee,8 or failing to act upon a duty to warn or protect that arises during an assessment.34

Other liability

Dr. B also asked about medicolegal issues other than malpractice. Although negligence is the claim that forensic psychiatrists most commonly encounter,10 other types of claims arise in practice-related legal actions. Potential causes of action include failure to obtain or attempt to obtain informed consent, breach of confidentiality, or not responding to a psychiatric emergency during evaluation. The plaintiff usually must show that the expert’s conduct was the cause-in-fact of injury.8

Besides civil lawsuits, forensic work may generate complaints to state medical boards.10 Occasionally, state medical boards have revoked psychiatrists’ licenses for improper testimony.20 Aggrieved parties may allege violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, such as mishandling protected health information. Psychiatrists also may face sanction by professional societies—for example, censure by the American Psychiatric Association9,10 or the AMA13 for ethics violations—if their improper testimony is considered unprofessional conduct. The theory behind this is that judges and jurors cannot be technical experts in every field, so the field must have a mechanism to police itself.20,35,36 Finally, forensic experts can face criminal charges for perjury if they lie under oath.8

How to protect yourself

Even when legal claims against psychiatrists turn out to be baseless, legal costs of defending oneself can mount quickly. Knowing this, Dr. B may conclude that obtaining malpractice insurance would be wise. But a malpractice policy alone may not meet all Dr. B’s needs, because some policies do not cover ordinary negligence or other potential causes of legal action against a psychiatrist.13 Some companies offer these extra types of coverage for work as an expert witness at no additional cost, and some offer access to risk management services with specialized knowledge about forensic psychiatric practice.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

1. Appelbaum PS. Law and psychiatry: liability for forensic evaluations: a word of caution. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):885-886.

2. Shuman DW, Greenberg SA. The expert witness, the adversary system, and the voice of reason: reconciling impartiality and advocacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34(3):219-224.

3. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Ethics guidelines for the practice of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/ethics.htm. Published May 2005. Accessed July 11, 2017.

4. Gutheil TG. Forensic psychiatry as a specialty. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/forensic-psychiatry-sp

5. Knoll J, Gerbasi J. Psychiatric malpractice case analysis: striving for objectivity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(2):215-223.

6. Sadoff RL. The practice of forensic psychiatry: perils, problems, and pitfalls. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1998;26(2):305-314.

7. Simon RI. Authorship in forensic psychiatry: a perspective. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):18-26.

8. Masterson LR. Witness immunity or malpractice liability for professionals hired as experts? Rev Litig. 1998;17(2):393-418.

9. Binder RL. Liability for the psychiatrist expert witness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1819-1825.

10. Gold LH, Davidson JE. Do you understand your risk? Liability and third-party evaluations in civil litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(2):200-210.

11. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. ABPN certification in the subspecialty of forensic psychiatry. http://www.aapl.org/abpn-certification. Accessed July 9, 2017.

12. Marett CP, Mossman D. What are your responsibilities after a screening call? Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(9):54-57.

13. Weinstock R, Garrick T. Is liability possible for forensic psychiatrists? Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23(2):183-193.

14. Ohio Revised Code §4731.34.

15. Kentucky Revised Statutes §311.550(10) (2017).

16. California Business & Professions Code §2052.5 (through 2012 Leg Sess).

17. Oregon Revised Statutes §677.085 (2013).

18. Blake V. When is a patient-physician relationship established? Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):403-406.

19. Zettler PJ. Toward coherent federal oversight of medicine. San Diego Law Review. 2015;52:427-500.

20. Turner JA. Going after the ‘hired guns’: is improper expert witness testimony unprofessional conduct or the negligent practice of medicine? Spec Law Dig Health Care Law. 2006;328:9-43.

21. Weiss LS, Orrick H. Expert witness malpractice actions: emerging trend or aberration? Practical Litigator. 2004;15(2):27-38.

22. McAbee GN. Improper expert medical testimony. Existing and proposed mechanisms of oversight. J Leg Med. 1998;19(2):257-272.

23. Panitz v Behrend, 632 A 2d 562 (Pa Super Ct 1993).

24. Murphy v A.A. Mathews, 841 S.W. 2d 671 (Mo 1992).

25. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

26. Rule 702. Testimony by expert witnesses. In: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd. Federal Rules of evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Legal Publishing Ltd; 2017:21.

27. Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management. Policy statement—expert witness participation in civil and criminal proceedings. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):428-438.

28. Mattco Forge, Inc., v Arthur Young & Co., 6 Cal Rptr 2d 781 (Cal Ct App 1992).

29. Marrogi v Howard, 248 F 3d 382 (5th Cir 2001).

30. Boyes-Bogie v Horvitz, 2001 WL 1771989 (Mass Super 2001).

31. LLMD of Michigan, Inc., v Jackson-Cross Co., 740 A. 2d 186 (Pa 1999).

32. Pollock v Panjabi, 781 A 2d 518 (Conn Super Ct 2000).

33. Brodsky SL, Wilson JK. Empathy in forensic evaluations: a systematic reconsideration. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):192-202.

34. Heilbrun K, DeMatteo D, Marczyk G, et al. Standards of practice and care in forensic mental health assessment: legal, professional, and principles-based consideration. Psych Pub Pol L. 2008;14(1):1-26.

35. Appelbaum PS. Law & psychiatry: policing expert testimony: the role of professional organizations. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(4):389-390,399.

36. Austin v American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 253 F 3d 967 (7th Cir 2001).

37. Gutheil TG, Simon RI. Attorneys’ pressures on the expert witness: early warning signs of endangered honesty, objectivity, and fair compensation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1999;27(4):546-553; discussion 554-562.

38. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(suppl 4):S3-S50.

39. Knoll JL IV, Resnick PJ. Deposition dos and don’ts: how to answer 8 tricky questions. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):25-28,36,39-40.

40. Hoge MA, Tebes JK, Davidson L, et al. The roles of behavioral health professionals in class action litigation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(1):49-58; discussion 59-64.

41. Simon RI, Shuman DW. Conducting forensic examinations on the road: are you practicing your profession without a license? Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2001;29(1):75-82.

42. Reid WH. Licensure requirements for out-of-state forensic examinations. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(4):433-437.

43. Collins B, ed. When in doubt, tell the truth: and other quotations from Mark Twain. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Last week, I hospitalized a patient against her will, based in part on what her family members told me she had threatened to do. The patient threatened to sue me and said I should have known that her relatives were lying. What if my patient is right? Could I face liability if I involuntarily hospitalized her based on bad collateral information?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

In all U.S. states, laws permit psychiatrists to involuntarily hospitalize persons who pose a danger to themselves or others because of mental illness.1 But taking this step can be tough. Deciding to hospitalize a patient against her will involves weighing her wants and freedom against your duty to look out for her long-term welfare and the community’s safety.2,3 Often, psychiatrists make these decisions under pressure because the family wants something done immediately, other patients also need attention, the clinical picture is incomplete, or potential dispositions (eg, crisis care and inpatient beds) are limited.3 Given such constraints, you can’t always make perfect decisions.

Dr. R’s question has 2 parts:

- What liabilities can a clinician face if a patient is wrongfully committed?

- What liabilities could arise from relying on inaccurate information or making a false petition in order to hospitalize a patient?

We hope that as you and Dr. R read our answers, you’ll have a clearer understanding of:

- the rationale for civil commitment

- how patients, doctors, and courts view civil commitment

- the role of collateral information in decision-making

- relevant legal concepts and case law.

Rationale for civil commitment

For centuries, society has used civil commitment as one of its legal methods for intervening when persons pose a danger to themselves or others because of their mental illness.4 Because incapacitation or death could result from a “false-negative” decision to release a dangerous patient, psychiatrists err on the side of caution and tolerate many “false-positive” hospitalizations of persons who wouldn’t have hurt anyone.5

We can never know if a patient would have done harm had she not been hospitalized. Measures of suicidality and hostility tend to subside during involuntary hospital treatment.6 After hospitalization, many patients cite protection from harm as a reason they are thankful for their treatment.7-9 Some involuntary inpatients want to be hospitalized but hide this for conscious or unconscious reasons,10,11 and involuntary treatment sometimes is the only way to help persons whose illness-induced anosognosia12 prevents them from understanding why they need treatment.13 Involuntary inpatient care leads to modest symptom reduction14,15 and produces treatment outcomes no worse than those of non-coerced patients.10

Patients’ views

Patients often view commitment as unjustified.16 They and their advocates object to what some view as the ultimate infringement on civil liberty.7,17 By its nature, involuntary commitment eliminates patients’ involvement in a major treatment decision,8 disempowers them,18 and influences their relationship with the treatment team.15

Some involuntary patients feel disrespected by staff members8 or experience inadvertent psychological harm, including “loss of self-esteem, identity, self-control, and self-efficacy, as well as diminished hope in the possibility of recovery.”15 Involuntary hospitalization also can have serious practical consequences. Commitment can lead to social stigma, loss of gun rights, increased risks of losing child custody, housing problems, and possible disqualification from some professions.19

Having seen many involuntary patients undergo a change of heart after treatment, psychiatrist Alan Stone proposed the “Thank You Theory” of civil commitment: involuntary hospitalization can be justified by showing that the patient is grateful after recovering.20 Studies show, however, that gratitude is far from universal.1

How coercion is experienced often depends on how it is communicated. The less coercion patients perceive, the better they feel about the treatment they received.21 Satisfaction is important because it leads to less compulsory readmission,22 and dissatisfaction makes malpractice lawsuits more likely.23

Commitment decision-making

States’ laws, judges’ attitudes, and court decisions establish each jurisdiction’s legal methods for instituting emergency holds and willingness to tolerate “false-positive” involuntary hospitalization,4,24 all of which create variation between and within states in how civil commitment laws are applied. As a result, clinicians’ decisions are influenced “by a range of social, political, and economic factors,”25 including patients’ sex, race, age, homelessness, employment status, living situation, diagnoses, previous involuntary treatment, and dissatisfaction with mental health treatment.22,26-32 Furthermore, the potential for coercion often blurs the line between an offer of voluntary admission and an involuntary hospitalization.18

Collateral information

Psychiatrists owe each patient a sound clinical assessment before deciding to initiate involuntarily hospitalization. During a psychiatric crisis, a patient might not be forthcoming or could have impaired memory or judgment. Information from friends or family can help fill in gaps in a patient’s self-report.33 As Dr. R’s question illustrates, adequate assessment often includes seeking information from persons familiar with the patient.1 A report on the Virginia Tech shootings by the Virginia Office of the Inspector General describes how collateral sources can provide otherwise missing evidence of dangerousness,34 and it often leads clinicians toward favoring admission.35

Yet clinicians should regard third-party reports with caution.36 As one attorney warns, “Psychiatrists should be cautious of the underlying motives of well-meaning family members and relatives.”37 If you make a decision to hospitalize a patient involuntarily based on collateral information that turns out to be flawed, are you at fault and potentially liable for harm to the patient?

False petitions and liability

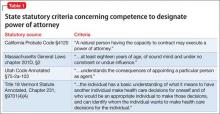

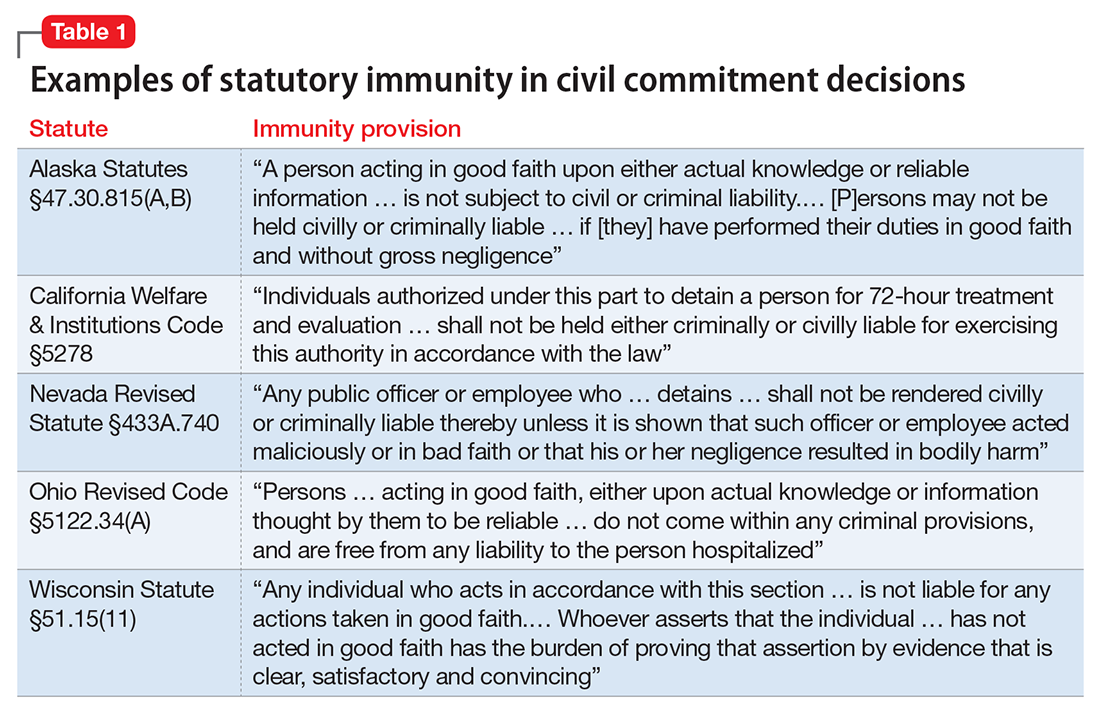

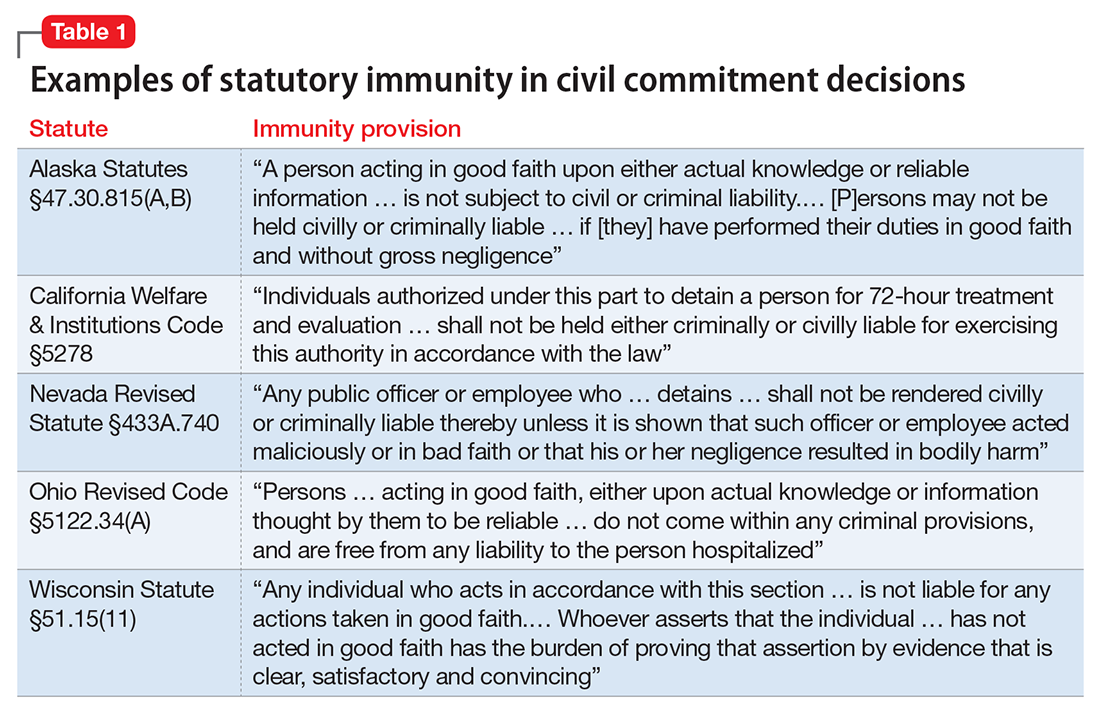

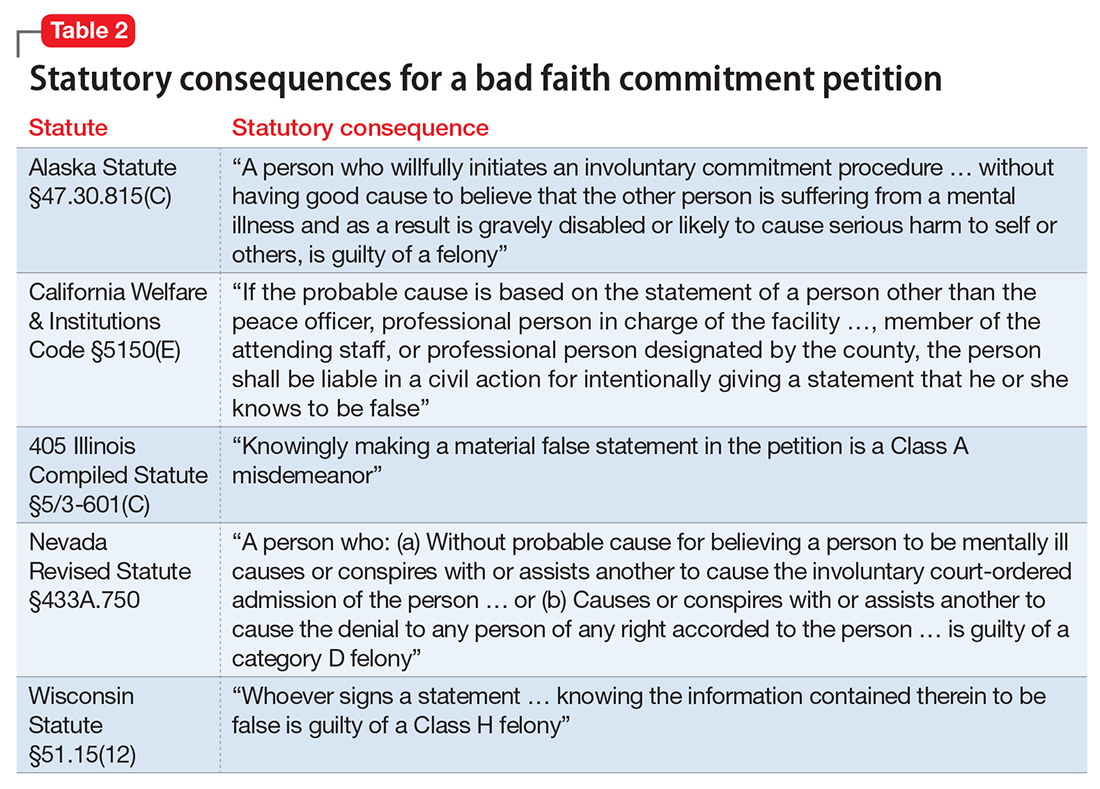

If you’re in a situation similar to the one Dr. R describes, you can take solace in knowing that courts generally provide immunity to a psychiatrist who makes a reasonable, well-intentioned decision to commit someone. The degree of immunity offered varies by jurisdiction. Table 1 provides examples of immunity language from several states’ statutes.

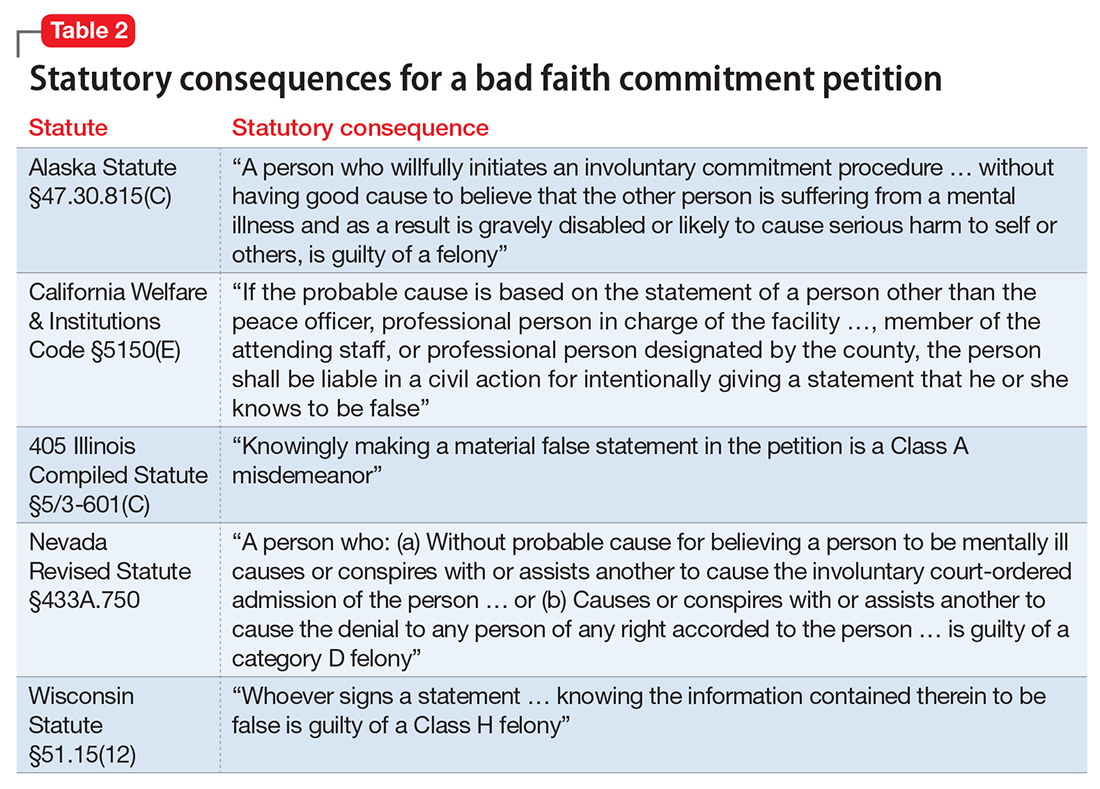

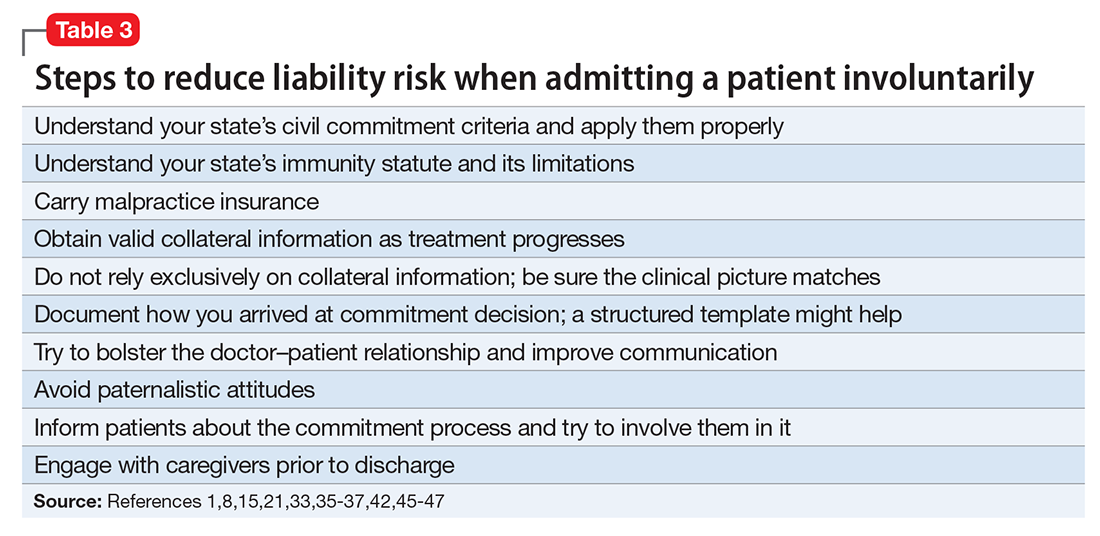

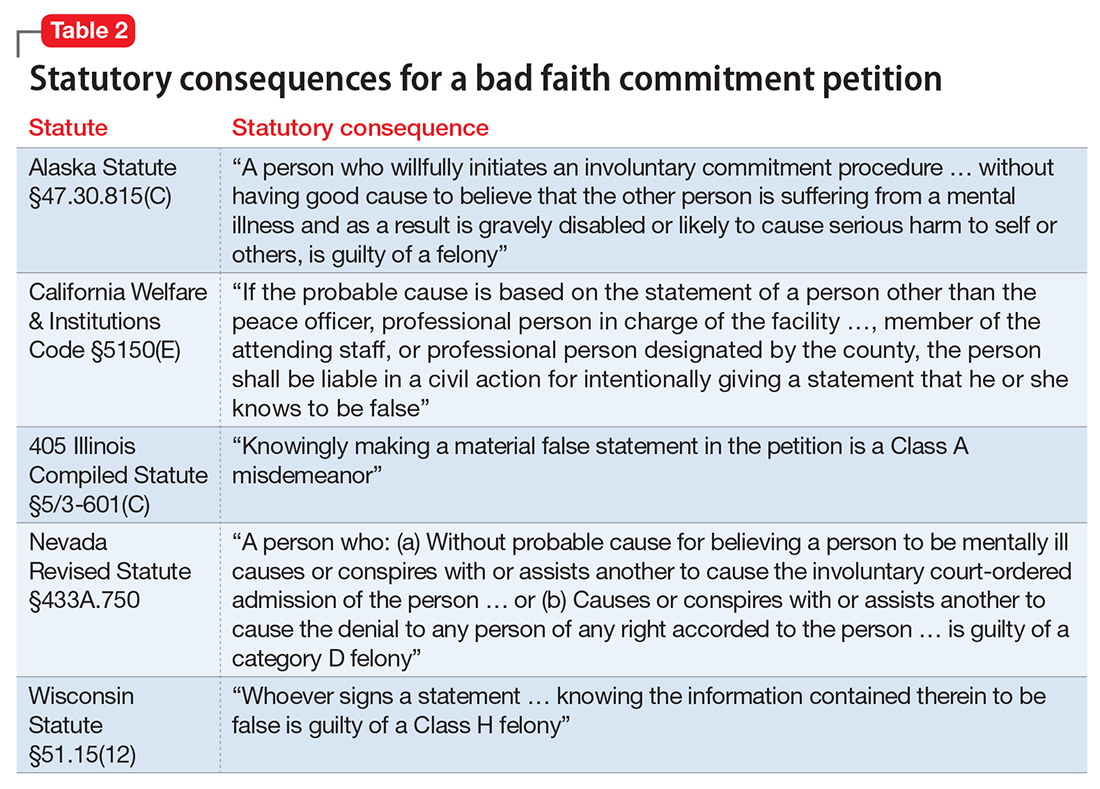

Many states’ statutes also lay out the potential consequences if a psychiatrist takes action to involuntarily hospitalize someone in bad faith or with malicious intent. In some jurisdictions, such actions can lead to criminal sanctions against the doctor or against the party who made a false petition (eg, a devious family member) (Table 2). Commenting on Texas’s statute, attorney Jeffrey Anderson explains, “The touchstone for causes of action based upon a wrongful civil commitment require that the psychiatrist[’s] conduct be found to be unreasonable and negligent. [Immunity…] still requires that a psychiatrist[’s] diagnosis of a patient[’s] threat to harm himself or others be a reasonable and prudent one.”37

The immunity extended through such statutes usually is limited to claims arising directly from the detention. For example, in the California case of Jacobs v Grossmont Hospital, a patient under a 72-hour hold fell and fractured her leg, and she sought damages. The trial court dismissed the suit under the immunity statute applicable to commitment decisions, but the appellate court held that “the immunity did not extend to other negligent acts.… The trial court erred in assuming that … the hospital was exempt from all liability for any negligence that occurred during the lawful hold.”38

Bingham v Cedars-Sinai Health Systems illustrates how physicians can lose immunity.39 A nurse contacted her supervisor to report a colleague who had stolen narcotics from work and compromised patient care. In response, the supervisor, hospital, and several physicians agreed to have her involuntarily committed. Later, it was confirmed that the colleague had taken the narcotics. She later sued the hospital system, claiming—in addition to malpractice—retaliation, invasion of privacy, assault and battery, false imprisonment, defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, disability-based harassment, and violation of her civil rights. Citing California’s immunity statute, the trial court granted summary judgment to the clinicians and hospital system. On appeal, however, the appellate court reversed the judgment, holding that the defendants had not shown that “the decision to detain Bingham was based on probable cause, a prerequisite to the exemption from liability,” and that Bingham had some legitimate grounds for her lawsuit.

A key point for Dr. R to consider is that, although some states provide immunity if the psychiatrist’s admitting decision was based on an evaluation “performed in good faith,”40 other states’ immunity provisions apply only if the psychiatrist had probable cause to make a decision to detain.41

Ways to reduce liability risk

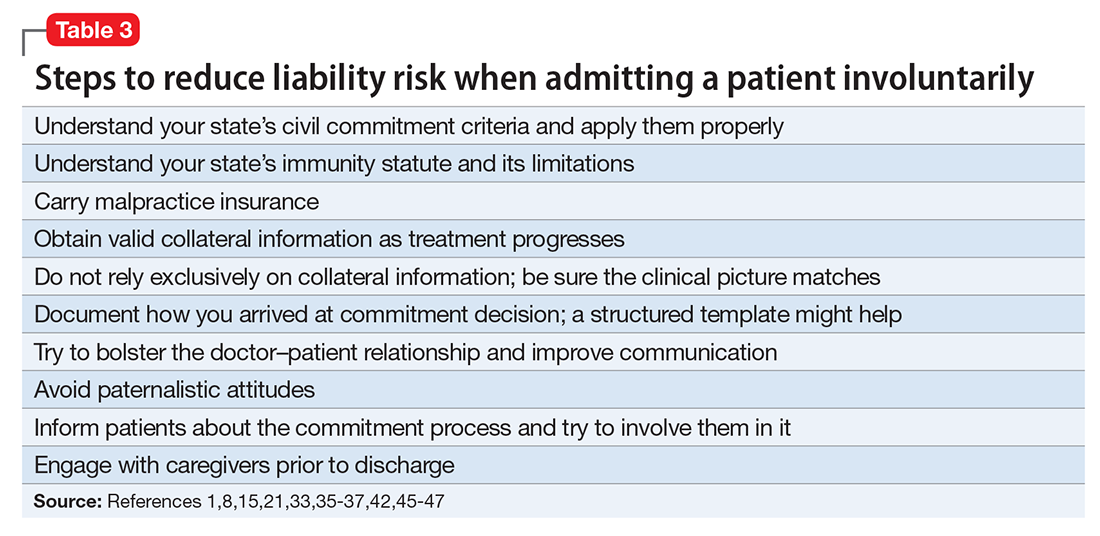

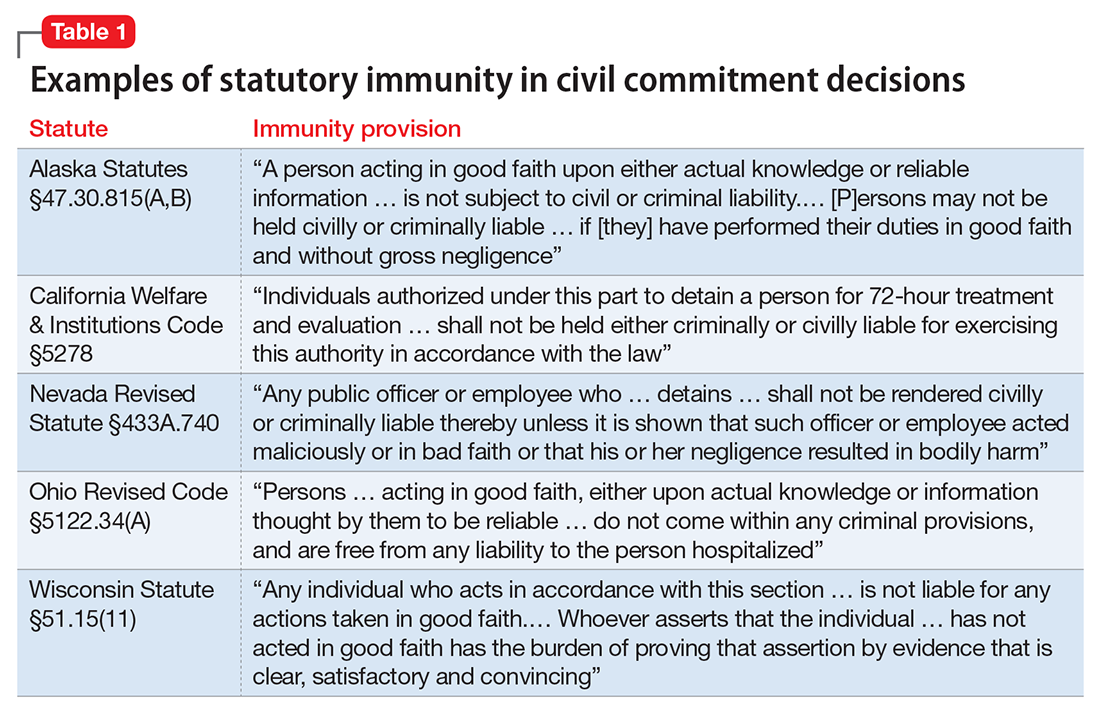

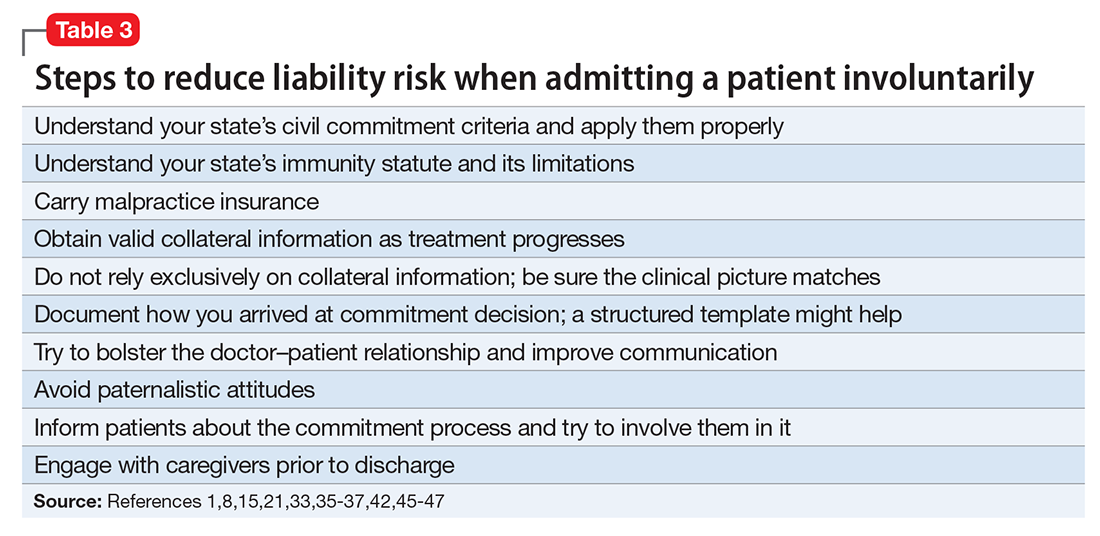

Although an involuntary hospitalization could have an uncertain basis, psychiatrists can reduce the risk of legal liability for their decisions. Good documentation is important. Admitting psychiatrists usually make sound decisions, but the corresponding documentation frequently lacks clinical justification.42-44 As the rate of appropriate documentation of admission decision-making improves, the rate of commitment falls,44 and patients’ legal rights enjoy greater protection.43 Poor communication can decrease the quality of care and increase the risk of a malpractice lawsuit.45 This is just one of many reasons why you should explain your reasons for involuntary hospitalization and inform patients of the procedures for judicial review.8,9 Table 3 summarizes other steps to reduce liability risk when committing patients to the hospital.1,8,15,21,33,35-37,42,45-47

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment: best practices for forensic mental health assessments. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

2. Testa M, West SG. Civil commitment in the United States. Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2010;7(10):30-40.

3. Hedman LC, Petrila J, Fisher WH, et al. State laws on emergency holds for mental health stabilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):529-535.

4. Groendyk Z. “It takes a lot to get into Bellevue”: a pro-rights critique of New York’s involuntary commitment law. Fordham Urban Law J. 2013;40(1):548-585.

5. Brooks RA. U.S. psychiatrists’ beliefs and wants about involuntary civil commitment grounds. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2006;29(1):13-21.

6. Giacco D, Priebe S. Suicidality and hostility following involuntary hospital treatment. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154458.

7. Wyder M, Bland R, Herriot A, et al. The experiences of the legal processes of involuntary treatment orders: tension between the legal and medical frameworks. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2015;38:44-50.

8. Valenti E, Giacco D, Katasakou C, et al. Which values are important for patients during involuntary treatment? A qualitative study with psychiatric inpatients. J Med Ethics. 2014;40(12):832-836.

9. Katsakou C, Rose D, Amos T, et al. Psychiatric patients’ views on why their involuntary hospitalisation was right or wrong: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;42(7):1169-1179.

10. Kaltiala-Heino R, Laippala P, Salokangas RK. Impact of coercion on treatment outcome. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1997;20(3):311-322.

11. Hoge SK, Lidz CW, Eisenberg M, et al. Perceptions of coercion in the admission of voluntary and involuntary psychiatric patients. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1997;20(2):167-181.

12. Lehrer DS, Lorenz J. Anosognosia in schizophrenia: hidden in plain sight. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(5-6):10-17. 13. Gordon S. The danger zone: how the dangerousness standard in civil commitment proceedings harms people with serious mental illness. Case Western Reserve Law Review. 2016;66(3):657-700.

14. Kallert TW, Katsakou C, Adamowski T, et al. Coerced hospital admission and symptom change—a prospective observational multi-centre study. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028191.

15. Danzer G, Wilkus-Stone A. The give and take of freedom: the role of involuntary hospitalization and treatment in recovery from mental illness. Bull Menninger Clin. 2015;79(3):255-280.

16. Roe D, Weishut DJ, Jaglom M, et al. Patients’ and staff members’ attitudes about the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(1):87-91.

17. Amidov T. Involuntary commitment is unnecessary and discriminatory. In: Berlatsky N, ed. Mental illness. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press; 2016;140-145.

18. Monahan J, Hoge SK, Lidz C, et al. Coercion and commitment: understanding involuntary mental hospital admission. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1995;18(3):249-263.

19. Guest Pryal KR. Heller’s scapegoats. North Carolina Law Review. 2015;93(5):1439-1473.

20. Stone AA. Mental health and law: a system in transition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1975:75-176.

21. Katsakou C, Bowers L, Amos T, et al. Coercion and treatment satisfaction among involuntary patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(3):286-292.

22. Setkowski K, van der Post LF, Peen J, et al. Changing patient perspectives after compulsory admission and the risk of re-admission during 5 years of follow-up: the Amsterdam study of acute psychiatry IX. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(6):578-588.

23. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-1133.

24. Goldman A. Continued overreliance on involuntary commitment: the need for a less restrictive alternative. J Leg Med. 2015;36(2):233-251.

25. Fisher WH, Grisso T. Commentary: civil commitment statutes—40 years of circumvention. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):365-368.

26. Curley A, Agada E, Emechebe A, et al. Exploring and explaining involuntary care: the relationship between psychiatric admission status, gender and other demographic and clinical variables. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2016;47:53-59.

27. Muroff JR, Jackson JS, Mowbray CT, et al. The influence of gender, patient volume and time on clinical diagnostic decision making in psychiatric emergency services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(6):481-488.

28. Muroff JR, Edelsohn GA, Joe S, et al. The role of race in diagnostic and disposition decision making in a pediatric psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(3):269-276.

29. Unick GJ, Kessell E, Woodard EK, et al. Factors affecting psychiatric inpatient hospitalization from a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(6):618-625.

30. Ng XT, Kelly BD. Voluntary and involuntary care: three-year study of demographic and diagnostic admission statistics at an inner-city adult psychiatry unit. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35(4):317-326.

31. Lo TT, Woo BK. The impact of unemployment on utilization of psychiatric emergency services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(3):e7-e8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.010.

32. van der Post LFM, Peen J, Dekker JJ. A prediction model for the incidence of civil detention for crisis patients with psychiatric illnesses; the Amsterdam study of acute psychiatry VII. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(2):283-290.

33. Heilbrun K, NeMoyer A, King C, et al. Using third-party information in forensic mental health assessment: a critical review. Court Review. 2015;51(1):16-35.

34. Mass shootings at Virginia Tech, April 16, 2007 report of the Virginia Tech Review Panel presented to Timothy M. Kaine, Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia. http://cdm16064.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p266901coll4/id/904. Accessed February 2, 2017.

35. Segal SP, Laurie TA, Segal MJ. Factors in the use of coercive retention in civil commitment evaluations in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):514-520.

36. Lincoln A, Allen MH. The influence of collateral information on access to inpatient psychiatric services. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 2002;6:99-108.

37. Anderson JC. How I decided to sue you: misadventures in psychiatry. Reprinted in part from: Moody CE, Smith MT, Maedgen BJ. Litigation of psychiatric malpractice claims. Presented at: Medical Malpractice Conference; April 15, 1993; San Antonio, TX. http://www.texaslawfirm.com/Articles/How_I_Decided_to_Sue_You__Misadventrues_in_Psychiatry.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2016.

38. Jacobs v Grossmont Hospital, 108 Cal App 4th 69, 133 Cal Rptr 2d9 (2003).

39. Bingham v Cedars Sinai Health Systems, WL 2137442, Cal App 2 Dist (2004).

40. Ohio Revised Code §5122.34.

41. California Welfare & Institutions Code §5150(E).

42. Hashmi A, Shad M, Rhoades HM, et al. Involuntary detention: do psychiatrists clinically justify continuing involuntary hospitalization? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):285-293.

43. Brayley J, Alston A, Rogers K. Legal criteria for involuntary mental health admission: clinician performance in recording grounds for decision. Med J Aust. 2015;203(8):334.

44. Perrigo TL, Williams KA. Implementation of an evidence based guideline for assessment and documentation of the civil commitment process. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(8):1033-1036.

45. Mor S, Rabinovich-Einy O. Relational malpractice. Seton Hall Law Rev. 2012;42(2):601-642.

46. Tate v Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, WL 176625, U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5891 (CD Cal 2014).

47. Ranieri V, Madigan K, Roche E, et al. Caregivers’ perceptions of coercion in psychiatric hospital admission. Psychiatry Res. 2015;22(3)8:380-385.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Last week, I hospitalized a patient against her will, based in part on what her family members told me she had threatened to do. The patient threatened to sue me and said I should have known that her relatives were lying. What if my patient is right? Could I face liability if I involuntarily hospitalized her based on bad collateral information?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

In all U.S. states, laws permit psychiatrists to involuntarily hospitalize persons who pose a danger to themselves or others because of mental illness.1 But taking this step can be tough. Deciding to hospitalize a patient against her will involves weighing her wants and freedom against your duty to look out for her long-term welfare and the community’s safety.2,3 Often, psychiatrists make these decisions under pressure because the family wants something done immediately, other patients also need attention, the clinical picture is incomplete, or potential dispositions (eg, crisis care and inpatient beds) are limited.3 Given such constraints, you can’t always make perfect decisions.

Dr. R’s question has 2 parts:

- What liabilities can a clinician face if a patient is wrongfully committed?

- What liabilities could arise from relying on inaccurate information or making a false petition in order to hospitalize a patient?

We hope that as you and Dr. R read our answers, you’ll have a clearer understanding of:

- the rationale for civil commitment

- how patients, doctors, and courts view civil commitment

- the role of collateral information in decision-making

- relevant legal concepts and case law.

Rationale for civil commitment

For centuries, society has used civil commitment as one of its legal methods for intervening when persons pose a danger to themselves or others because of their mental illness.4 Because incapacitation or death could result from a “false-negative” decision to release a dangerous patient, psychiatrists err on the side of caution and tolerate many “false-positive” hospitalizations of persons who wouldn’t have hurt anyone.5

We can never know if a patient would have done harm had she not been hospitalized. Measures of suicidality and hostility tend to subside during involuntary hospital treatment.6 After hospitalization, many patients cite protection from harm as a reason they are thankful for their treatment.7-9 Some involuntary inpatients want to be hospitalized but hide this for conscious or unconscious reasons,10,11 and involuntary treatment sometimes is the only way to help persons whose illness-induced anosognosia12 prevents them from understanding why they need treatment.13 Involuntary inpatient care leads to modest symptom reduction14,15 and produces treatment outcomes no worse than those of non-coerced patients.10

Patients’ views

Patients often view commitment as unjustified.16 They and their advocates object to what some view as the ultimate infringement on civil liberty.7,17 By its nature, involuntary commitment eliminates patients’ involvement in a major treatment decision,8 disempowers them,18 and influences their relationship with the treatment team.15

Some involuntary patients feel disrespected by staff members8 or experience inadvertent psychological harm, including “loss of self-esteem, identity, self-control, and self-efficacy, as well as diminished hope in the possibility of recovery.”15 Involuntary hospitalization also can have serious practical consequences. Commitment can lead to social stigma, loss of gun rights, increased risks of losing child custody, housing problems, and possible disqualification from some professions.19

Having seen many involuntary patients undergo a change of heart after treatment, psychiatrist Alan Stone proposed the “Thank You Theory” of civil commitment: involuntary hospitalization can be justified by showing that the patient is grateful after recovering.20 Studies show, however, that gratitude is far from universal.1

How coercion is experienced often depends on how it is communicated. The less coercion patients perceive, the better they feel about the treatment they received.21 Satisfaction is important because it leads to less compulsory readmission,22 and dissatisfaction makes malpractice lawsuits more likely.23

Commitment decision-making

States’ laws, judges’ attitudes, and court decisions establish each jurisdiction’s legal methods for instituting emergency holds and willingness to tolerate “false-positive” involuntary hospitalization,4,24 all of which create variation between and within states in how civil commitment laws are applied. As a result, clinicians’ decisions are influenced “by a range of social, political, and economic factors,”25 including patients’ sex, race, age, homelessness, employment status, living situation, diagnoses, previous involuntary treatment, and dissatisfaction with mental health treatment.22,26-32 Furthermore, the potential for coercion often blurs the line between an offer of voluntary admission and an involuntary hospitalization.18

Collateral information

Psychiatrists owe each patient a sound clinical assessment before deciding to initiate involuntarily hospitalization. During a psychiatric crisis, a patient might not be forthcoming or could have impaired memory or judgment. Information from friends or family can help fill in gaps in a patient’s self-report.33 As Dr. R’s question illustrates, adequate assessment often includes seeking information from persons familiar with the patient.1 A report on the Virginia Tech shootings by the Virginia Office of the Inspector General describes how collateral sources can provide otherwise missing evidence of dangerousness,34 and it often leads clinicians toward favoring admission.35

Yet clinicians should regard third-party reports with caution.36 As one attorney warns, “Psychiatrists should be cautious of the underlying motives of well-meaning family members and relatives.”37 If you make a decision to hospitalize a patient involuntarily based on collateral information that turns out to be flawed, are you at fault and potentially liable for harm to the patient?

False petitions and liability

If you’re in a situation similar to the one Dr. R describes, you can take solace in knowing that courts generally provide immunity to a psychiatrist who makes a reasonable, well-intentioned decision to commit someone. The degree of immunity offered varies by jurisdiction. Table 1 provides examples of immunity language from several states’ statutes.

Many states’ statutes also lay out the potential consequences if a psychiatrist takes action to involuntarily hospitalize someone in bad faith or with malicious intent. In some jurisdictions, such actions can lead to criminal sanctions against the doctor or against the party who made a false petition (eg, a devious family member) (Table 2). Commenting on Texas’s statute, attorney Jeffrey Anderson explains, “The touchstone for causes of action based upon a wrongful civil commitment require that the psychiatrist[’s] conduct be found to be unreasonable and negligent. [Immunity…] still requires that a psychiatrist[’s] diagnosis of a patient[’s] threat to harm himself or others be a reasonable and prudent one.”37

The immunity extended through such statutes usually is limited to claims arising directly from the detention. For example, in the California case of Jacobs v Grossmont Hospital, a patient under a 72-hour hold fell and fractured her leg, and she sought damages. The trial court dismissed the suit under the immunity statute applicable to commitment decisions, but the appellate court held that “the immunity did not extend to other negligent acts.… The trial court erred in assuming that … the hospital was exempt from all liability for any negligence that occurred during the lawful hold.”38

Bingham v Cedars-Sinai Health Systems illustrates how physicians can lose immunity.39 A nurse contacted her supervisor to report a colleague who had stolen narcotics from work and compromised patient care. In response, the supervisor, hospital, and several physicians agreed to have her involuntarily committed. Later, it was confirmed that the colleague had taken the narcotics. She later sued the hospital system, claiming—in addition to malpractice—retaliation, invasion of privacy, assault and battery, false imprisonment, defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, disability-based harassment, and violation of her civil rights. Citing California’s immunity statute, the trial court granted summary judgment to the clinicians and hospital system. On appeal, however, the appellate court reversed the judgment, holding that the defendants had not shown that “the decision to detain Bingham was based on probable cause, a prerequisite to the exemption from liability,” and that Bingham had some legitimate grounds for her lawsuit.

A key point for Dr. R to consider is that, although some states provide immunity if the psychiatrist’s admitting decision was based on an evaluation “performed in good faith,”40 other states’ immunity provisions apply only if the psychiatrist had probable cause to make a decision to detain.41

Ways to reduce liability risk

Although an involuntary hospitalization could have an uncertain basis, psychiatrists can reduce the risk of legal liability for their decisions. Good documentation is important. Admitting psychiatrists usually make sound decisions, but the corresponding documentation frequently lacks clinical justification.42-44 As the rate of appropriate documentation of admission decision-making improves, the rate of commitment falls,44 and patients’ legal rights enjoy greater protection.43 Poor communication can decrease the quality of care and increase the risk of a malpractice lawsuit.45 This is just one of many reasons why you should explain your reasons for involuntary hospitalization and inform patients of the procedures for judicial review.8,9 Table 3 summarizes other steps to reduce liability risk when committing patients to the hospital.1,8,15,21,33,35-37,42,45-47

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Last week, I hospitalized a patient against her will, based in part on what her family members told me she had threatened to do. The patient threatened to sue me and said I should have known that her relatives were lying. What if my patient is right? Could I face liability if I involuntarily hospitalized her based on bad collateral information?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

In all U.S. states, laws permit psychiatrists to involuntarily hospitalize persons who pose a danger to themselves or others because of mental illness.1 But taking this step can be tough. Deciding to hospitalize a patient against her will involves weighing her wants and freedom against your duty to look out for her long-term welfare and the community’s safety.2,3 Often, psychiatrists make these decisions under pressure because the family wants something done immediately, other patients also need attention, the clinical picture is incomplete, or potential dispositions (eg, crisis care and inpatient beds) are limited.3 Given such constraints, you can’t always make perfect decisions.

Dr. R’s question has 2 parts:

- What liabilities can a clinician face if a patient is wrongfully committed?

- What liabilities could arise from relying on inaccurate information or making a false petition in order to hospitalize a patient?

We hope that as you and Dr. R read our answers, you’ll have a clearer understanding of:

- the rationale for civil commitment

- how patients, doctors, and courts view civil commitment

- the role of collateral information in decision-making

- relevant legal concepts and case law.

Rationale for civil commitment

For centuries, society has used civil commitment as one of its legal methods for intervening when persons pose a danger to themselves or others because of their mental illness.4 Because incapacitation or death could result from a “false-negative” decision to release a dangerous patient, psychiatrists err on the side of caution and tolerate many “false-positive” hospitalizations of persons who wouldn’t have hurt anyone.5

We can never know if a patient would have done harm had she not been hospitalized. Measures of suicidality and hostility tend to subside during involuntary hospital treatment.6 After hospitalization, many patients cite protection from harm as a reason they are thankful for their treatment.7-9 Some involuntary inpatients want to be hospitalized but hide this for conscious or unconscious reasons,10,11 and involuntary treatment sometimes is the only way to help persons whose illness-induced anosognosia12 prevents them from understanding why they need treatment.13 Involuntary inpatient care leads to modest symptom reduction14,15 and produces treatment outcomes no worse than those of non-coerced patients.10

Patients’ views

Patients often view commitment as unjustified.16 They and their advocates object to what some view as the ultimate infringement on civil liberty.7,17 By its nature, involuntary commitment eliminates patients’ involvement in a major treatment decision,8 disempowers them,18 and influences their relationship with the treatment team.15

Some involuntary patients feel disrespected by staff members8 or experience inadvertent psychological harm, including “loss of self-esteem, identity, self-control, and self-efficacy, as well as diminished hope in the possibility of recovery.”15 Involuntary hospitalization also can have serious practical consequences. Commitment can lead to social stigma, loss of gun rights, increased risks of losing child custody, housing problems, and possible disqualification from some professions.19