User login

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

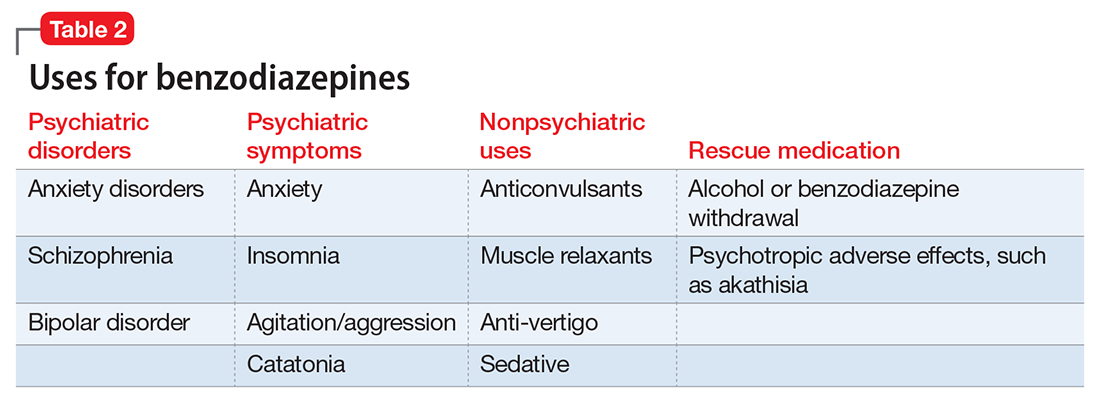

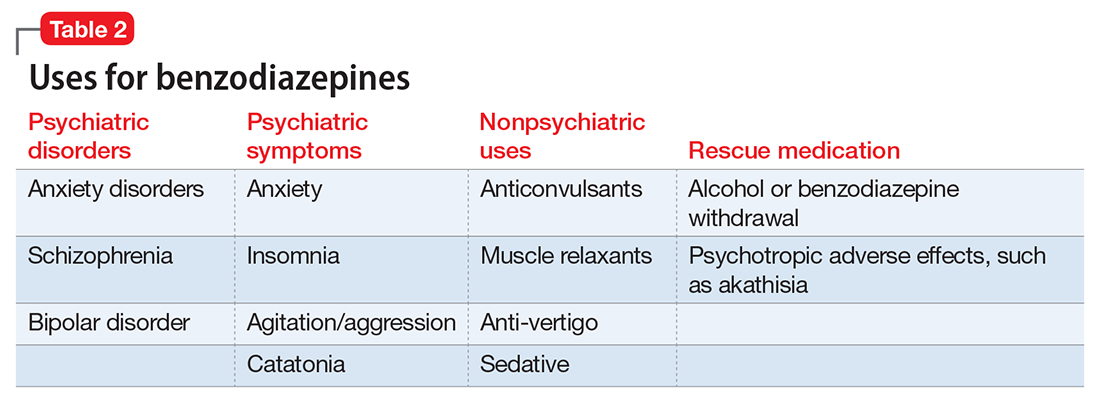

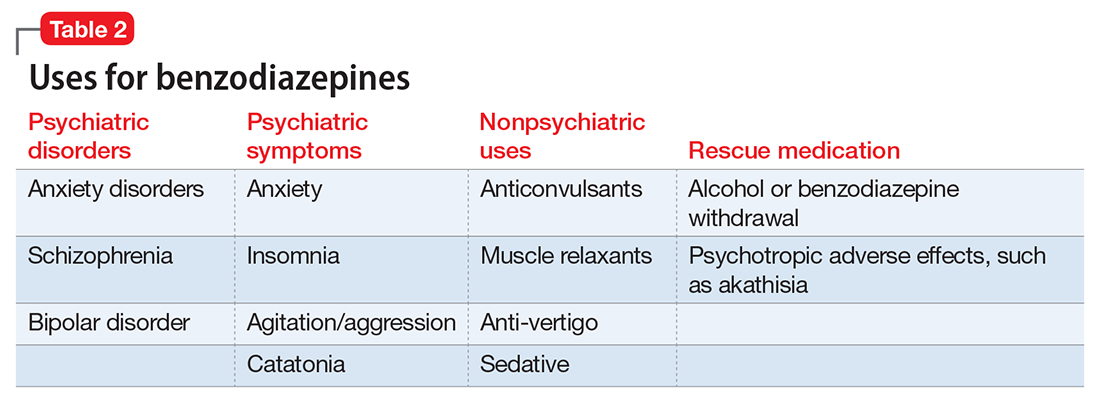

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

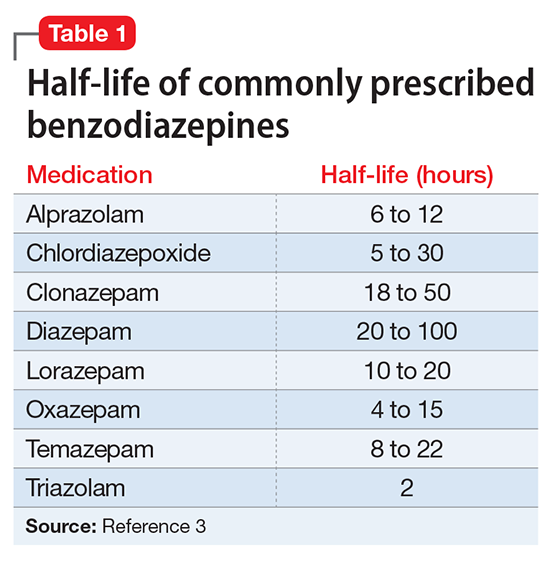

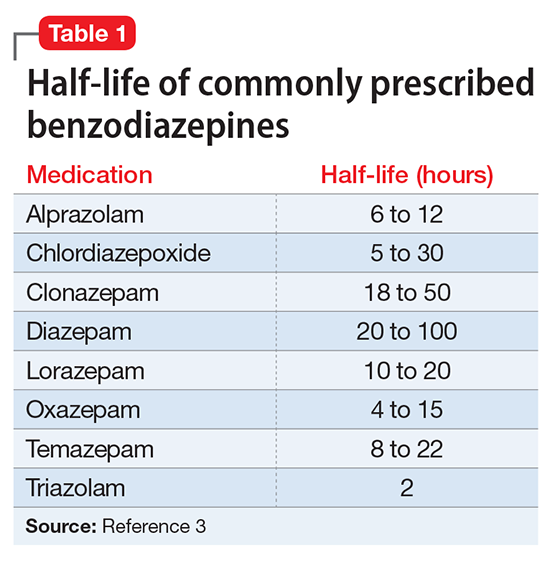

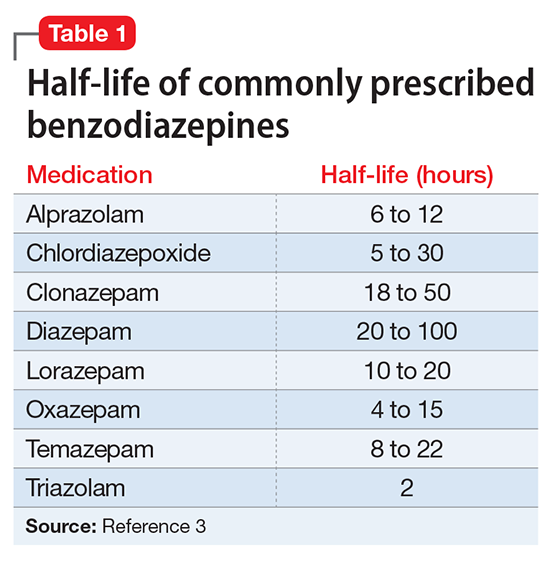

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

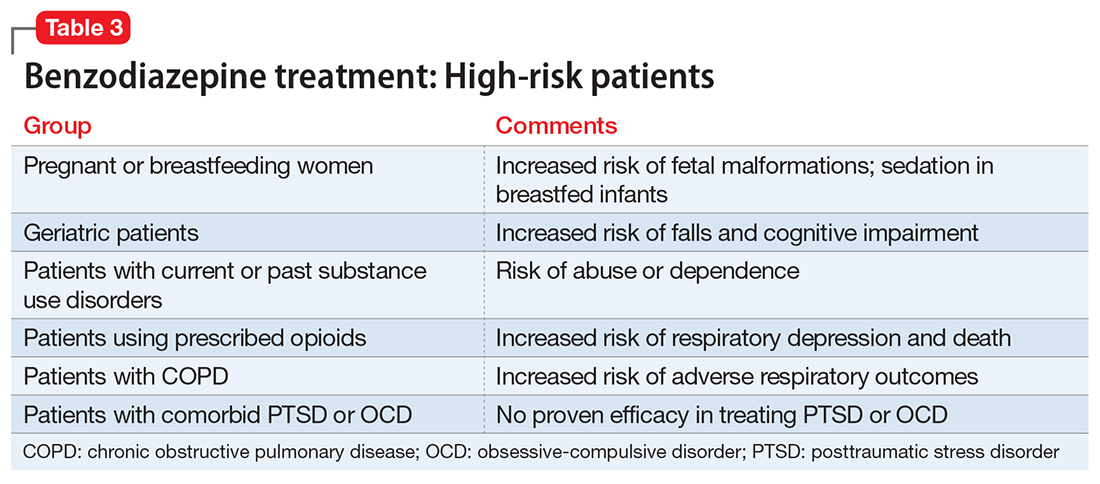

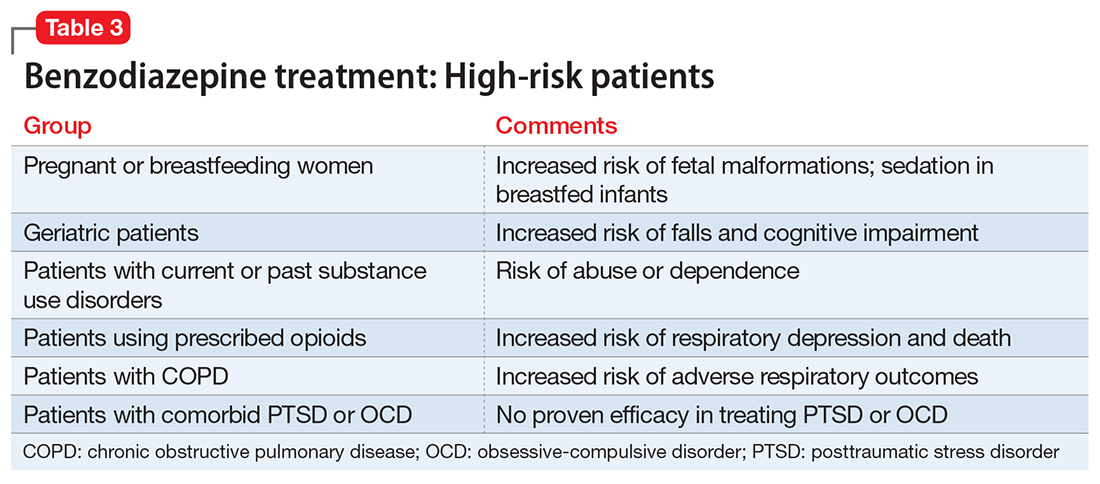

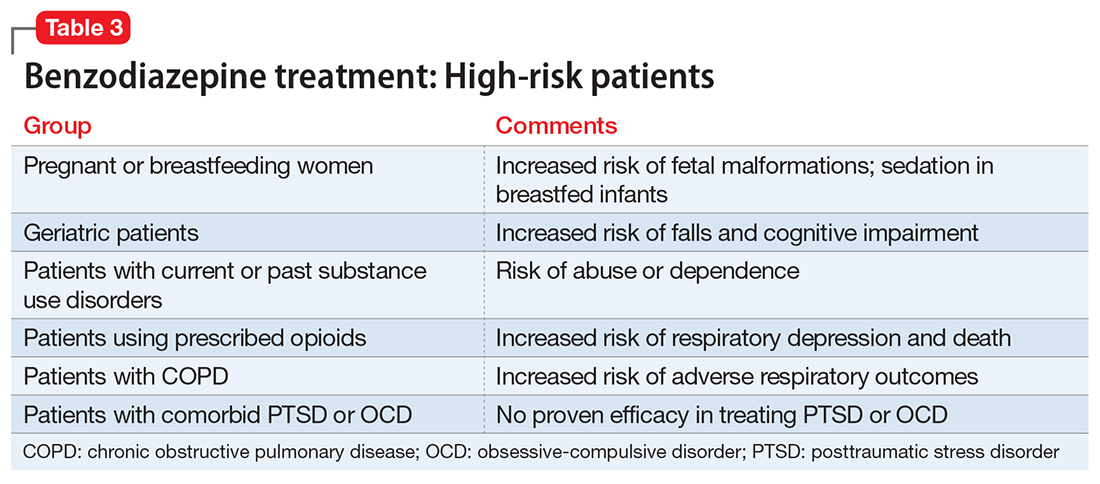

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

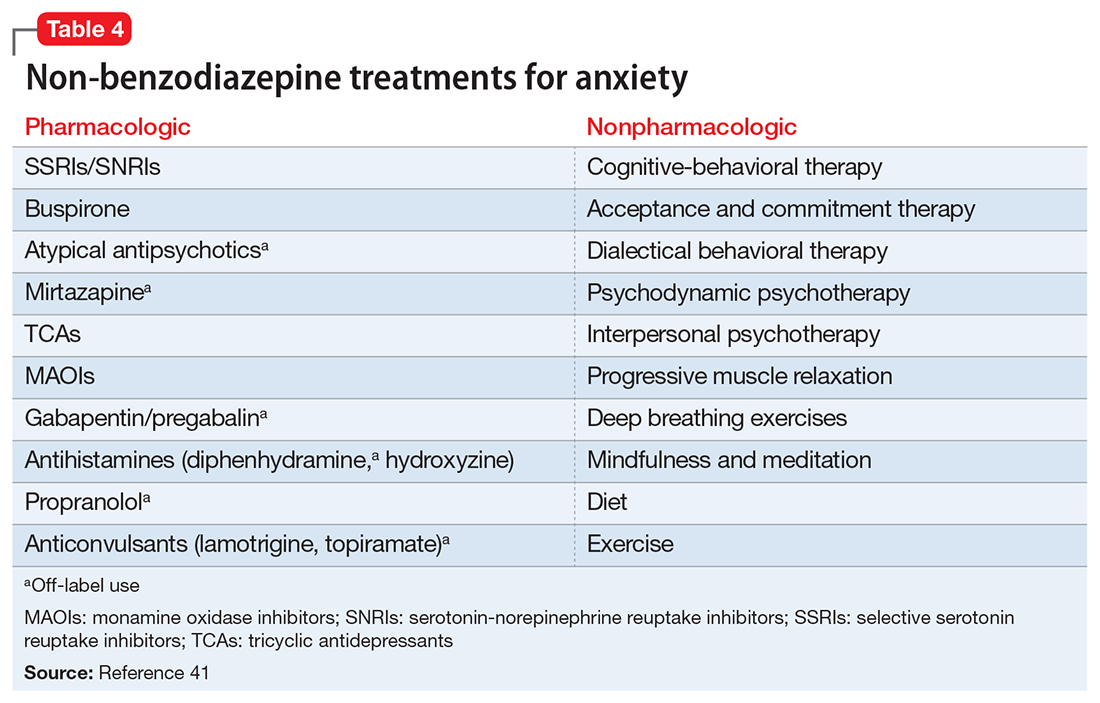

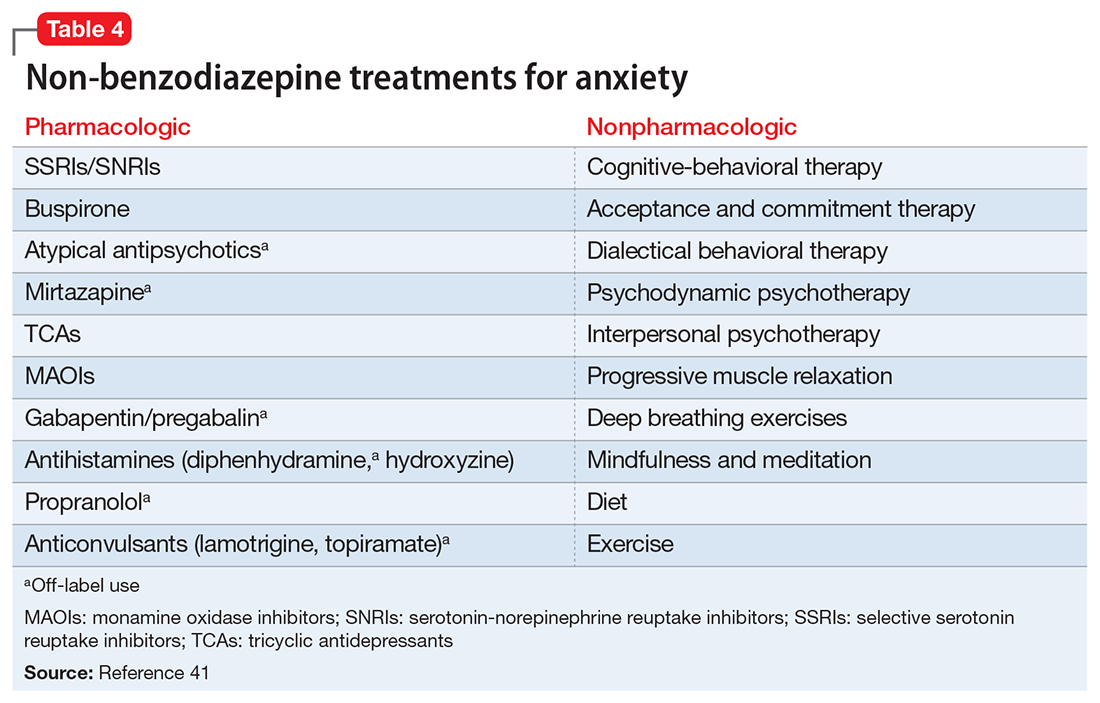

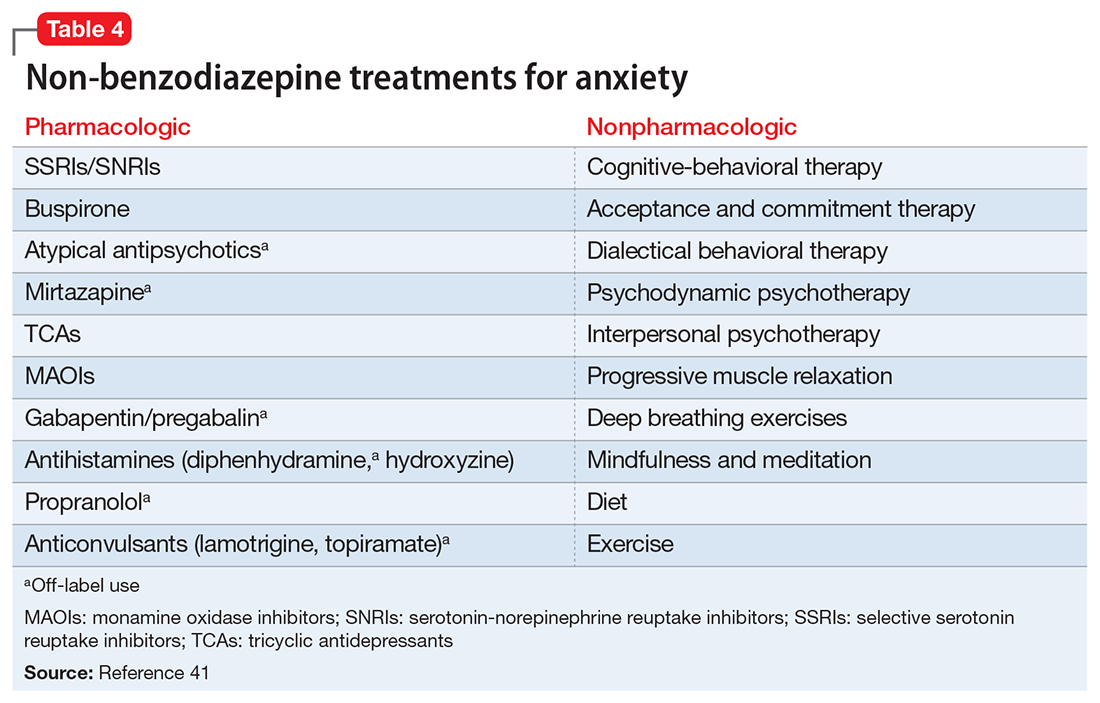

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

As a group, anxiety disorders are the most common mental illness in the Unites States, affecting 40 million adults. There is a nearly 30% lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population.1 DSM-5 anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. Although DSM-IV-TR also classified obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were reclassified in DSM-5. Anxiety also is a frequent symptom of many other psychiatric disorders, especially major depressive disorder.

Although benzodiazepines have many potential uses, they also carry risks that prescribers should recognize. This article reviews some of the risks of benzodiazepine use, identifies patients with higher risks of adverse effects, and presents a practical approach to prescribing these medications.

A wide range of risks

Abuse and addiction. Perhaps the most commonly recognized risk associated with benzodiazepine use is the potential for abuse and addiction.4 Prolonged benzodiazepine use typically results in physiologic tolerance, requiring higher dosing to achieve the same initial effect.5 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recognize the potential for benzodiazepine use to result in symptoms of dependence, including cravings and withdrawal, stating that “with ongoing use, all benzodiazepines will produce physiological dependence in most patients.”6 High-potency, short-acting compounds such as alprazolam have a higher risk for dependence, toxicity, and abuse.7 However, long-acting benzodiazepines (such as clonazepam) also can be habit-forming.8 Because of these properties, it is generally advisable to avoid prescribing benzodiazepines (and short-acting compounds in particular) when treating patients with current or past substance use disorders, except when treating withdrawal.9

Limited efficacy for other disorders. Although benzodiazepines can help reduce anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders, they have shown less promise in treating other disorders in which anxiety is a common symptom. Treating PTSD with benzodiazepines does not appear to offer any advantage over placebo, and may even result in increased symptoms over time.10,11 There is limited evidence supporting the use of benzodiazepines to treat OCD.12,13 Patients with borderline personality disorder who are treated with benzodiazepines may experience an increase in behavioral dysregulation.14

Physical ailments. Benzodiazepines can affect comorbid physical ailments. One study found that long-term benzodiazepine use among patients with comorbid pain disorders was correlated with high utilization of medical services and high disability levels.15 Benzodiazepine use also has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbating respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,16 and increased risk of pneumonia.17,18

Pregnancy and breastfeeding. Benzodiazepines carry risks for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Benzodiazepine use during pregnancy may increase the relative risk of major malformations and oral clefts. It also may result in neonatal lethargy, sedation, and weight loss. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can occur in the neonate.19 Benzodiazepines are secreted in breast milk and can result in sedation among breastfed infants.20

Geriatric patients. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults recommends against prescribing benzodiazepines to geriatric patients.21 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with an increased risk for falls among older adults,22,23 with an increased risk of fractures24 that can be fatal.25 Benzodiazepines also have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive dysfunction and dementia.26,27 Despite the documented risks of using benzodiazepines in geriatric patients, benzodiazepines continue to be frequently prescribed to this age group.28,29 One study found that the rate of prescribing benzodiazepines by primary care physicians increased from 2003 to 2012, primarily among older adults with no diagnosis of pain or a psychiatric disorder.30

Mortality. Benzodiazepine use also carries an increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine users are at increased risk of motor vehicle accidents because of difficulty maintaining road position.31 Some research has shown that patients with schizophrenia treated with benzodiazepines have an increased risk of death compared with those who are prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants.32 Another study showed that patients with schizophrenia who were prescribed benzodiazepines had a greater risk of death by suicide and accidental poisoning.33 Benzodiazepine use has been associated with suicidal ideation and an increased risk of suicide.34 Prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are the top 2 causes of overdose-related deaths (benzodiazepines are involved in approximately 31% of fatal overdoses35), and from 2002 to 2015 there was a 4.3-fold increase in deaths from benzodiazepine overdose in the United States.36 CDC guidelines recommend against co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines because of the risk of death by respiratory depression.37 As of August 2016, the FDA required black-box warnings for opioids and benzodiazepines regarding the risk of respiratory depression and death when these agents are used in combination, noting that “If these medicines are prescribed together, limit the dosages and duration of each drug to the minimum possible while achieving the desired clinical effect.”38,39

A sensible approach to prescribing

Given the risks posed by benzodiazepines, what would constitute a sensible approach to their use? Clearly, there are some patients for whom benzodiazepine use should be minimized or avoided (Table 3). In a patient who is deemed a good candidate for benzodiazepines, a long-acting agent may be preferable because of the increased risk of dependence associated with short-acting compounds. Start with a low dose, and use the lowest dose that adequately treats the patient’s symptoms.40 Using scheduled rather than “as-needed” dosing may help reduce behavioral escape patterns that reinforce anxiety and dependence in the long term.

Before starting a patient on a benzodiazepine, discuss with him (her) the risks of use and an exit plan to discontinue the medication. For example, a benzodiazepine may be prescribed at the same time as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), with the goal of weaning off the benzodiazepine once the SSRI has achieved efficacy.6 Inform the patient that prescribing or treatment may be terminated if it is discovered that the patient is abusing or diverting the medication (regularly reviewing the state prescription monitoring program database can help determine if this has occurred). Strongly consider using non-benzodiazepine treatments for anxiety with (or eventually in place of) benzodiazepines (Table 441).

Reducing or stopping benzodiazepines can be challenging.42 Patients often are reluctant to stop such medications, and abrupt cessation can cause severe withdrawal. Benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms can be severe or even fatal. Therefore, a safe and collaborative approach to reducing or stopping benzodiazepines is necessary. A starting point might be to review the risks associated with benzodiazepine use with the patient and ask about the frequency of use. Discuss with the patient a slow taper, perhaps reducing the dose by 10% to 25% increments weekly to biweekly.43,44 Less motivated patients may require a slower taper, more time, or repeated discussions. When starting a dose reduction, notify the patient that some rebound anxiety or insomnia are to be expected. With any progress the patient makes toward reducing his usage, congratulate him on such progress.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Balon R, Fava GA, Rickels K. Need for a realistic appraisal of benzodiazepines. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):243-244.

3. Ashton CH. Benzodiazepine equivalence table. http://www.benzo.org.uk/bzequiv.htm. Revised April 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Commonly abused drugs. https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/commonly_abused_drugs_3.pdf. Revised January 2016. Accessed January 9, 2018.

5. Licata SC, Rowlett JK. Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABA(A) receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90(1):74-89.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Published January 2009. Accessed May 3, 2017.

7. Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152.

8. Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, Gaynes BN, et al. Simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use and subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in adults with depression, United States, 2001-2014. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):747-755.

9. O’Brien PL, Karnell LH, Gokhale M, et al. Prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids to individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:223-230.

10. Mellman TA, Bustamante V, David D, et al. Hypnotic medication in the aftermath of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(12):1183-1184.

11. Gelpin E, Bonne O, Peri T, et al. Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(9):390-394.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf. Published July 2007. Accessed May 3, 2017.

13. Abdel-Ahad P, Kazour F. Non-antidepressant pharmacological treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a comprehensive review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2015;10(2):97-111.

14. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Alprazolam-induced dyscontrol in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(1):98-100.

15. Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, et al. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(3):180-192.

16. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

17. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax. 2013;68(2):163-170.

18. Taipale H, Tolppanen AM, Koponen M, et al. Risk of pneumonia associated with incident benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling adults with Alzheimer disease. CMAJ. 2017;189(14):E519-E529.

19. Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T. Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant. Psychiatric Serv. 2002;53:39-49.

20. U.S. National Library of Medicine, TOXNET Toxicology Data Network. Lactmed: alprazolam. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/r?dbs+lactmed:@term+@DOCNO+335. Accessed May 3, 2017.

21. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

22. Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):682-685.

23. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952-1960.

24. Bolton JM, Morin SN, Majumdar SR, et al. Association of mental disorders and related medication use with risk for major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):641-648.

25. Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, et al. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(1):61-70.

26. Lagnaoui R, Tournier M, Moride Y, et al. The risk of cognitive impairment in older community-dwelling women after benzodiazepine use. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):226-228.

27. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6231.

28. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

29. Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. No end in sight: benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2546-2553.

30. Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. National trends in antidepressant, benzodiazepine, and other sedative-hypnotic treatment of older adults in psychiatric and primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e363-e371.

31. Rapoport MJ, Lanctôt KL, Streiner DL, et al. Benzodiazepine use and driving: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):663-673.

32. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

33. Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Phillips GS, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of mortality among patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(5):661-667.

34. McCall WV, Benca RM, Rosenguist PB, et al. Hypnotic medications and suicide: risk, mechanisms, mitigation, and the FDA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(1):18-25.

35. Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688.

36. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Updated September 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

37. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(1):1-49.

38. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518697.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

39. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm518473.htm. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Controlled drugs: safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2427186353. Published April 2016. Accessed July 25, 2017.

41. Stahl SM. Anxiety disorders and anxiolytics. In: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008:721-772.

42. Paquin AM, Zimmerman K, Rudolph JL. Risk versus risk: a review of benzodiazepine reduction in older adults. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(7):919-934.

43. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valença AM, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(3):290-293.

44. Tampi R. How to wean geriatric patients off benzodiazepines. Psychiatric News. http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.PP3b6. Published March 18, 2016. Accessed May 3, 2017.