User login

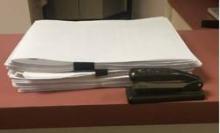

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.