User login

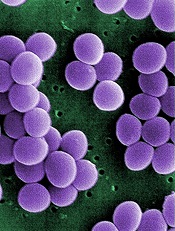

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()

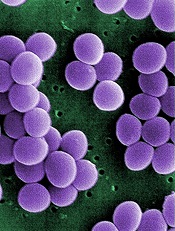

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()

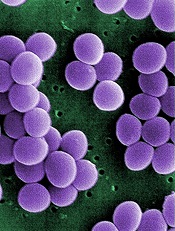

Credit: Janice Haney Carr

An analysis of 9 community hospitals showed that 1 in 3 patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate therapy.

The study also revealed growing resistance to treatment and a high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria in these hospitals.

Investigators said the findings, published in PLOS ONE, provide the most comprehensive look at bloodstream infections in community hospitals to date.

Much of the existing research on bloodstream infections focuses on tertiary care centers.

“Our study provides a much-needed update on what we’re seeing in community hospitals, and ultimately, we’re finding similar types of infections in these hospitals as in tertiary care centers,” said study author Deverick Anderson, MD, of Duke University in Durham North Carolina.

“It’s a challenge to identify bloodstream infections and treat them quickly and appropriately, but this study shows that there is room for improvement in both kinds of hospital settings.”

Types of infection

To better understand the types of bloodstream infections found in community hospitals, Dr Anderson and his colleagues collected information on patients treated at these hospitals in Virginia and North Carolina from 2003 to 2006.

The investigators focused on 1470 patients diagnosed with bloodstream infections. The infections were classified depending on where and when they were contracted.

Infections resulting from prior hospitalization, surgery, invasive devices (such as catheters), or living in long-term care facilities were designated healthcare-associated infections.

Community-acquired infections were contracted outside of medical settings or shortly after being admitted to a hospital. And hospital-onset infections occurred after being in a hospital for several days.

The investigators found that 56% of bloodstream infections were healthcare-associated, but symptoms began prior to hospital admission. Community-acquired infections unrelated to medical care were seen in 29% of patients. And 15% had hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections.

S aureus was the most common pathogen, causing 28% of bloodstream infections. This was closely followed by Escherichia coli, which was found in 24% of patients.

Bloodstream infections due to multidrug-resistant pathogens occurred in 23% of patients—an increase over earlier studies. And methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) was the most common multidrug-resistant pathogen.

“Similar patterns of pathogens and drug resistance have been observed in tertiary care centers, suggesting that bloodstream infections in community hospitals aren’t that different from tertiary care centers,” Dr Anderson said.

“There’s a misconception that community hospitals don’t have to deal with S aureus and MRSA, but our findings dispel that myth, since community hospitals also see these serious infections.”

Inappropriate therapy

The investigators also found that approximately 38% of patients with bloodstream infections received inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy or were not initially prescribed an effective antibiotic while the cause of the infection was still unknown.

A multivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with receiving inappropriate therapy, including the hospital where the patient received care (P<0.001), the need for assistance with 3 or more “daily living” activities (P=0.005), and a high Charlson score (P=0.05).

Community-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.01) and hospital-onset healthcare-associated infections (P=0.02) were associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy, when community-acquired infections were used as the reference.

The investigators also incorporated drug resistance into their analysis. And they found that infection due to a multidrug-resistant organism was strongly associated with the failure to receive appropriate therapy (P<0.0001).

But most of the predictors the team initially identified retained their significance. The patient’s hospital (P<0.001), need for assistance with activities (P=0.02), and type of infection remained significant (P=0.04), but the Charlson score did not (P=0.07).

Dr Anderson recommended that clinicians in community hospitals focus on these risk factors when choosing antibiotic therapy for patients with bloodstream infections. He noted that most risk factors for receiving inappropriate therapy are already recorded in electronic health records.

“Developing an intervention where electronic records automatically alert clinicians to these risk factors when they’re choosing antibiotics could help reduce the problem,” he said. “This is just a place to start, but it’s an example of an area where we could improve how we treat patients with bloodstream infections.” ![]()