User login

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a psychotic mood disorder. Like schizophrenia, it has been shown to be associated with significant degeneration and structural brain abnormalities with multiple relapses.1,2

Just as I have always advocated preventing recurrences in schizophrenia by using long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first episode to prevent psychotic relapses and progressive brain damage,3 I strongly recommend using LAIs right after hospital discharge from the first manic episode. It is the most rational management approach for bipolar mania given the grave consequences of multiple episodes, which are so common in this psychotic mood disorder due to poor medication adherence.

In contrast to the depressive episodes of BD I, where patients have insight into their depression and seek psychiatric treatment, during a manic episode patients often have no insight (anosognosia) that they suffer from a serious brain disorder, and refuse treatment.4 In addition, young patients with BD I frequently discontinue their oral mood stabilizer or second-generation antipsychotic (which are approved for mania) because they miss the blissful euphoria and the buoyant physical and mental energy of their manic episodes. They are completely oblivious to (and uninformed about) the grave neurobiological damage of further manic episodes, which can condemn them to clinical, functional, and cognitive deterioration. These patients are also likely to become treatment-resistant, which has been labeled as “the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder.”5

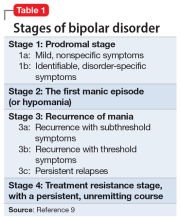

The evidence for progressive brain tissue loss, clinical deterioration, functional decline, and treatment resistance is abundant.6 I was the lead investigator of the first study to report ventricular dilatation (which is a proxy for cortical atrophy) in bipolar mania,7 a discovery that was subsequently replicated by 2 dozen researchers. This was followed by numerous neuroimaging studies reporting a loss of volume across multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia. BD is heterogeneous8 with 4 stages (Table 19), and patients experience progressively worse brain structure and function with each stage.

Many patients with bipolar mania end up with poor clinical and functional outcomes, even when they respond well to initial treatment with lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, or second-generation antipsychotics. With their intentional nonadherence to oral medications leading to multiple recurrent relapses, these patients are at serious risk for neuroprogression and brain atrophic changes driven by multiple factors: inflammatory cytokines, increased cortical steroids, decreased neurotrophins, deceased neurogenesis, increased oxidative stress, and mitochondrial energy dysfunction. The consequences include progressive shortening of the interval between episodes with every relapse and loss of responsiveness to pharmacotherapy as the illness progresses.6,10 Predictors of a downhill progression include genetic vulnerability, perinatal complication during fetal life, childhood trauma (physical, sexual, emotional, or neglect), substance use, stress, psychiatric/medial comorbidities, and especially the number of episodes.9,11

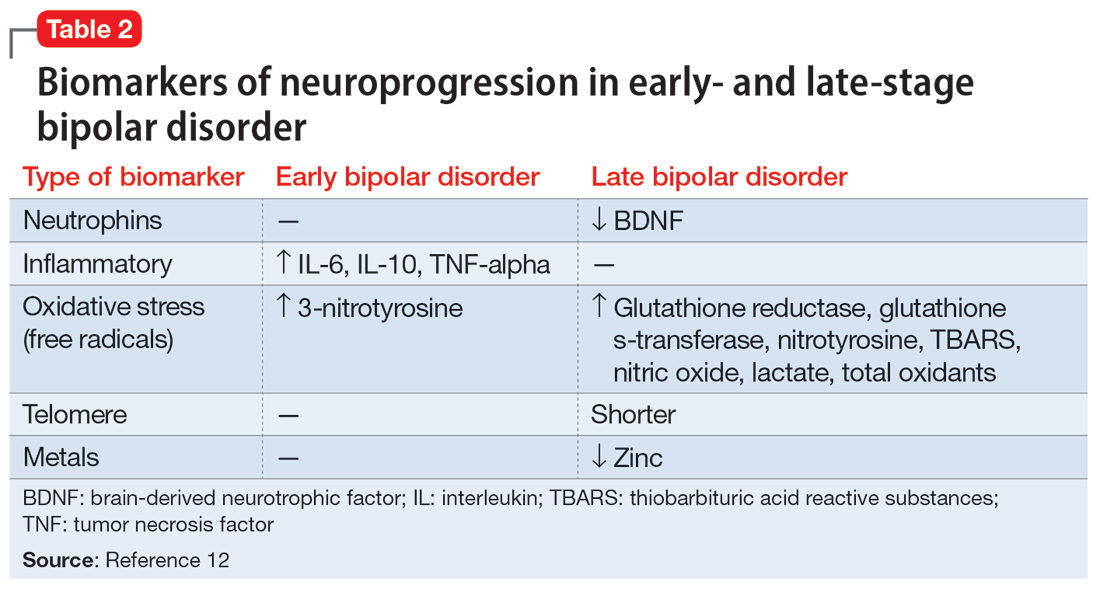

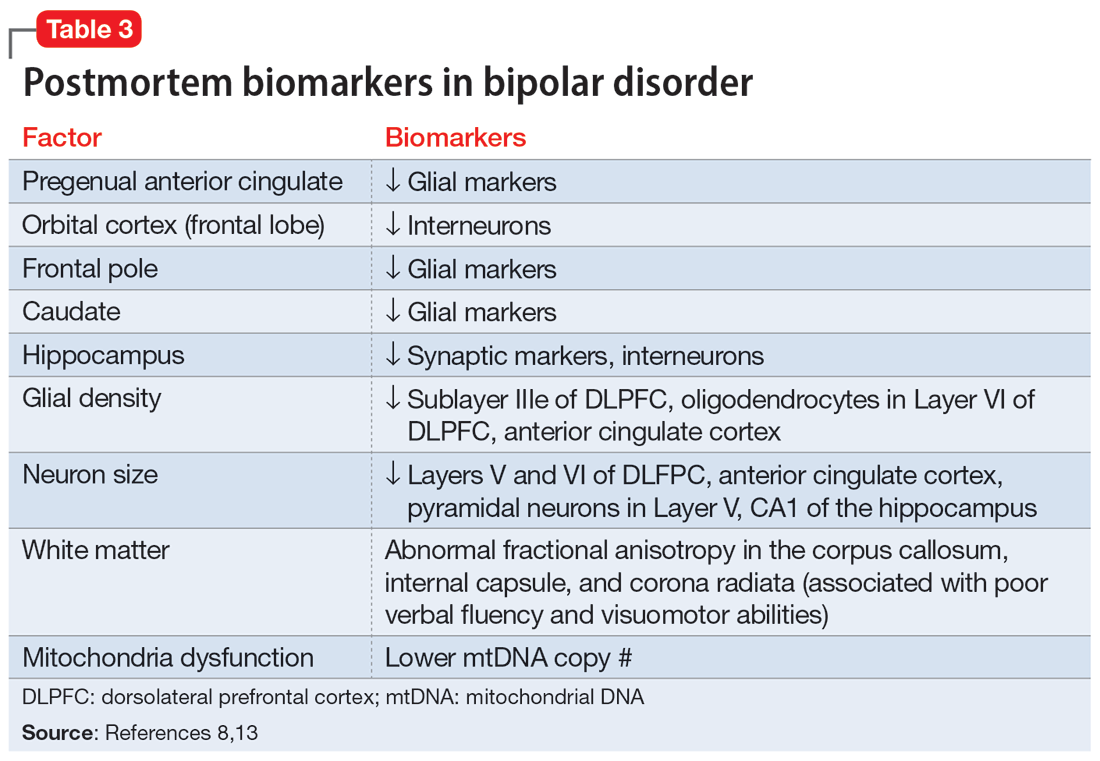

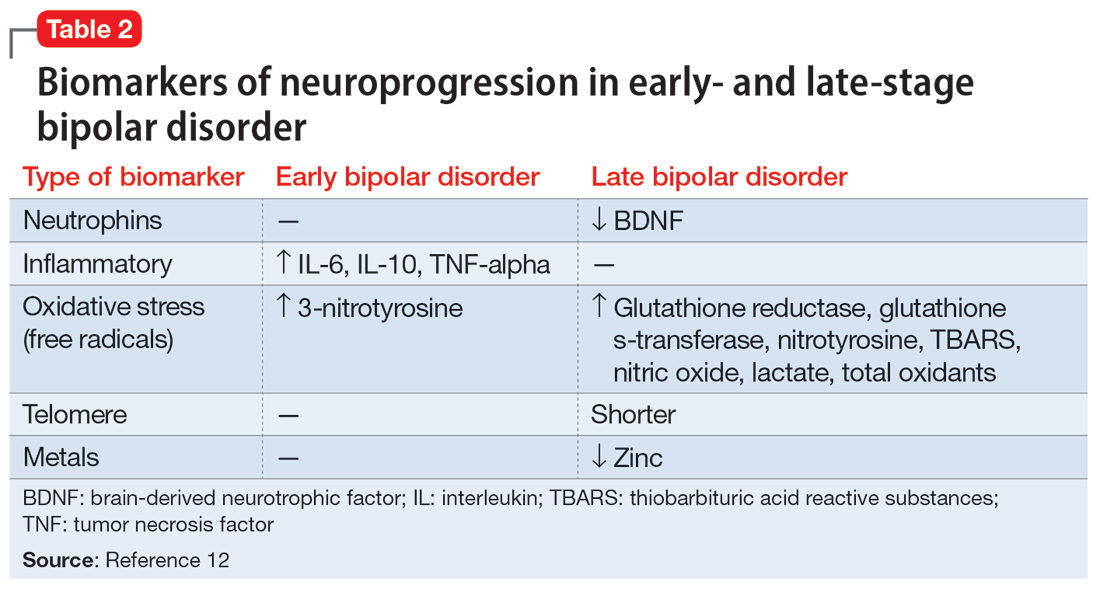

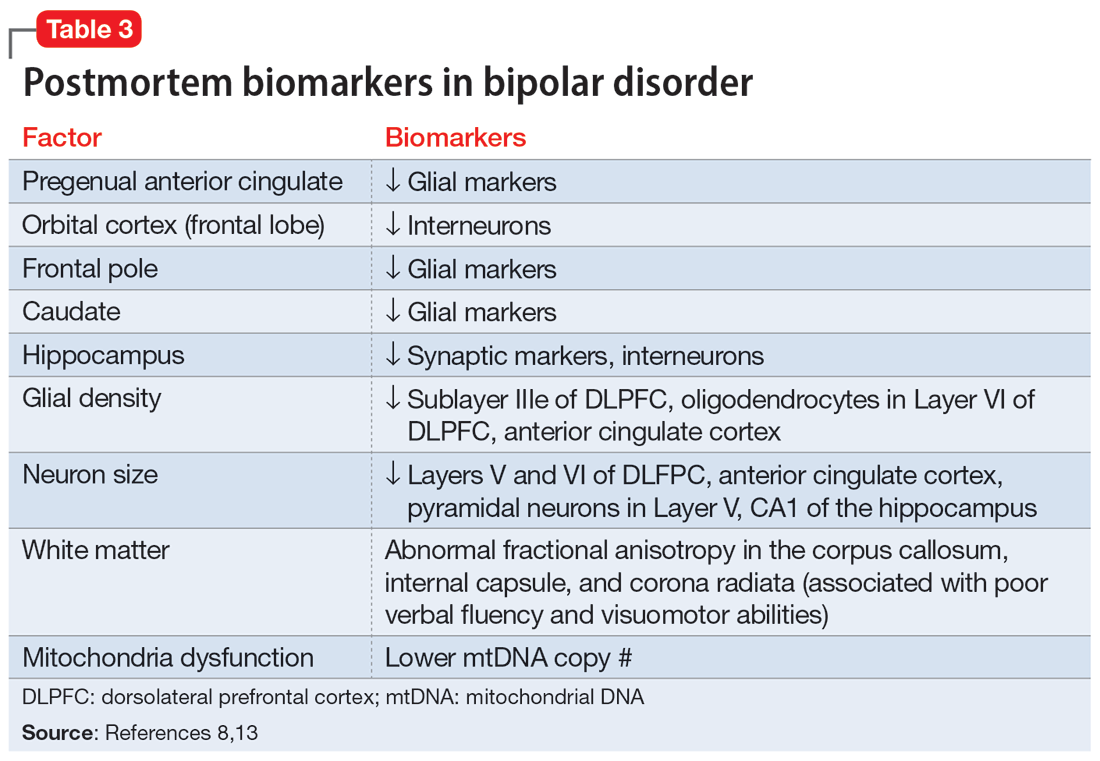

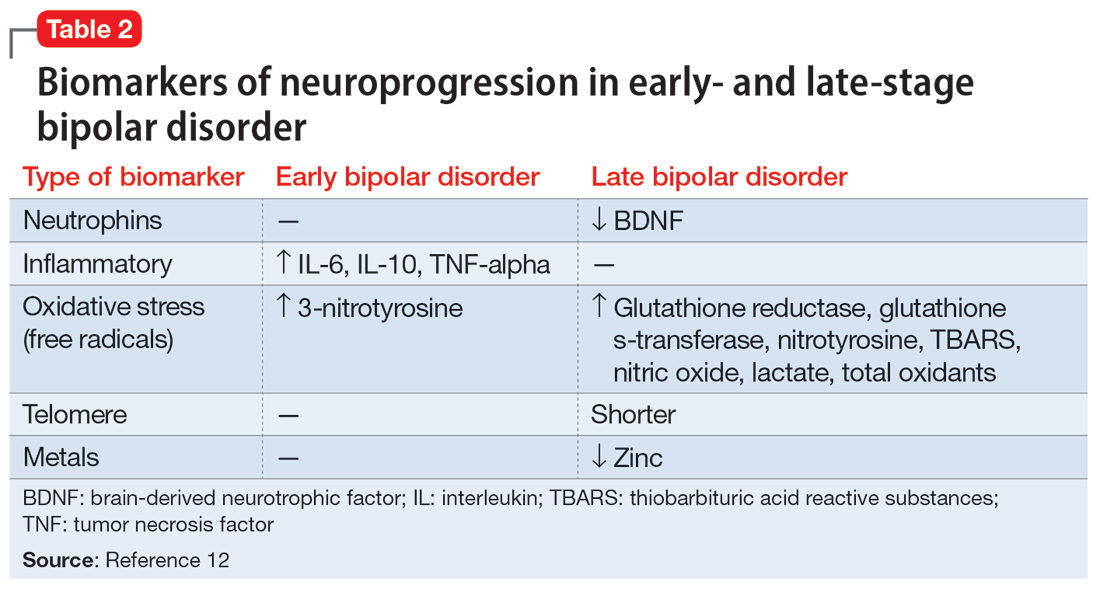

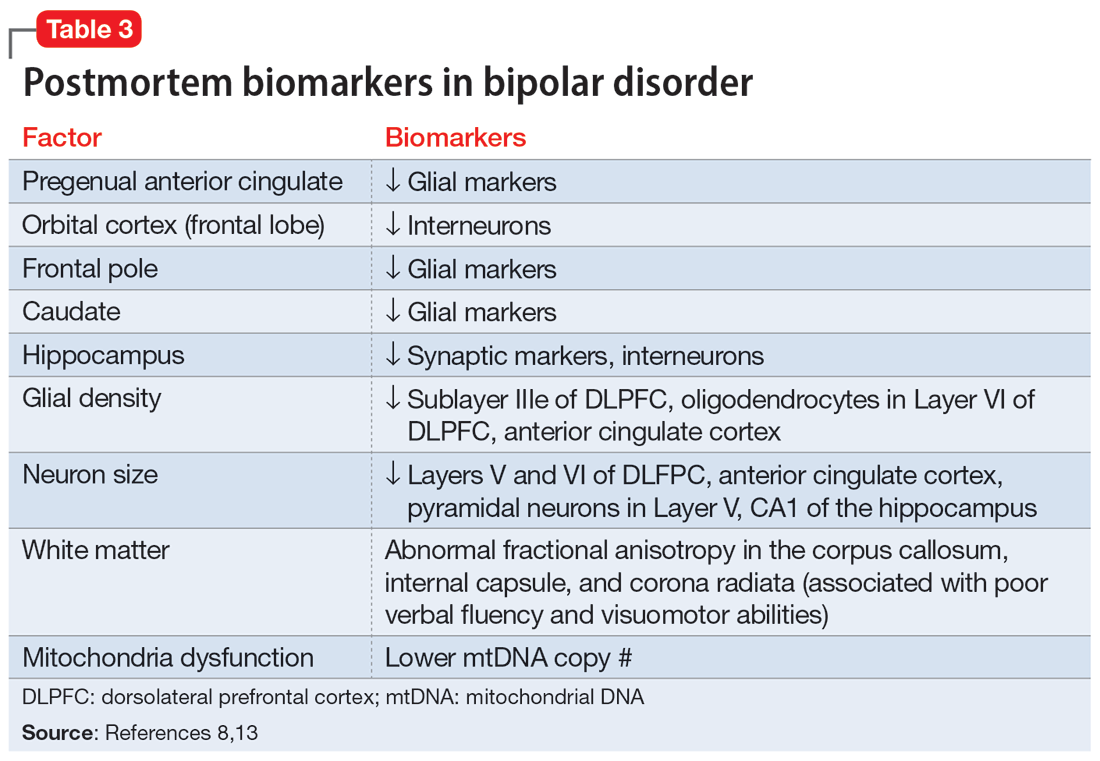

Biomarkers have been reported in both the early and late stages of BD (Table 212) as well as in postmortem studies (Table 38,13). They reflect the progressive neurodegenerative nature of recurrent BD I episodes as the disorder moves to the advanced stages. I summarize these stages in Table 19 and Table 212 for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who do not have access to the neuroscience journals where such findings are usually published.

BD I is also believed to be associated with accelerated aging14,15 and an increased risk for dementia16 or cognitive deterioration.17 There is also an emerging hypothesis that neuroprogression and treatment resistance in BD is frequently associated with insulin resistance,18 peripheral inflammation,19 and blood-brain barrier permeability dysfunction.20

The bottom line is that like patients with schizophrenia, where relapses lead to devastating consequences,21 those with BD are at a similar high risk for neuroprogression, which includes atrophy in several brain regions, treatment resistance, and functional disability. This underscores the urgency for implementing LAI therapy early in the illness, when the first manic episode (Stage 2) emerges after the prodrome (Stage 1). This is the best strategy to preserve brain health in persons with BD22 and to allow them to remain functional with their many intellectual gifts, such as eloquence, poetry, artistic talents, humor, and social skills. It is unfortunate that the combination of patients’ and clinicians’ reluctance to use an LAI early in the illness dooms many patients with BD to a potentially avoidable malignant outcome.

1. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(1):105-106.

2. Kapezinski NS, Mwangi B, Cassidy RM, et al. Neuroprogression and illness trajectories in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(3):277-285.

3. Nasrallah HA. Errors of omission and commission in psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(11):4,6,8.

4. Nasrallah HA. Is anosognosia a delusion, a negative symptom, or a cognitive deficit? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):6-8,14.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

6. Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804-817.

7. Nasrallah HA, McCalley-Whitters M, Jacoby CG. Cerebral ventricular enlargement in young manic males. A controlled CT study. J Affective Dis. 1982;4(1):15-19.

8. Maletic V, Raison C. Integrated neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:98.

9. Berk M. Neuroprogression: pathways to progressive brain changes in bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):441-445.

10. Berk M, Conus P, Kapczinski F, et al. From neuroprogression to neuroprotection: implications for clinical care. Med J Aust. 2010;193(S4):S36-S40.

11. Passos IC, Mwangi B, Vieta E, et al. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(2):91-103.

12. Fries GR, Pfaffenseller B, Stertz L, et al. Staging and neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):667-675.

13. Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):541-547.

14. Fries GR, Zamzow MJ, Andrews T, et al. Accelerated aging in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review of molecular findings and their clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:107-116.

15. Fries GR, Bauer IE, Scaini G, et al. Accelerated hippocampal biological aging in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis. 2020;22(5):498-507.

16. Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Cao F, et al. History of bipolar disorder and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(4):357-362.

17. Bauer IE, Ouyang A, Mwangi B, et al. Reduced white matter integrity and verbal fluency impairment in young adults with bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:115-122.

18. Calkin CV. Insulin resistance takes center stage: a new paradigm in the progression of bipolar disorder. Ann Med. 2019;51(5-6):281-293.

19. Grewal S, McKinlay S, Kapczinski F, et al. Biomarkers of neuroprogression and late staging in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(3):328-343.

20. Calkin C, McClelland C, Cairns K, et al. Insulin resistance and blood-brain barrier dysfunction underlie neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:636174.

21. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

22. Berk M, Hallam K, Malhi GS, et al. Evidence and implications for early intervention in bipolar disorder. J Ment Health. 2010;19(2):113-126.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a psychotic mood disorder. Like schizophrenia, it has been shown to be associated with significant degeneration and structural brain abnormalities with multiple relapses.1,2

Just as I have always advocated preventing recurrences in schizophrenia by using long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first episode to prevent psychotic relapses and progressive brain damage,3 I strongly recommend using LAIs right after hospital discharge from the first manic episode. It is the most rational management approach for bipolar mania given the grave consequences of multiple episodes, which are so common in this psychotic mood disorder due to poor medication adherence.

In contrast to the depressive episodes of BD I, where patients have insight into their depression and seek psychiatric treatment, during a manic episode patients often have no insight (anosognosia) that they suffer from a serious brain disorder, and refuse treatment.4 In addition, young patients with BD I frequently discontinue their oral mood stabilizer or second-generation antipsychotic (which are approved for mania) because they miss the blissful euphoria and the buoyant physical and mental energy of their manic episodes. They are completely oblivious to (and uninformed about) the grave neurobiological damage of further manic episodes, which can condemn them to clinical, functional, and cognitive deterioration. These patients are also likely to become treatment-resistant, which has been labeled as “the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder.”5

The evidence for progressive brain tissue loss, clinical deterioration, functional decline, and treatment resistance is abundant.6 I was the lead investigator of the first study to report ventricular dilatation (which is a proxy for cortical atrophy) in bipolar mania,7 a discovery that was subsequently replicated by 2 dozen researchers. This was followed by numerous neuroimaging studies reporting a loss of volume across multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia. BD is heterogeneous8 with 4 stages (Table 19), and patients experience progressively worse brain structure and function with each stage.

Many patients with bipolar mania end up with poor clinical and functional outcomes, even when they respond well to initial treatment with lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, or second-generation antipsychotics. With their intentional nonadherence to oral medications leading to multiple recurrent relapses, these patients are at serious risk for neuroprogression and brain atrophic changes driven by multiple factors: inflammatory cytokines, increased cortical steroids, decreased neurotrophins, deceased neurogenesis, increased oxidative stress, and mitochondrial energy dysfunction. The consequences include progressive shortening of the interval between episodes with every relapse and loss of responsiveness to pharmacotherapy as the illness progresses.6,10 Predictors of a downhill progression include genetic vulnerability, perinatal complication during fetal life, childhood trauma (physical, sexual, emotional, or neglect), substance use, stress, psychiatric/medial comorbidities, and especially the number of episodes.9,11

Biomarkers have been reported in both the early and late stages of BD (Table 212) as well as in postmortem studies (Table 38,13). They reflect the progressive neurodegenerative nature of recurrent BD I episodes as the disorder moves to the advanced stages. I summarize these stages in Table 19 and Table 212 for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who do not have access to the neuroscience journals where such findings are usually published.

BD I is also believed to be associated with accelerated aging14,15 and an increased risk for dementia16 or cognitive deterioration.17 There is also an emerging hypothesis that neuroprogression and treatment resistance in BD is frequently associated with insulin resistance,18 peripheral inflammation,19 and blood-brain barrier permeability dysfunction.20

The bottom line is that like patients with schizophrenia, where relapses lead to devastating consequences,21 those with BD are at a similar high risk for neuroprogression, which includes atrophy in several brain regions, treatment resistance, and functional disability. This underscores the urgency for implementing LAI therapy early in the illness, when the first manic episode (Stage 2) emerges after the prodrome (Stage 1). This is the best strategy to preserve brain health in persons with BD22 and to allow them to remain functional with their many intellectual gifts, such as eloquence, poetry, artistic talents, humor, and social skills. It is unfortunate that the combination of patients’ and clinicians’ reluctance to use an LAI early in the illness dooms many patients with BD to a potentially avoidable malignant outcome.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a psychotic mood disorder. Like schizophrenia, it has been shown to be associated with significant degeneration and structural brain abnormalities with multiple relapses.1,2

Just as I have always advocated preventing recurrences in schizophrenia by using long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first episode to prevent psychotic relapses and progressive brain damage,3 I strongly recommend using LAIs right after hospital discharge from the first manic episode. It is the most rational management approach for bipolar mania given the grave consequences of multiple episodes, which are so common in this psychotic mood disorder due to poor medication adherence.

In contrast to the depressive episodes of BD I, where patients have insight into their depression and seek psychiatric treatment, during a manic episode patients often have no insight (anosognosia) that they suffer from a serious brain disorder, and refuse treatment.4 In addition, young patients with BD I frequently discontinue their oral mood stabilizer or second-generation antipsychotic (which are approved for mania) because they miss the blissful euphoria and the buoyant physical and mental energy of their manic episodes. They are completely oblivious to (and uninformed about) the grave neurobiological damage of further manic episodes, which can condemn them to clinical, functional, and cognitive deterioration. These patients are also likely to become treatment-resistant, which has been labeled as “the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder.”5

The evidence for progressive brain tissue loss, clinical deterioration, functional decline, and treatment resistance is abundant.6 I was the lead investigator of the first study to report ventricular dilatation (which is a proxy for cortical atrophy) in bipolar mania,7 a discovery that was subsequently replicated by 2 dozen researchers. This was followed by numerous neuroimaging studies reporting a loss of volume across multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia. BD is heterogeneous8 with 4 stages (Table 19), and patients experience progressively worse brain structure and function with each stage.

Many patients with bipolar mania end up with poor clinical and functional outcomes, even when they respond well to initial treatment with lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, or second-generation antipsychotics. With their intentional nonadherence to oral medications leading to multiple recurrent relapses, these patients are at serious risk for neuroprogression and brain atrophic changes driven by multiple factors: inflammatory cytokines, increased cortical steroids, decreased neurotrophins, deceased neurogenesis, increased oxidative stress, and mitochondrial energy dysfunction. The consequences include progressive shortening of the interval between episodes with every relapse and loss of responsiveness to pharmacotherapy as the illness progresses.6,10 Predictors of a downhill progression include genetic vulnerability, perinatal complication during fetal life, childhood trauma (physical, sexual, emotional, or neglect), substance use, stress, psychiatric/medial comorbidities, and especially the number of episodes.9,11

Biomarkers have been reported in both the early and late stages of BD (Table 212) as well as in postmortem studies (Table 38,13). They reflect the progressive neurodegenerative nature of recurrent BD I episodes as the disorder moves to the advanced stages. I summarize these stages in Table 19 and Table 212 for the benefit of psychiatric clinicians who do not have access to the neuroscience journals where such findings are usually published.

BD I is also believed to be associated with accelerated aging14,15 and an increased risk for dementia16 or cognitive deterioration.17 There is also an emerging hypothesis that neuroprogression and treatment resistance in BD is frequently associated with insulin resistance,18 peripheral inflammation,19 and blood-brain barrier permeability dysfunction.20

The bottom line is that like patients with schizophrenia, where relapses lead to devastating consequences,21 those with BD are at a similar high risk for neuroprogression, which includes atrophy in several brain regions, treatment resistance, and functional disability. This underscores the urgency for implementing LAI therapy early in the illness, when the first manic episode (Stage 2) emerges after the prodrome (Stage 1). This is the best strategy to preserve brain health in persons with BD22 and to allow them to remain functional with their many intellectual gifts, such as eloquence, poetry, artistic talents, humor, and social skills. It is unfortunate that the combination of patients’ and clinicians’ reluctance to use an LAI early in the illness dooms many patients with BD to a potentially avoidable malignant outcome.

1. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(1):105-106.

2. Kapezinski NS, Mwangi B, Cassidy RM, et al. Neuroprogression and illness trajectories in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(3):277-285.

3. Nasrallah HA. Errors of omission and commission in psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(11):4,6,8.

4. Nasrallah HA. Is anosognosia a delusion, a negative symptom, or a cognitive deficit? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):6-8,14.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

6. Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804-817.

7. Nasrallah HA, McCalley-Whitters M, Jacoby CG. Cerebral ventricular enlargement in young manic males. A controlled CT study. J Affective Dis. 1982;4(1):15-19.

8. Maletic V, Raison C. Integrated neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:98.

9. Berk M. Neuroprogression: pathways to progressive brain changes in bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):441-445.

10. Berk M, Conus P, Kapczinski F, et al. From neuroprogression to neuroprotection: implications for clinical care. Med J Aust. 2010;193(S4):S36-S40.

11. Passos IC, Mwangi B, Vieta E, et al. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(2):91-103.

12. Fries GR, Pfaffenseller B, Stertz L, et al. Staging and neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):667-675.

13. Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):541-547.

14. Fries GR, Zamzow MJ, Andrews T, et al. Accelerated aging in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review of molecular findings and their clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:107-116.

15. Fries GR, Bauer IE, Scaini G, et al. Accelerated hippocampal biological aging in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis. 2020;22(5):498-507.

16. Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Cao F, et al. History of bipolar disorder and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(4):357-362.

17. Bauer IE, Ouyang A, Mwangi B, et al. Reduced white matter integrity and verbal fluency impairment in young adults with bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:115-122.

18. Calkin CV. Insulin resistance takes center stage: a new paradigm in the progression of bipolar disorder. Ann Med. 2019;51(5-6):281-293.

19. Grewal S, McKinlay S, Kapczinski F, et al. Biomarkers of neuroprogression and late staging in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(3):328-343.

20. Calkin C, McClelland C, Cairns K, et al. Insulin resistance and blood-brain barrier dysfunction underlie neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:636174.

21. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

22. Berk M, Hallam K, Malhi GS, et al. Evidence and implications for early intervention in bipolar disorder. J Ment Health. 2010;19(2):113-126.

1. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Adler CM. The functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder: a review of neuroimaging findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(1):105-106.

2. Kapezinski NS, Mwangi B, Cassidy RM, et al. Neuroprogression and illness trajectories in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(3):277-285.

3. Nasrallah HA. Errors of omission and commission in psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(11):4,6,8.

4. Nasrallah HA. Is anosognosia a delusion, a negative symptom, or a cognitive deficit? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):6-8,14.

5. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198.

6. Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804-817.

7. Nasrallah HA, McCalley-Whitters M, Jacoby CG. Cerebral ventricular enlargement in young manic males. A controlled CT study. J Affective Dis. 1982;4(1):15-19.

8. Maletic V, Raison C. Integrated neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:98.

9. Berk M. Neuroprogression: pathways to progressive brain changes in bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):441-445.

10. Berk M, Conus P, Kapczinski F, et al. From neuroprogression to neuroprotection: implications for clinical care. Med J Aust. 2010;193(S4):S36-S40.

11. Passos IC, Mwangi B, Vieta E, et al. Areas of controversy in neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(2):91-103.

12. Fries GR, Pfaffenseller B, Stertz L, et al. Staging and neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):667-675.

13. Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):541-547.

14. Fries GR, Zamzow MJ, Andrews T, et al. Accelerated aging in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review of molecular findings and their clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:107-116.

15. Fries GR, Bauer IE, Scaini G, et al. Accelerated hippocampal biological aging in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Dis. 2020;22(5):498-507.

16. Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Cao F, et al. History of bipolar disorder and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(4):357-362.

17. Bauer IE, Ouyang A, Mwangi B, et al. Reduced white matter integrity and verbal fluency impairment in young adults with bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;62:115-122.

18. Calkin CV. Insulin resistance takes center stage: a new paradigm in the progression of bipolar disorder. Ann Med. 2019;51(5-6):281-293.

19. Grewal S, McKinlay S, Kapczinski F, et al. Biomarkers of neuroprogression and late staging in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(3):328-343.

20. Calkin C, McClelland C, Cairns K, et al. Insulin resistance and blood-brain barrier dysfunction underlie neuroprogression in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:636174.

21. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

22. Berk M, Hallam K, Malhi GS, et al. Evidence and implications for early intervention in bipolar disorder. J Ment Health. 2010;19(2):113-126.