User login

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

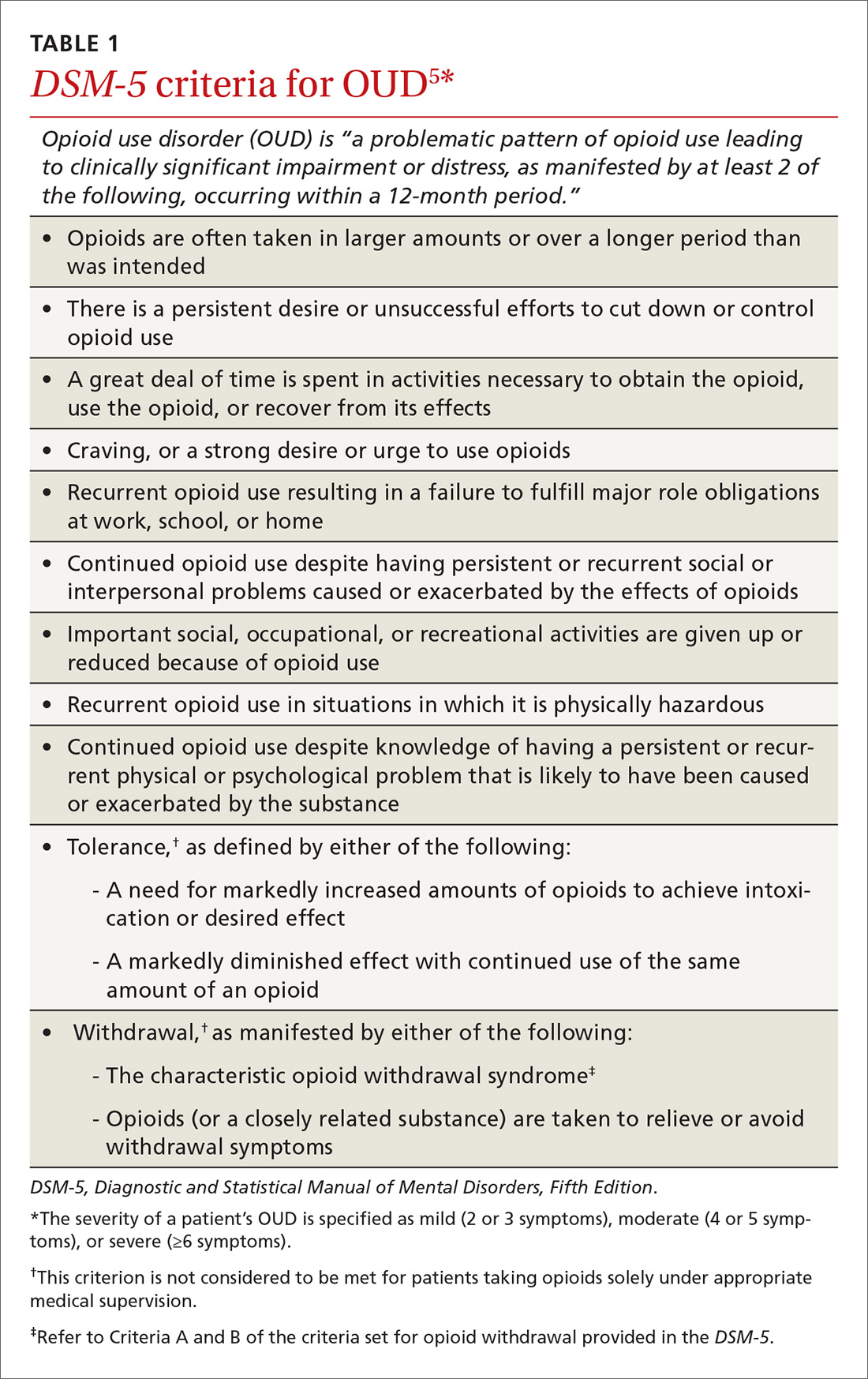

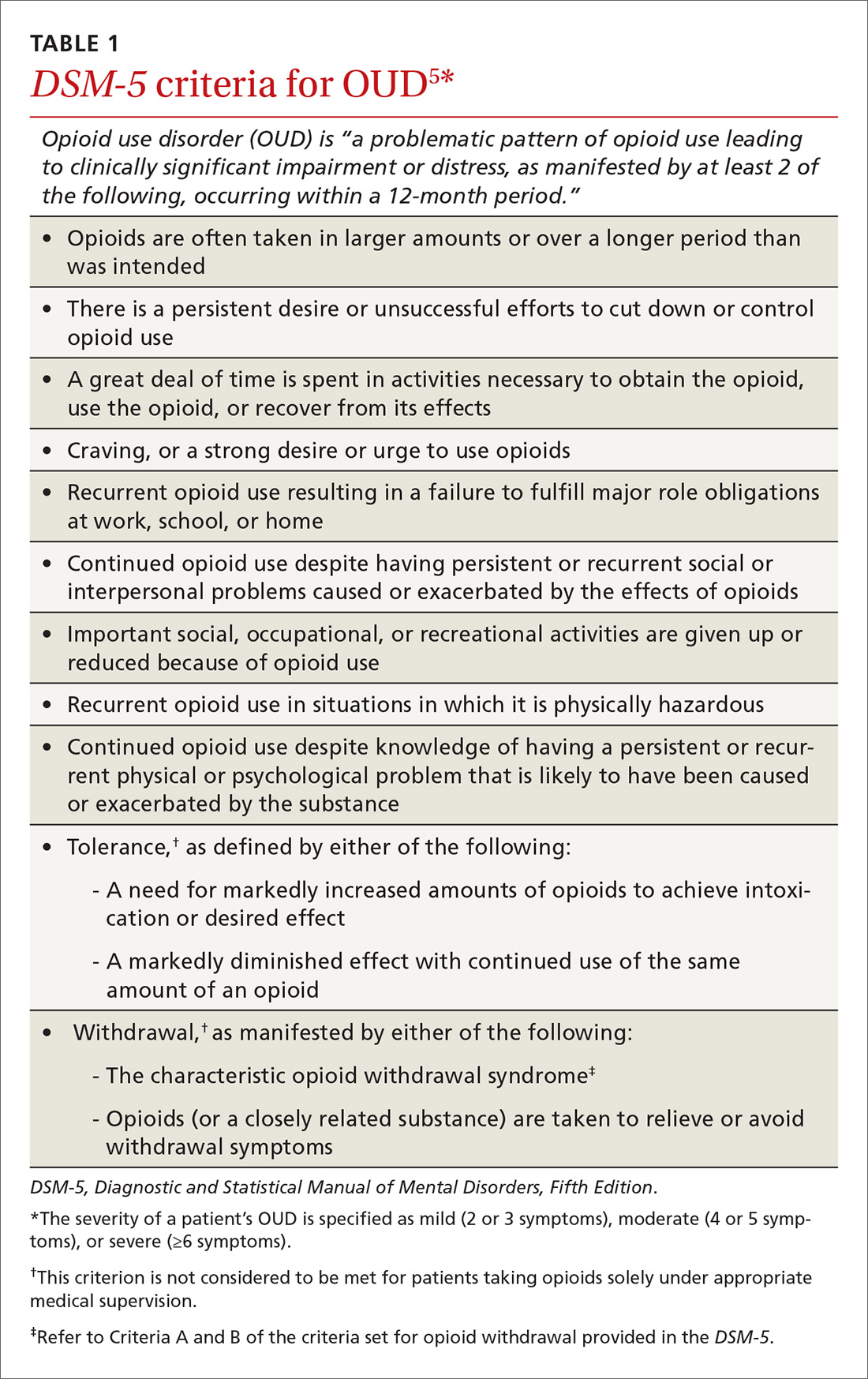

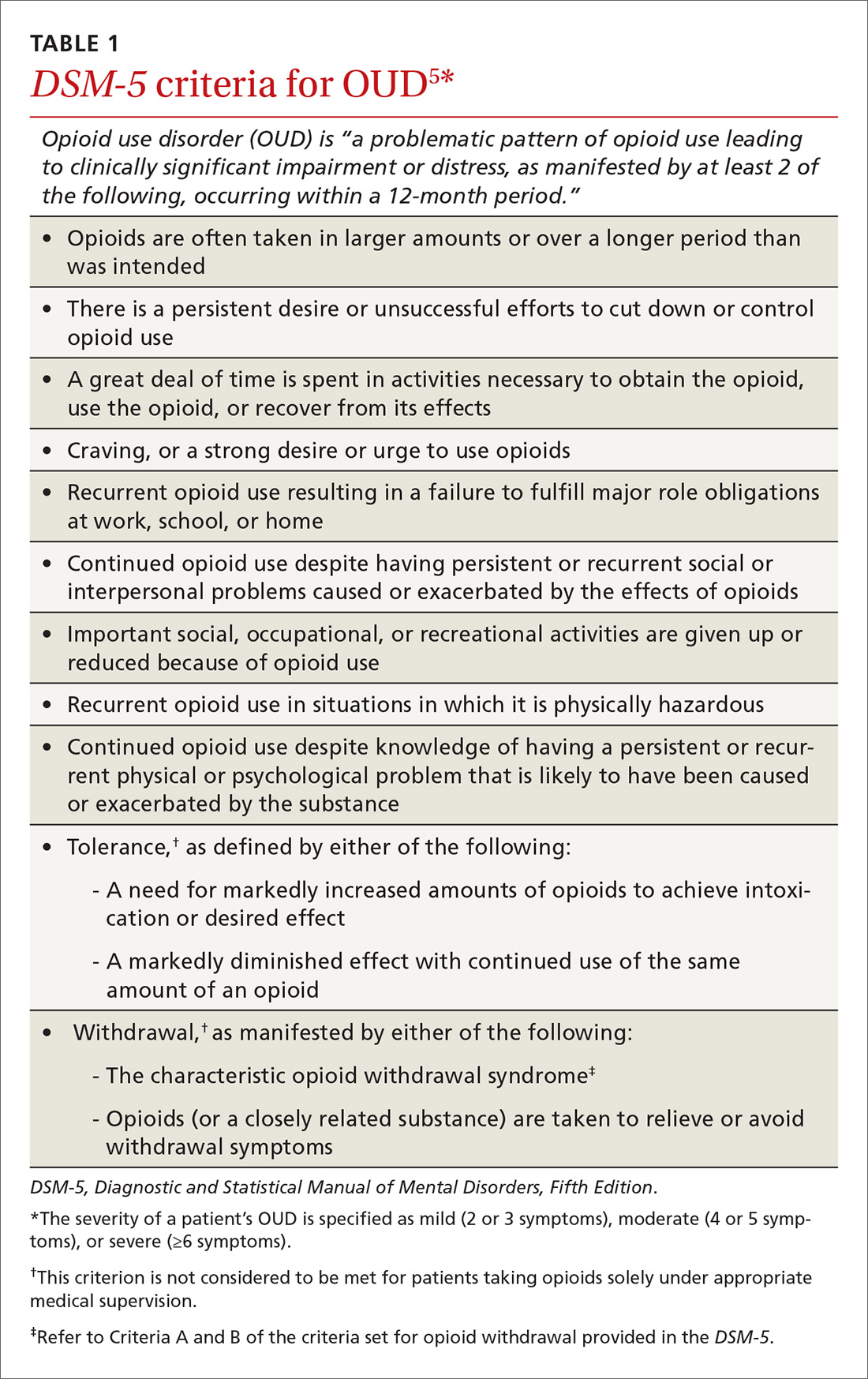

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

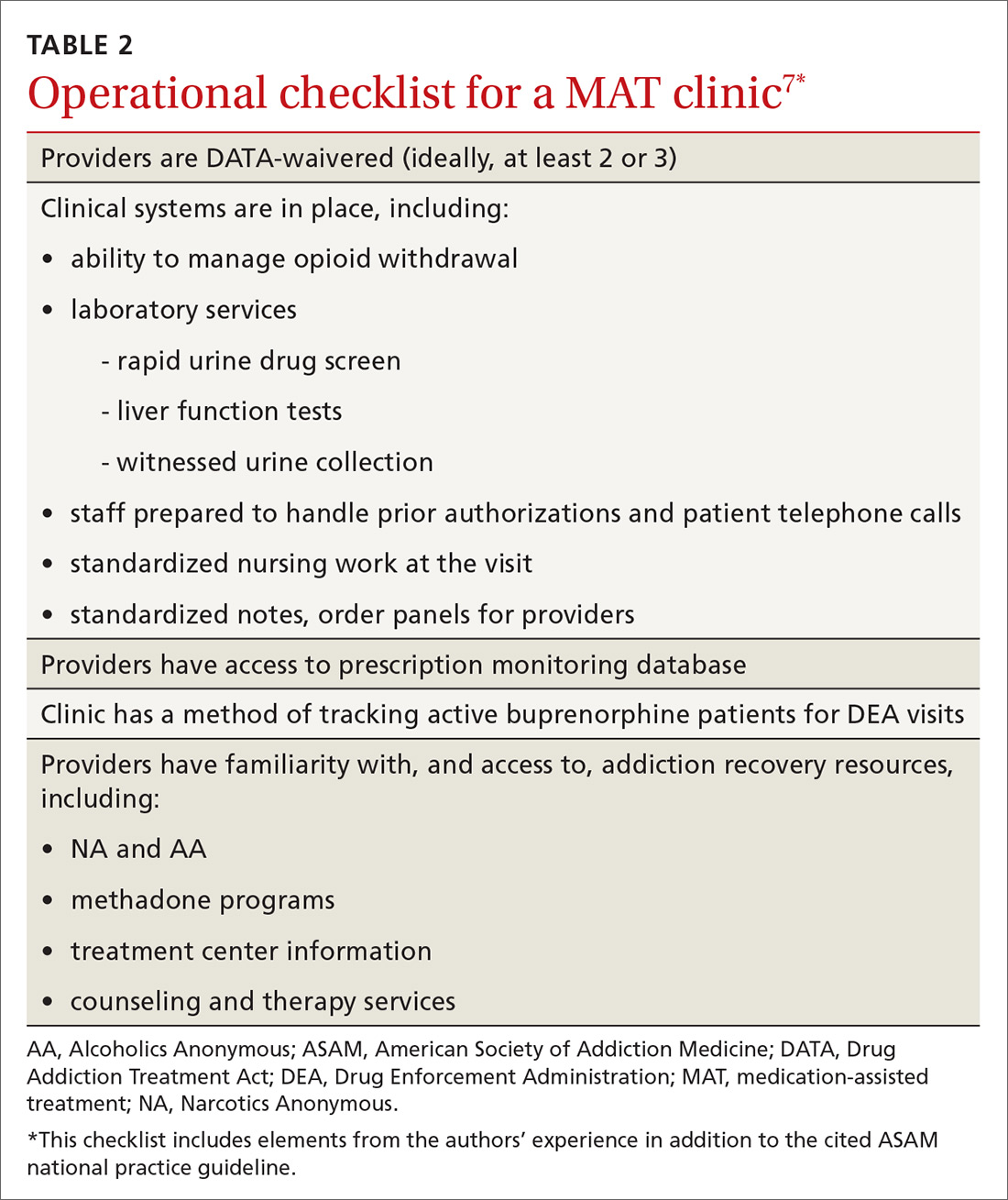

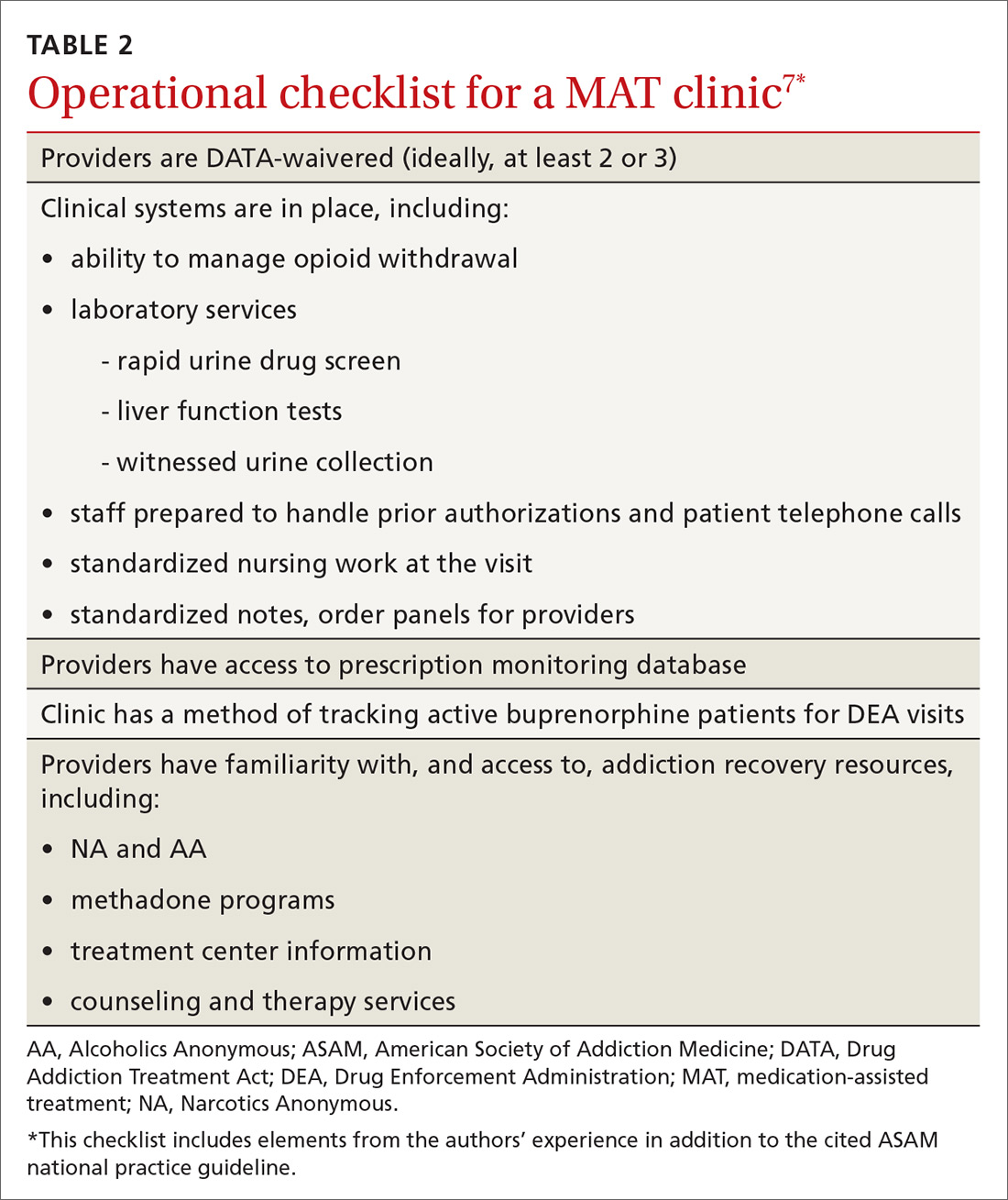

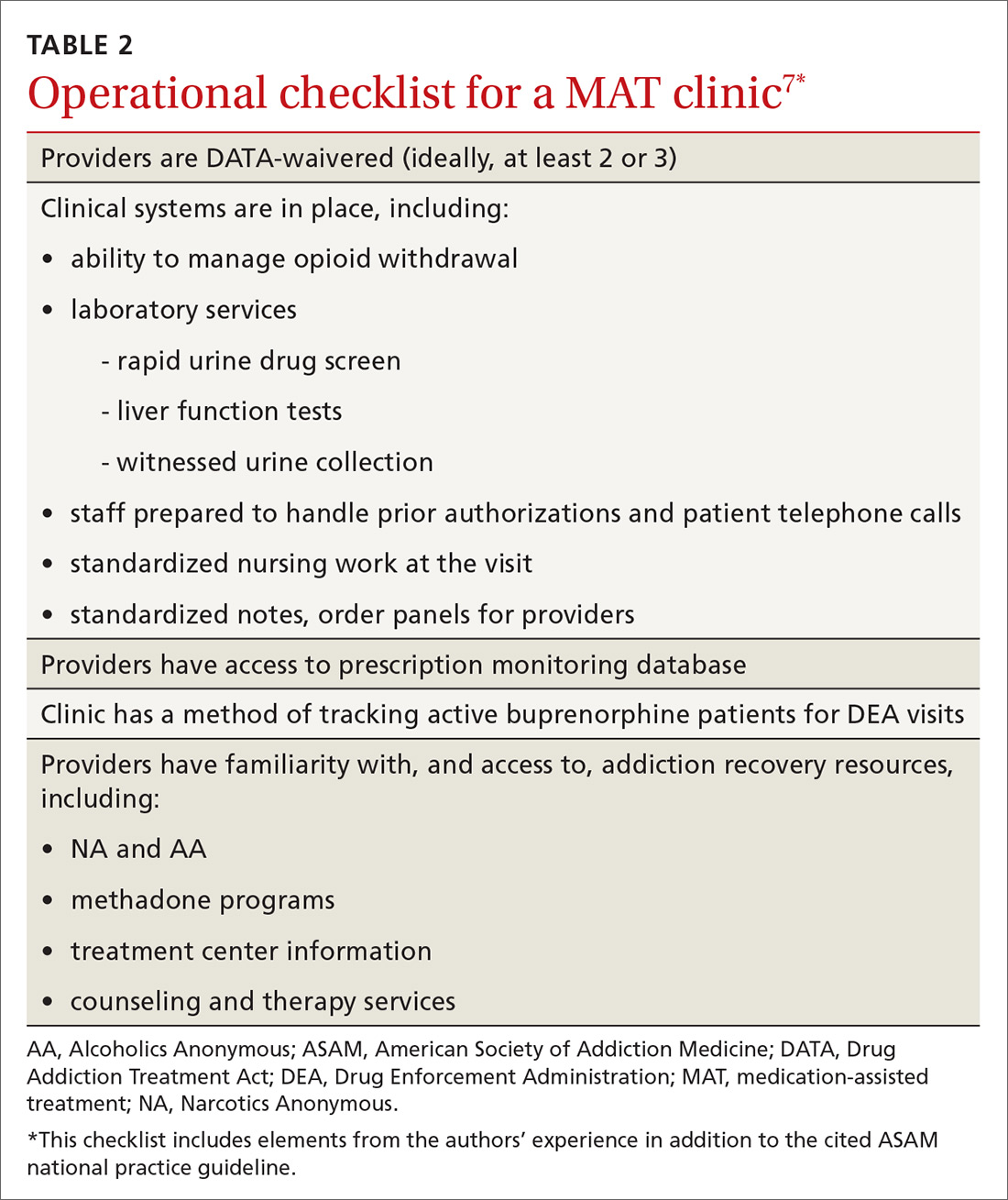

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected].

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use signs of intoxication, signs of withdrawal, urine drug screening, and diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, to screen for, and diagnose, opioid use disorder. C

› Offer and institute medication-assisted treatment when appropriate to reduce the risk of opioid-related and overall mortality in patients with opioid use disorder. A

› Identify and treat comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with opioid use disorder, which provides benefit during treatment of the disorder. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series