User login

› Prescribe low-dose diuretics and recommend sodium restriction for patients with cirrhosis who have grade 2 (moderate) ascites. C

› Initiate treatment with beta-blockers to prevent variceal bleeding in all patients with medium or large varices, as well as in those with small varices who also have red wale signs and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis. A

› Consider evaluation for liver transplantation for a patient with cirrhosis who has experienced a major complication (eg, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or variceal hemorrhage) or one who has a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score ≥15. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 59, seeks care at the local emergency department (ED) for shortness of breath. He also complains that his abdomen has been getting “bigger and bigger.” The ED physician recognizes that he is suffering from cirrhosis with secondary ascites and admits him. A paracentesis is performed and 7 L of fluid are removed. The patient is started on furosemide 40 mg/d and the health care team educates him about the relationship between his alcohol consumption and his enlarging abdomen. At discharge, he is told to follow up with his primary care physician.

Two weeks later, the patient arrives at your clinic for followup. What is the next step in managing this patient?

Cirrhosis—the end stage of chronic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis—is a relatively common and often fatal diagnosis. In the United States, an estimated 633,000 adults have cirrhosis,1 and each year approximately 32,000 people die from the condition.2 The most common causes of cirrhosis are heavy alcohol use, chronic hepatitis B or C infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.3 Cirrhosis typically involves degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, which are replaced by fibrotic tissues and regenerative nodules, leading to loss of liver function.4

Patients with cirrhosis can be treated as outpatients—that is, until they decompensate. Obviously, treatment specific to the underlying causes of cirrhosis, such as interferon for a patient with hepatitis and abstinence for a patient with alcohol-related liver disease, should be the first concern. However, this article focuses on the family physician’s role in identifying and treating several of the most common complications of cirrhosis, including ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. We will also cover which patients should be referred for evaluation for liver transplantation. (For a guide to providing patient education for individuals with cirrhosis, see “Dx cirrhosis: What to teach your patient”.3,5-10)

Sodium restriction, diuretics are first steps for ascites

The goals of ascites treatment are to prevent or relieve dyspnea and abdominal pain and to prevent life-threatening complications, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and hepatorenal syndrome.11 Patient education is key regarding weight gain; that’s why it’s important to instruct patients to contact you if they gain more than 2 lbs/d for 3 consecutive days or more than 10 lbs.12

Approximately 10% of patients with ascites respond well to sodium restriction alone (1500-2000 mg/d).11 In addition to sodium restriction, patients with grade 2 ascites (moderate ascites with proportionate abdominal distension) should receive a low-dose diuretic, such as spironolactone (initial dose, 50-100 mg/d; increase up to 200-300 mg/d)13 or amiloride (5-10 mg/d).5

Painful gynecomastia and hyperkalemia are the most common adverse effects of spironolactone.13 Amiloride has fewer adverse effects than spironolactone, but is less effective.11 Low-dose furosemide (20-40 mg/d) may be added, although weight loss should be monitored to watch for excessive diuresis, which can lead to renal failure, hyponatremia, or encephalopathy.5,13 Also monitor electrolytes to watch for hypokalemia or hyponatremia.13

Recommended weight loss to prevent renal failure is 300 to 500 g/d (.66-1.1 lbs/d) for patients without peripheral edema, and 800 to 1000 g/d (1.7-2.2 lbs/d) for patients with peripheral edema.5,13

Patients with grade 3 (tense) or refractory ascites should have large-volume paracentesis (LVP) plus an albumin infusion.5 LVP (removal of >5 L of fluid) is more effective, faster, and has less risk of adverse effects than increasing the dosage of the patient’s diuretic.5,13 LVP can be done in an outpatient setting and is considered safe—even for patients with a prolonged prothrombin time.13,14 Rare complications of LVP include significant bleeding at the puncture site, infection, and intestinal perforation.5

Diuretics should be prescribed after LVP to prevent ascites recurrence.5 Plasma expanders can prevent hepatorenal syndrome, ascites recurrence, and dilutional hyponatremia.5,11 Albumin is the most efficacious of these agents;5,14 it is administered intravenously at a dose of 8 to 10 g/L of fluid removed.13,15

Take steps to prevent variceal bleeding

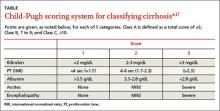

Soon after a patient is diagnosed with cirrhosis, he or she should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to screen for the presence and size of varices.16 Although they can’t prevent esophagogastric varices, nonselective beta-blockers (NSBBs) are the gold standard for preventing first variceal hemorrhage in patients with small varices with red wale signs on the varices and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis (TABLE17), and in all patients with medium or large varices.18 Propranolol is usually started at 20 mg BID, or nadolol is started at 20 to 40 mg/d.16 The NSBB dose is adjusted to the maximum tolerated dose, which occurs when the patient's heart rate is reduced to 55 to 60 beats/min.

NSBBs are associated with poor survival in patients with refractory ascites and thus are contraindicated in these patients.19 NSBBs also should not be taken by patients with SBP because use of these medications is associated with worse outcomes compared to those not receiving NSBBs.20

Endoscopic variceal ligation is an alternative to NSBBs for the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage in patients with medium to large varices.18 In particular, ligation should be considered for patients with high-risk varices in whom beta-blockers are contraindicated or must be discontinued because of adverse effects.21

Avoid nitrates in patients with varices because these agents do not prevent first variceal hemorrhage and have been associated with higher mortality rates in patients older than 50.16 There is no significant additional benefit or mortality reduction associated with adding a nitrate to an NSBB.22 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or surgically created shunts are reserved for patients for whom medical therapy fails.18

Mental status changes suggest hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a reversible impairment of neuropsychiatric function that is associated with impaired hepatic function. Because a patient with encephalopathy presents with an altered mental status, he or she may need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment.

The goals of hepatic encephalopathy treatment are to identify and correct precipitating causes and lower serum ammonia concentrations to improve mental status.15 Nutritional support should be provided without protein restriction unless the patient is severely proteinintolerant.23 The recommended initial therapy is lactulose 30 to 45 mL 2 to 4 times per day, to decrease absorption of ammonia in the gut. The dose should be titrated until patients have 2 to 3 soft stools daily.24

For patients who can’t tolerate lactulose or whose mental status doesn’t improve within 48 hours, rifaximin 400 mg orally 3 times daily or 550 mg 2 times daily is recommended.25 Neomycin 500 mg orally 3 times a day or 1 g twice daily is a second-line agent reserved for patients who are unable to take rifaximin; however, its efficacy is not well established, and neomycin has been associated with ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.24

Watch for signs of kidney failure

Hepatorenal syndrome is renal failure induced by severe hepatic injury and characterized by azotemia and decreased renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate.15 It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Hepatorenal syndrome is typically caused by arterial vasodilation in the splanchnic circulation in patients with portal hypertension.15,26,27 Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by at least a 2-fold increase in serum creatinine to a level of >2.5 mg/dL over more than 2 weeks. Patients typically have urine output <400 to 500 mL/d. Type 2 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by less severe renal impairment; it is associated with ascites that does not improve with diuretics.28

Patients with hepatorenal syndrome should not use any nephrotoxic agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Inpatient treatment is usually required and may include norepinephrine with albumin, terlipressin with midodrine, or octreotide and albumin. Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy may benefit from TIPS as a bridge until they can undergo liver transplantation.29

When to consider liver transplantation

The appropriateness and timing of liver transplantation should be determined on a case-by-case basis. For some patients with cirrhosis, transplantation may be the definitive treatment. For example, in some patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation is an option because transplantation can cure the tumor and underlying cirrhosis. However, while transplantation is a suitable option for early HCC in patients with cirrhosis, it has been shown to have limited efficacy in patients with advanced disease who are not selected using specific criteria.30

Referral for evaluation for transplantation should be considered once a patient with cirrhosis experiences a major complication (eg, ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy).31 Another criterion for timing and allocation of liver transplantation is based on the statistical model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), which is used to predict 3-month survival in patients with cirrhosis based on the relationships between serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and international normalized ratio values.15 Liver transplantation should be considered for patients with a MELD score ≥15.15,31 Such patients should be promptly referred to a liver transplantation specialist to allow sufficient time for the appropriate psychosocial assessments and medical evaluations, and for patients and their families to receive appropriate education on things like the risks and benefits of transplantation.15

Patients with cirrhosis should be educated about complications of their condition, including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).5 It’s important to explain that they will need to be evaluated every 6 months with serology and ultrasound to assess disease changes.6 Annual screening for HCC should be done with ultrasound or computed tomography scanning with or without alpha-fetoprotein.6

Ensure that your patient knows that he needs to receive the recommended immunizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients with cirrhosis should receive annual influenza, pneumococcal 23, and hepatitis A and B series vaccinations.7

Advise patients with cirrhosis to be cautious when taking any medications. Patients with cirrhosis should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because these medications encourage sodium retention, which can exacerbate ascites.6 Acetaminophen use is discouraged, but should not be harmful unless the patient takes >2 g/d.8

Emphasize the importance of eating a healthy diet. Malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis3 and correlates with more severe disease and poorer outcomes, including mortality.9 Nutritional recommendations for patients with alcohol-related liver disease include thiamine 50 mg orally or intramuscularly, and riboflavin and pyridoxine in the recommended daily doses.10 Advise patients to take other vitamins, as needed, to treat any deficiencies.9

CASE › After evaluating Mr. M, you prescribe spironolactone 100 mg/d and furosemide 40 mg twice a day to address ascites, and propranolol—which you titrate to 80 mg twice a day—to prevent variceal hemorrhage. Mr. M is maintained on these medications and returns with his daughter, as he has been doing every 2 to 3 months. He is excited that he breathes easily as long as he avoids salt and takes his medications. He continues to see his hepatologist regularly, and his last paracentesis was 4 months ago. He has not used any alcohol since he was taught about the relationship between alcohol and his breathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suzanne Minor, MD, FAAF P, Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Humanities, Health, & Society, Florida International University, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC II, 554A, Miami, FL 33199; [email protected]

1. Scaglion S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: A population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014. October 8. [Epub ahead of print.]

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2015.

3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Cirrhosis. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Web site. Available at: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/liver-disease/cirrhosis/Pages/facts.aspx. Accessed April 30, 2015.

4. Zhou WC, Zhang QB, Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7312-7324.

5. Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:1646-1654.

6. Grattagliano I, Ubaldi E, Bonfrate L, et al. Management of liver cirrhosis between primary care and specialists. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2273-2282.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 recommended immunizations for adults: By age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule-easyread.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2015.

8. Bacon BR. Cirrhosis and its complications. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. Available from: http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79748841. Accessed April 28, 2015.

9. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:14-32.

10. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert. Alcoholic liver disease. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2005. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa64/aa64.htm. Accessed April 18, 2015.

11. Kashani A, Landaverde C, Medici V, et al. Fluid retention in cirrhosis: pathophysiology and management. QJM. 2008;101:71-85.

12. Chalasani NP, Vuppalanchi RK. Ascites: A common problem in people with cirrhosis. July 2013. American College of Gastroenterology Web site. Available at: http://patients.gi.org/topics/ascites/. Accessed April 28, 2015.

13. Kuiper JJ, van Buuren HR, de Man RA. Ascites in cirrhosis: a review of management and complications. Neth J Med. 2007;65:283-288.

14. Biecker E. Diagnosis and therapy of ascites in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroentol. 2011;17:1237-1248.

15. Heidelbaugh JJ, Sherbondy M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: Part II. Complications and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:767-776.

16. Garcia-Tsao G, Lim JK; Members of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program. Management and treatment of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1802-1829.

17. Infante-Rivard C, Esnaola S, Villeneuve JP. Clinical and statistical validity of conventional prognostic factors in predicting shortterm survival among cirrhotics. Hepatology. 1987;7:660-664.

18. Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, et al; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938.

19. Serste T, Melot C, Francoz C, et al. Deleterious effects of betablockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010;52:1017-1022.

20. Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective b blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1680–1690.e1.

21. Sarin SK, Lamba GS, Kumar M, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:988-993.

22. Garcia-Pagan JC, Feu F, Bosch J, et al. Propranolol compared with propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. A randomized controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:869-873.

23. Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325-336.

24. Sharma P, Sharma BC. Disaccharides in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:313-320.

25. Jiang Q, Jiang XH, Zheng MH, et al. Rifaximin versus nonabsorbable disaccharides in the management of hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1064-1070.

26. Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1279-1290.

27. Iwakiri Y. The molecules: mechanisms of arterial vasodilatation observed in the splanchnic and systemic circulation in portal hypertension. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(Suppl 3):S288-S294.

28. Epstein M, Berk DP, Hollenberg NK, et al. Renal failure in the patient with cirrhosis. The role of active vasoconstriction. Am J Med. 1970;49:175-185.

29. Singh V, Ghosh S, Singh B, et al. Noradrenaline vs. terlipressin in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1293-1298.

30. Chua TC, Saxena A, Chu F, et al. Hepatic resection for transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma for patients within Milan and UCSF criteria. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:141-145.

31. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144-1165.

› Prescribe low-dose diuretics and recommend sodium restriction for patients with cirrhosis who have grade 2 (moderate) ascites. C

› Initiate treatment with beta-blockers to prevent variceal bleeding in all patients with medium or large varices, as well as in those with small varices who also have red wale signs and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis. A

› Consider evaluation for liver transplantation for a patient with cirrhosis who has experienced a major complication (eg, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or variceal hemorrhage) or one who has a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score ≥15. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 59, seeks care at the local emergency department (ED) for shortness of breath. He also complains that his abdomen has been getting “bigger and bigger.” The ED physician recognizes that he is suffering from cirrhosis with secondary ascites and admits him. A paracentesis is performed and 7 L of fluid are removed. The patient is started on furosemide 40 mg/d and the health care team educates him about the relationship between his alcohol consumption and his enlarging abdomen. At discharge, he is told to follow up with his primary care physician.

Two weeks later, the patient arrives at your clinic for followup. What is the next step in managing this patient?

Cirrhosis—the end stage of chronic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis—is a relatively common and often fatal diagnosis. In the United States, an estimated 633,000 adults have cirrhosis,1 and each year approximately 32,000 people die from the condition.2 The most common causes of cirrhosis are heavy alcohol use, chronic hepatitis B or C infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.3 Cirrhosis typically involves degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, which are replaced by fibrotic tissues and regenerative nodules, leading to loss of liver function.4

Patients with cirrhosis can be treated as outpatients—that is, until they decompensate. Obviously, treatment specific to the underlying causes of cirrhosis, such as interferon for a patient with hepatitis and abstinence for a patient with alcohol-related liver disease, should be the first concern. However, this article focuses on the family physician’s role in identifying and treating several of the most common complications of cirrhosis, including ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. We will also cover which patients should be referred for evaluation for liver transplantation. (For a guide to providing patient education for individuals with cirrhosis, see “Dx cirrhosis: What to teach your patient”.3,5-10)

Sodium restriction, diuretics are first steps for ascites

The goals of ascites treatment are to prevent or relieve dyspnea and abdominal pain and to prevent life-threatening complications, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and hepatorenal syndrome.11 Patient education is key regarding weight gain; that’s why it’s important to instruct patients to contact you if they gain more than 2 lbs/d for 3 consecutive days or more than 10 lbs.12

Approximately 10% of patients with ascites respond well to sodium restriction alone (1500-2000 mg/d).11 In addition to sodium restriction, patients with grade 2 ascites (moderate ascites with proportionate abdominal distension) should receive a low-dose diuretic, such as spironolactone (initial dose, 50-100 mg/d; increase up to 200-300 mg/d)13 or amiloride (5-10 mg/d).5

Painful gynecomastia and hyperkalemia are the most common adverse effects of spironolactone.13 Amiloride has fewer adverse effects than spironolactone, but is less effective.11 Low-dose furosemide (20-40 mg/d) may be added, although weight loss should be monitored to watch for excessive diuresis, which can lead to renal failure, hyponatremia, or encephalopathy.5,13 Also monitor electrolytes to watch for hypokalemia or hyponatremia.13

Recommended weight loss to prevent renal failure is 300 to 500 g/d (.66-1.1 lbs/d) for patients without peripheral edema, and 800 to 1000 g/d (1.7-2.2 lbs/d) for patients with peripheral edema.5,13

Patients with grade 3 (tense) or refractory ascites should have large-volume paracentesis (LVP) plus an albumin infusion.5 LVP (removal of >5 L of fluid) is more effective, faster, and has less risk of adverse effects than increasing the dosage of the patient’s diuretic.5,13 LVP can be done in an outpatient setting and is considered safe—even for patients with a prolonged prothrombin time.13,14 Rare complications of LVP include significant bleeding at the puncture site, infection, and intestinal perforation.5

Diuretics should be prescribed after LVP to prevent ascites recurrence.5 Plasma expanders can prevent hepatorenal syndrome, ascites recurrence, and dilutional hyponatremia.5,11 Albumin is the most efficacious of these agents;5,14 it is administered intravenously at a dose of 8 to 10 g/L of fluid removed.13,15

Take steps to prevent variceal bleeding

Soon after a patient is diagnosed with cirrhosis, he or she should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to screen for the presence and size of varices.16 Although they can’t prevent esophagogastric varices, nonselective beta-blockers (NSBBs) are the gold standard for preventing first variceal hemorrhage in patients with small varices with red wale signs on the varices and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis (TABLE17), and in all patients with medium or large varices.18 Propranolol is usually started at 20 mg BID, or nadolol is started at 20 to 40 mg/d.16 The NSBB dose is adjusted to the maximum tolerated dose, which occurs when the patient's heart rate is reduced to 55 to 60 beats/min.

NSBBs are associated with poor survival in patients with refractory ascites and thus are contraindicated in these patients.19 NSBBs also should not be taken by patients with SBP because use of these medications is associated with worse outcomes compared to those not receiving NSBBs.20

Endoscopic variceal ligation is an alternative to NSBBs for the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage in patients with medium to large varices.18 In particular, ligation should be considered for patients with high-risk varices in whom beta-blockers are contraindicated or must be discontinued because of adverse effects.21

Avoid nitrates in patients with varices because these agents do not prevent first variceal hemorrhage and have been associated with higher mortality rates in patients older than 50.16 There is no significant additional benefit or mortality reduction associated with adding a nitrate to an NSBB.22 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or surgically created shunts are reserved for patients for whom medical therapy fails.18

Mental status changes suggest hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a reversible impairment of neuropsychiatric function that is associated with impaired hepatic function. Because a patient with encephalopathy presents with an altered mental status, he or she may need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment.

The goals of hepatic encephalopathy treatment are to identify and correct precipitating causes and lower serum ammonia concentrations to improve mental status.15 Nutritional support should be provided without protein restriction unless the patient is severely proteinintolerant.23 The recommended initial therapy is lactulose 30 to 45 mL 2 to 4 times per day, to decrease absorption of ammonia in the gut. The dose should be titrated until patients have 2 to 3 soft stools daily.24

For patients who can’t tolerate lactulose or whose mental status doesn’t improve within 48 hours, rifaximin 400 mg orally 3 times daily or 550 mg 2 times daily is recommended.25 Neomycin 500 mg orally 3 times a day or 1 g twice daily is a second-line agent reserved for patients who are unable to take rifaximin; however, its efficacy is not well established, and neomycin has been associated with ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.24

Watch for signs of kidney failure

Hepatorenal syndrome is renal failure induced by severe hepatic injury and characterized by azotemia and decreased renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate.15 It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Hepatorenal syndrome is typically caused by arterial vasodilation in the splanchnic circulation in patients with portal hypertension.15,26,27 Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by at least a 2-fold increase in serum creatinine to a level of >2.5 mg/dL over more than 2 weeks. Patients typically have urine output <400 to 500 mL/d. Type 2 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by less severe renal impairment; it is associated with ascites that does not improve with diuretics.28

Patients with hepatorenal syndrome should not use any nephrotoxic agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Inpatient treatment is usually required and may include norepinephrine with albumin, terlipressin with midodrine, or octreotide and albumin. Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy may benefit from TIPS as a bridge until they can undergo liver transplantation.29

When to consider liver transplantation

The appropriateness and timing of liver transplantation should be determined on a case-by-case basis. For some patients with cirrhosis, transplantation may be the definitive treatment. For example, in some patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation is an option because transplantation can cure the tumor and underlying cirrhosis. However, while transplantation is a suitable option for early HCC in patients with cirrhosis, it has been shown to have limited efficacy in patients with advanced disease who are not selected using specific criteria.30

Referral for evaluation for transplantation should be considered once a patient with cirrhosis experiences a major complication (eg, ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy).31 Another criterion for timing and allocation of liver transplantation is based on the statistical model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), which is used to predict 3-month survival in patients with cirrhosis based on the relationships between serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and international normalized ratio values.15 Liver transplantation should be considered for patients with a MELD score ≥15.15,31 Such patients should be promptly referred to a liver transplantation specialist to allow sufficient time for the appropriate psychosocial assessments and medical evaluations, and for patients and their families to receive appropriate education on things like the risks and benefits of transplantation.15

Patients with cirrhosis should be educated about complications of their condition, including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).5 It’s important to explain that they will need to be evaluated every 6 months with serology and ultrasound to assess disease changes.6 Annual screening for HCC should be done with ultrasound or computed tomography scanning with or without alpha-fetoprotein.6

Ensure that your patient knows that he needs to receive the recommended immunizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients with cirrhosis should receive annual influenza, pneumococcal 23, and hepatitis A and B series vaccinations.7

Advise patients with cirrhosis to be cautious when taking any medications. Patients with cirrhosis should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because these medications encourage sodium retention, which can exacerbate ascites.6 Acetaminophen use is discouraged, but should not be harmful unless the patient takes >2 g/d.8

Emphasize the importance of eating a healthy diet. Malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis3 and correlates with more severe disease and poorer outcomes, including mortality.9 Nutritional recommendations for patients with alcohol-related liver disease include thiamine 50 mg orally or intramuscularly, and riboflavin and pyridoxine in the recommended daily doses.10 Advise patients to take other vitamins, as needed, to treat any deficiencies.9

CASE › After evaluating Mr. M, you prescribe spironolactone 100 mg/d and furosemide 40 mg twice a day to address ascites, and propranolol—which you titrate to 80 mg twice a day—to prevent variceal hemorrhage. Mr. M is maintained on these medications and returns with his daughter, as he has been doing every 2 to 3 months. He is excited that he breathes easily as long as he avoids salt and takes his medications. He continues to see his hepatologist regularly, and his last paracentesis was 4 months ago. He has not used any alcohol since he was taught about the relationship between alcohol and his breathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suzanne Minor, MD, FAAF P, Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Humanities, Health, & Society, Florida International University, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC II, 554A, Miami, FL 33199; [email protected]

› Prescribe low-dose diuretics and recommend sodium restriction for patients with cirrhosis who have grade 2 (moderate) ascites. C

› Initiate treatment with beta-blockers to prevent variceal bleeding in all patients with medium or large varices, as well as in those with small varices who also have red wale signs and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis. A

› Consider evaluation for liver transplantation for a patient with cirrhosis who has experienced a major complication (eg, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or variceal hemorrhage) or one who has a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score ≥15. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 59, seeks care at the local emergency department (ED) for shortness of breath. He also complains that his abdomen has been getting “bigger and bigger.” The ED physician recognizes that he is suffering from cirrhosis with secondary ascites and admits him. A paracentesis is performed and 7 L of fluid are removed. The patient is started on furosemide 40 mg/d and the health care team educates him about the relationship between his alcohol consumption and his enlarging abdomen. At discharge, he is told to follow up with his primary care physician.

Two weeks later, the patient arrives at your clinic for followup. What is the next step in managing this patient?

Cirrhosis—the end stage of chronic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis—is a relatively common and often fatal diagnosis. In the United States, an estimated 633,000 adults have cirrhosis,1 and each year approximately 32,000 people die from the condition.2 The most common causes of cirrhosis are heavy alcohol use, chronic hepatitis B or C infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.3 Cirrhosis typically involves degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, which are replaced by fibrotic tissues and regenerative nodules, leading to loss of liver function.4

Patients with cirrhosis can be treated as outpatients—that is, until they decompensate. Obviously, treatment specific to the underlying causes of cirrhosis, such as interferon for a patient with hepatitis and abstinence for a patient with alcohol-related liver disease, should be the first concern. However, this article focuses on the family physician’s role in identifying and treating several of the most common complications of cirrhosis, including ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. We will also cover which patients should be referred for evaluation for liver transplantation. (For a guide to providing patient education for individuals with cirrhosis, see “Dx cirrhosis: What to teach your patient”.3,5-10)

Sodium restriction, diuretics are first steps for ascites

The goals of ascites treatment are to prevent or relieve dyspnea and abdominal pain and to prevent life-threatening complications, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and hepatorenal syndrome.11 Patient education is key regarding weight gain; that’s why it’s important to instruct patients to contact you if they gain more than 2 lbs/d for 3 consecutive days or more than 10 lbs.12

Approximately 10% of patients with ascites respond well to sodium restriction alone (1500-2000 mg/d).11 In addition to sodium restriction, patients with grade 2 ascites (moderate ascites with proportionate abdominal distension) should receive a low-dose diuretic, such as spironolactone (initial dose, 50-100 mg/d; increase up to 200-300 mg/d)13 or amiloride (5-10 mg/d).5

Painful gynecomastia and hyperkalemia are the most common adverse effects of spironolactone.13 Amiloride has fewer adverse effects than spironolactone, but is less effective.11 Low-dose furosemide (20-40 mg/d) may be added, although weight loss should be monitored to watch for excessive diuresis, which can lead to renal failure, hyponatremia, or encephalopathy.5,13 Also monitor electrolytes to watch for hypokalemia or hyponatremia.13

Recommended weight loss to prevent renal failure is 300 to 500 g/d (.66-1.1 lbs/d) for patients without peripheral edema, and 800 to 1000 g/d (1.7-2.2 lbs/d) for patients with peripheral edema.5,13

Patients with grade 3 (tense) or refractory ascites should have large-volume paracentesis (LVP) plus an albumin infusion.5 LVP (removal of >5 L of fluid) is more effective, faster, and has less risk of adverse effects than increasing the dosage of the patient’s diuretic.5,13 LVP can be done in an outpatient setting and is considered safe—even for patients with a prolonged prothrombin time.13,14 Rare complications of LVP include significant bleeding at the puncture site, infection, and intestinal perforation.5

Diuretics should be prescribed after LVP to prevent ascites recurrence.5 Plasma expanders can prevent hepatorenal syndrome, ascites recurrence, and dilutional hyponatremia.5,11 Albumin is the most efficacious of these agents;5,14 it is administered intravenously at a dose of 8 to 10 g/L of fluid removed.13,15

Take steps to prevent variceal bleeding

Soon after a patient is diagnosed with cirrhosis, he or she should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy to screen for the presence and size of varices.16 Although they can’t prevent esophagogastric varices, nonselective beta-blockers (NSBBs) are the gold standard for preventing first variceal hemorrhage in patients with small varices with red wale signs on the varices and/or Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis (TABLE17), and in all patients with medium or large varices.18 Propranolol is usually started at 20 mg BID, or nadolol is started at 20 to 40 mg/d.16 The NSBB dose is adjusted to the maximum tolerated dose, which occurs when the patient's heart rate is reduced to 55 to 60 beats/min.

NSBBs are associated with poor survival in patients with refractory ascites and thus are contraindicated in these patients.19 NSBBs also should not be taken by patients with SBP because use of these medications is associated with worse outcomes compared to those not receiving NSBBs.20

Endoscopic variceal ligation is an alternative to NSBBs for the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage in patients with medium to large varices.18 In particular, ligation should be considered for patients with high-risk varices in whom beta-blockers are contraindicated or must be discontinued because of adverse effects.21

Avoid nitrates in patients with varices because these agents do not prevent first variceal hemorrhage and have been associated with higher mortality rates in patients older than 50.16 There is no significant additional benefit or mortality reduction associated with adding a nitrate to an NSBB.22 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or surgically created shunts are reserved for patients for whom medical therapy fails.18

Mental status changes suggest hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a reversible impairment of neuropsychiatric function that is associated with impaired hepatic function. Because a patient with encephalopathy presents with an altered mental status, he or she may need to be admitted to the hospital for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment.

The goals of hepatic encephalopathy treatment are to identify and correct precipitating causes and lower serum ammonia concentrations to improve mental status.15 Nutritional support should be provided without protein restriction unless the patient is severely proteinintolerant.23 The recommended initial therapy is lactulose 30 to 45 mL 2 to 4 times per day, to decrease absorption of ammonia in the gut. The dose should be titrated until patients have 2 to 3 soft stools daily.24

For patients who can’t tolerate lactulose or whose mental status doesn’t improve within 48 hours, rifaximin 400 mg orally 3 times daily or 550 mg 2 times daily is recommended.25 Neomycin 500 mg orally 3 times a day or 1 g twice daily is a second-line agent reserved for patients who are unable to take rifaximin; however, its efficacy is not well established, and neomycin has been associated with ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.24

Watch for signs of kidney failure

Hepatorenal syndrome is renal failure induced by severe hepatic injury and characterized by azotemia and decreased renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate.15 It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Hepatorenal syndrome is typically caused by arterial vasodilation in the splanchnic circulation in patients with portal hypertension.15,26,27 Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by at least a 2-fold increase in serum creatinine to a level of >2.5 mg/dL over more than 2 weeks. Patients typically have urine output <400 to 500 mL/d. Type 2 hepatorenal syndrome is characterized by less severe renal impairment; it is associated with ascites that does not improve with diuretics.28

Patients with hepatorenal syndrome should not use any nephrotoxic agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Inpatient treatment is usually required and may include norepinephrine with albumin, terlipressin with midodrine, or octreotide and albumin. Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy may benefit from TIPS as a bridge until they can undergo liver transplantation.29

When to consider liver transplantation

The appropriateness and timing of liver transplantation should be determined on a case-by-case basis. For some patients with cirrhosis, transplantation may be the definitive treatment. For example, in some patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation is an option because transplantation can cure the tumor and underlying cirrhosis. However, while transplantation is a suitable option for early HCC in patients with cirrhosis, it has been shown to have limited efficacy in patients with advanced disease who are not selected using specific criteria.30

Referral for evaluation for transplantation should be considered once a patient with cirrhosis experiences a major complication (eg, ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy).31 Another criterion for timing and allocation of liver transplantation is based on the statistical model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), which is used to predict 3-month survival in patients with cirrhosis based on the relationships between serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and international normalized ratio values.15 Liver transplantation should be considered for patients with a MELD score ≥15.15,31 Such patients should be promptly referred to a liver transplantation specialist to allow sufficient time for the appropriate psychosocial assessments and medical evaluations, and for patients and their families to receive appropriate education on things like the risks and benefits of transplantation.15

Patients with cirrhosis should be educated about complications of their condition, including ascites, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).5 It’s important to explain that they will need to be evaluated every 6 months with serology and ultrasound to assess disease changes.6 Annual screening for HCC should be done with ultrasound or computed tomography scanning with or without alpha-fetoprotein.6

Ensure that your patient knows that he needs to receive the recommended immunizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that patients with cirrhosis should receive annual influenza, pneumococcal 23, and hepatitis A and B series vaccinations.7

Advise patients with cirrhosis to be cautious when taking any medications. Patients with cirrhosis should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because these medications encourage sodium retention, which can exacerbate ascites.6 Acetaminophen use is discouraged, but should not be harmful unless the patient takes >2 g/d.8

Emphasize the importance of eating a healthy diet. Malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis3 and correlates with more severe disease and poorer outcomes, including mortality.9 Nutritional recommendations for patients with alcohol-related liver disease include thiamine 50 mg orally or intramuscularly, and riboflavin and pyridoxine in the recommended daily doses.10 Advise patients to take other vitamins, as needed, to treat any deficiencies.9

CASE › After evaluating Mr. M, you prescribe spironolactone 100 mg/d and furosemide 40 mg twice a day to address ascites, and propranolol—which you titrate to 80 mg twice a day—to prevent variceal hemorrhage. Mr. M is maintained on these medications and returns with his daughter, as he has been doing every 2 to 3 months. He is excited that he breathes easily as long as he avoids salt and takes his medications. He continues to see his hepatologist regularly, and his last paracentesis was 4 months ago. He has not used any alcohol since he was taught about the relationship between alcohol and his breathing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Suzanne Minor, MD, FAAF P, Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Humanities, Health, & Society, Florida International University, Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, 11200 SW 8th Street, AHC II, 554A, Miami, FL 33199; [email protected]

1. Scaglion S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: A population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014. October 8. [Epub ahead of print.]

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2015.

3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Cirrhosis. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Web site. Available at: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/liver-disease/cirrhosis/Pages/facts.aspx. Accessed April 30, 2015.

4. Zhou WC, Zhang QB, Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7312-7324.

5. Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:1646-1654.

6. Grattagliano I, Ubaldi E, Bonfrate L, et al. Management of liver cirrhosis between primary care and specialists. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2273-2282.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 recommended immunizations for adults: By age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule-easyread.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2015.

8. Bacon BR. Cirrhosis and its complications. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. Available from: http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79748841. Accessed April 28, 2015.

9. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:14-32.

10. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert. Alcoholic liver disease. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2005. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa64/aa64.htm. Accessed April 18, 2015.

11. Kashani A, Landaverde C, Medici V, et al. Fluid retention in cirrhosis: pathophysiology and management. QJM. 2008;101:71-85.

12. Chalasani NP, Vuppalanchi RK. Ascites: A common problem in people with cirrhosis. July 2013. American College of Gastroenterology Web site. Available at: http://patients.gi.org/topics/ascites/. Accessed April 28, 2015.

13. Kuiper JJ, van Buuren HR, de Man RA. Ascites in cirrhosis: a review of management and complications. Neth J Med. 2007;65:283-288.

14. Biecker E. Diagnosis and therapy of ascites in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroentol. 2011;17:1237-1248.

15. Heidelbaugh JJ, Sherbondy M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: Part II. Complications and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:767-776.

16. Garcia-Tsao G, Lim JK; Members of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program. Management and treatment of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1802-1829.

17. Infante-Rivard C, Esnaola S, Villeneuve JP. Clinical and statistical validity of conventional prognostic factors in predicting shortterm survival among cirrhotics. Hepatology. 1987;7:660-664.

18. Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, et al; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938.

19. Serste T, Melot C, Francoz C, et al. Deleterious effects of betablockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010;52:1017-1022.

20. Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective b blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1680–1690.e1.

21. Sarin SK, Lamba GS, Kumar M, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:988-993.

22. Garcia-Pagan JC, Feu F, Bosch J, et al. Propranolol compared with propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. A randomized controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:869-873.

23. Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325-336.

24. Sharma P, Sharma BC. Disaccharides in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:313-320.

25. Jiang Q, Jiang XH, Zheng MH, et al. Rifaximin versus nonabsorbable disaccharides in the management of hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1064-1070.

26. Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1279-1290.

27. Iwakiri Y. The molecules: mechanisms of arterial vasodilatation observed in the splanchnic and systemic circulation in portal hypertension. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(Suppl 3):S288-S294.

28. Epstein M, Berk DP, Hollenberg NK, et al. Renal failure in the patient with cirrhosis. The role of active vasoconstriction. Am J Med. 1970;49:175-185.

29. Singh V, Ghosh S, Singh B, et al. Noradrenaline vs. terlipressin in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1293-1298.

30. Chua TC, Saxena A, Chu F, et al. Hepatic resection for transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma for patients within Milan and UCSF criteria. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:141-145.

31. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144-1165.

1. Scaglion S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: A population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014. October 8. [Epub ahead of print.]

2. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2015.

3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Cirrhosis. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Web site. Available at: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/liver-disease/cirrhosis/Pages/facts.aspx. Accessed April 30, 2015.

4. Zhou WC, Zhang QB, Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7312-7324.

5. Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:1646-1654.

6. Grattagliano I, Ubaldi E, Bonfrate L, et al. Management of liver cirrhosis between primary care and specialists. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2273-2282.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 recommended immunizations for adults: By age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule-easyread.pdf. Accessed April 28, 2015.

8. Bacon BR. Cirrhosis and its complications. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. Available from: http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79748841. Accessed April 28, 2015.

9. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:14-32.

10. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert. Alcoholic liver disease. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2005. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa64/aa64.htm. Accessed April 18, 2015.

11. Kashani A, Landaverde C, Medici V, et al. Fluid retention in cirrhosis: pathophysiology and management. QJM. 2008;101:71-85.

12. Chalasani NP, Vuppalanchi RK. Ascites: A common problem in people with cirrhosis. July 2013. American College of Gastroenterology Web site. Available at: http://patients.gi.org/topics/ascites/. Accessed April 28, 2015.

13. Kuiper JJ, van Buuren HR, de Man RA. Ascites in cirrhosis: a review of management and complications. Neth J Med. 2007;65:283-288.

14. Biecker E. Diagnosis and therapy of ascites in liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroentol. 2011;17:1237-1248.

15. Heidelbaugh JJ, Sherbondy M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: Part II. Complications and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:767-776.

16. Garcia-Tsao G, Lim JK; Members of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program. Management and treatment of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1802-1829.

17. Infante-Rivard C, Esnaola S, Villeneuve JP. Clinical and statistical validity of conventional prognostic factors in predicting shortterm survival among cirrhotics. Hepatology. 1987;7:660-664.

18. Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, et al; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938.

19. Serste T, Melot C, Francoz C, et al. Deleterious effects of betablockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010;52:1017-1022.

20. Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, et al. Nonselective b blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1680–1690.e1.

21. Sarin SK, Lamba GS, Kumar M, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:988-993.

22. Garcia-Pagan JC, Feu F, Bosch J, et al. Propranolol compared with propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. A randomized controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:869-873.

23. Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325-336.

24. Sharma P, Sharma BC. Disaccharides in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:313-320.

25. Jiang Q, Jiang XH, Zheng MH, et al. Rifaximin versus nonabsorbable disaccharides in the management of hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1064-1070.

26. Ginès P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1279-1290.

27. Iwakiri Y. The molecules: mechanisms of arterial vasodilatation observed in the splanchnic and systemic circulation in portal hypertension. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(Suppl 3):S288-S294.

28. Epstein M, Berk DP, Hollenberg NK, et al. Renal failure in the patient with cirrhosis. The role of active vasoconstriction. Am J Med. 1970;49:175-185.

29. Singh V, Ghosh S, Singh B, et al. Noradrenaline vs. terlipressin in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1293-1298.

30. Chua TC, Saxena A, Chu F, et al. Hepatic resection for transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma for patients within Milan and UCSF criteria. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:141-145.

31. Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144-1165.