User login

PHILADELPHIA – Closed-loop insulin therapy improved nocturnal glycemic control among 10 children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 7 years of age, Dr. Andrew Dauber reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The effectiveness of closed-loop insulin delivery using a pump combined with a continuous glucose sensor and a controller algorithm – the so-called "artificial pancreas" – has been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes, but no studies have been conducted in children younger than 7 years old. They are at increased risk for hypoglycemia, particularly at night, and there is particular concern that repeated hypoglycemic episodes could lead to neurocognitive deficits in that age group, Dr. Dauber said. Both eating and activity patterns among young children tend to be erratic and unpredictable, making accurate insulin dosing difficult, he added.

"We believe this is an underrepresented group in research studies and that they need dedicated research in the development of an artificial pancreas," said Dr. Dauber, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Hospital Boston.

The 10 children were aged 2.0-6.8 years (mean 5.1) and had a diabetes duration of 0.5-4.7 years (mean 2.1). At baseline, their hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 7.1% to 8.9%, with a mean of 8.1%. Seven of the 10 children had HbA1c values of less than 8.5%, the American Diabetes Association’s target for children in that age group. Average daily insulin doses ranged from 0.61 to 1.0 units/kg (mean 0.72).

The closed-loop system included a physiological insulin delivery algorithm using proportional-integral-derivative terms that were modified by insulin feedback. During the overnight (10 p.m. to 8 a.m.) control period, basal rates were manually adjusted every 20 minutes based on the sensor readings. During the morning (8 a.m. to noon), mini-boluses of insulin were given every minute based on sensor readings. Target blood sugars were 150 mg/dL during 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. and 120 mg/dL during 6 a.m. to noon. The afternoon was spent in standard pump therapy.

The children were admitted to the research unit for 48 hours and given identical meals each day. No meal boluses were given during the closed-loop period. Each child spent one day on the closed-loop system during the overnight and morning, and another day with standard pump therapy (in random order).

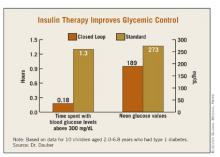

Time spent in target glucose range of 110-200 mg/dL overnight was higher with the closed-loop system, 3.2 vs. 5.3 hours, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .12). However, the closed-loop system significantly reduced the time spent with blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dL (0.18 vs. 1.3 hours, P = .035) and the noon glucose values (189 vs. 273 mg/dL, P = .009). Postprandial peaks were nearly identical (367 mg/dL closed-loop vs. 353 mg/dL open-loop) as were the number of interventions needed to treat hypoglycemia (5 vs. 4).

"Closed-loop therapy decreased the degree of nocturnal hyperglycemia in young children without increasing the incidence of hypoglycemia, and improved prelunch blood sugars. We believe closed-loop therapy has the potential to improve diabetes care for very young children," Dr. Dauber said.

Dr. Dauber received research support from Abbott Diabetes Care, Animas Corporation, and HemoCue Inc. which provided supplies for the study. The companies played no role in the design and conduct of the study, or in the collection, management, or interpretation of the data, he reported.

PHILADELPHIA – Closed-loop insulin therapy improved nocturnal glycemic control among 10 children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 7 years of age, Dr. Andrew Dauber reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The effectiveness of closed-loop insulin delivery using a pump combined with a continuous glucose sensor and a controller algorithm – the so-called "artificial pancreas" – has been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes, but no studies have been conducted in children younger than 7 years old. They are at increased risk for hypoglycemia, particularly at night, and there is particular concern that repeated hypoglycemic episodes could lead to neurocognitive deficits in that age group, Dr. Dauber said. Both eating and activity patterns among young children tend to be erratic and unpredictable, making accurate insulin dosing difficult, he added.

"We believe this is an underrepresented group in research studies and that they need dedicated research in the development of an artificial pancreas," said Dr. Dauber, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Hospital Boston.

The 10 children were aged 2.0-6.8 years (mean 5.1) and had a diabetes duration of 0.5-4.7 years (mean 2.1). At baseline, their hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 7.1% to 8.9%, with a mean of 8.1%. Seven of the 10 children had HbA1c values of less than 8.5%, the American Diabetes Association’s target for children in that age group. Average daily insulin doses ranged from 0.61 to 1.0 units/kg (mean 0.72).

The closed-loop system included a physiological insulin delivery algorithm using proportional-integral-derivative terms that were modified by insulin feedback. During the overnight (10 p.m. to 8 a.m.) control period, basal rates were manually adjusted every 20 minutes based on the sensor readings. During the morning (8 a.m. to noon), mini-boluses of insulin were given every minute based on sensor readings. Target blood sugars were 150 mg/dL during 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. and 120 mg/dL during 6 a.m. to noon. The afternoon was spent in standard pump therapy.

The children were admitted to the research unit for 48 hours and given identical meals each day. No meal boluses were given during the closed-loop period. Each child spent one day on the closed-loop system during the overnight and morning, and another day with standard pump therapy (in random order).

Time spent in target glucose range of 110-200 mg/dL overnight was higher with the closed-loop system, 3.2 vs. 5.3 hours, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .12). However, the closed-loop system significantly reduced the time spent with blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dL (0.18 vs. 1.3 hours, P = .035) and the noon glucose values (189 vs. 273 mg/dL, P = .009). Postprandial peaks were nearly identical (367 mg/dL closed-loop vs. 353 mg/dL open-loop) as were the number of interventions needed to treat hypoglycemia (5 vs. 4).

"Closed-loop therapy decreased the degree of nocturnal hyperglycemia in young children without increasing the incidence of hypoglycemia, and improved prelunch blood sugars. We believe closed-loop therapy has the potential to improve diabetes care for very young children," Dr. Dauber said.

Dr. Dauber received research support from Abbott Diabetes Care, Animas Corporation, and HemoCue Inc. which provided supplies for the study. The companies played no role in the design and conduct of the study, or in the collection, management, or interpretation of the data, he reported.

PHILADELPHIA – Closed-loop insulin therapy improved nocturnal glycemic control among 10 children with type 1 diabetes who were younger than 7 years of age, Dr. Andrew Dauber reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The effectiveness of closed-loop insulin delivery using a pump combined with a continuous glucose sensor and a controller algorithm – the so-called "artificial pancreas" – has been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes, but no studies have been conducted in children younger than 7 years old. They are at increased risk for hypoglycemia, particularly at night, and there is particular concern that repeated hypoglycemic episodes could lead to neurocognitive deficits in that age group, Dr. Dauber said. Both eating and activity patterns among young children tend to be erratic and unpredictable, making accurate insulin dosing difficult, he added.

"We believe this is an underrepresented group in research studies and that they need dedicated research in the development of an artificial pancreas," said Dr. Dauber, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s Hospital Boston.

The 10 children were aged 2.0-6.8 years (mean 5.1) and had a diabetes duration of 0.5-4.7 years (mean 2.1). At baseline, their hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 7.1% to 8.9%, with a mean of 8.1%. Seven of the 10 children had HbA1c values of less than 8.5%, the American Diabetes Association’s target for children in that age group. Average daily insulin doses ranged from 0.61 to 1.0 units/kg (mean 0.72).

The closed-loop system included a physiological insulin delivery algorithm using proportional-integral-derivative terms that were modified by insulin feedback. During the overnight (10 p.m. to 8 a.m.) control period, basal rates were manually adjusted every 20 minutes based on the sensor readings. During the morning (8 a.m. to noon), mini-boluses of insulin were given every minute based on sensor readings. Target blood sugars were 150 mg/dL during 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. and 120 mg/dL during 6 a.m. to noon. The afternoon was spent in standard pump therapy.

The children were admitted to the research unit for 48 hours and given identical meals each day. No meal boluses were given during the closed-loop period. Each child spent one day on the closed-loop system during the overnight and morning, and another day with standard pump therapy (in random order).

Time spent in target glucose range of 110-200 mg/dL overnight was higher with the closed-loop system, 3.2 vs. 5.3 hours, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .12). However, the closed-loop system significantly reduced the time spent with blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dL (0.18 vs. 1.3 hours, P = .035) and the noon glucose values (189 vs. 273 mg/dL, P = .009). Postprandial peaks were nearly identical (367 mg/dL closed-loop vs. 353 mg/dL open-loop) as were the number of interventions needed to treat hypoglycemia (5 vs. 4).

"Closed-loop therapy decreased the degree of nocturnal hyperglycemia in young children without increasing the incidence of hypoglycemia, and improved prelunch blood sugars. We believe closed-loop therapy has the potential to improve diabetes care for very young children," Dr. Dauber said.

Dr. Dauber received research support from Abbott Diabetes Care, Animas Corporation, and HemoCue Inc. which provided supplies for the study. The companies played no role in the design and conduct of the study, or in the collection, management, or interpretation of the data, he reported.

AT THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: The closed-loop system significantly reduced the time spent with blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dL (0.18 vs. 1.3 hours) and the noon glucose values (189 vs. 273 mg/dL).

Data Source: The data come from a randomized crossover inpatient study of 10 children younger than 7 years of age with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: Dr. Dauber received research support from Abbott Diabetes Care, Animas Corporation, and HemoCue Inc. which provided supplies for the study. However, the companies played no role in the design and conduct of the study, or in the collection, management, or interpretation of the data.