User login

"Why do I need to do research if I’m going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature. This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision-making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery. Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies. Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings. Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat. There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor, a topic, a clear, novel question, and the appropriate study design. Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiothoracic surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon.

The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time. The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor who is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals. Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

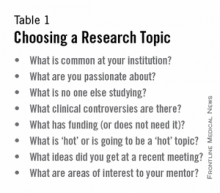

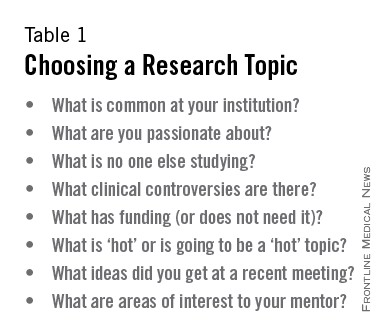

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?" Stay away from the lure of "Let’s review our experience of operation X..." or "Why don’t I see how many of operation Y we’ve done over the past 10 years..." These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

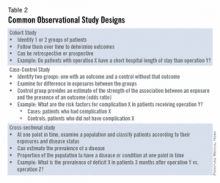

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee. The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2). Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

When designing a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori endpoints. Every study will have one primary endpoint that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you only do it once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature, and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results. Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval.

This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

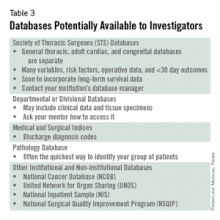

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project.

Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity). Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data regardless of whether the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward.

Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct. Next, using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript.

Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study. Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product.

Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing. Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you. Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don’t know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions.

Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study. You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center.

"Why do I need to do research if I’m going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature. This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision-making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery. Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies. Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings. Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat. There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor, a topic, a clear, novel question, and the appropriate study design. Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiothoracic surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon.

The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time. The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor who is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals. Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?" Stay away from the lure of "Let’s review our experience of operation X..." or "Why don’t I see how many of operation Y we’ve done over the past 10 years..." These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee. The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2). Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

When designing a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori endpoints. Every study will have one primary endpoint that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you only do it once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature, and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results. Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval.

This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project.

Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity). Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data regardless of whether the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward.

Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct. Next, using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript.

Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study. Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product.

Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing. Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you. Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don’t know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions.

Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study. You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center.

"Why do I need to do research if I’m going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature. This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision-making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery. Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies. Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings. Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat. There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor, a topic, a clear, novel question, and the appropriate study design. Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiothoracic surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon.

The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time. The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor who is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals. Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?" Stay away from the lure of "Let’s review our experience of operation X..." or "Why don’t I see how many of operation Y we’ve done over the past 10 years..." These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee. The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2). Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

When designing a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori endpoints. Every study will have one primary endpoint that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you only do it once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature, and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results. Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval.

This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project.

Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity). Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data regardless of whether the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward.

Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct. Next, using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript.

Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study. Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product.

Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing. Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you. Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don’t know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions.

Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study. You will meet lifelong colleagues, and maybe even your future partner. For many, research is a rewarding lifelong endeavor. For others, it is a means of learning to critically appraise the literature and landing a job. Either way, you cannot afford not to do research as a trainee.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr. Stephen H. McKellar (University of Utah), for his advice on performing research as a cardiothoracic trainee.

Dr. Seder is in the department of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at Rush University Medical Center.