User login

Reflections on women in surgery

As I reflect upon the past year, 2018 has certainly made a mark for addressing burnout among medical professionals, enforcing wellness, and targeting implicit and explicit gender bias in medicine and surgery.

Looking back, I entered surgery with a dream to change the culture of surgery. I knew I didn’t fit the traditional mold of an aggressive or arrogant surgeon. But I thought that my empathetic, open, and compassionate ways may spark a change in paradigm for that traditional surgical ideology. However, what I encountered as I made my way on this long, ever-winding journey was a system, culture, and tradition that beats you down, and what I thought were my strengths were quickly turned into weaknesses. As I grew and matured, this loss of identity in a culture of depersonalization surrounded by gender bias, for me, was a perfect recipe leading straight to burnout. However, this was an impetus for change, to be that voice and spark for a cultural transformation of surgery and for the women who work in the specialty.

More women are entering medical and surgical specialties. However, despite the advances made there are still clear gender-based disparities influencing overall wellness and work satisfaction. For instance, a study by Meyerson et al. demonstrated that female residents receive less operating room autonomy than male ones. I see it daily within my own curriculum and in observing other female residents in other surgical specialties. Furthermore, female residents are less often introduced by their physician titles, compared with their male counterparts, are often confused as nonphysicians, and are perceived as being less competent. This influences, to no small extent, overall confidence. It’s discouraging and disheartening to have worked so hard and yet still be treated in a sexist paradigm. And to top it all off, female physicians face a motherhood penalty.

In a recent study by Magudia et al., out of 12 top medical institutions that provided maternity leave, only 8 did so for residents with a grant total of 6.6 weeks on average. Furthermore, women with children or women who plan to have children have constrained career opportunities and are less likely to get full professorship or leadership positions. Anecdotally, a surgeon in passing semijokingly told me that if I were to take a specific academic vascular position, I may have to sign an agreement not to get pregnant ... probably not the job for me.

It’s appalling that, in this day and age, these explicit beliefs still exist, but what scares me more are all the implicit unconscious biases that affect all women not only in surgery but in medicine as well.

Looking back, 2018 is a year of beginning difficult conversations about physician and surgeon wellness, burnout, and gender bias. What’s obvious is that there is a hell of a lot of work to do. But change is slowly starting. We are now recognizing what the issues are, and the next step is to take action. It’s difficult to steer big ships, but there is an active community investing in strategies to improve the cultural scope of surgery and supporting and valuing women and what they have to offer.

References

Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2372-4.

Meyerson SL et al. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e111-18.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

As I reflect upon the past year, 2018 has certainly made a mark for addressing burnout among medical professionals, enforcing wellness, and targeting implicit and explicit gender bias in medicine and surgery.

Looking back, I entered surgery with a dream to change the culture of surgery. I knew I didn’t fit the traditional mold of an aggressive or arrogant surgeon. But I thought that my empathetic, open, and compassionate ways may spark a change in paradigm for that traditional surgical ideology. However, what I encountered as I made my way on this long, ever-winding journey was a system, culture, and tradition that beats you down, and what I thought were my strengths were quickly turned into weaknesses. As I grew and matured, this loss of identity in a culture of depersonalization surrounded by gender bias, for me, was a perfect recipe leading straight to burnout. However, this was an impetus for change, to be that voice and spark for a cultural transformation of surgery and for the women who work in the specialty.

More women are entering medical and surgical specialties. However, despite the advances made there are still clear gender-based disparities influencing overall wellness and work satisfaction. For instance, a study by Meyerson et al. demonstrated that female residents receive less operating room autonomy than male ones. I see it daily within my own curriculum and in observing other female residents in other surgical specialties. Furthermore, female residents are less often introduced by their physician titles, compared with their male counterparts, are often confused as nonphysicians, and are perceived as being less competent. This influences, to no small extent, overall confidence. It’s discouraging and disheartening to have worked so hard and yet still be treated in a sexist paradigm. And to top it all off, female physicians face a motherhood penalty.

In a recent study by Magudia et al., out of 12 top medical institutions that provided maternity leave, only 8 did so for residents with a grant total of 6.6 weeks on average. Furthermore, women with children or women who plan to have children have constrained career opportunities and are less likely to get full professorship or leadership positions. Anecdotally, a surgeon in passing semijokingly told me that if I were to take a specific academic vascular position, I may have to sign an agreement not to get pregnant ... probably not the job for me.

It’s appalling that, in this day and age, these explicit beliefs still exist, but what scares me more are all the implicit unconscious biases that affect all women not only in surgery but in medicine as well.

Looking back, 2018 is a year of beginning difficult conversations about physician and surgeon wellness, burnout, and gender bias. What’s obvious is that there is a hell of a lot of work to do. But change is slowly starting. We are now recognizing what the issues are, and the next step is to take action. It’s difficult to steer big ships, but there is an active community investing in strategies to improve the cultural scope of surgery and supporting and valuing women and what they have to offer.

References

Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2372-4.

Meyerson SL et al. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e111-18.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

As I reflect upon the past year, 2018 has certainly made a mark for addressing burnout among medical professionals, enforcing wellness, and targeting implicit and explicit gender bias in medicine and surgery.

Looking back, I entered surgery with a dream to change the culture of surgery. I knew I didn’t fit the traditional mold of an aggressive or arrogant surgeon. But I thought that my empathetic, open, and compassionate ways may spark a change in paradigm for that traditional surgical ideology. However, what I encountered as I made my way on this long, ever-winding journey was a system, culture, and tradition that beats you down, and what I thought were my strengths were quickly turned into weaknesses. As I grew and matured, this loss of identity in a culture of depersonalization surrounded by gender bias, for me, was a perfect recipe leading straight to burnout. However, this was an impetus for change, to be that voice and spark for a cultural transformation of surgery and for the women who work in the specialty.

More women are entering medical and surgical specialties. However, despite the advances made there are still clear gender-based disparities influencing overall wellness and work satisfaction. For instance, a study by Meyerson et al. demonstrated that female residents receive less operating room autonomy than male ones. I see it daily within my own curriculum and in observing other female residents in other surgical specialties. Furthermore, female residents are less often introduced by their physician titles, compared with their male counterparts, are often confused as nonphysicians, and are perceived as being less competent. This influences, to no small extent, overall confidence. It’s discouraging and disheartening to have worked so hard and yet still be treated in a sexist paradigm. And to top it all off, female physicians face a motherhood penalty.

In a recent study by Magudia et al., out of 12 top medical institutions that provided maternity leave, only 8 did so for residents with a grant total of 6.6 weeks on average. Furthermore, women with children or women who plan to have children have constrained career opportunities and are less likely to get full professorship or leadership positions. Anecdotally, a surgeon in passing semijokingly told me that if I were to take a specific academic vascular position, I may have to sign an agreement not to get pregnant ... probably not the job for me.

It’s appalling that, in this day and age, these explicit beliefs still exist, but what scares me more are all the implicit unconscious biases that affect all women not only in surgery but in medicine as well.

Looking back, 2018 is a year of beginning difficult conversations about physician and surgeon wellness, burnout, and gender bias. What’s obvious is that there is a hell of a lot of work to do. But change is slowly starting. We are now recognizing what the issues are, and the next step is to take action. It’s difficult to steer big ships, but there is an active community investing in strategies to improve the cultural scope of surgery and supporting and valuing women and what they have to offer.

References

Magudia K et al. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2372-4.

Meyerson SL et al. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e111-18.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Taking a leap of faith

After a grueling first two years of surgical residency, I welcomed with open arms my surgical research years. Junior surgical residency was arguably the toughest years of my training to date. Long hours at the hospital; the uncertainty of being called in to the hospital when on-call, which led to chronic anxiety and at times insomnia; and the pressures I put on myself to excel in all aspects of my training were draining, to say the least.

Of course, when it came time to leave my clinical responsibilities and pursue my Master’s degree, I was overcome with relief. First, I got my life back on track, leading a life of optimal nutrition, physical activity, and sleep and exploring different horizons in surgery.

Second, this time allowed me to grow as a person, learning techniques to remain calm in the face of adversity, to take at least 10 minutes a day for mindfulness, and to be cognizant and gauge when I am creeping upon that tipping point. I believe the key to success and happiness is to keep re-evaluating and being honest with ourselves, our happiness, our stresses, and our anxieties and to reach out to pillars of support, whoever they may be.

And finally, we are fundamentally teachers and inspirations to the next generation of surgeons who will follow in our footsteps. By being open, encouraging, and sharing our enthusiasm for our specialty, our patients, and our research, we may see the seeds of the future flourish under our wings.

That being said, I am terrified of returning to vascular surgery. I know it will be a challenge transitioning to senior resident, and I am scared that the progress I made over these years in terms of wellness and wellbeing will regress; however, in the end, I have to take a leap of faith and hope it all pulls together ... seamlessly.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

After a grueling first two years of surgical residency, I welcomed with open arms my surgical research years. Junior surgical residency was arguably the toughest years of my training to date. Long hours at the hospital; the uncertainty of being called in to the hospital when on-call, which led to chronic anxiety and at times insomnia; and the pressures I put on myself to excel in all aspects of my training were draining, to say the least.

Of course, when it came time to leave my clinical responsibilities and pursue my Master’s degree, I was overcome with relief. First, I got my life back on track, leading a life of optimal nutrition, physical activity, and sleep and exploring different horizons in surgery.

Second, this time allowed me to grow as a person, learning techniques to remain calm in the face of adversity, to take at least 10 minutes a day for mindfulness, and to be cognizant and gauge when I am creeping upon that tipping point. I believe the key to success and happiness is to keep re-evaluating and being honest with ourselves, our happiness, our stresses, and our anxieties and to reach out to pillars of support, whoever they may be.

And finally, we are fundamentally teachers and inspirations to the next generation of surgeons who will follow in our footsteps. By being open, encouraging, and sharing our enthusiasm for our specialty, our patients, and our research, we may see the seeds of the future flourish under our wings.

That being said, I am terrified of returning to vascular surgery. I know it will be a challenge transitioning to senior resident, and I am scared that the progress I made over these years in terms of wellness and wellbeing will regress; however, in the end, I have to take a leap of faith and hope it all pulls together ... seamlessly.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

After a grueling first two years of surgical residency, I welcomed with open arms my surgical research years. Junior surgical residency was arguably the toughest years of my training to date. Long hours at the hospital; the uncertainty of being called in to the hospital when on-call, which led to chronic anxiety and at times insomnia; and the pressures I put on myself to excel in all aspects of my training were draining, to say the least.

Of course, when it came time to leave my clinical responsibilities and pursue my Master’s degree, I was overcome with relief. First, I got my life back on track, leading a life of optimal nutrition, physical activity, and sleep and exploring different horizons in surgery.

Second, this time allowed me to grow as a person, learning techniques to remain calm in the face of adversity, to take at least 10 minutes a day for mindfulness, and to be cognizant and gauge when I am creeping upon that tipping point. I believe the key to success and happiness is to keep re-evaluating and being honest with ourselves, our happiness, our stresses, and our anxieties and to reach out to pillars of support, whoever they may be.

And finally, we are fundamentally teachers and inspirations to the next generation of surgeons who will follow in our footsteps. By being open, encouraging, and sharing our enthusiasm for our specialty, our patients, and our research, we may see the seeds of the future flourish under our wings.

That being said, I am terrified of returning to vascular surgery. I know it will be a challenge transitioning to senior resident, and I am scared that the progress I made over these years in terms of wellness and wellbeing will regress; however, in the end, I have to take a leap of faith and hope it all pulls together ... seamlessly.

Dr. Drudi is a vascular surgery resident at McGill University, Montreal, and the resident medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Residency is like an IRONMAN

At the end of my junior surgical residency years, I was in a pretty bad physical and mental space. With resident coverage shortages, long hours, chronic fatigue, and personal pressures to perform and shine, I wound up digging myself into a hole, heading straight to resident burnout. Although there were others around me experiencing similar environmental stressors, I certainly felt alone – not knowing how to climb out of the hole I created for myself.

This was probably the lowest I have been in my life, but I finally got myself back on track. Coming from a fairly physically active background, I returned to a life of proper nutrition and physical activity. I began swimming, biking, and running, with the hopes of maybe one day doing a triathlon. There were a few health care professionals at my institution who competed in yearly triathlons, which certainly inspired me to take up the sport. So, last August, I signed up for my first Half-IRONMAN in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, and had roughly 10 months to train. Looking back, I am not sure what possessed me to think I could achieve such a feat, but it was certainly a goal to work toward.

First, take it slow and steady. Residency is long and arduous, and it is easy to overpace yourself in the first few months – but keep in mind that you are in it for the long haul (for some, it’s longer than 5 years).

Second, be nice to your body and mind. You wouldn’t believe how some of the most-challenging experiences are all psychological; therefore, eat well, sleep well, and practice mindfulness every day. Develop a routine early on, so that when you meet grueling experiences and challenges, your routine will make you equipped to overcome them. The practice of mindfulness (a mental state of being aware in the present moment) will be unique to each individual and may be performed through exercising, yoga, or more traditionally, through meditation. Third, develop or strengthen a support system to help you identify and overcome problems that you may face during residency.

Ideally, this will be a support system (for example, residents, coworkers, and staff) that know exactly what you will be facing and offer constructive advice for the trials and tribulations you will be confronting. Finally, residency will be the most-challenging experience you may go through yet in your pursuit of postgraduate medical education. You are not alone on this journey, and the path to success will be burdened with physical and mental exhaustion, tears, groans, as well as smiles. But when you cross that finish line, let me tell you that the emotions that will overwhelm you will be those of complete exuberance and utter disbelief that you had the courage and determination to not only undertake the challenge but to succeed, as well.

At the end of my junior surgical residency years, I was in a pretty bad physical and mental space. With resident coverage shortages, long hours, chronic fatigue, and personal pressures to perform and shine, I wound up digging myself into a hole, heading straight to resident burnout. Although there were others around me experiencing similar environmental stressors, I certainly felt alone – not knowing how to climb out of the hole I created for myself.

This was probably the lowest I have been in my life, but I finally got myself back on track. Coming from a fairly physically active background, I returned to a life of proper nutrition and physical activity. I began swimming, biking, and running, with the hopes of maybe one day doing a triathlon. There were a few health care professionals at my institution who competed in yearly triathlons, which certainly inspired me to take up the sport. So, last August, I signed up for my first Half-IRONMAN in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, and had roughly 10 months to train. Looking back, I am not sure what possessed me to think I could achieve such a feat, but it was certainly a goal to work toward.

First, take it slow and steady. Residency is long and arduous, and it is easy to overpace yourself in the first few months – but keep in mind that you are in it for the long haul (for some, it’s longer than 5 years).

Second, be nice to your body and mind. You wouldn’t believe how some of the most-challenging experiences are all psychological; therefore, eat well, sleep well, and practice mindfulness every day. Develop a routine early on, so that when you meet grueling experiences and challenges, your routine will make you equipped to overcome them. The practice of mindfulness (a mental state of being aware in the present moment) will be unique to each individual and may be performed through exercising, yoga, or more traditionally, through meditation. Third, develop or strengthen a support system to help you identify and overcome problems that you may face during residency.

Ideally, this will be a support system (for example, residents, coworkers, and staff) that know exactly what you will be facing and offer constructive advice for the trials and tribulations you will be confronting. Finally, residency will be the most-challenging experience you may go through yet in your pursuit of postgraduate medical education. You are not alone on this journey, and the path to success will be burdened with physical and mental exhaustion, tears, groans, as well as smiles. But when you cross that finish line, let me tell you that the emotions that will overwhelm you will be those of complete exuberance and utter disbelief that you had the courage and determination to not only undertake the challenge but to succeed, as well.

At the end of my junior surgical residency years, I was in a pretty bad physical and mental space. With resident coverage shortages, long hours, chronic fatigue, and personal pressures to perform and shine, I wound up digging myself into a hole, heading straight to resident burnout. Although there were others around me experiencing similar environmental stressors, I certainly felt alone – not knowing how to climb out of the hole I created for myself.

This was probably the lowest I have been in my life, but I finally got myself back on track. Coming from a fairly physically active background, I returned to a life of proper nutrition and physical activity. I began swimming, biking, and running, with the hopes of maybe one day doing a triathlon. There were a few health care professionals at my institution who competed in yearly triathlons, which certainly inspired me to take up the sport. So, last August, I signed up for my first Half-IRONMAN in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, and had roughly 10 months to train. Looking back, I am not sure what possessed me to think I could achieve such a feat, but it was certainly a goal to work toward.

First, take it slow and steady. Residency is long and arduous, and it is easy to overpace yourself in the first few months – but keep in mind that you are in it for the long haul (for some, it’s longer than 5 years).

Second, be nice to your body and mind. You wouldn’t believe how some of the most-challenging experiences are all psychological; therefore, eat well, sleep well, and practice mindfulness every day. Develop a routine early on, so that when you meet grueling experiences and challenges, your routine will make you equipped to overcome them. The practice of mindfulness (a mental state of being aware in the present moment) will be unique to each individual and may be performed through exercising, yoga, or more traditionally, through meditation. Third, develop or strengthen a support system to help you identify and overcome problems that you may face during residency.

Ideally, this will be a support system (for example, residents, coworkers, and staff) that know exactly what you will be facing and offer constructive advice for the trials and tribulations you will be confronting. Finally, residency will be the most-challenging experience you may go through yet in your pursuit of postgraduate medical education. You are not alone on this journey, and the path to success will be burdened with physical and mental exhaustion, tears, groans, as well as smiles. But when you cross that finish line, let me tell you that the emotions that will overwhelm you will be those of complete exuberance and utter disbelief that you had the courage and determination to not only undertake the challenge but to succeed, as well.

Commentary: Should board exams include a technical skill assessment? A European perspective

The incidence of vascular diseases is steadily increasing because of an aging population. Vascular surgery is the only specialty that can offer all modalities of vascular therapy (endovascular, open, and conservative). It is therefore necessary to ensure implementation of all these modalities in a modern vascular surgical curricula. The creation of a vascular specialist curriculum is undoubtedly the best way to overcome further fragmentation of vascular provision and to prevent the increasingly financially-driven incentives that can mislead treatment. For obvious reasons this would be a major benefit for our patients and for our specialty.

Another reason for updating the vascular surgical curricula is the significant reduction of open aortic and peripheral vascular surgical training cases, such as abdominal aortic aneurysms and superficial femoral artery occlusions.1 Since the vast majority of these patients are now treated by endovascular means, the remaining vascular disease morphologies can technically be very demanding when requiring open vascular surgery procedures.

Nevertheless, the public and our patients quite understandably expect to be treated by well trained and competent vascular surgeons/specialists. As in all other professions, a proper assessment of all vascular competencies is therefore considered to be mandatory at the end of the training period for a vascular specialist. To this end, several proposals have been made to improve both the structure and different assessment tools including the Vascular Surgical Milestones Project,2 the Vascular Surgery In-Training Examinations (VSITE),3 the use of procedure-based assessments (PBA),4 or objective structured assessments of technical skills (OSATS).5 In addition, simulation workshops (using computer- or life-like synthetic models) play an increasing role in teaching vascular residents the ever-increasing number of different open and endovascular surgical techniques.6,7

Traditionally, the final board examination at the end of the vascular surgical training period consists of an oral assessment or a computer-based test. The obvious crucial question is whether a practical examination should be a added as a mandatory part of a vascular exit exam. This article gives an overview of the board examination of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (EBVS) at the UEMS (Union of European Medical Specialists), which adopted a technical skills assessment in 2006.

The European Vascular Surgical Examination

The UEMS was founded in 1958 as an official body of the European Union (EU). The UEMS has the remits to accredit medical meetings,8 to promote free professional movement of all doctors within Europe, and to ensure high quality of training and associated specialist standards via UEMS examinations.9,10 Currently, the UEMS represents the national medical societies of 37 member states. To date there are 42 UEMS Specialist Sections (separate and independent disciplines), UEMS Divisions (key areas within the independent disciplines, such as Interventional Radiology) and some so-called “Multidisciplinary Joint Committees” (such as Phlebology).

Since 2005, vascular surgery has been represented as an independent medical discipline within the UEMS.Politically, this was a tremendously important step that has helped many European countries to establish vascular surgery on a national level as a separate specialty. The most recent examples are Switzerland (since 2014) and Austria (since 2015).

European vascular surgical examinations have been offered since 1996. The Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery (FEBVS) is voluntary in most European countries, but in some countries, such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, the European exam has now replaced the national specialist exam.12 Other countries also are in the process of accepting this European standard as a national standard, including Romania, Austria, and Sweden.

The European exam consists of a written section and a combined oral and practical exam. Candidates must be in possession of a national specialist title for surgery or vascular surgery (in countries with a monospecialty). Applications from non-EU countries also are accepted.

Applications must be made in writing, giving details of open-operative and endovascular experience. A distinction is made between assisted operations, independently performed surgery with assistance, and actual independently performed surgical procedures without specialist tutorial assistance. All candidates admitted to the examination have to pass a one-day oral and practical examination, which includes questioning on theoretical background knowledge and its practical application. This takes place mostly in the context of specific clinical case studies as well as via practical examinations on pulsatile perfused lifelike models.

The following procedures are assessed: an infrarenal aortic anastomosis, a carotid endarterectomy, and a distal bypass anastomosis.6,13,14 In the endovascular part of the examination, the applicant’s ability to introduce a guide-wire into the renal artery is assessed.15 Unlike the case in many national tests, FEBVS candidates are also presented with a specialist English-language publication (usually from the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery). This article is then discussed with two examiners, with respect to its quality as well as its methodological content and significance. Many examination candidates fear this hurdle the most, but in fact very few participants fail this part of the test.

The European exam is designed to be unbiased and fair, with two examiners at each test station who carry out their assessments independent of each other. During the course of the examination, each candidate is interviewed by approximately 10 assessors. The assessment is validated by way of an evaluation form. The assessing auditors’ communications skills are themselves judged by observers. In the event of communication difficulties, observers are subsequently consulted.

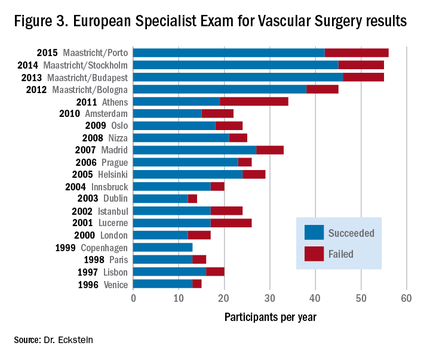

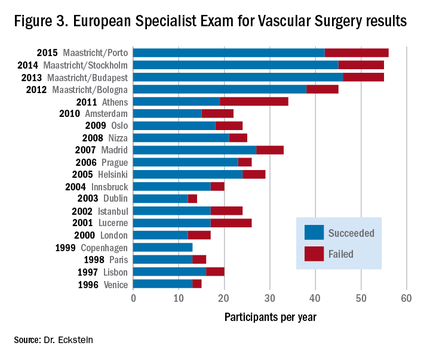

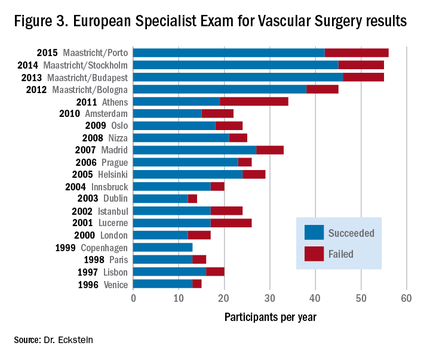

Despite the challenging test procedures, the number of participants in the European Specialist Exam for Vascular Surgery has steadily increased in recent years. For this reason, since 2012, two examination sessions per year have been offered, one during the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) and one at the European Vascular Course (EVC) in Maastricht. The failure rate each year fluctuates around 20%.

Benefits of being a Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS)

There are a number of very good reasons to sit a European examination and acquire the title of Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS). Some of them are:

Evidence of competency in job applications. Many managers know that the European exam is theoretically and practically challenging, and comprehensive. Confidence in candidates (specialists and senior physicians) who have passed the European test is therefore higher. That in turn increases the chances of getting the desired position especially when applying abroad!

Verification of open surgical and endovascular skills. Filling in the logbook16 helps to maintain a transparent open/endovascular portfolio. It is an extremely sophisticated tool to capture expertise and experience.

Commitment to the need for a European standard. The UEMS has set itself the goal of setting a European standard for medical specialists at the highest level. The European specialist exam projects this. All FEBVS support this goal via their application.

Commitment to academic knowledge-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers theoretical background, knowledge of the main studies, basic academic skills, and the ability to comprehensively apply this knowledge to case studies from the entire vascular field. By obtaining this exam, all FEBVS confirm their commitment to an evidence-based approach to vascular surgery.

Commitment to competency-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers a practical assessment on open vascular surgical and endovascular key competencies. By passing this part of the exam, all FEBVS give evidence that they are technically competent vascular surgeons.

Desire to belong to the best of the profession. The European specialist exam is certainly more demanding than many national board certifications. However, it offers an opportunity to belong to the European vascular surgical elite.

In conclusion, the European experience on board examinations including skills assessment shows pretty clearly that this sort of comprehensive examination is feasible. Moreover, the increasing number of applications indicates the growing attractiveness of the European certification and qualification as FEBVS. The long-term goal will be to make this examination mandatory for all EU countries – still a long way to go. By the way, since the status of FEBVS is also achievable by non-EU countries, Brexit will not prevent vascular surgeons from the United Kingdom to qualify as FEBVS in the future!

Dr. Eckstein is the Past President of the Board and Section of Vascular Surgery at the Union of European Medical Specialists (UEMS) and Past President of the German Vascular Society (DGG), and an associate editor for Vascular Specialist.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:945-49

2. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1140-6

3. Vascular surgery qualifying examination and Vsite

4. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:i-xxi, 1-162

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1422-8

8. International Angiology. 2007;26:361-6

9. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:109-15

10. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:69S-75S; discussion 75S

12. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:719-25

13. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1148-54

14. Brit J Surg. 2006;93:1132-8

|

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III |

Dr. Eckstein’s excellent review highlights the challenges the European Union faces in trying to standardize its certification in vascular surgery. Among European nations, the training pathways in vascular surgery are extremely varied, yet the European Economic Union calls for a medical specialist who is certified in one country to be able to practice that specialty in any EEU nation. While participation in the Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery is still mostly optional, it does provide a path toward a standard of quality that includes competence in open and endovascular procedures. In the United States, we face a similar dilemma with the advent of the integrated vascular residencies. Curricula, case volumes, and rotations still vary wildly between programs and in comparison with traditional fellowships. One solution is the Fundamentals of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (FVEVS) project. Currently in its pilot stage, the FVEVS is designed to ensure the attainment of basic technical competencies by the mid-trainee level so the later years are focused on advanced open and endovascular training.

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III is the Associate Medical Editor for Vascular Specialist.

|

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III |

Dr. Eckstein’s excellent review highlights the challenges the European Union faces in trying to standardize its certification in vascular surgery. Among European nations, the training pathways in vascular surgery are extremely varied, yet the European Economic Union calls for a medical specialist who is certified in one country to be able to practice that specialty in any EEU nation. While participation in the Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery is still mostly optional, it does provide a path toward a standard of quality that includes competence in open and endovascular procedures. In the United States, we face a similar dilemma with the advent of the integrated vascular residencies. Curricula, case volumes, and rotations still vary wildly between programs and in comparison with traditional fellowships. One solution is the Fundamentals of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (FVEVS) project. Currently in its pilot stage, the FVEVS is designed to ensure the attainment of basic technical competencies by the mid-trainee level so the later years are focused on advanced open and endovascular training.

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III is the Associate Medical Editor for Vascular Specialist.

|

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III |

Dr. Eckstein’s excellent review highlights the challenges the European Union faces in trying to standardize its certification in vascular surgery. Among European nations, the training pathways in vascular surgery are extremely varied, yet the European Economic Union calls for a medical specialist who is certified in one country to be able to practice that specialty in any EEU nation. While participation in the Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery is still mostly optional, it does provide a path toward a standard of quality that includes competence in open and endovascular procedures. In the United States, we face a similar dilemma with the advent of the integrated vascular residencies. Curricula, case volumes, and rotations still vary wildly between programs and in comparison with traditional fellowships. One solution is the Fundamentals of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (FVEVS) project. Currently in its pilot stage, the FVEVS is designed to ensure the attainment of basic technical competencies by the mid-trainee level so the later years are focused on advanced open and endovascular training.

Dr. Malachi Sheahan III is the Associate Medical Editor for Vascular Specialist.

The incidence of vascular diseases is steadily increasing because of an aging population. Vascular surgery is the only specialty that can offer all modalities of vascular therapy (endovascular, open, and conservative). It is therefore necessary to ensure implementation of all these modalities in a modern vascular surgical curricula. The creation of a vascular specialist curriculum is undoubtedly the best way to overcome further fragmentation of vascular provision and to prevent the increasingly financially-driven incentives that can mislead treatment. For obvious reasons this would be a major benefit for our patients and for our specialty.

Another reason for updating the vascular surgical curricula is the significant reduction of open aortic and peripheral vascular surgical training cases, such as abdominal aortic aneurysms and superficial femoral artery occlusions.1 Since the vast majority of these patients are now treated by endovascular means, the remaining vascular disease morphologies can technically be very demanding when requiring open vascular surgery procedures.

Nevertheless, the public and our patients quite understandably expect to be treated by well trained and competent vascular surgeons/specialists. As in all other professions, a proper assessment of all vascular competencies is therefore considered to be mandatory at the end of the training period for a vascular specialist. To this end, several proposals have been made to improve both the structure and different assessment tools including the Vascular Surgical Milestones Project,2 the Vascular Surgery In-Training Examinations (VSITE),3 the use of procedure-based assessments (PBA),4 or objective structured assessments of technical skills (OSATS).5 In addition, simulation workshops (using computer- or life-like synthetic models) play an increasing role in teaching vascular residents the ever-increasing number of different open and endovascular surgical techniques.6,7

Traditionally, the final board examination at the end of the vascular surgical training period consists of an oral assessment or a computer-based test. The obvious crucial question is whether a practical examination should be a added as a mandatory part of a vascular exit exam. This article gives an overview of the board examination of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (EBVS) at the UEMS (Union of European Medical Specialists), which adopted a technical skills assessment in 2006.

The European Vascular Surgical Examination

The UEMS was founded in 1958 as an official body of the European Union (EU). The UEMS has the remits to accredit medical meetings,8 to promote free professional movement of all doctors within Europe, and to ensure high quality of training and associated specialist standards via UEMS examinations.9,10 Currently, the UEMS represents the national medical societies of 37 member states. To date there are 42 UEMS Specialist Sections (separate and independent disciplines), UEMS Divisions (key areas within the independent disciplines, such as Interventional Radiology) and some so-called “Multidisciplinary Joint Committees” (such as Phlebology).

Since 2005, vascular surgery has been represented as an independent medical discipline within the UEMS.Politically, this was a tremendously important step that has helped many European countries to establish vascular surgery on a national level as a separate specialty. The most recent examples are Switzerland (since 2014) and Austria (since 2015).

European vascular surgical examinations have been offered since 1996. The Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery (FEBVS) is voluntary in most European countries, but in some countries, such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, the European exam has now replaced the national specialist exam.12 Other countries also are in the process of accepting this European standard as a national standard, including Romania, Austria, and Sweden.

The European exam consists of a written section and a combined oral and practical exam. Candidates must be in possession of a national specialist title for surgery or vascular surgery (in countries with a monospecialty). Applications from non-EU countries also are accepted.

Applications must be made in writing, giving details of open-operative and endovascular experience. A distinction is made between assisted operations, independently performed surgery with assistance, and actual independently performed surgical procedures without specialist tutorial assistance. All candidates admitted to the examination have to pass a one-day oral and practical examination, which includes questioning on theoretical background knowledge and its practical application. This takes place mostly in the context of specific clinical case studies as well as via practical examinations on pulsatile perfused lifelike models.

The following procedures are assessed: an infrarenal aortic anastomosis, a carotid endarterectomy, and a distal bypass anastomosis.6,13,14 In the endovascular part of the examination, the applicant’s ability to introduce a guide-wire into the renal artery is assessed.15 Unlike the case in many national tests, FEBVS candidates are also presented with a specialist English-language publication (usually from the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery). This article is then discussed with two examiners, with respect to its quality as well as its methodological content and significance. Many examination candidates fear this hurdle the most, but in fact very few participants fail this part of the test.

The European exam is designed to be unbiased and fair, with two examiners at each test station who carry out their assessments independent of each other. During the course of the examination, each candidate is interviewed by approximately 10 assessors. The assessment is validated by way of an evaluation form. The assessing auditors’ communications skills are themselves judged by observers. In the event of communication difficulties, observers are subsequently consulted.

Despite the challenging test procedures, the number of participants in the European Specialist Exam for Vascular Surgery has steadily increased in recent years. For this reason, since 2012, two examination sessions per year have been offered, one during the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) and one at the European Vascular Course (EVC) in Maastricht. The failure rate each year fluctuates around 20%.

Benefits of being a Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS)

There are a number of very good reasons to sit a European examination and acquire the title of Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS). Some of them are:

Evidence of competency in job applications. Many managers know that the European exam is theoretically and practically challenging, and comprehensive. Confidence in candidates (specialists and senior physicians) who have passed the European test is therefore higher. That in turn increases the chances of getting the desired position especially when applying abroad!

Verification of open surgical and endovascular skills. Filling in the logbook16 helps to maintain a transparent open/endovascular portfolio. It is an extremely sophisticated tool to capture expertise and experience.

Commitment to the need for a European standard. The UEMS has set itself the goal of setting a European standard for medical specialists at the highest level. The European specialist exam projects this. All FEBVS support this goal via their application.

Commitment to academic knowledge-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers theoretical background, knowledge of the main studies, basic academic skills, and the ability to comprehensively apply this knowledge to case studies from the entire vascular field. By obtaining this exam, all FEBVS confirm their commitment to an evidence-based approach to vascular surgery.

Commitment to competency-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers a practical assessment on open vascular surgical and endovascular key competencies. By passing this part of the exam, all FEBVS give evidence that they are technically competent vascular surgeons.

Desire to belong to the best of the profession. The European specialist exam is certainly more demanding than many national board certifications. However, it offers an opportunity to belong to the European vascular surgical elite.

In conclusion, the European experience on board examinations including skills assessment shows pretty clearly that this sort of comprehensive examination is feasible. Moreover, the increasing number of applications indicates the growing attractiveness of the European certification and qualification as FEBVS. The long-term goal will be to make this examination mandatory for all EU countries – still a long way to go. By the way, since the status of FEBVS is also achievable by non-EU countries, Brexit will not prevent vascular surgeons from the United Kingdom to qualify as FEBVS in the future!

Dr. Eckstein is the Past President of the Board and Section of Vascular Surgery at the Union of European Medical Specialists (UEMS) and Past President of the German Vascular Society (DGG), and an associate editor for Vascular Specialist.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:945-49

2. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1140-6

3. Vascular surgery qualifying examination and Vsite

4. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:i-xxi, 1-162

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1422-8

8. International Angiology. 2007;26:361-6

9. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:109-15

10. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:69S-75S; discussion 75S

12. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:719-25

13. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1148-54

14. Brit J Surg. 2006;93:1132-8

The incidence of vascular diseases is steadily increasing because of an aging population. Vascular surgery is the only specialty that can offer all modalities of vascular therapy (endovascular, open, and conservative). It is therefore necessary to ensure implementation of all these modalities in a modern vascular surgical curricula. The creation of a vascular specialist curriculum is undoubtedly the best way to overcome further fragmentation of vascular provision and to prevent the increasingly financially-driven incentives that can mislead treatment. For obvious reasons this would be a major benefit for our patients and for our specialty.

Another reason for updating the vascular surgical curricula is the significant reduction of open aortic and peripheral vascular surgical training cases, such as abdominal aortic aneurysms and superficial femoral artery occlusions.1 Since the vast majority of these patients are now treated by endovascular means, the remaining vascular disease morphologies can technically be very demanding when requiring open vascular surgery procedures.

Nevertheless, the public and our patients quite understandably expect to be treated by well trained and competent vascular surgeons/specialists. As in all other professions, a proper assessment of all vascular competencies is therefore considered to be mandatory at the end of the training period for a vascular specialist. To this end, several proposals have been made to improve both the structure and different assessment tools including the Vascular Surgical Milestones Project,2 the Vascular Surgery In-Training Examinations (VSITE),3 the use of procedure-based assessments (PBA),4 or objective structured assessments of technical skills (OSATS).5 In addition, simulation workshops (using computer- or life-like synthetic models) play an increasing role in teaching vascular residents the ever-increasing number of different open and endovascular surgical techniques.6,7

Traditionally, the final board examination at the end of the vascular surgical training period consists of an oral assessment or a computer-based test. The obvious crucial question is whether a practical examination should be a added as a mandatory part of a vascular exit exam. This article gives an overview of the board examination of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (EBVS) at the UEMS (Union of European Medical Specialists), which adopted a technical skills assessment in 2006.

The European Vascular Surgical Examination

The UEMS was founded in 1958 as an official body of the European Union (EU). The UEMS has the remits to accredit medical meetings,8 to promote free professional movement of all doctors within Europe, and to ensure high quality of training and associated specialist standards via UEMS examinations.9,10 Currently, the UEMS represents the national medical societies of 37 member states. To date there are 42 UEMS Specialist Sections (separate and independent disciplines), UEMS Divisions (key areas within the independent disciplines, such as Interventional Radiology) and some so-called “Multidisciplinary Joint Committees” (such as Phlebology).

Since 2005, vascular surgery has been represented as an independent medical discipline within the UEMS.Politically, this was a tremendously important step that has helped many European countries to establish vascular surgery on a national level as a separate specialty. The most recent examples are Switzerland (since 2014) and Austria (since 2015).

European vascular surgical examinations have been offered since 1996. The Fellowship of the European Board in Vascular Surgery (FEBVS) is voluntary in most European countries, but in some countries, such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, the European exam has now replaced the national specialist exam.12 Other countries also are in the process of accepting this European standard as a national standard, including Romania, Austria, and Sweden.

The European exam consists of a written section and a combined oral and practical exam. Candidates must be in possession of a national specialist title for surgery or vascular surgery (in countries with a monospecialty). Applications from non-EU countries also are accepted.

Applications must be made in writing, giving details of open-operative and endovascular experience. A distinction is made between assisted operations, independently performed surgery with assistance, and actual independently performed surgical procedures without specialist tutorial assistance. All candidates admitted to the examination have to pass a one-day oral and practical examination, which includes questioning on theoretical background knowledge and its practical application. This takes place mostly in the context of specific clinical case studies as well as via practical examinations on pulsatile perfused lifelike models.

The following procedures are assessed: an infrarenal aortic anastomosis, a carotid endarterectomy, and a distal bypass anastomosis.6,13,14 In the endovascular part of the examination, the applicant’s ability to introduce a guide-wire into the renal artery is assessed.15 Unlike the case in many national tests, FEBVS candidates are also presented with a specialist English-language publication (usually from the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery). This article is then discussed with two examiners, with respect to its quality as well as its methodological content and significance. Many examination candidates fear this hurdle the most, but in fact very few participants fail this part of the test.

The European exam is designed to be unbiased and fair, with two examiners at each test station who carry out their assessments independent of each other. During the course of the examination, each candidate is interviewed by approximately 10 assessors. The assessment is validated by way of an evaluation form. The assessing auditors’ communications skills are themselves judged by observers. In the event of communication difficulties, observers are subsequently consulted.

Despite the challenging test procedures, the number of participants in the European Specialist Exam for Vascular Surgery has steadily increased in recent years. For this reason, since 2012, two examination sessions per year have been offered, one during the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) and one at the European Vascular Course (EVC) in Maastricht. The failure rate each year fluctuates around 20%.

Benefits of being a Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS)

There are a number of very good reasons to sit a European examination and acquire the title of Fellow of the European Board of Vascular Surgery (FEBVS). Some of them are:

Evidence of competency in job applications. Many managers know that the European exam is theoretically and practically challenging, and comprehensive. Confidence in candidates (specialists and senior physicians) who have passed the European test is therefore higher. That in turn increases the chances of getting the desired position especially when applying abroad!

Verification of open surgical and endovascular skills. Filling in the logbook16 helps to maintain a transparent open/endovascular portfolio. It is an extremely sophisticated tool to capture expertise and experience.

Commitment to the need for a European standard. The UEMS has set itself the goal of setting a European standard for medical specialists at the highest level. The European specialist exam projects this. All FEBVS support this goal via their application.

Commitment to academic knowledge-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers theoretical background, knowledge of the main studies, basic academic skills, and the ability to comprehensively apply this knowledge to case studies from the entire vascular field. By obtaining this exam, all FEBVS confirm their commitment to an evidence-based approach to vascular surgery.

Commitment to competency-based vascular surgery. The European Vascular Surgery specialist exam covers a practical assessment on open vascular surgical and endovascular key competencies. By passing this part of the exam, all FEBVS give evidence that they are technically competent vascular surgeons.

Desire to belong to the best of the profession. The European specialist exam is certainly more demanding than many national board certifications. However, it offers an opportunity to belong to the European vascular surgical elite.

In conclusion, the European experience on board examinations including skills assessment shows pretty clearly that this sort of comprehensive examination is feasible. Moreover, the increasing number of applications indicates the growing attractiveness of the European certification and qualification as FEBVS. The long-term goal will be to make this examination mandatory for all EU countries – still a long way to go. By the way, since the status of FEBVS is also achievable by non-EU countries, Brexit will not prevent vascular surgeons from the United Kingdom to qualify as FEBVS in the future!

Dr. Eckstein is the Past President of the Board and Section of Vascular Surgery at the Union of European Medical Specialists (UEMS) and Past President of the German Vascular Society (DGG), and an associate editor for Vascular Specialist.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:945-49

2. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1140-6

3. Vascular surgery qualifying examination and Vsite

4. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:i-xxi, 1-162

6. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1422-8

8. International Angiology. 2007;26:361-6

9. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:109-15

10. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:69S-75S; discussion 75S

12. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:719-25

13. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1148-54

14. Brit J Surg. 2006;93:1132-8

Does congenital cardiac surgery training need a makeover?

Trainees in congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs are doing more operations since the programs became accredited in 2007, but no clear parameters have emerged to determine if certification has improved the quality of training, according to an evaluation of fellowship training programs published in the June issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Jun;151:1488-95).

Overall, the training has become standardized, the fellows’ operative experience is “robust,” and fellows are mostly satisfied since the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognized congenital cardiac surgery as a fellowship in 2007, lead study author Dr. Brian Kogon of Emory University, Atlanta, said.

However, Dr. Kogon and his colleagues also found some shortcomings in fellowship training. They received survey responses from 36 of 44 fellows in 12 accredited programs nationwide. To determine if fellows were meeting minimum case requirements, they also reviewed operative logs of 38 of the 44 fellows. They compared their findings to a study of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs they did pre-ACGME accreditation (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006 Dec;132:1280). “The number of operations performed by the fellows during their training was underwhelming, and most of the fellows were dissatisfied with their operative experience,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote in the earlier study.

The study found that all fellows achieved the minimum number of 75 total cases the standards require for graduation, with a median of 136; and the minimum standard of 36 specific qualifying cases with a median of 63. However, seven did not meet the minimum of five complex neonate cases. Among other types of operations for which fellows failed to meet the minimum cases were atrioventricular septal defect repair, arch reconstruction including coarctation procedures and systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt procedures.

The comparative lack of adult cardiac surgery operations was also considered a potential problem, the authors noted, pointing out that “the number of adults who have congenital heart disease now exceeds the number of children who have the disease, and many of these patients will require an operation.”

Another shortcoming the study found was a drop-off in international fellowships since 2007. “This change places us at risk of becoming intellectually isolated and losing international relationships that are critical to the future of our specialty,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote. Graduated fellows also acknowledged dissatisfaction with their lack of exposure to neonate surgery.

The study also determined the following demographics of the fellows: 83% are men and the median age at graduation was 40 years, with a range of 35-48 years. Only 25% of graduates participated in nonsurgical rotations such as cardiac catheterization and echocardiography.

“Although the operative experience seems to be much more robust, and this finding has been corroborated in other surgical disciplines after the advent of ACGME accreditation, comparing training before and after the accreditation process came into existence is difficult,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

The study also noted that the Thoracic Surgery Directors Association developed a congenital curriculum for congenital cardiothoracic surgery fellows, but only 28% used that curriculum and only 61% used any formal curriculum. “Unfortunately, regardless of the curriculum, only 50% of the graduates found it helpful,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

And regardless of the curriculum, only half of the graduates have passed the written qualifying and oral certifying examinations after completing their fellowship. “Although the curriculum is quite robust, the latter statistic suggests that we need either more emphasis on education by the program directors or a better and/or different curriculum,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said. However, they added that “after training, former fellows have adequate case volumes and mixes and seem to be thriving in the field.”

Dr. Kogon and his study coauthors had no financial disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Charles D. Fraser Jr. of Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor University, Houston, called the study findings that only 50% of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship graduates had passed the congenital examination “quite disturbing” and the demographic data and surgical and nonsurgical experience of the trainees “thought provoking” (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1496-7)

“Is the bar too high or too low?” Dr. Fraser asked. He suggested the fellowship training system for congenital cardiac surgeons may be a work in progress. “For one, having a median age of 40 years for graduates is unacceptable,” he said. For half of trainees to not pass the examination “at this advanced age is tragic.” That 25% of fellows participate in nonsurgical rotations “also is concerning.”

|

Dr. Charles D. Fraser |

A challenge is that after fellows complete their training in general and cardiothoracic surgery, opportunities to operate on newborns in a new fellowship setting are extremely limited, Dr. Fraser said. “To expect someone to be able to perform complex newborn heart surgery with excellent outcomes in a brand-new environment after just learning how to perform adult cardiac surgery is unrealistic,” he said.

Dr. Fraser said 1 formal year of training for congenital cardiac surgery fellows may not be enough. “Our colleagues in general pediatric surgery have a 2-year fellowship, and our specialty is every bit as complex as theirs,” he said. The basic American Board of Thoracic Surgery thoracic fellowship should have more latitude in its congenital heart surgery rotations, including exposure to pediatrics, neonatal/pediatric critical care, and the nonsurgical rotations the study referred to. Congenital heart surgery fellowships should also embrace adult congenital heart surgery with a more formalized experience requirement, he said.

“As a specialty, we owe it to our fine young surgeon candidates to offer the most robust and fair pathway to success while never compromising on the public trust and patient well-being,” Dr. Fraser said.

Dr. Fraser is chief of the division of congenital heart surgery at Baylor and codirector of the Texas Children’s Heart Center. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Charles D. Fraser Jr. of Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor University, Houston, called the study findings that only 50% of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship graduates had passed the congenital examination “quite disturbing” and the demographic data and surgical and nonsurgical experience of the trainees “thought provoking” (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1496-7)

“Is the bar too high or too low?” Dr. Fraser asked. He suggested the fellowship training system for congenital cardiac surgeons may be a work in progress. “For one, having a median age of 40 years for graduates is unacceptable,” he said. For half of trainees to not pass the examination “at this advanced age is tragic.” That 25% of fellows participate in nonsurgical rotations “also is concerning.”

|

Dr. Charles D. Fraser |

A challenge is that after fellows complete their training in general and cardiothoracic surgery, opportunities to operate on newborns in a new fellowship setting are extremely limited, Dr. Fraser said. “To expect someone to be able to perform complex newborn heart surgery with excellent outcomes in a brand-new environment after just learning how to perform adult cardiac surgery is unrealistic,” he said.

Dr. Fraser said 1 formal year of training for congenital cardiac surgery fellows may not be enough. “Our colleagues in general pediatric surgery have a 2-year fellowship, and our specialty is every bit as complex as theirs,” he said. The basic American Board of Thoracic Surgery thoracic fellowship should have more latitude in its congenital heart surgery rotations, including exposure to pediatrics, neonatal/pediatric critical care, and the nonsurgical rotations the study referred to. Congenital heart surgery fellowships should also embrace adult congenital heart surgery with a more formalized experience requirement, he said.

“As a specialty, we owe it to our fine young surgeon candidates to offer the most robust and fair pathway to success while never compromising on the public trust and patient well-being,” Dr. Fraser said.

Dr. Fraser is chief of the division of congenital heart surgery at Baylor and codirector of the Texas Children’s Heart Center. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Charles D. Fraser Jr. of Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor University, Houston, called the study findings that only 50% of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship graduates had passed the congenital examination “quite disturbing” and the demographic data and surgical and nonsurgical experience of the trainees “thought provoking” (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1496-7)

“Is the bar too high or too low?” Dr. Fraser asked. He suggested the fellowship training system for congenital cardiac surgeons may be a work in progress. “For one, having a median age of 40 years for graduates is unacceptable,” he said. For half of trainees to not pass the examination “at this advanced age is tragic.” That 25% of fellows participate in nonsurgical rotations “also is concerning.”

|

Dr. Charles D. Fraser |

A challenge is that after fellows complete their training in general and cardiothoracic surgery, opportunities to operate on newborns in a new fellowship setting are extremely limited, Dr. Fraser said. “To expect someone to be able to perform complex newborn heart surgery with excellent outcomes in a brand-new environment after just learning how to perform adult cardiac surgery is unrealistic,” he said.

Dr. Fraser said 1 formal year of training for congenital cardiac surgery fellows may not be enough. “Our colleagues in general pediatric surgery have a 2-year fellowship, and our specialty is every bit as complex as theirs,” he said. The basic American Board of Thoracic Surgery thoracic fellowship should have more latitude in its congenital heart surgery rotations, including exposure to pediatrics, neonatal/pediatric critical care, and the nonsurgical rotations the study referred to. Congenital heart surgery fellowships should also embrace adult congenital heart surgery with a more formalized experience requirement, he said.

“As a specialty, we owe it to our fine young surgeon candidates to offer the most robust and fair pathway to success while never compromising on the public trust and patient well-being,” Dr. Fraser said.

Dr. Fraser is chief of the division of congenital heart surgery at Baylor and codirector of the Texas Children’s Heart Center. He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Trainees in congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs are doing more operations since the programs became accredited in 2007, but no clear parameters have emerged to determine if certification has improved the quality of training, according to an evaluation of fellowship training programs published in the June issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Jun;151:1488-95).

Overall, the training has become standardized, the fellows’ operative experience is “robust,” and fellows are mostly satisfied since the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognized congenital cardiac surgery as a fellowship in 2007, lead study author Dr. Brian Kogon of Emory University, Atlanta, said.

However, Dr. Kogon and his colleagues also found some shortcomings in fellowship training. They received survey responses from 36 of 44 fellows in 12 accredited programs nationwide. To determine if fellows were meeting minimum case requirements, they also reviewed operative logs of 38 of the 44 fellows. They compared their findings to a study of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs they did pre-ACGME accreditation (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006 Dec;132:1280). “The number of operations performed by the fellows during their training was underwhelming, and most of the fellows were dissatisfied with their operative experience,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote in the earlier study.

The study found that all fellows achieved the minimum number of 75 total cases the standards require for graduation, with a median of 136; and the minimum standard of 36 specific qualifying cases with a median of 63. However, seven did not meet the minimum of five complex neonate cases. Among other types of operations for which fellows failed to meet the minimum cases were atrioventricular septal defect repair, arch reconstruction including coarctation procedures and systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt procedures.

The comparative lack of adult cardiac surgery operations was also considered a potential problem, the authors noted, pointing out that “the number of adults who have congenital heart disease now exceeds the number of children who have the disease, and many of these patients will require an operation.”

Another shortcoming the study found was a drop-off in international fellowships since 2007. “This change places us at risk of becoming intellectually isolated and losing international relationships that are critical to the future of our specialty,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote. Graduated fellows also acknowledged dissatisfaction with their lack of exposure to neonate surgery.

The study also determined the following demographics of the fellows: 83% are men and the median age at graduation was 40 years, with a range of 35-48 years. Only 25% of graduates participated in nonsurgical rotations such as cardiac catheterization and echocardiography.

“Although the operative experience seems to be much more robust, and this finding has been corroborated in other surgical disciplines after the advent of ACGME accreditation, comparing training before and after the accreditation process came into existence is difficult,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

The study also noted that the Thoracic Surgery Directors Association developed a congenital curriculum for congenital cardiothoracic surgery fellows, but only 28% used that curriculum and only 61% used any formal curriculum. “Unfortunately, regardless of the curriculum, only 50% of the graduates found it helpful,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

And regardless of the curriculum, only half of the graduates have passed the written qualifying and oral certifying examinations after completing their fellowship. “Although the curriculum is quite robust, the latter statistic suggests that we need either more emphasis on education by the program directors or a better and/or different curriculum,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said. However, they added that “after training, former fellows have adequate case volumes and mixes and seem to be thriving in the field.”

Dr. Kogon and his study coauthors had no financial disclosures.

Trainees in congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs are doing more operations since the programs became accredited in 2007, but no clear parameters have emerged to determine if certification has improved the quality of training, according to an evaluation of fellowship training programs published in the June issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Jun;151:1488-95).

Overall, the training has become standardized, the fellows’ operative experience is “robust,” and fellows are mostly satisfied since the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recognized congenital cardiac surgery as a fellowship in 2007, lead study author Dr. Brian Kogon of Emory University, Atlanta, said.

However, Dr. Kogon and his colleagues also found some shortcomings in fellowship training. They received survey responses from 36 of 44 fellows in 12 accredited programs nationwide. To determine if fellows were meeting minimum case requirements, they also reviewed operative logs of 38 of the 44 fellows. They compared their findings to a study of congenital cardiac surgery fellowship programs they did pre-ACGME accreditation (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006 Dec;132:1280). “The number of operations performed by the fellows during their training was underwhelming, and most of the fellows were dissatisfied with their operative experience,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote in the earlier study.

The study found that all fellows achieved the minimum number of 75 total cases the standards require for graduation, with a median of 136; and the minimum standard of 36 specific qualifying cases with a median of 63. However, seven did not meet the minimum of five complex neonate cases. Among other types of operations for which fellows failed to meet the minimum cases were atrioventricular septal defect repair, arch reconstruction including coarctation procedures and systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt procedures.

The comparative lack of adult cardiac surgery operations was also considered a potential problem, the authors noted, pointing out that “the number of adults who have congenital heart disease now exceeds the number of children who have the disease, and many of these patients will require an operation.”

Another shortcoming the study found was a drop-off in international fellowships since 2007. “This change places us at risk of becoming intellectually isolated and losing international relationships that are critical to the future of our specialty,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues wrote. Graduated fellows also acknowledged dissatisfaction with their lack of exposure to neonate surgery.

The study also determined the following demographics of the fellows: 83% are men and the median age at graduation was 40 years, with a range of 35-48 years. Only 25% of graduates participated in nonsurgical rotations such as cardiac catheterization and echocardiography.

“Although the operative experience seems to be much more robust, and this finding has been corroborated in other surgical disciplines after the advent of ACGME accreditation, comparing training before and after the accreditation process came into existence is difficult,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

The study also noted that the Thoracic Surgery Directors Association developed a congenital curriculum for congenital cardiothoracic surgery fellows, but only 28% used that curriculum and only 61% used any formal curriculum. “Unfortunately, regardless of the curriculum, only 50% of the graduates found it helpful,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said.

And regardless of the curriculum, only half of the graduates have passed the written qualifying and oral certifying examinations after completing their fellowship. “Although the curriculum is quite robust, the latter statistic suggests that we need either more emphasis on education by the program directors or a better and/or different curriculum,” Dr. Kogon and his colleagues said. However, they added that “after training, former fellows have adequate case volumes and mixes and seem to be thriving in the field.”

Dr. Kogon and his study coauthors had no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Since congenital cardiac fellowship programs became accredited in 2007, training requirements have been standardized and the surgical experience robust.

Major finding: Recent graduates of fellowship programs are thriving in practice, but shortcomings with existing fellowship training exist, including only 50% gaining certification by passing the written and oral exams.

Data source: The study drew on survey responses from 36 of 44 fellows in 12 accredited programs and a review of operative logs of 38 of the 44 fellows.

Disclosures: Dr. Kogon and his study coauthors had no financial disclosures.

General surgeons getting less vascular training

Vascular surgery fellow case logs reflect an increase in endovascular interventions, but general surgery residents may be missing out on training opportunities, according to a study of national case data.

In addition, general surgery residents saw a decrease in open vascular surgery cases, which was not reflected among the vascular surgery fellows, according to Dr. Rose C. Pedersen and colleagues in the department of surgery, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. The report was published online in Annals of Vascular Surgery (doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.02.008).

The paper was originally presented at the 2105 annual meeting of the Southern California Vascular Society. The study reports findings of a review of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education national case log reports from 2001 to 2012.