User login

Few, if any, vascular specialists are aggressively treating massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at community hospitals, but it is feasible and can have good outcomes with proper planning and preparation, according to Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism (PE) can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function, he said. However, catheter-directed interventions for these patients is rare outside of academic or tertiary-care settings, probably because of a lack of randomized trials, little retrospective data, and lack of expertise, he said.

For physicians considering this treatment at their own community hospitals, Dr. Wang emphasized that preparing the hospital and protocols are as important as is technical expertise in doing the procedure. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis, for example.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," said Dr. Wang of Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, Rockville, Md.

Before doing his first case, he made sure that protocols were in place in the emergency department, in the ICU, and with the hospitalist team for the early detection of deep vein thrombosis and PE, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients.

Systemic anticoagulation has been the mainstay of treatment for PE, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians have recommended more aggressive therapy for massive and submassive PEs, Dr. Wang said. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour of embolism formation. Within 30 days of submassive PE formation, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale.

Approximately 30% of all 500,000 symptomatic PEs diagnosed each year in the United States lead to death. Even among inpatients who are diagnosed with a PE while in the hospital, the mortality rate is approximately 10%-15%, he said.

Until recently, there was no Food and Drug Administration–approved device for catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. "There’s also not a purpose-built device to help you with these types of procedures," Dr. Wang said.

At the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, he described treating nine women and three men who had a total of seven massive and five submassive PEs. Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was offered to patients with massive or submassive PE if they were hemodynamically unstable or had right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin levels, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mm Hg, or if they were not being weaned off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excluded patients who were actively bleeding or who were not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation – "not even aspirin," he said.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor. "Typically those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big PE, and the orthopedist would give him the green light for aggressive treatment.

All procedures were technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure, and there were no bleeding events.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely due to a paradoxical embolism to the intestine, Dr. Wang said. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention.

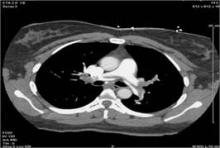

His technique includes accessing the internal jugular vein to get to the pulmonary artery, placing a vena cava filter, and giving tissue plasminogen activator as the lytic agent. All patients had a spiral CT scan before going to the catheterization lab, so pulmonary angiography was not routinely performed.

He reserved mechanical (catheter) thrombectomy for some patients with massive thromboembolism. Instead of being guided by angiography, he determined the duration of mechanical thrombectomy by the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

"I discontinued mechanical thrombectomy once oxygen saturation was above 95%, they’re weaning off their inotropes, and the pulse rate was trending toward normal," he said.

For some patients who developed nonsinus arrhythmias due to the wire manipulations within the heart and pulmonary arteries, he removed the wire device, waited for it to resolve, and continued. A minority of patients whose arrhythmias continued to occur during the intervention received calcium blockade or beta blockade.

Patients who received mechanical thrombectomy developed dark or bloody urine that resolved within 48 hours with hydration.

Follow-up at 2 weeks assessed general function and access sites, and patients had a repeat echocardiogram at 1 month. If they were doing well functionally and pulmonary hypertension had resolved, Dr. Wang offered to remove the vena cava filter. All but one patient accepted. All were to remain on systemic anticoagulation for 6-12 months, and patients with massive PE underwent hematologic workups.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

It amazes me that over many decades, the treatment of pulmonary embolism has remained stagnant. There have been no significant changes in the way we treat these patients. Most are treated with systemic anticoagulation and prolonged warfarin therapy.

There are many limitations to the use of systemic thrombolysis. The most important one is a high incidence of bleeding complications, about 20%-40%. Surgical thrombectomy also has limitations and is performed in a very limited number of centers, with mortality rates of about 10%-20%.

There is no question in my mind that there is a large potential benefit in treating patients with catheter-directed thrombolysis, particularly patients with massive pulmonary embolism. There’s also a potential benefit from catheter-directed thrombolysis in a large subgroup of patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. Those patients may benefit the most in terms of prevention of pulmonary hypertension.

Many of these questions are being investigated now in a European prospective, randomized trial comparing catheter-guided pulmonary thrombolysis to chemical thrombolysis. In the Unites States, there are a couple of registries for these patients, and a randomized trial is expected to start in the near future. I encourage vascular specialists to enroll patients in these.

Dr. Juan Ayerdi is a clinical assistant professor of vascular surgery at the Medical Center of Central Georgia, Macon. He made these remarks as the discussant of Dr. Wang’s presentation at the meeting. Dr. Ayerdi reported having no financial disclosures.

Few, if any, vascular specialists are aggressively treating massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at community hospitals, but it is feasible and can have good outcomes with proper planning and preparation, according to Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism (PE) can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function, he said. However, catheter-directed interventions for these patients is rare outside of academic or tertiary-care settings, probably because of a lack of randomized trials, little retrospective data, and lack of expertise, he said.

For physicians considering this treatment at their own community hospitals, Dr. Wang emphasized that preparing the hospital and protocols are as important as is technical expertise in doing the procedure. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis, for example.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," said Dr. Wang of Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, Rockville, Md.

Before doing his first case, he made sure that protocols were in place in the emergency department, in the ICU, and with the hospitalist team for the early detection of deep vein thrombosis and PE, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients.

Systemic anticoagulation has been the mainstay of treatment for PE, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians have recommended more aggressive therapy for massive and submassive PEs, Dr. Wang said. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour of embolism formation. Within 30 days of submassive PE formation, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale.

Approximately 30% of all 500,000 symptomatic PEs diagnosed each year in the United States lead to death. Even among inpatients who are diagnosed with a PE while in the hospital, the mortality rate is approximately 10%-15%, he said.

Until recently, there was no Food and Drug Administration–approved device for catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. "There’s also not a purpose-built device to help you with these types of procedures," Dr. Wang said.

At the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, he described treating nine women and three men who had a total of seven massive and five submassive PEs. Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was offered to patients with massive or submassive PE if they were hemodynamically unstable or had right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin levels, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mm Hg, or if they were not being weaned off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excluded patients who were actively bleeding or who were not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation – "not even aspirin," he said.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor. "Typically those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big PE, and the orthopedist would give him the green light for aggressive treatment.

All procedures were technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure, and there were no bleeding events.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely due to a paradoxical embolism to the intestine, Dr. Wang said. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention.

His technique includes accessing the internal jugular vein to get to the pulmonary artery, placing a vena cava filter, and giving tissue plasminogen activator as the lytic agent. All patients had a spiral CT scan before going to the catheterization lab, so pulmonary angiography was not routinely performed.

He reserved mechanical (catheter) thrombectomy for some patients with massive thromboembolism. Instead of being guided by angiography, he determined the duration of mechanical thrombectomy by the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

"I discontinued mechanical thrombectomy once oxygen saturation was above 95%, they’re weaning off their inotropes, and the pulse rate was trending toward normal," he said.

For some patients who developed nonsinus arrhythmias due to the wire manipulations within the heart and pulmonary arteries, he removed the wire device, waited for it to resolve, and continued. A minority of patients whose arrhythmias continued to occur during the intervention received calcium blockade or beta blockade.

Patients who received mechanical thrombectomy developed dark or bloody urine that resolved within 48 hours with hydration.

Follow-up at 2 weeks assessed general function and access sites, and patients had a repeat echocardiogram at 1 month. If they were doing well functionally and pulmonary hypertension had resolved, Dr. Wang offered to remove the vena cava filter. All but one patient accepted. All were to remain on systemic anticoagulation for 6-12 months, and patients with massive PE underwent hematologic workups.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

Few, if any, vascular specialists are aggressively treating massive or submassive pulmonary embolism with catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at community hospitals, but it is feasible and can have good outcomes with proper planning and preparation, according to Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism (PE) can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function, he said. However, catheter-directed interventions for these patients is rare outside of academic or tertiary-care settings, probably because of a lack of randomized trials, little retrospective data, and lack of expertise, he said.

For physicians considering this treatment at their own community hospitals, Dr. Wang emphasized that preparing the hospital and protocols are as important as is technical expertise in doing the procedure. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis, for example.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," said Dr. Wang of Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, Rockville, Md.

Before doing his first case, he made sure that protocols were in place in the emergency department, in the ICU, and with the hospitalist team for the early detection of deep vein thrombosis and PE, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients.

Systemic anticoagulation has been the mainstay of treatment for PE, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians have recommended more aggressive therapy for massive and submassive PEs, Dr. Wang said. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour of embolism formation. Within 30 days of submassive PE formation, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale.

Approximately 30% of all 500,000 symptomatic PEs diagnosed each year in the United States lead to death. Even among inpatients who are diagnosed with a PE while in the hospital, the mortality rate is approximately 10%-15%, he said.

Until recently, there was no Food and Drug Administration–approved device for catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. "There’s also not a purpose-built device to help you with these types of procedures," Dr. Wang said.

At the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, he described treating nine women and three men who had a total of seven massive and five submassive PEs. Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy was offered to patients with massive or submassive PE if they were hemodynamically unstable or had right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin levels, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mm Hg, or if they were not being weaned off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excluded patients who were actively bleeding or who were not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation – "not even aspirin," he said.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor. "Typically those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big PE, and the orthopedist would give him the green light for aggressive treatment.

All procedures were technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure, and there were no bleeding events.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely due to a paradoxical embolism to the intestine, Dr. Wang said. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention.

His technique includes accessing the internal jugular vein to get to the pulmonary artery, placing a vena cava filter, and giving tissue plasminogen activator as the lytic agent. All patients had a spiral CT scan before going to the catheterization lab, so pulmonary angiography was not routinely performed.

He reserved mechanical (catheter) thrombectomy for some patients with massive thromboembolism. Instead of being guided by angiography, he determined the duration of mechanical thrombectomy by the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

"I discontinued mechanical thrombectomy once oxygen saturation was above 95%, they’re weaning off their inotropes, and the pulse rate was trending toward normal," he said.

For some patients who developed nonsinus arrhythmias due to the wire manipulations within the heart and pulmonary arteries, he removed the wire device, waited for it to resolve, and continued. A minority of patients whose arrhythmias continued to occur during the intervention received calcium blockade or beta blockade.

Patients who received mechanical thrombectomy developed dark or bloody urine that resolved within 48 hours with hydration.

Follow-up at 2 weeks assessed general function and access sites, and patients had a repeat echocardiogram at 1 month. If they were doing well functionally and pulmonary hypertension had resolved, Dr. Wang offered to remove the vena cava filter. All but one patient accepted. All were to remain on systemic anticoagulation for 6-12 months, and patients with massive PE underwent hematologic workups.

Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.