User login

Community Hospital Offers Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis

With the advantage of around-the-clock hospitalist services, one community hospital has been able to offer catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy – a procedure typically available only at tertiary-care hospitals.

Dr. Brian A. Carpenter, medical director of the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Md., said that at least 12 patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolisms have undergone catheter-directed thrombolysis at the hospital. Many others have undergone the procedure for deep vein thrombosis in a lower extremity with vascular extension into the larger vessels of the pelvis.

Before the service was introduced, patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism were sent to a tertiary-care hospital if they were stable enough for transfer. Otherwise, they were monitored in the ICU, managed medically with systemic anticoagulation, and transferred later if they still needed further treatment.

Systemic anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary embolism, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend a more aggressive approach for massive and submassive PE. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour after the embolus forms. Within 30 days after submassive PE, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale, according to a data presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

The catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at Shady Grove Adventist largely owes its success to a vascular surgeon who took the lead in establishing protocols and training support staff, with hospitalists as a key part of the team.

The vascular surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang, reported on the outcomes of the first 12 patients, in whom the procedures were all technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all patients were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure. There were no bleeding complications.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely because of a paradoxical embolus to the intestine. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention, according to Dr. Wang of Horizon Vascular Specialists. The group contracts to provide vascular surgical care at Shady Grove Adventist and two other hospitals in Maryland.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function in patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism, Dr. Wang said. Patients with massive or submassive PE are offered catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy if they are hemodynamically unstable; if they have right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mmHg; or if they are not weaning off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excludes patients who are actively bleeding or who are not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor in his case series. "Typically, those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big pulmonary embolus, and the orthopedist would give a green light for aggressive treatment.

But most of the patients who have received catheter-directed thrombolytic procedures presented to the emergency department with lower extremity swelling, and were found on sonography to have a thrombus extending into the large pelvic vessels. Dr. Carpenter’s service admits approximately 90% of adult inpatients, so the hospitalists usually are the ones to determine which patients should be considered for the interventional approach and which ones get medical therapy.

Dr. Wang emphasized that the protocols are as important as technical expertise in catheter-directed thrombolysis. Protocols are in place for the ED, the ICU, and the hospitalist team for the early detection of DVT and pulmonary emboli, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients. Dr. Wang also took the lead on the anticoagulation aspect of computerized physician order entry.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," Dr. Wang said. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis.

"It’s amazing to see such a dramatic improvement in patient symptoms almost immediately post procedure," said Dr. Carpenter.

Patients who undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis require close postoperative monitoring, said Dr. Carpenter, who is with Inpatient Specialists, a group that contracts with hospitals to provide hospitalist services. The main risks are bleeding, low blood pressure, or respiratory distress. "The bleeding might not necessarily be obvious," as the antithrombotic agent is given locally and bleeding can be local as well.

Community hospitals that offer catheter-directed thrombolysis need sufficient commitment from vascular surgeons and robust postprocedure support, Dr. Carpenter said. The vascular surgery group should be able to offer the procedure to all patients who need it.

Around-the-clock hospitalist availability is a good idea, especially if the surgeon is not on the in-house staff. "Don’t do [this procedure] if the hospitalist is providing triage services at night," he advised.

With 23 full-time positions (translating into 40 full-time or part-time physicians), the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist, a 339-bed hospital, typically provides 10 hospitalists during weekdays (including one medical-psychiatric physician) and 8 on weekend days.

Besides the adult hospitalist group, the hospital has a pediatric hospitalist service, 24-hour in-house ICU hospitalist coverage, and a surgical hospitalist group. "Not many hospitals have surgical hospitalists," Dr. Carpenter noted. Laborists also are available 24 hours a day for in-house ob.gyn. consultations.

Dr. Carpenter, who has been a hospitalist since 2006, said that this "is how hospital-based medicine is progressing. "Shady Grove has been an early adopter" of expanded hospitalist services.

Dr. Carpenter and Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

With the advantage of around-the-clock hospitalist services, one community hospital has been able to offer catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy – a procedure typically available only at tertiary-care hospitals.

Dr. Brian A. Carpenter, medical director of the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Md., said that at least 12 patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolisms have undergone catheter-directed thrombolysis at the hospital. Many others have undergone the procedure for deep vein thrombosis in a lower extremity with vascular extension into the larger vessels of the pelvis.

Before the service was introduced, patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism were sent to a tertiary-care hospital if they were stable enough for transfer. Otherwise, they were monitored in the ICU, managed medically with systemic anticoagulation, and transferred later if they still needed further treatment.

Systemic anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary embolism, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend a more aggressive approach for massive and submassive PE. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour after the embolus forms. Within 30 days after submassive PE, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale, according to a data presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

The catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at Shady Grove Adventist largely owes its success to a vascular surgeon who took the lead in establishing protocols and training support staff, with hospitalists as a key part of the team.

The vascular surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang, reported on the outcomes of the first 12 patients, in whom the procedures were all technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all patients were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure. There were no bleeding complications.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely because of a paradoxical embolus to the intestine. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention, according to Dr. Wang of Horizon Vascular Specialists. The group contracts to provide vascular surgical care at Shady Grove Adventist and two other hospitals in Maryland.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function in patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism, Dr. Wang said. Patients with massive or submassive PE are offered catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy if they are hemodynamically unstable; if they have right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mmHg; or if they are not weaning off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excludes patients who are actively bleeding or who are not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor in his case series. "Typically, those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big pulmonary embolus, and the orthopedist would give a green light for aggressive treatment.

But most of the patients who have received catheter-directed thrombolytic procedures presented to the emergency department with lower extremity swelling, and were found on sonography to have a thrombus extending into the large pelvic vessels. Dr. Carpenter’s service admits approximately 90% of adult inpatients, so the hospitalists usually are the ones to determine which patients should be considered for the interventional approach and which ones get medical therapy.

Dr. Wang emphasized that the protocols are as important as technical expertise in catheter-directed thrombolysis. Protocols are in place for the ED, the ICU, and the hospitalist team for the early detection of DVT and pulmonary emboli, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients. Dr. Wang also took the lead on the anticoagulation aspect of computerized physician order entry.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," Dr. Wang said. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis.

"It’s amazing to see such a dramatic improvement in patient symptoms almost immediately post procedure," said Dr. Carpenter.

Patients who undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis require close postoperative monitoring, said Dr. Carpenter, who is with Inpatient Specialists, a group that contracts with hospitals to provide hospitalist services. The main risks are bleeding, low blood pressure, or respiratory distress. "The bleeding might not necessarily be obvious," as the antithrombotic agent is given locally and bleeding can be local as well.

Community hospitals that offer catheter-directed thrombolysis need sufficient commitment from vascular surgeons and robust postprocedure support, Dr. Carpenter said. The vascular surgery group should be able to offer the procedure to all patients who need it.

Around-the-clock hospitalist availability is a good idea, especially if the surgeon is not on the in-house staff. "Don’t do [this procedure] if the hospitalist is providing triage services at night," he advised.

With 23 full-time positions (translating into 40 full-time or part-time physicians), the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist, a 339-bed hospital, typically provides 10 hospitalists during weekdays (including one medical-psychiatric physician) and 8 on weekend days.

Besides the adult hospitalist group, the hospital has a pediatric hospitalist service, 24-hour in-house ICU hospitalist coverage, and a surgical hospitalist group. "Not many hospitals have surgical hospitalists," Dr. Carpenter noted. Laborists also are available 24 hours a day for in-house ob.gyn. consultations.

Dr. Carpenter, who has been a hospitalist since 2006, said that this "is how hospital-based medicine is progressing. "Shady Grove has been an early adopter" of expanded hospitalist services.

Dr. Carpenter and Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

With the advantage of around-the-clock hospitalist services, one community hospital has been able to offer catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy – a procedure typically available only at tertiary-care hospitals.

Dr. Brian A. Carpenter, medical director of the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Md., said that at least 12 patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolisms have undergone catheter-directed thrombolysis at the hospital. Many others have undergone the procedure for deep vein thrombosis in a lower extremity with vascular extension into the larger vessels of the pelvis.

Before the service was introduced, patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism were sent to a tertiary-care hospital if they were stable enough for transfer. Otherwise, they were monitored in the ICU, managed medically with systemic anticoagulation, and transferred later if they still needed further treatment.

Systemic anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary embolism, but the American Heart Association and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend a more aggressive approach for massive and submassive PE. Up to 60% of patients with massive PE die, data suggest, with two-thirds of the deaths occurring in the first hour after the embolus forms. Within 30 days after submassive PE, 15%-20% of patients die secondary to pulmonary hypertension and subsequent cor pulmonale, according to a data presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

The catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy at Shady Grove Adventist largely owes its success to a vascular surgeon who took the lead in establishing protocols and training support staff, with hospitalists as a key part of the team.

The vascular surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Y. Wang, reported on the outcomes of the first 12 patients, in whom the procedures were all technically successful. One patient developed hemodynamically significant bradycardia, but all patients were off supplemental oxygen within 24 hours of the procedure. There were no bleeding complications.

One patient died 14 hours after the procedure, most likely because of a paradoxical embolus to the intestine. The 11 surviving patients were discharged to home within 48 hours of the intervention, according to Dr. Wang of Horizon Vascular Specialists. The group contracts to provide vascular surgical care at Shady Grove Adventist and two other hospitals in Maryland.

Catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy can shorten stays in the ICU and the hospital, reduce or eliminate the need for home oxygen therapy, and help restore right heart function in patients with massive or submassive pulmonary embolism, Dr. Wang said. Patients with massive or submassive PE are offered catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy if they are hemodynamically unstable; if they have right heart dysfunction, elevated troponin, or pulmonary artery pressures greater than 70 mmHg; or if they are not weaning off intubation for oxygen within 5 days, Dr. Wang said. He excludes patients who are actively bleeding or who are not able to tolerate any systemic anticoagulation.

Recent surgery was not a disqualifying factor in his case series. "Typically, those patients were orthopedic in nature, with a hip or knee replacement," Dr. Wang said. The patient would develop a big pulmonary embolus, and the orthopedist would give a green light for aggressive treatment.

But most of the patients who have received catheter-directed thrombolytic procedures presented to the emergency department with lower extremity swelling, and were found on sonography to have a thrombus extending into the large pelvic vessels. Dr. Carpenter’s service admits approximately 90% of adult inpatients, so the hospitalists usually are the ones to determine which patients should be considered for the interventional approach and which ones get medical therapy.

Dr. Wang emphasized that the protocols are as important as technical expertise in catheter-directed thrombolysis. Protocols are in place for the ED, the ICU, and the hospitalist team for the early detection of DVT and pulmonary emboli, notification of the appropriate staff, and posttreatment care of patients. Dr. Wang also took the lead on the anticoagulation aspect of computerized physician order entry.

"In our institution, we use the same protocols for call-in and transport to the cath lab as for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, which allows us to get the patient up and into the fluoroscopy suite within 30 minutes," Dr. Wang said. The fluoroscopy suite must be available on an emergency basis.

"It’s amazing to see such a dramatic improvement in patient symptoms almost immediately post procedure," said Dr. Carpenter.

Patients who undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis require close postoperative monitoring, said Dr. Carpenter, who is with Inpatient Specialists, a group that contracts with hospitals to provide hospitalist services. The main risks are bleeding, low blood pressure, or respiratory distress. "The bleeding might not necessarily be obvious," as the antithrombotic agent is given locally and bleeding can be local as well.

Community hospitals that offer catheter-directed thrombolysis need sufficient commitment from vascular surgeons and robust postprocedure support, Dr. Carpenter said. The vascular surgery group should be able to offer the procedure to all patients who need it.

Around-the-clock hospitalist availability is a good idea, especially if the surgeon is not on the in-house staff. "Don’t do [this procedure] if the hospitalist is providing triage services at night," he advised.

With 23 full-time positions (translating into 40 full-time or part-time physicians), the adult hospitalist service at Shady Grove Adventist, a 339-bed hospital, typically provides 10 hospitalists during weekdays (including one medical-psychiatric physician) and 8 on weekend days.

Besides the adult hospitalist group, the hospital has a pediatric hospitalist service, 24-hour in-house ICU hospitalist coverage, and a surgical hospitalist group. "Not many hospitals have surgical hospitalists," Dr. Carpenter noted. Laborists also are available 24 hours a day for in-house ob.gyn. consultations.

Dr. Carpenter, who has been a hospitalist since 2006, said that this "is how hospital-based medicine is progressing. "Shady Grove has been an early adopter" of expanded hospitalist services.

Dr. Carpenter and Dr. Wang reported having no financial disclosures.

CAS, CEA Evaluated for Contralateral Occlusion

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of contralateral carotid artery occlusion is no reason to treat carotid artery stenosis with stenting instead of carotid endarterectomy, a review of 713 patients suggested.

Either endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting can be performed on patients with contralateral occlusion with good 30-day and midterm results, Dr. Luke P. Brewster and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"We do not support contralateral occlusion as an independent criterion for carotid artery stenting" over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion, said Dr. Brewster of Emory University, Atlanta.

Among 57 patients who underwent carotid artery therapy who also had contralateral occlusion, 7 of 39 patients died after carotid artery stenting (18%), compared with 1 of 18 patients after carotid endarterectomy (6%), during a mean midterm follow-up of 28 and 29 months, respectively.

In general, stroke risk is increased in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion contralateral to a carotid artery with significant stenosis. Contralateral occlusion has been suggested as an indication for stenting because of theoretical advantages from reduced ischemic procedural time, and because the procedure can be done without a vascular shunt and without general anesthesia. Carotid endarterectomy, on the other hand, has been associated with a lower procedural stroke rate.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed Emory University’s data on 713 consecutive patients who underwent either carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting from February 2007 to July 2011.

Among the 8% of patients who had contralateral occlusion, the treatment approach was based on the preference of each patient’s vascular surgeon, cardiologist, and/or interventional radiologist.

Patients in the carotid artery stenting group were more likely to have had prior neck surgery (18 of 39 patients; 46%), compared with patients in the carotid endarterectomy group (1 of 18 patients; 6%). The groups did not differ significantly in age (67 and 70 years, respectively), sex, proportion of symptomatic patients, degree of stenosis, history of carotid artery stenting on the contralateral side, smoking history, or rates of hypertension, transient ischemic attack, stroke, diabetes, myocardial infarction, or other factors.

In the carotid artery stenosis group, six procedures involved flow reversal. The main indications for stenting were prior neck surgery, contralateral occlusion, or radiation of the neck. In the carotid endarterectomy group, two procedures were performed with the patient awake, and 15 involved a shunt.

All the endarterectomies were completed; one stenting procedure was aborted and the patient underwent an endarterectomy during the same hospitalization.

At 30 days after surgery, two patients (5%) in the stenting group had died following an access-site bleed or respiratory failure in a patient with a seizure disorder. No patients in the endarterectomy group died. Two patients in the stenting group developed transient ischemic attacks. There was no MI or stroke in either group, Dr. Brewster said.

Patients in the endarterectomy group stayed in the hospital significantly longer (average, 3 days vs. 2 days in the stenting group). Five patients (28%) in the endarterectomy group were admitted to the ICU, all for observation due to medical morbidities. Seven patients (18%) in the stenting group were admitted to the ICU, three of them due to bradycardia or hypotension.

Midterm results included a mean of 29 months of follow-up in the endarterectomy group and 28 months in the stenting group. Two patients required reinterventions after carotid artery stenting, compared with none after endarterectomy.

Five more patients in the stenting group died at a mean of 23 months after the procedure (excluding the two perioperative deaths), compared with one death at a mean of 42 months after endarterectomy. All six of these late deaths were in patients with hypertension, five of whom also had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Three of the six patients had diabetes, and two had a history of prior stroke.

The findings "fail to demonstrate superiority of carotid artery stenting over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion," Dr. Brewster said.

Dr. Brewster reported having no financial disclosures.

There were six late deaths after carotid artery stenting. When you look at those cases, it begs the question as to whether any carotid intervention at all should be done. In my practice, I see patients all the time to whom I just have to say "No," because I know these patients will drag down results and they really have very little life expectancy.

I wonder, what was the timing of the transient ischemic attacks? Were they intraprocedural or late? What we’ve run into recently are cases of platelet resistance. We’re doing platelet inhibition studies before we ever go into the lab to make sure that our dual-antiplatelet therapy is really working.

What are the indications for carotid artery stenting at Emory University right now?

I’m concerned that the numbers are too low to draw any meaningful conclusions. This study shows, like many individual series and meta-analyses, that you can get great surgical results. The problem is, over the last 12 months there have been two very important publications that have looked at large series of carotid endarterectomies and the development of contralateral occlusion. The risk of stroke from carotid endarterectomy with contralateral occlusion was approximately twice as high as without contralateral occlusion in large series of patients – I’m talking about hundreds of patients.

This is still something that we have to take seriously. The carotid artery stenting lobby is not going to give us a free pass on this.

Dr. Charles B. Ross is a vascular specialist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). These comments have been adapted from his remarks as an official discussant of Dr. Brewster’s presentation at the meeting. He has been a board member for Abbott Vascular.

There were six late deaths after carotid artery stenting. When you look at those cases, it begs the question as to whether any carotid intervention at all should be done. In my practice, I see patients all the time to whom I just have to say "No," because I know these patients will drag down results and they really have very little life expectancy.

I wonder, what was the timing of the transient ischemic attacks? Were they intraprocedural or late? What we’ve run into recently are cases of platelet resistance. We’re doing platelet inhibition studies before we ever go into the lab to make sure that our dual-antiplatelet therapy is really working.

What are the indications for carotid artery stenting at Emory University right now?

I’m concerned that the numbers are too low to draw any meaningful conclusions. This study shows, like many individual series and meta-analyses, that you can get great surgical results. The problem is, over the last 12 months there have been two very important publications that have looked at large series of carotid endarterectomies and the development of contralateral occlusion. The risk of stroke from carotid endarterectomy with contralateral occlusion was approximately twice as high as without contralateral occlusion in large series of patients – I’m talking about hundreds of patients.

This is still something that we have to take seriously. The carotid artery stenting lobby is not going to give us a free pass on this.

Dr. Charles B. Ross is a vascular specialist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). These comments have been adapted from his remarks as an official discussant of Dr. Brewster’s presentation at the meeting. He has been a board member for Abbott Vascular.

There were six late deaths after carotid artery stenting. When you look at those cases, it begs the question as to whether any carotid intervention at all should be done. In my practice, I see patients all the time to whom I just have to say "No," because I know these patients will drag down results and they really have very little life expectancy.

I wonder, what was the timing of the transient ischemic attacks? Were they intraprocedural or late? What we’ve run into recently are cases of platelet resistance. We’re doing platelet inhibition studies before we ever go into the lab to make sure that our dual-antiplatelet therapy is really working.

What are the indications for carotid artery stenting at Emory University right now?

I’m concerned that the numbers are too low to draw any meaningful conclusions. This study shows, like many individual series and meta-analyses, that you can get great surgical results. The problem is, over the last 12 months there have been two very important publications that have looked at large series of carotid endarterectomies and the development of contralateral occlusion. The risk of stroke from carotid endarterectomy with contralateral occlusion was approximately twice as high as without contralateral occlusion in large series of patients – I’m talking about hundreds of patients.

This is still something that we have to take seriously. The carotid artery stenting lobby is not going to give us a free pass on this.

Dr. Charles B. Ross is a vascular specialist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). These comments have been adapted from his remarks as an official discussant of Dr. Brewster’s presentation at the meeting. He has been a board member for Abbott Vascular.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of contralateral carotid artery occlusion is no reason to treat carotid artery stenosis with stenting instead of carotid endarterectomy, a review of 713 patients suggested.

Either endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting can be performed on patients with contralateral occlusion with good 30-day and midterm results, Dr. Luke P. Brewster and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"We do not support contralateral occlusion as an independent criterion for carotid artery stenting" over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion, said Dr. Brewster of Emory University, Atlanta.

Among 57 patients who underwent carotid artery therapy who also had contralateral occlusion, 7 of 39 patients died after carotid artery stenting (18%), compared with 1 of 18 patients after carotid endarterectomy (6%), during a mean midterm follow-up of 28 and 29 months, respectively.

In general, stroke risk is increased in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion contralateral to a carotid artery with significant stenosis. Contralateral occlusion has been suggested as an indication for stenting because of theoretical advantages from reduced ischemic procedural time, and because the procedure can be done without a vascular shunt and without general anesthesia. Carotid endarterectomy, on the other hand, has been associated with a lower procedural stroke rate.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed Emory University’s data on 713 consecutive patients who underwent either carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting from February 2007 to July 2011.

Among the 8% of patients who had contralateral occlusion, the treatment approach was based on the preference of each patient’s vascular surgeon, cardiologist, and/or interventional radiologist.

Patients in the carotid artery stenting group were more likely to have had prior neck surgery (18 of 39 patients; 46%), compared with patients in the carotid endarterectomy group (1 of 18 patients; 6%). The groups did not differ significantly in age (67 and 70 years, respectively), sex, proportion of symptomatic patients, degree of stenosis, history of carotid artery stenting on the contralateral side, smoking history, or rates of hypertension, transient ischemic attack, stroke, diabetes, myocardial infarction, or other factors.

In the carotid artery stenosis group, six procedures involved flow reversal. The main indications for stenting were prior neck surgery, contralateral occlusion, or radiation of the neck. In the carotid endarterectomy group, two procedures were performed with the patient awake, and 15 involved a shunt.

All the endarterectomies were completed; one stenting procedure was aborted and the patient underwent an endarterectomy during the same hospitalization.

At 30 days after surgery, two patients (5%) in the stenting group had died following an access-site bleed or respiratory failure in a patient with a seizure disorder. No patients in the endarterectomy group died. Two patients in the stenting group developed transient ischemic attacks. There was no MI or stroke in either group, Dr. Brewster said.

Patients in the endarterectomy group stayed in the hospital significantly longer (average, 3 days vs. 2 days in the stenting group). Five patients (28%) in the endarterectomy group were admitted to the ICU, all for observation due to medical morbidities. Seven patients (18%) in the stenting group were admitted to the ICU, three of them due to bradycardia or hypotension.

Midterm results included a mean of 29 months of follow-up in the endarterectomy group and 28 months in the stenting group. Two patients required reinterventions after carotid artery stenting, compared with none after endarterectomy.

Five more patients in the stenting group died at a mean of 23 months after the procedure (excluding the two perioperative deaths), compared with one death at a mean of 42 months after endarterectomy. All six of these late deaths were in patients with hypertension, five of whom also had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Three of the six patients had diabetes, and two had a history of prior stroke.

The findings "fail to demonstrate superiority of carotid artery stenting over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion," Dr. Brewster said.

Dr. Brewster reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – The presence of contralateral carotid artery occlusion is no reason to treat carotid artery stenosis with stenting instead of carotid endarterectomy, a review of 713 patients suggested.

Either endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting can be performed on patients with contralateral occlusion with good 30-day and midterm results, Dr. Luke P. Brewster and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"We do not support contralateral occlusion as an independent criterion for carotid artery stenting" over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion, said Dr. Brewster of Emory University, Atlanta.

Among 57 patients who underwent carotid artery therapy who also had contralateral occlusion, 7 of 39 patients died after carotid artery stenting (18%), compared with 1 of 18 patients after carotid endarterectomy (6%), during a mean midterm follow-up of 28 and 29 months, respectively.

In general, stroke risk is increased in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion contralateral to a carotid artery with significant stenosis. Contralateral occlusion has been suggested as an indication for stenting because of theoretical advantages from reduced ischemic procedural time, and because the procedure can be done without a vascular shunt and without general anesthesia. Carotid endarterectomy, on the other hand, has been associated with a lower procedural stroke rate.

The investigators retrospectively reviewed Emory University’s data on 713 consecutive patients who underwent either carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting from February 2007 to July 2011.

Among the 8% of patients who had contralateral occlusion, the treatment approach was based on the preference of each patient’s vascular surgeon, cardiologist, and/or interventional radiologist.

Patients in the carotid artery stenting group were more likely to have had prior neck surgery (18 of 39 patients; 46%), compared with patients in the carotid endarterectomy group (1 of 18 patients; 6%). The groups did not differ significantly in age (67 and 70 years, respectively), sex, proportion of symptomatic patients, degree of stenosis, history of carotid artery stenting on the contralateral side, smoking history, or rates of hypertension, transient ischemic attack, stroke, diabetes, myocardial infarction, or other factors.

In the carotid artery stenosis group, six procedures involved flow reversal. The main indications for stenting were prior neck surgery, contralateral occlusion, or radiation of the neck. In the carotid endarterectomy group, two procedures were performed with the patient awake, and 15 involved a shunt.

All the endarterectomies were completed; one stenting procedure was aborted and the patient underwent an endarterectomy during the same hospitalization.

At 30 days after surgery, two patients (5%) in the stenting group had died following an access-site bleed or respiratory failure in a patient with a seizure disorder. No patients in the endarterectomy group died. Two patients in the stenting group developed transient ischemic attacks. There was no MI or stroke in either group, Dr. Brewster said.

Patients in the endarterectomy group stayed in the hospital significantly longer (average, 3 days vs. 2 days in the stenting group). Five patients (28%) in the endarterectomy group were admitted to the ICU, all for observation due to medical morbidities. Seven patients (18%) in the stenting group were admitted to the ICU, three of them due to bradycardia or hypotension.

Midterm results included a mean of 29 months of follow-up in the endarterectomy group and 28 months in the stenting group. Two patients required reinterventions after carotid artery stenting, compared with none after endarterectomy.

Five more patients in the stenting group died at a mean of 23 months after the procedure (excluding the two perioperative deaths), compared with one death at a mean of 42 months after endarterectomy. All six of these late deaths were in patients with hypertension, five of whom also had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Three of the six patients had diabetes, and two had a history of prior stroke.

The findings "fail to demonstrate superiority of carotid artery stenting over carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion," Dr. Brewster said.

Dr. Brewster reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN ASSOCIATION FOR VASCULAR SURGERY

Major Finding: Seven patients (18%) with contralateral occlusion died after carotid artery stenting and two required reinterventions, compared with one death (6%) and no reinterventions after carotid endarterectomy.

Data Source: Data are from a retrospective study of 39 patients treated with carotid artery stenting and 18 treated with carotid endarterectomy for carotid artery stenosis, with mean follow-ups of 29 and 28 months, respectively. All had contralateral occlusion.

Disclosures: Dr. Brewster reported having no financial disclosures.

Initial EVAR Improves Mortality After Second Aortic Repair

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Repairing a first abdominal aortic aneurysm by endovascular techniques instead of open surgery improves survival if the patient eventually needs a second aortic repair of either kind, a retrospective study of 149 patients suggests.

Among 2,256 abdominal aneurysm repairs performed at one institution in 1986-2011, 149 patients (7%) required secondary aortic procedures – EVAR (endovascular aneurysm repair) or TEVAR (transthoracic endovascular aneurysm repair) in 77 patients, and an open surgical repair after initial EVAR/TEVAR in 72 patients.

For the 77 patients who first underwent EVAR or TEVAR (referred to jointly as EVAR in the study), 10 of 61 patients died within 1 year of a second EVAR (16%) and 2 of 16 patients died within 1 year of an open repair after the initial EVAR (13%).

Among the 72 patients who first underwent open surgical aneurysm repair, 10 of 36 patients died within 1 year of EVAR after an initial open repair (28%), and 8 of 36 patients died within 1 year of a second open repair (22%), Dr. Dean J. Yamaguchi and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"The initial operative approach to abdominal aortic aneurysm influences mortality in patients who require secondary repair," said Dr. Yamaguchi of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "Survival is greatest for patients who undergo initial EVAR, even if a secondary open repair is required."

Previous studies have suggested that 12%-20% of patients undergoing EVAR eventually require secondary interventions because of stent graft migration, fracture, or aneurysmal disease progression (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2398-405; Lancet 2005;365:2179-86). Although a second EVAR may be possible in most of these patients, it hasn’t been clear how this might affect mortality, he said.

A review of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s experience with EVAR and open aortic aneurysm repair found that patients undergoing EVAR had better long-term survival than did patients treated by open repair, but the EVAR group required more secondary procedures related to the aortic graft. Patients in the open-repair group required more nonvascular interventions subsequently (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1592-8).

The current study of patients undergoing secondary aortic repairs excluded secondary interventions involving the ascending aorta or iliac arteries.

Patients who had an initial open repair were significantly younger than patients who initially underwent EVAR, and the time between the primary and secondary interventions was significantly longer after initial open repairs than after initial EVAR.

The mean age at the time of the first intervention was 69 years for patients who underwent two EVARs, 68 years in the initial EVAR and secondary open-repair group, 60 years in the initial open-repair and secondary EVAR group, and 63 years for patients who underwent two open repairs. The interval between the first and second intervention was 3 years in the EVAR/open group, 2 years in the EVAR/EVAR group, 13 years in the open/EVAR group, and 7 years in the open/open group.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for the effects of confounding factors, the risk of dying within 1 year of a secondary intervention was three times higher in the open/EVAR group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, a statistically significant difference. The 1-year death rates after secondary intervention were higher in the open/open group and lower in the EVAR/open group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, but these differences were not statistically significant, Dr. Yamaguchi reported.

The study controlled for the effects of age at the time of the secondary aortic procedure; sex; race; duration between first and second aortic procedures; coronary artery disease; hypertension; hyperlipidemia; stroke; obesity; and diabetes.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature and by drawing data from a single institution. Also, the study did not include anatomical data, and EVAR may be chosen for intervention based on anatomy, not necessarily by medical condition, he said.

The patient groups did not differ significantly in age at the time of secondary intervention; sex; the percentage of nonwhite patients or smokers; or in the proportions of patients with a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia.

Dr. Yamaguchi reported having no financial disclosures.

Conventional wisdom in the life insurance industry says that younger individuals generally live longer than older people. Age being equal, we might hypothesize that the sequence and method of aneurysm intervention could influence subsequent survival to a greater degree.

Dr. Yamaguchi and his colleagues found that patients receiving initial open repairs had higher subsequent mortality after secondary procedures than did patients initially treated by endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Explanations for this observation are not completely clear. In the Kaplan-Meyer survival curve encompassing the four patient groups mentioned (EVAR/EVAR, EVAR/open, open/EVAR, and open/open), it appears that most of the separation in survival trends occurred in the first 12 months after the secondary intervention.

Is this difference in survival after secondary interventions explained by periprocedural mortality measured at 30-, 60-, or 90-day intervals after intervention? Details of the specific secondary procedures performed and their relative physiological magnitude may explain some or most of these survival trends.

An alternative explanation that could account for the study results was not considered by the authors. Open aneurysm repair patients were, on average, 6-7 years younger than the EVAR patients at their initial procedure, even though secondary interventions were done at an equivalent age in each group (roughly 72 years). An earlier age of onset of disease is known to predict higher mortality in coronary atherosclerosis. This may be true, as well, for aneurysmal disease.

Dr. Martin R. Back is chief of vascular surgery at James A. Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, Fla. These comments are adapted from remarks he made as the official discussant at the meeting. Dr. Back reported having no financial disclosures.

Conventional wisdom in the life insurance industry says that younger individuals generally live longer than older people. Age being equal, we might hypothesize that the sequence and method of aneurysm intervention could influence subsequent survival to a greater degree.

Dr. Yamaguchi and his colleagues found that patients receiving initial open repairs had higher subsequent mortality after secondary procedures than did patients initially treated by endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Explanations for this observation are not completely clear. In the Kaplan-Meyer survival curve encompassing the four patient groups mentioned (EVAR/EVAR, EVAR/open, open/EVAR, and open/open), it appears that most of the separation in survival trends occurred in the first 12 months after the secondary intervention.

Is this difference in survival after secondary interventions explained by periprocedural mortality measured at 30-, 60-, or 90-day intervals after intervention? Details of the specific secondary procedures performed and their relative physiological magnitude may explain some or most of these survival trends.

An alternative explanation that could account for the study results was not considered by the authors. Open aneurysm repair patients were, on average, 6-7 years younger than the EVAR patients at their initial procedure, even though secondary interventions were done at an equivalent age in each group (roughly 72 years). An earlier age of onset of disease is known to predict higher mortality in coronary atherosclerosis. This may be true, as well, for aneurysmal disease.

Dr. Martin R. Back is chief of vascular surgery at James A. Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, Fla. These comments are adapted from remarks he made as the official discussant at the meeting. Dr. Back reported having no financial disclosures.

Conventional wisdom in the life insurance industry says that younger individuals generally live longer than older people. Age being equal, we might hypothesize that the sequence and method of aneurysm intervention could influence subsequent survival to a greater degree.

Dr. Yamaguchi and his colleagues found that patients receiving initial open repairs had higher subsequent mortality after secondary procedures than did patients initially treated by endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Explanations for this observation are not completely clear. In the Kaplan-Meyer survival curve encompassing the four patient groups mentioned (EVAR/EVAR, EVAR/open, open/EVAR, and open/open), it appears that most of the separation in survival trends occurred in the first 12 months after the secondary intervention.

Is this difference in survival after secondary interventions explained by periprocedural mortality measured at 30-, 60-, or 90-day intervals after intervention? Details of the specific secondary procedures performed and their relative physiological magnitude may explain some or most of these survival trends.

An alternative explanation that could account for the study results was not considered by the authors. Open aneurysm repair patients were, on average, 6-7 years younger than the EVAR patients at their initial procedure, even though secondary interventions were done at an equivalent age in each group (roughly 72 years). An earlier age of onset of disease is known to predict higher mortality in coronary atherosclerosis. This may be true, as well, for aneurysmal disease.

Dr. Martin R. Back is chief of vascular surgery at James A. Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, Fla. These comments are adapted from remarks he made as the official discussant at the meeting. Dr. Back reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Repairing a first abdominal aortic aneurysm by endovascular techniques instead of open surgery improves survival if the patient eventually needs a second aortic repair of either kind, a retrospective study of 149 patients suggests.

Among 2,256 abdominal aneurysm repairs performed at one institution in 1986-2011, 149 patients (7%) required secondary aortic procedures – EVAR (endovascular aneurysm repair) or TEVAR (transthoracic endovascular aneurysm repair) in 77 patients, and an open surgical repair after initial EVAR/TEVAR in 72 patients.

For the 77 patients who first underwent EVAR or TEVAR (referred to jointly as EVAR in the study), 10 of 61 patients died within 1 year of a second EVAR (16%) and 2 of 16 patients died within 1 year of an open repair after the initial EVAR (13%).

Among the 72 patients who first underwent open surgical aneurysm repair, 10 of 36 patients died within 1 year of EVAR after an initial open repair (28%), and 8 of 36 patients died within 1 year of a second open repair (22%), Dr. Dean J. Yamaguchi and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"The initial operative approach to abdominal aortic aneurysm influences mortality in patients who require secondary repair," said Dr. Yamaguchi of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "Survival is greatest for patients who undergo initial EVAR, even if a secondary open repair is required."

Previous studies have suggested that 12%-20% of patients undergoing EVAR eventually require secondary interventions because of stent graft migration, fracture, or aneurysmal disease progression (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2398-405; Lancet 2005;365:2179-86). Although a second EVAR may be possible in most of these patients, it hasn’t been clear how this might affect mortality, he said.

A review of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s experience with EVAR and open aortic aneurysm repair found that patients undergoing EVAR had better long-term survival than did patients treated by open repair, but the EVAR group required more secondary procedures related to the aortic graft. Patients in the open-repair group required more nonvascular interventions subsequently (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1592-8).

The current study of patients undergoing secondary aortic repairs excluded secondary interventions involving the ascending aorta or iliac arteries.

Patients who had an initial open repair were significantly younger than patients who initially underwent EVAR, and the time between the primary and secondary interventions was significantly longer after initial open repairs than after initial EVAR.

The mean age at the time of the first intervention was 69 years for patients who underwent two EVARs, 68 years in the initial EVAR and secondary open-repair group, 60 years in the initial open-repair and secondary EVAR group, and 63 years for patients who underwent two open repairs. The interval between the first and second intervention was 3 years in the EVAR/open group, 2 years in the EVAR/EVAR group, 13 years in the open/EVAR group, and 7 years in the open/open group.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for the effects of confounding factors, the risk of dying within 1 year of a secondary intervention was three times higher in the open/EVAR group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, a statistically significant difference. The 1-year death rates after secondary intervention were higher in the open/open group and lower in the EVAR/open group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, but these differences were not statistically significant, Dr. Yamaguchi reported.

The study controlled for the effects of age at the time of the secondary aortic procedure; sex; race; duration between first and second aortic procedures; coronary artery disease; hypertension; hyperlipidemia; stroke; obesity; and diabetes.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature and by drawing data from a single institution. Also, the study did not include anatomical data, and EVAR may be chosen for intervention based on anatomy, not necessarily by medical condition, he said.

The patient groups did not differ significantly in age at the time of secondary intervention; sex; the percentage of nonwhite patients or smokers; or in the proportions of patients with a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia.

Dr. Yamaguchi reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Repairing a first abdominal aortic aneurysm by endovascular techniques instead of open surgery improves survival if the patient eventually needs a second aortic repair of either kind, a retrospective study of 149 patients suggests.

Among 2,256 abdominal aneurysm repairs performed at one institution in 1986-2011, 149 patients (7%) required secondary aortic procedures – EVAR (endovascular aneurysm repair) or TEVAR (transthoracic endovascular aneurysm repair) in 77 patients, and an open surgical repair after initial EVAR/TEVAR in 72 patients.

For the 77 patients who first underwent EVAR or TEVAR (referred to jointly as EVAR in the study), 10 of 61 patients died within 1 year of a second EVAR (16%) and 2 of 16 patients died within 1 year of an open repair after the initial EVAR (13%).

Among the 72 patients who first underwent open surgical aneurysm repair, 10 of 36 patients died within 1 year of EVAR after an initial open repair (28%), and 8 of 36 patients died within 1 year of a second open repair (22%), Dr. Dean J. Yamaguchi and his associates reported at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"The initial operative approach to abdominal aortic aneurysm influences mortality in patients who require secondary repair," said Dr. Yamaguchi of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "Survival is greatest for patients who undergo initial EVAR, even if a secondary open repair is required."

Previous studies have suggested that 12%-20% of patients undergoing EVAR eventually require secondary interventions because of stent graft migration, fracture, or aneurysmal disease progression (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2398-405; Lancet 2005;365:2179-86). Although a second EVAR may be possible in most of these patients, it hasn’t been clear how this might affect mortality, he said.

A review of the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s experience with EVAR and open aortic aneurysm repair found that patients undergoing EVAR had better long-term survival than did patients treated by open repair, but the EVAR group required more secondary procedures related to the aortic graft. Patients in the open-repair group required more nonvascular interventions subsequently (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1592-8).

The current study of patients undergoing secondary aortic repairs excluded secondary interventions involving the ascending aorta or iliac arteries.

Patients who had an initial open repair were significantly younger than patients who initially underwent EVAR, and the time between the primary and secondary interventions was significantly longer after initial open repairs than after initial EVAR.

The mean age at the time of the first intervention was 69 years for patients who underwent two EVARs, 68 years in the initial EVAR and secondary open-repair group, 60 years in the initial open-repair and secondary EVAR group, and 63 years for patients who underwent two open repairs. The interval between the first and second intervention was 3 years in the EVAR/open group, 2 years in the EVAR/EVAR group, 13 years in the open/EVAR group, and 7 years in the open/open group.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for the effects of confounding factors, the risk of dying within 1 year of a secondary intervention was three times higher in the open/EVAR group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, a statistically significant difference. The 1-year death rates after secondary intervention were higher in the open/open group and lower in the EVAR/open group, compared with the EVAR/EVAR group, but these differences were not statistically significant, Dr. Yamaguchi reported.

The study controlled for the effects of age at the time of the secondary aortic procedure; sex; race; duration between first and second aortic procedures; coronary artery disease; hypertension; hyperlipidemia; stroke; obesity; and diabetes.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature and by drawing data from a single institution. Also, the study did not include anatomical data, and EVAR may be chosen for intervention based on anatomy, not necessarily by medical condition, he said.

The patient groups did not differ significantly in age at the time of secondary intervention; sex; the percentage of nonwhite patients or smokers; or in the proportions of patients with a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia.

Dr. Yamaguchi reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN ASSOCIATION FOR VASCULAR SURGERY

Major Finding: Patients undergoing a secondary abdominal aortic aneurysm repair by EVAR were three times more likely to die within a year if the primary repair was open surgery rather than an initial EVAR.

Data Source: The researchers did a retrospective review of 149 patients requiring secondary aortic procedures at one institution in a 25-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Yamaguchi reported having no financial disclosures.

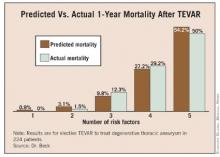

Risk Factors Predict 1-Year Mortality After Elective TEVAR

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN ASSOCIATION FOR VASCULAR SURGERY

Endovascular Repair Effective for Inflammatory AAA

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms can be treated safely and effectively by endovascular aneurysm repair, though patients with significant hydronephrosis may have worse outcomes, a retrospective study suggests.

The study included 69 patients who underwent either endovascular repair (10 patients) or open surgical repair (59 patients) at the surgeon’s discretion at Mayo Clinics in Minnesota, Florida, or Arizona between 1999 and 2011.

Previous case series and meta-analyses have reported mixed results with endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), but the current study suggests that EVAR is appropriate management for inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), Dr. William M. Stone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In the study’s EVAR group, eight patients presented with symptoms (80%), including one with rupture. In the open-repair group, 31 patients (52%) presented with symptoms, including 3 with rupture (5%).

Ureteral involvement was seen in 23 patients: 2 patients in the EVAR group (20%) and 21 in the open group (34%). Of these 23 patients, 21 underwent preoperative ureteral stent placement (91%). Thirty-six patients in the open-repair group had suprarenal aortic cross clamps (61%).

All of the EVAR procedures were technically successful, and patients were followed for an average of 34 months. The mean aneurysm size in the EVAR group decreased from 5.94 cm preoperatively to 4.73 cm after EVAR, an average change of nearly 18%, reported Dr. Stone of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix.

Aneurysm size decreased in seven patients (70%), and did not change in two patients (20%) after EVAR. One EVAR patient was lost to follow-up. Preoperative hydronephrosis in one patient (10%) before EVAR did not change after EVAR, and one patient developed new hydronephrosis after EVAR. No patients in the EVAR group died, developed endoleaks, or needed steroids. Two patients developed atrial fibrillation after EVAR and were treated for it.

The inflammatory rind measured 5.4 cm before EVAR and 2.7 cm afterward on average, a mean change of 50%, he said.

In the open-repair group, surgeons used midline incisions in 52 patients (88%), a left flank approach in 6 patients (10%), and a bilateral subcostal approach in 1 (2%) to repair aneurysms with a mean size of 6.3 cm.