User login

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have well-established efficacy for treating depression, panic disorder, and social phobia. However, a lack of familiarity with these agents and misconceptions about the risks associated with their use have led to MAOIs being substantially underutilized. The goal of this 2-part guide to MAOIs is to educate clinicians about this often-overlooked class of medications. Part 1 (“A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

MAOIs and potential drug interactions

One source of concern in patients receiving irreversible nonselective MAOIs is the development of excessive serotonergic neurotransmission resulting in SS. In the 1960s, researchers noted that administering large doses of

- mild symptoms: tremor, akathisia, inducible clonus

- moderate symptoms: spontaneous or sustained clonus, muscular hypertonicity

- severe symptoms: hyperthermia, diaphoresis.2

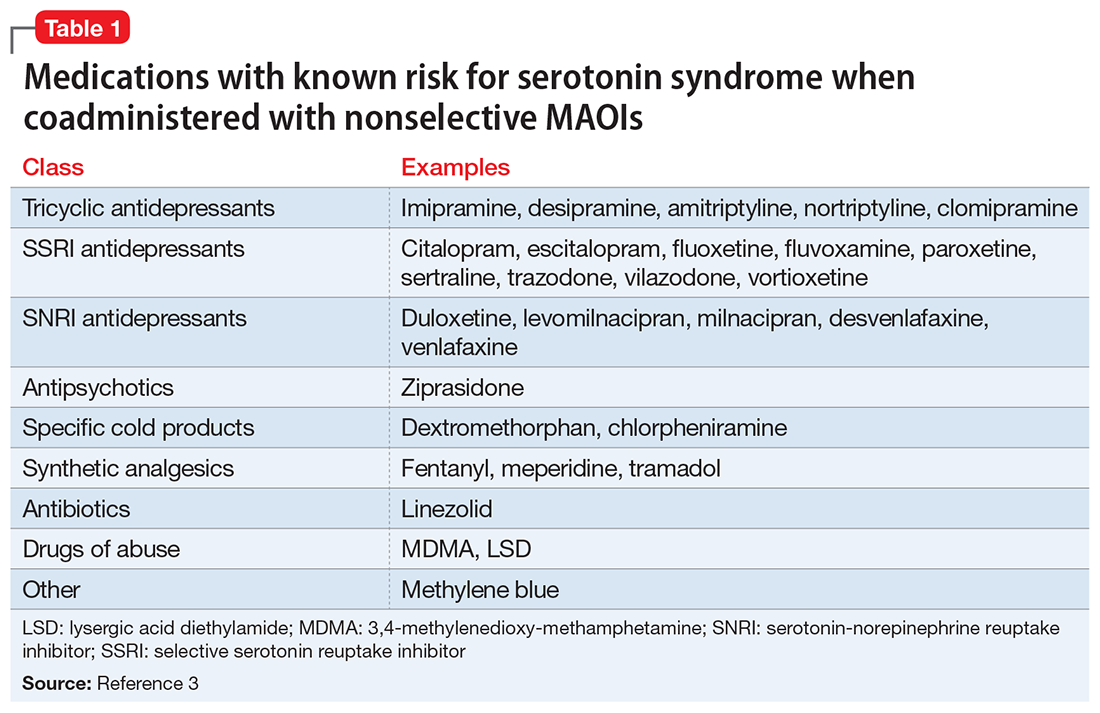

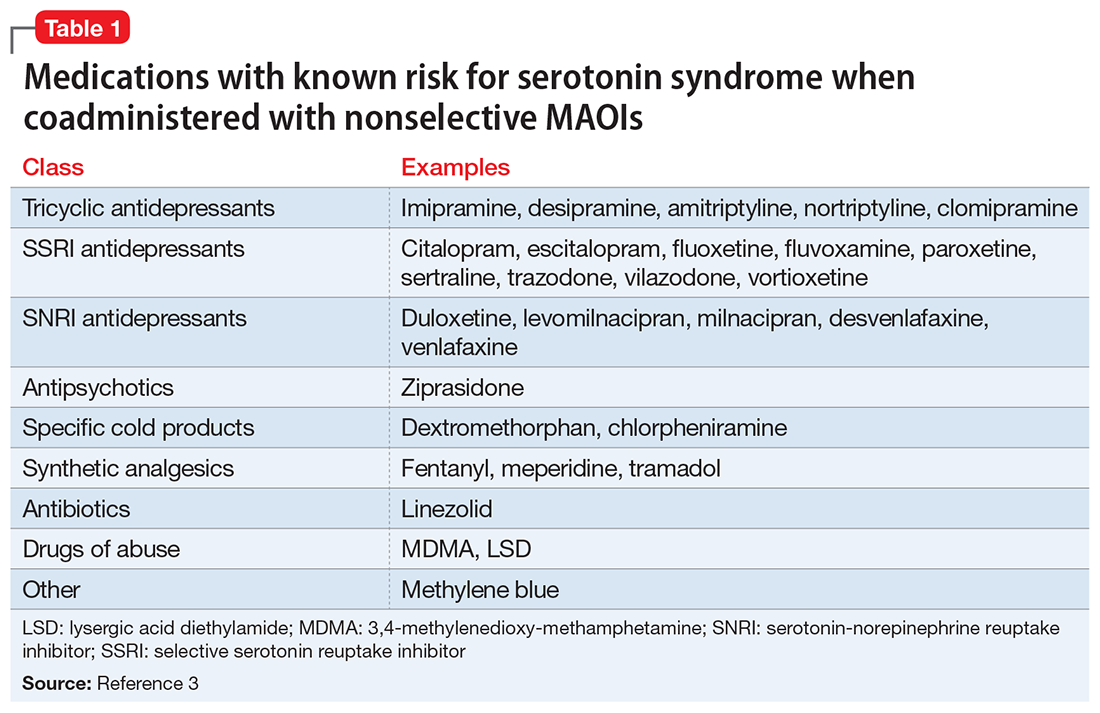

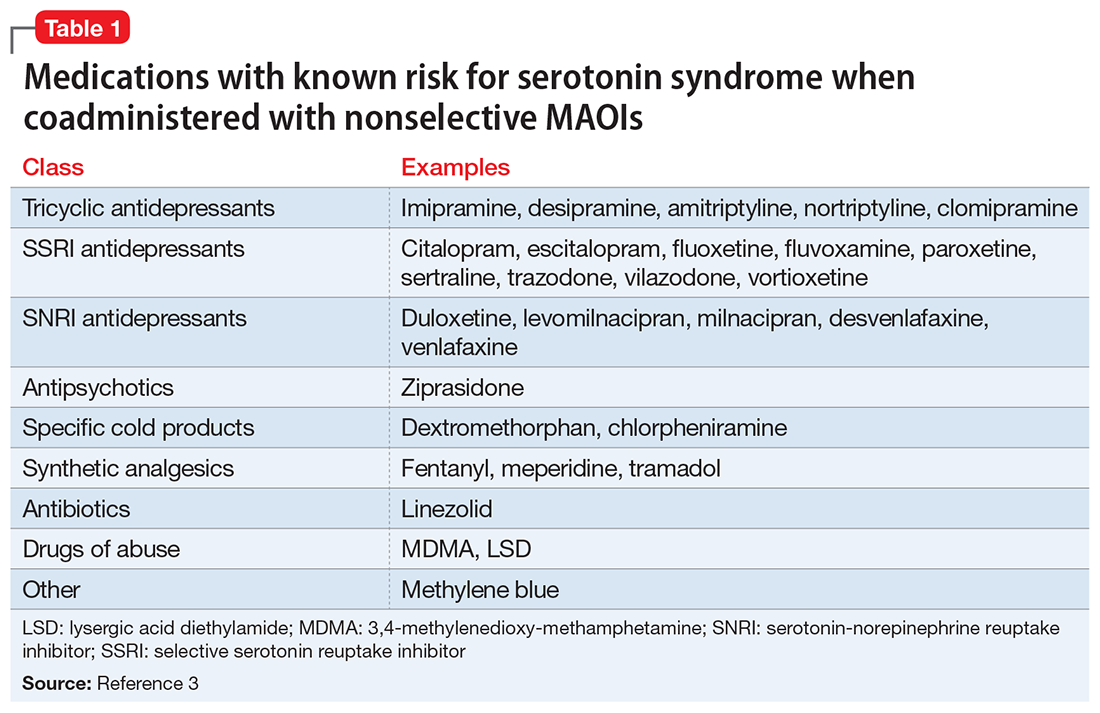

Although SS can be induced by significant exposure to individual agents that promote excess synaptic serotonin (eg, overdose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), the majority of fatal cases have occurred among patients taking MAOIs who were coadministered an agent that inhibited serotonin reuptake (Table 13). Animal studies have determined that excessive stimulation of the 5HT2A receptor is primarily responsible for SS,4 and that 5HT2A antagonists, such as mirtazapine, can block the development of SS in a mouse coadministered

Risk for SS. Most medications that promote serotonergic activity are well known for their use as antidepressants, but other agents that have 5HT reuptake properties (eg, the antihistamine chlorpheniramine) must be avoided. Although older literature suggests that the use of lower doses of certain tricyclic antidepressants concurrently with MAOIs may not be as dangerous as once believed,6 there are sufficient reports of serious outcomes that tricyclics should be avoided in patients taking MAOIs because of the risk of SS, and also because, in general, tricyclics are poorly tolerated.7

Desipramine, a potent norepinephrine transporter (NET) inhibitor, blocks the entry of tyramine into cells by NET, thereby preventing hypertensive events in animal models of tyramine overexposure. However, in some assays, the affinity for the serotonin transporter is not insignificant, so at higher doses desipramine may pose the same theoretical risk for SS as seen with other tricyclics.3

Lastly

Astute clinicians will recognize that antidepressants that lack 5HT reuptake (eg, bupropion, mirtazapine) are not on this list of agents that may increase SS risk when taken with an MAOI. Older papers often list mirtazapine, but as a 5HT2A antagonist, it does not possess a plausible mechanism by which it can induce 5HT toxicity.9,10 Most atypical antipsychotics have significant 5HT2A antagonism and can be combined with MAOIs, but ziprasidone is an exception: as a moderate SNRI, it has been associated with SS when administered with an MAOI.11

Pressor reactions. The only theoretical sources of concern for pressor effects are medications that act as norepinephrine releasers through interactions at the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) (for more information on TAAR1, see

Starting a patient on an MAOI

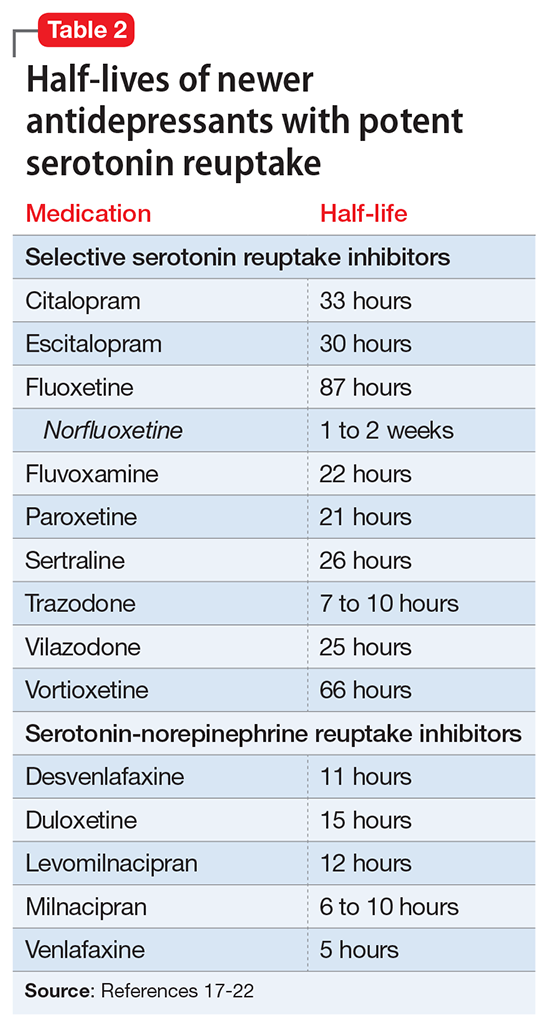

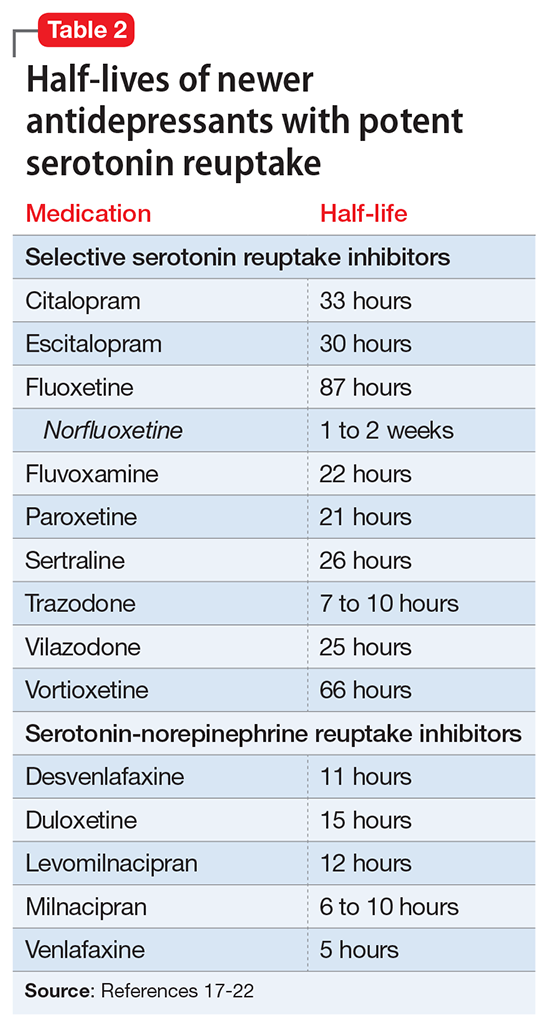

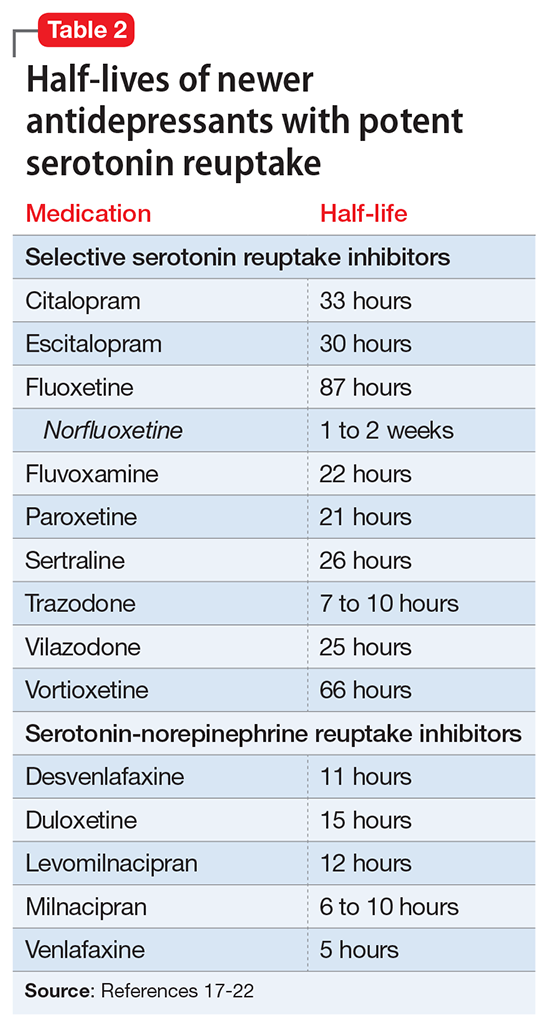

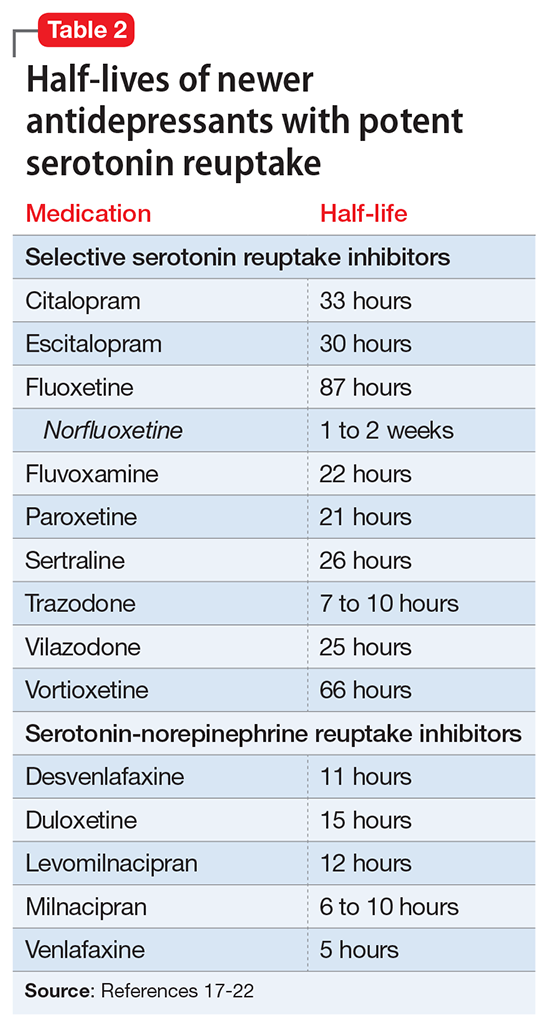

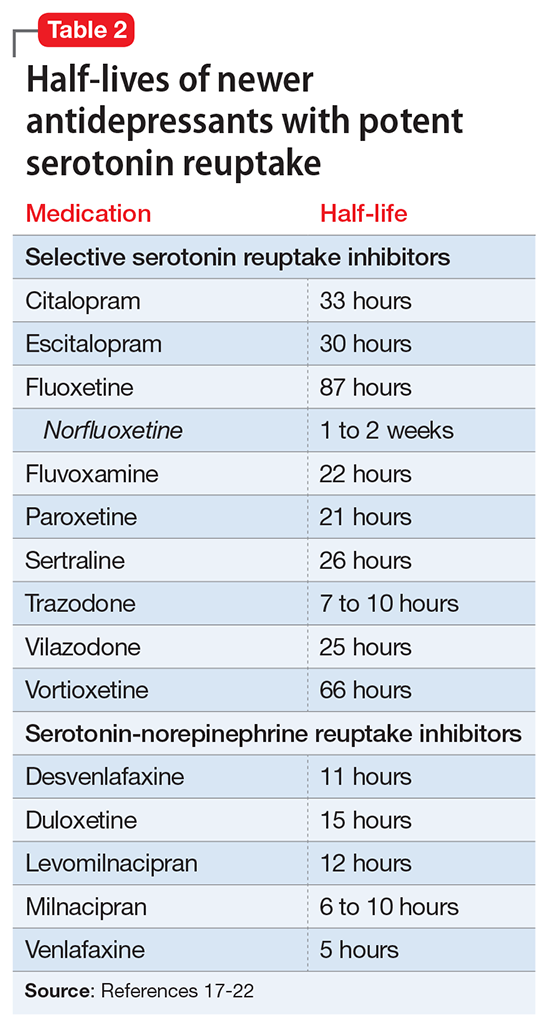

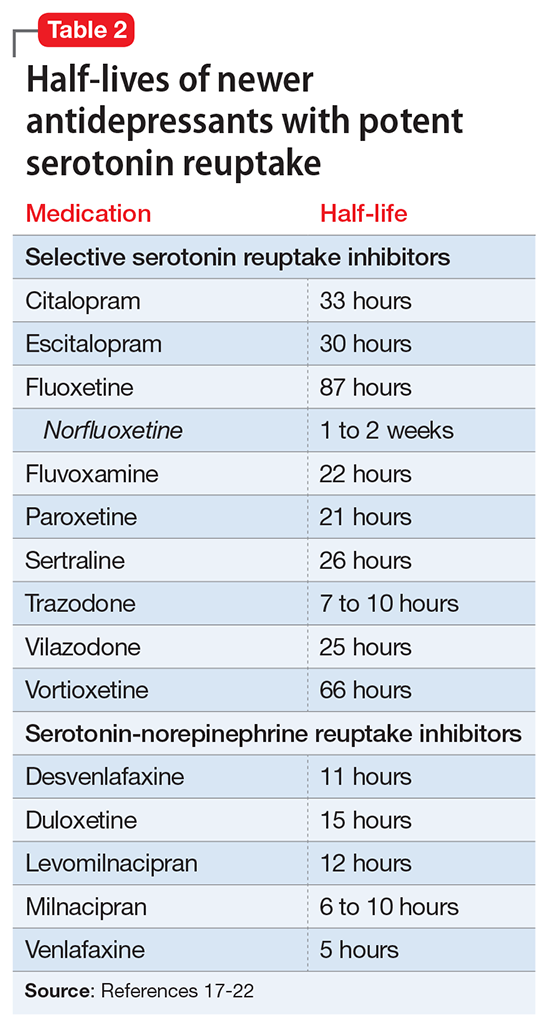

Contraindicated medications need to be tapered before beginning MAOI treatment. The duration of the washout period depends on the half-life of the medication and any active metabolites. Antidepressants with half-lives of approximately ≤24 hours should be tapered over 7 to 14 days (depending on the dose) to minimize the risk of withdrawal syndromes, while those with long half-lives (eg, fluoxetine,

Initiation of an MAOI is always based on whether the patient can reliably follow the basic dietary advice (see “A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

The orthostasis management strategy is similar to that employed for

Augmentation options for patients taking MAOIs

For depressed patients who do not achieve remission of symptoms from MAOI therapy, augmentation options should be sought, as patients who respond but fail to remit are at increased risk of relapse.26 Lithium augmentation is one of the more common strategies, with abundant data supporting its use.27,28 Case reports dating back >12 years describe the concurrent use o

1. Krishnamoorthy S, Ma Z, Zhang G, et al. Involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in the serotonin (5-HT) syndrome caused by excessive 5-HT efflux in rat brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107(4):830-841.

2. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148(6):705-713.

3. Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review concerning dietary tyramine and drug interactions. PsychoTropical Commentaries. 2016;16(6):1-90.

4. Haberzettl R, Fink H, Bert B. Role of 5-HT(1A)- and 5-HT(2A) receptors for the murine model of the serotonin syndrome. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2014;70(2):129-133.

5. Shioda K, Nisijima K, Yoshino T, et al. Mirtazapine abolishes hyperthermia in an animal model of serotonin syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2010;482(3):216-219.

6. White K, Simpson G. Combined MAOI-tricyclic antidepressant treatment: a reevaluation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(5):264-282.

7. Otte W, Birkenhager TK, van den Broek WW. Fatal interaction between tranylcypromine and imipramine. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(5):264-265.

8. Panisset M, Chen JJ, Rhyee SH, et al. Serotonin toxicity association with concomitant antidepressants and rasagiline treatment: retrospective study (STACCATO). Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(12):1250-1258.

9. Gillman PK. Mirtazapine: unable to induce serotonin toxicity? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26(6):288-289; author reply 289-290.

10. Gillman PK. A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(2):117-125.

11. Meyer JM, Cummings MA, Proctor G. Augmentation of phenelzine with aripiprazole and quetiapine in a treatment resistant patient with psychotic unipolar depression: case report and literature review. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(5):391-396.

12. Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1520-1524.

13. Israel JA. Combining stimulants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a reexamination of the literature and a report of a new treatment combination. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.15br01836.

14. Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, et al. In vitro characterization of psychoactive substances at rat, mouse, and human trace amine-associated receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357(1):134-144.

15. Froimowitz M, Gu Y, Dakin LA, et al. Slow-onset, long-duration, alkyl analogues of methylphenidate with enhanced selectivity for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):219-232.

16. Stahl SM, Felker A. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a modern guide to an unrequited class of antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(10):855-780.

17. Hiemke C, Härtter S. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85(1):11-28.

18. Pristiq [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2016.

19. Savella [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

20. Viibryd [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

21. Trintellix [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; 2016.

22. Fetzima [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2017.

23. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

24. Testani M Jr. Clozapine-induced orthostatic hypotension treated with fludrocortisone. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(11):497-498.

25. Emsam [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2015.

26. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

27. Tariot PN, Murphy DL, Sunderland T, et al. Rapid antidepressant effect of addition of lithium to tranylcypromine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6(3):165-167.

28. Kok RM, Vink D, Heeren TJ, et al. Lithium augmentation compared with phenelzine in treatment-resistant depression in the elderly: an open, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1177-1185.

29. Quante A, Zeugmann S. Tranylcypromine and bupropion combination therapy in treatment-resistant major depression: a report of 2 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(4):572-574.

30. Joffe RT. Triiodothyronine potentiation of the antidepressant effect of phenelzine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49(10):409-410.

31. Hullett FJ, Bidder TG. Phenelzine plus triiodothyronine combination in a case of refractory depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171(5):318-320.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have well-established efficacy for treating depression, panic disorder, and social phobia. However, a lack of familiarity with these agents and misconceptions about the risks associated with their use have led to MAOIs being substantially underutilized. The goal of this 2-part guide to MAOIs is to educate clinicians about this often-overlooked class of medications. Part 1 (“A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

MAOIs and potential drug interactions

One source of concern in patients receiving irreversible nonselective MAOIs is the development of excessive serotonergic neurotransmission resulting in SS. In the 1960s, researchers noted that administering large doses of

- mild symptoms: tremor, akathisia, inducible clonus

- moderate symptoms: spontaneous or sustained clonus, muscular hypertonicity

- severe symptoms: hyperthermia, diaphoresis.2

Although SS can be induced by significant exposure to individual agents that promote excess synaptic serotonin (eg, overdose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), the majority of fatal cases have occurred among patients taking MAOIs who were coadministered an agent that inhibited serotonin reuptake (Table 13). Animal studies have determined that excessive stimulation of the 5HT2A receptor is primarily responsible for SS,4 and that 5HT2A antagonists, such as mirtazapine, can block the development of SS in a mouse coadministered

Risk for SS. Most medications that promote serotonergic activity are well known for their use as antidepressants, but other agents that have 5HT reuptake properties (eg, the antihistamine chlorpheniramine) must be avoided. Although older literature suggests that the use of lower doses of certain tricyclic antidepressants concurrently with MAOIs may not be as dangerous as once believed,6 there are sufficient reports of serious outcomes that tricyclics should be avoided in patients taking MAOIs because of the risk of SS, and also because, in general, tricyclics are poorly tolerated.7

Desipramine, a potent norepinephrine transporter (NET) inhibitor, blocks the entry of tyramine into cells by NET, thereby preventing hypertensive events in animal models of tyramine overexposure. However, in some assays, the affinity for the serotonin transporter is not insignificant, so at higher doses desipramine may pose the same theoretical risk for SS as seen with other tricyclics.3

Lastly

Astute clinicians will recognize that antidepressants that lack 5HT reuptake (eg, bupropion, mirtazapine) are not on this list of agents that may increase SS risk when taken with an MAOI. Older papers often list mirtazapine, but as a 5HT2A antagonist, it does not possess a plausible mechanism by which it can induce 5HT toxicity.9,10 Most atypical antipsychotics have significant 5HT2A antagonism and can be combined with MAOIs, but ziprasidone is an exception: as a moderate SNRI, it has been associated with SS when administered with an MAOI.11

Pressor reactions. The only theoretical sources of concern for pressor effects are medications that act as norepinephrine releasers through interactions at the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) (for more information on TAAR1, see

Starting a patient on an MAOI

Contraindicated medications need to be tapered before beginning MAOI treatment. The duration of the washout period depends on the half-life of the medication and any active metabolites. Antidepressants with half-lives of approximately ≤24 hours should be tapered over 7 to 14 days (depending on the dose) to minimize the risk of withdrawal syndromes, while those with long half-lives (eg, fluoxetine,

Initiation of an MAOI is always based on whether the patient can reliably follow the basic dietary advice (see “A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

The orthostasis management strategy is similar to that employed for

Augmentation options for patients taking MAOIs

For depressed patients who do not achieve remission of symptoms from MAOI therapy, augmentation options should be sought, as patients who respond but fail to remit are at increased risk of relapse.26 Lithium augmentation is one of the more common strategies, with abundant data supporting its use.27,28 Case reports dating back >12 years describe the concurrent use o

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have well-established efficacy for treating depression, panic disorder, and social phobia. However, a lack of familiarity with these agents and misconceptions about the risks associated with their use have led to MAOIs being substantially underutilized. The goal of this 2-part guide to MAOIs is to educate clinicians about this often-overlooked class of medications. Part 1 (“A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

MAOIs and potential drug interactions

One source of concern in patients receiving irreversible nonselective MAOIs is the development of excessive serotonergic neurotransmission resulting in SS. In the 1960s, researchers noted that administering large doses of

- mild symptoms: tremor, akathisia, inducible clonus

- moderate symptoms: spontaneous or sustained clonus, muscular hypertonicity

- severe symptoms: hyperthermia, diaphoresis.2

Although SS can be induced by significant exposure to individual agents that promote excess synaptic serotonin (eg, overdose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]), the majority of fatal cases have occurred among patients taking MAOIs who were coadministered an agent that inhibited serotonin reuptake (Table 13). Animal studies have determined that excessive stimulation of the 5HT2A receptor is primarily responsible for SS,4 and that 5HT2A antagonists, such as mirtazapine, can block the development of SS in a mouse coadministered

Risk for SS. Most medications that promote serotonergic activity are well known for their use as antidepressants, but other agents that have 5HT reuptake properties (eg, the antihistamine chlorpheniramine) must be avoided. Although older literature suggests that the use of lower doses of certain tricyclic antidepressants concurrently with MAOIs may not be as dangerous as once believed,6 there are sufficient reports of serious outcomes that tricyclics should be avoided in patients taking MAOIs because of the risk of SS, and also because, in general, tricyclics are poorly tolerated.7

Desipramine, a potent norepinephrine transporter (NET) inhibitor, blocks the entry of tyramine into cells by NET, thereby preventing hypertensive events in animal models of tyramine overexposure. However, in some assays, the affinity for the serotonin transporter is not insignificant, so at higher doses desipramine may pose the same theoretical risk for SS as seen with other tricyclics.3

Lastly

Astute clinicians will recognize that antidepressants that lack 5HT reuptake (eg, bupropion, mirtazapine) are not on this list of agents that may increase SS risk when taken with an MAOI. Older papers often list mirtazapine, but as a 5HT2A antagonist, it does not possess a plausible mechanism by which it can induce 5HT toxicity.9,10 Most atypical antipsychotics have significant 5HT2A antagonism and can be combined with MAOIs, but ziprasidone is an exception: as a moderate SNRI, it has been associated with SS when administered with an MAOI.11

Pressor reactions. The only theoretical sources of concern for pressor effects are medications that act as norepinephrine releasers through interactions at the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) (for more information on TAAR1, see

Starting a patient on an MAOI

Contraindicated medications need to be tapered before beginning MAOI treatment. The duration of the washout period depends on the half-life of the medication and any active metabolites. Antidepressants with half-lives of approximately ≤24 hours should be tapered over 7 to 14 days (depending on the dose) to minimize the risk of withdrawal syndromes, while those with long half-lives (eg, fluoxetine,

Initiation of an MAOI is always based on whether the patient can reliably follow the basic dietary advice (see “A concise guide to monoamine inhibitors,”

The orthostasis management strategy is similar to that employed for

Augmentation options for patients taking MAOIs

For depressed patients who do not achieve remission of symptoms from MAOI therapy, augmentation options should be sought, as patients who respond but fail to remit are at increased risk of relapse.26 Lithium augmentation is one of the more common strategies, with abundant data supporting its use.27,28 Case reports dating back >12 years describe the concurrent use o

1. Krishnamoorthy S, Ma Z, Zhang G, et al. Involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in the serotonin (5-HT) syndrome caused by excessive 5-HT efflux in rat brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107(4):830-841.

2. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148(6):705-713.

3. Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review concerning dietary tyramine and drug interactions. PsychoTropical Commentaries. 2016;16(6):1-90.

4. Haberzettl R, Fink H, Bert B. Role of 5-HT(1A)- and 5-HT(2A) receptors for the murine model of the serotonin syndrome. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2014;70(2):129-133.

5. Shioda K, Nisijima K, Yoshino T, et al. Mirtazapine abolishes hyperthermia in an animal model of serotonin syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2010;482(3):216-219.

6. White K, Simpson G. Combined MAOI-tricyclic antidepressant treatment: a reevaluation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(5):264-282.

7. Otte W, Birkenhager TK, van den Broek WW. Fatal interaction between tranylcypromine and imipramine. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(5):264-265.

8. Panisset M, Chen JJ, Rhyee SH, et al. Serotonin toxicity association with concomitant antidepressants and rasagiline treatment: retrospective study (STACCATO). Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(12):1250-1258.

9. Gillman PK. Mirtazapine: unable to induce serotonin toxicity? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26(6):288-289; author reply 289-290.

10. Gillman PK. A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(2):117-125.

11. Meyer JM, Cummings MA, Proctor G. Augmentation of phenelzine with aripiprazole and quetiapine in a treatment resistant patient with psychotic unipolar depression: case report and literature review. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(5):391-396.

12. Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1520-1524.

13. Israel JA. Combining stimulants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a reexamination of the literature and a report of a new treatment combination. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.15br01836.

14. Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, et al. In vitro characterization of psychoactive substances at rat, mouse, and human trace amine-associated receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357(1):134-144.

15. Froimowitz M, Gu Y, Dakin LA, et al. Slow-onset, long-duration, alkyl analogues of methylphenidate with enhanced selectivity for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):219-232.

16. Stahl SM, Felker A. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a modern guide to an unrequited class of antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(10):855-780.

17. Hiemke C, Härtter S. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85(1):11-28.

18. Pristiq [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2016.

19. Savella [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

20. Viibryd [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

21. Trintellix [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; 2016.

22. Fetzima [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2017.

23. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

24. Testani M Jr. Clozapine-induced orthostatic hypotension treated with fludrocortisone. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(11):497-498.

25. Emsam [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2015.

26. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

27. Tariot PN, Murphy DL, Sunderland T, et al. Rapid antidepressant effect of addition of lithium to tranylcypromine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6(3):165-167.

28. Kok RM, Vink D, Heeren TJ, et al. Lithium augmentation compared with phenelzine in treatment-resistant depression in the elderly: an open, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1177-1185.

29. Quante A, Zeugmann S. Tranylcypromine and bupropion combination therapy in treatment-resistant major depression: a report of 2 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(4):572-574.

30. Joffe RT. Triiodothyronine potentiation of the antidepressant effect of phenelzine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49(10):409-410.

31. Hullett FJ, Bidder TG. Phenelzine plus triiodothyronine combination in a case of refractory depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171(5):318-320.

1. Krishnamoorthy S, Ma Z, Zhang G, et al. Involvement of 5-HT2A receptors in the serotonin (5-HT) syndrome caused by excessive 5-HT efflux in rat brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107(4):830-841.

2. Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148(6):705-713.

3. Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review concerning dietary tyramine and drug interactions. PsychoTropical Commentaries. 2016;16(6):1-90.

4. Haberzettl R, Fink H, Bert B. Role of 5-HT(1A)- and 5-HT(2A) receptors for the murine model of the serotonin syndrome. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2014;70(2):129-133.

5. Shioda K, Nisijima K, Yoshino T, et al. Mirtazapine abolishes hyperthermia in an animal model of serotonin syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2010;482(3):216-219.

6. White K, Simpson G. Combined MAOI-tricyclic antidepressant treatment: a reevaluation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(5):264-282.

7. Otte W, Birkenhager TK, van den Broek WW. Fatal interaction between tranylcypromine and imipramine. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(5):264-265.

8. Panisset M, Chen JJ, Rhyee SH, et al. Serotonin toxicity association with concomitant antidepressants and rasagiline treatment: retrospective study (STACCATO). Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(12):1250-1258.

9. Gillman PK. Mirtazapine: unable to induce serotonin toxicity? Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26(6):288-289; author reply 289-290.

10. Gillman PK. A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(2):117-125.

11. Meyer JM, Cummings MA, Proctor G. Augmentation of phenelzine with aripiprazole and quetiapine in a treatment resistant patient with psychotic unipolar depression: case report and literature review. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(5):391-396.

12. Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1520-1524.

13. Israel JA. Combining stimulants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a reexamination of the literature and a report of a new treatment combination. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.15br01836.

14. Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, et al. In vitro characterization of psychoactive substances at rat, mouse, and human trace amine-associated receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357(1):134-144.

15. Froimowitz M, Gu Y, Dakin LA, et al. Slow-onset, long-duration, alkyl analogues of methylphenidate with enhanced selectivity for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 2007;50(2):219-232.

16. Stahl SM, Felker A. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a modern guide to an unrequited class of antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(10):855-780.

17. Hiemke C, Härtter S. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85(1):11-28.

18. Pristiq [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2016.

19. Savella [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

20. Viibryd [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2016.

21. Trintellix [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; 2016.

22. Fetzima [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA Inc; 2017.

23. Nardil [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2009.

24. Testani M Jr. Clozapine-induced orthostatic hypotension treated with fludrocortisone. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(11):497-498.

25. Emsam [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Somerset Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2015.

26. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

27. Tariot PN, Murphy DL, Sunderland T, et al. Rapid antidepressant effect of addition of lithium to tranylcypromine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6(3):165-167.

28. Kok RM, Vink D, Heeren TJ, et al. Lithium augmentation compared with phenelzine in treatment-resistant depression in the elderly: an open, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1177-1185.

29. Quante A, Zeugmann S. Tranylcypromine and bupropion combination therapy in treatment-resistant major depression: a report of 2 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(4):572-574.

30. Joffe RT. Triiodothyronine potentiation of the antidepressant effect of phenelzine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49(10):409-410.

31. Hullett FJ, Bidder TG. Phenelzine plus triiodothyronine combination in a case of refractory depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171(5):318-320.