User login

“This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s about decency. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency . ”

– Albert Camus, La Peste (1947)1

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1 swine flu, Ebola, Zika, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): the 21st century has already been witness to several serious infectious outbreaks and pandemics,2 but none has been as deadly and consequential as the current one. The ongoing SARS-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is shaping not only current psychiatric care but the future of psychiatry. Now that we are beyond the initial stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when psychiatrists had a crash course in disaster psychiatry, our attention must shift to rebuilding and managing disillusionment and other psychological fallout of the intense early days.3

In this article, we offer guidance to psychiatrists caring for patients with serious mental illness (SMI) during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Patients with SMI are easily forgotten as other issues (eg, preserving ICU capacity) overshadow the already historically neglected needs of this impoverished group.4 From both human and public-health perspectives, this inattention is a mistake. Assuring psychiatric stability is critically important to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in marginalized communities comprised of individuals who are poor, members of racial minorities, and others who already experience health disparities.5 Without controlling transmission in these groups, the pandemic will not be sufficiently contained.

We begin by highlighting general principles of pandemic management because caring for patients with SMI does not occur in a vacuum. Infectious outbreaks require not only helping those who need direct medical care because they are infected, but also managing populations that are at risk of getting infected, including health care and other essential workers.

Principles of pandemic management

Delivery of medical care during a pandemic differs from routine care. An effective disaster response requires collaboration and coordination among public-health, treatment, and emergency systems. Many institutions shift to an incident management system and crisis leadership, with clear lines of authority to coordinate responders and build medical surge capacity. Such a top-down leadership approach must plan and allow for the emergence of other credible leaders and for the restoration of people’s agency.

Unfortunately, adaptive capacity may be limited, especially in the public sector and psychiatric care system, where resources are already poor. Particularly early in a pandemic, services considered non-essential—which includes most psychiatric outpatient care—can become unavailable. A major effort is needed to prevent the psychiatric care system from contracting further, as happened during 9/11.6 Additionally, “essential” cannot be conflated with “emergent,” as can easily occur in extreme circumstances. Early and sustained efforts are required to ensure that patients with SMI who may be teetering on the edge of emergency status do not slip off that edge, especially when the emergency medical system is operating over capacity.

A comprehensive outbreak response must consider that a pandemic is not only a medical crisis but a mental health crisis and a communication emergency.7 Mental health clinicians need to provide accurate information and help patients cope with their fears.

Continue to: Psychological aspects of pandemics

Psychological aspects of pandemics. Previous infectious outbreaks have reaffirmed that mental health plays an outsized role during epidemics. Chaos, uncertainty, fear of death, and loss of income and housing cause prolonged stress and exact a psychological toll.

Adverse psychological impacts include expectable, normal reactions such as stress-induced anxiety or insomnia. In addition, new-onset psychiatric illnesses or exacerbations of existing ones may emerge.8 As disillusionment and demoralization appear in the wake of the acute phase, with persistently high unemployment, suicide prevention becomes an important goal.9

Pandemics lead to expectable behavioral responses (eg, increases in substance use and interpersonal conflict). Fear-based decisions may result in unhelpful behavior, such as hoarding medications (which may result in shortages) or dangerous, unsupervised use of unproven medications (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Trust is needed to accept public-health measures, and recommendations (eg, wearing masks) must be culturally informed to be credible and effective.

Because people are affected differently, at individual, cultural, and socioeconomic levels, they will view the situation differently. For many people, secondary stressors (eg, job loss) may be more disastrous than the primary medical event (ie, the pandemic). This distinction is critical because concrete financial help, not psychiatric care, is needed. Sometimes, even when a psychiatric disorder such as SMI or major neurocognitive disorder is present, the illusion of an acute decompensation can be created by the loss of social and structural supports that previously scaffolded a person’s life.

Mental illness prevention. Community mental-health surveillance is important to monitor for distress, psychiatric symptoms, health-risk behaviors, risk and safety perception, and preparedness. Clinicians must be ready to normalize expectable and temporary distress, while recognizing when that distress becomes pathological. This may be difficult in patients with SMI who often already have reduced stress tolerance or problem-based coping skills.10

Continue to: Psychological first aid...

Psychological first aid (PFA) is a standard intervention recommended by the World Health Organization for most individuals following a disaster; it is evidence-informed and has face validity.11 Intended to relieve distress by creating an environment that is safe, calm, and connected, PFA fosters self-efficacy and hope. While PFA is a form of universal prevention, it is not designed for patients with SMI, is not a psychiatric intervention, and is not provided by clinicians. Its principles, however, can easily be applied to patients with SMI to prevent distressing symptoms from becoming a relapse.

Communication. Good risk and crisis communication are critical because individual and population behavior will be governed by the perception of risk and fear, and not by facts. Failure to manage the “infodemic”7—with its misinformation, contradictory messages, and rumors—jeopardizes infection control if patients become paralyzed by uncertainty and fear. Scapegoating occurs easily during times of threat, and society must contain the parallel epidemic of xenophobia based on stigma and misinformation.12

Decision-making under uncertainty is not perfect and subject to revision as better information becomes available. Pointing this out to the public is delicate but essential to curtail skepticism and mistrust when policies are adjusted in response to new circumstances and knowledge.

Mistrust of an authority’s legitimacy and fear-based decisions lead to lack of cooperation with public-health measures, which can undermine an effective response to the pandemic. Travel restrictions or quarantine measures will not be followed if individuals question their importance. Like the general public, patients need education and clear communication to address their fear of contagion, dangers posed to family (and pets), and mistrust of authority and government. A lack of appreciation of the seriousness of the pandemic and individual responsibility may need to be addressed. Two important measures to accomplish this are steering patients to reputable sources of information and advising that they limit media exposure.

Resilience-building. Community and workplace resilience are important aspects of making it through a disaster as best as possible. Resilience is not innate and fixed; it must be deliberately built.13 Choosing an attitude of post-traumatic growth over the victim narrative is a helpful stance. Practicing self-care (rest, nutrition, exercise) and self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness) is good advice for patients and caregivers alike.

Continue to: Workforce protection

Workforce protection. Compared to other disasters, infectious outbreaks disproportionally affect the medical community, and care delivery is at stake. While psychological and psychiatric needs may increase during a pandemic, services often contract, day programs and clinics close, teams are reduced to skeleton crews, and only emergency psychiatric care is available. Workforce protection is critical to avoid illness or simple absenteeism due to mistrust of protective measures.

Only a well-briefed, well-led, well-supported, and adequately resourced workforce is going to be effective in managing this public-health emergency. Burnout and moral injury are feared long-term consequences for health care workers that need to be proactively addressed.14 As opposed to other forms of disasters, managing your own fears about safety is important. Clinicians and their patients sit in the proverbial same boat.

Ethics. The anticipated need to ration life-saving care (eg, ventilators) has been at the forefront of ethical concerns.15 In psychiatry, the question of involuntary public-health interventions for uncooperative psychiatric patients sits uncomfortably between public-health ethics and human rights, and is an opportunity for collaboration with public-health and infectious-disease colleagues.

Redeployed clinicians and those working under substandard conditions may be concerned about civil liability due to a modified standard of care during a crisis. Some clinicians may ask if their duty to care must override their natural instinct to protect themselves. There is a lot of room for resentment in these circumstances. Redeployed or otherwise “conscripted” clinicians may resent administrators, especially those administering from the safety of their homes. Those “left behind” to work in potentially precarious circumstances may resent their absent colleagues. Moreover, these front-line clinicians may have been forced to make ethical decisions for which they were not prepared.16 Maintaining morale is far from trivial, not just during the pandemic, but afterward, when (and if) the entire workforce is reunited. All parties need to be mindful of how their actions and decisions impact and are perceived by others, both in the hospital and at home.

Managing patients with SMI during COVID-19

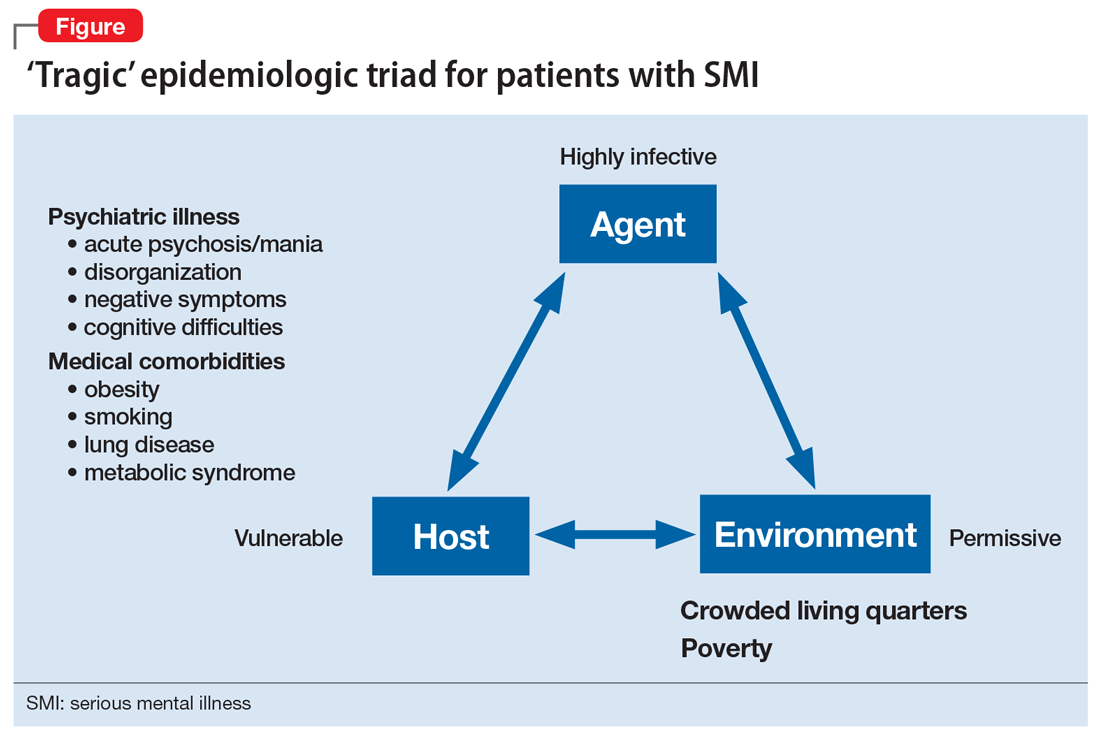

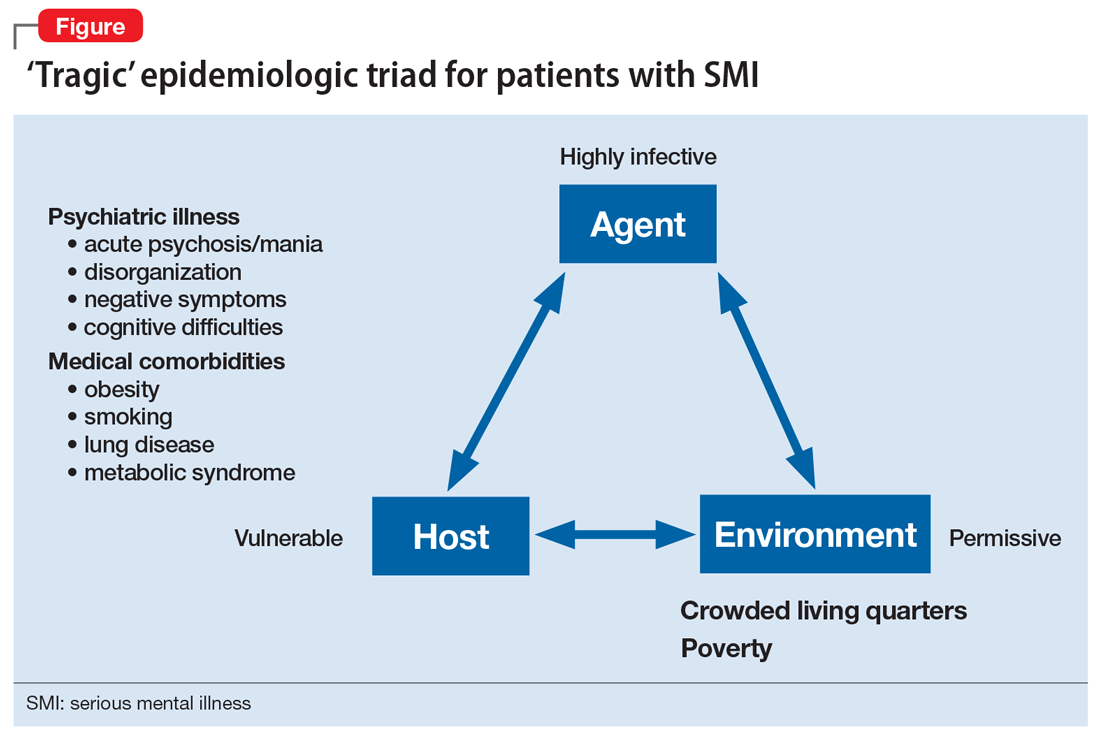

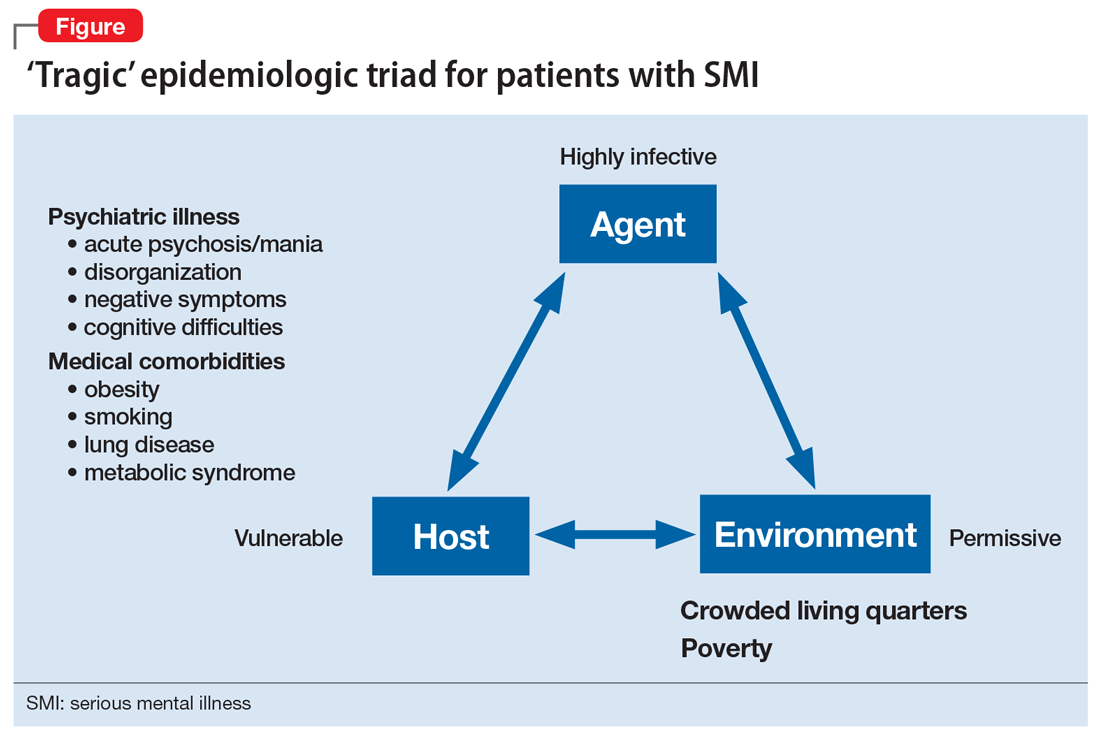

Patients with SMI are potentially hard hit by COVID-19 due to a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment: SARS-CoV-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting patients with SMI who are vulnerable hosts in permissive environments (Figure).

Continue to: While not as infectious as measles...

While not as infectious as measles, COVID-19 is more infectious than the seasonal flu virus.17 It can lead to uncontrolled infection within a short period of time, particularly in enclosed settings. Outbreaks have occurred readily on cruise ships and aircraft carriers as well as in nursing homes, homeless shelters, prisons, and group homes.

Patients with SMI are vulnerable hosts because they have many of the medical risk factors18 that portend a poor prognosis if they become infected, including pre-existing lung conditions and heart disease19 as well as diabetes and obesity.20 Obesity likely creates a hyperinflammatory state and a decrease in vital capacity. Patient-related behavioral factors include poor early-symptom reporting and ineffective infection control.

Unfavorable social determinants of health include not only poverty but crowded housing that is a perfect incubator for COVID-19.

Priority treatment goals. The overarching goal during a pandemic is to keep patients with SMI in psychiatric treatment and prevent them from disengaging from care in the service of infection control. Urgent tasks include infection control, relapse prevention, and preventing treatment disengagement and loneliness.

Infection control. As trusted sources of information, psychiatrists can play an important role in infection control in several important ways:

- educating patients about infection-control measures and public-health recommendations

- helping patients understand what testing can accomplish and when to pursue it

- encouraging protective health behaviors (eg, hand washing, mask wearing, physical distancing)

- assessing patients’ risk appreciation

- assessing for and addressing obstacles to implementing and complying with infection-control measures

- explaining contact tracing

- providing reassurance.

Continue to: Materials and explanations...

Materials and explanations must be adapted for patient understanding.

Patients with disorganization or cognitive disturbances may have difficulties cooperating or problem-solving. Patients with negative symptoms may be inappropriately unconcerned and also inaccurately report symptoms that suggest COVID-19. Acute psychosis or mania can prevent patients from complying with public-health efforts. Some measures may be difficult to implement if the means are simply not there (eg, physical distancing in a crowded apartment). Previously open settings (eg, group homes) have had to develop new mechanisms under the primacy of infection control. Inpatient units—traditionally places where community, shared healing, and group therapy are prized—have had to decrease maximum occupancy, limit the number of patients attending groups, and discourage or outrightly prohibit social interaction (eg, dining together).

Relapse prevention. Patients who take maintenance medications need to be supported. A manic or psychotic relapse during a pandemic puts patients at risk of acquiring and spreading COVID-19. “Treatment as prevention” is a slogan from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care that captures the importance of antiretroviral treatment to prevent medical complications from HIV, and also to reduce infecting other people. By analogy, psychiatric treatment for patients with SMI can prevent psychiatric instability and thereby control viral transmission. Avoiding sending psychiatric patients to a potentially stressed acute-care system is important.

Psychosocial support. Clinics need to ensure that patients continue to engage in care beyond medication-taking to proactively prevent psychiatric exacerbations. Healthful, resilience-building behaviors should be encouraged while monitoring and counseling against maladaptive ones (eg, increased substance use). Supporting patients emotionally and helping them solve problems are critical, particularly for those who are subjected to quarantine or isolation. Obviously, in these latter situations, outreach will be necessary and may require creative delivery systems and dedicated clinicians for patients who lack access to the technology necessary for virtual visits. Havens and Ghaemi21 have suggested that a good therapeutic alliance can be viewed as a mood stabilizer. Helping patients grieve losses (loved ones, jobs, sense of safety) may be an important part of support.

Even before COVID-19, loneliness was a major factor for patients with schizophrenia.22 A psychiatric clinic is one aspect of a person with SMI’s social network; during the initial phase of the pandemic, many clinics and treatment programs closed. Patients for whom clinics structure and anchor their activities are at high risk of disconnecting from treatment, staying at home, and becoming lonely.

Continue to: Caregivers are always important...

Caregivers are always important to SMI patients, but they may assume an even bigger role during this pandemic. Some patients may have moved in with a relative, after years of living on their own. In other cases, stable caregiver relationships may be disrupted due to COVID-19–related sickness in the caregiver; if not addressed, this can result in a patient’s clinical decompensation. Clinicians should take the opportunity to understand who a patient’s caregivers are (group home staff, families) and rekindle clinical contact with them. Relationships with caregivers that may have been on “autopilot” during normal times are opportunities for welcome support and guidance, to the benefit of both patients and caregivers.

Table 1 summarizes clinical tasks that need to be kept in mind when conducting clinic visits during COVID-19 in order to achieve the high-priority treatment goals of infection control, relapse prevention, and psychosocial support.

Differential diagnosis. Neuropsychiatric syndromes have long been observed in influenza pandemics,23 due both to direct viral effects and to the effects of critical illness on the brain. Two core symptoms of COVID-19—anosmia and ageusia—suggest that COVID-19 can directly affect the brain. While neurologic manifestations are common,24 it remains unclear to what extent COVID-19 can directly “cause” psychiatric symptoms, or if such symptoms are the result of cytokines25 or other medical processes (eg, thromboembolism).26 Psychosis due to COVID-19 may, in some cases, represent a stress-related brief psychotic disorder.27

Hospitalized patients who have recovered from COVID-19 may have experienced prolonged sedation and severe delirium in an ICU.28 Complications such as posttraumatic stress disorder,29 hypoperfusion-related brain injuries, or other long-term cognitive difficulties may result. In previous flu epidemics, patients developed serious neurologic complications such as post-encephalitic Parkinson’s disease.30

Any person subjected to isolation or quarantine is at risk for psychiatric complications.31 Patients with SMI who live in group homes may be particularly susceptible to new rules, including no-visitor policies.

Continue to: Outpatients whose primary disorder...

Outpatients whose primary disorder is well controlled may, like anyone else, struggle with the effects of the pandemic. It is necessary to carefully differentiate non-specific symptoms associated with stress from the emergence of a new disorder resulting from stress.32 For some patients, grief or adjustment disorders should be considered. Prolonged stress and uncertainty may eventually lead to an exacerbation of a primary disorder, particularly if the situation (eg, financial loss) does not improve or worsens. Demoralization and suicidal thinking need to be monitored. Relapse or increased use of alcohol or other substances as a response to stress may also complicate the clinical picture.33 Last, smoking cessation as a major treatment goal in general should be re-emphasized and not ignored during the ongoing pandemic.34

Table 2 summarizes psychiatric symptoms that need to be considered when managing a patient with SMI during this pandemic.

Treatment tools

Psychopharmacology. Even though crisis-mode prescribing may be necessary, the safe use of psychotropics remains the goal of psychiatric prescribing. Access to medications becomes a larger consideration; for many patients, a 90-day supply may be indicated. Review of polypharmacy, including for pneumonia risk, should be undertaken. Preventing drooling (eg, from sedation, clozapine, extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) will decrease aspiration risk.

In general, treatment of psychiatric symptoms in a patient with COVID-19 follows usual guidelines. The best treatment for COVID-19 patients with delirium, however, remains to be established, particularly how to manage severe agitation.28 Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions between psychotropics and antiviral treatments for COVID-19 (eg, QTc prolongation) can be expected and need to be reviewed.35 For stress-related anxiety, judicious pharmacotherapy can be helpful. Diazepam given at the earliest signs of a psychotic relapse may stave off a relapse for patients with schizophrenia.36 Even if permitted under relaxed prescribing rules during a public-health emergency, prescribing controlled substances without seeing patients in person requires additional thought. In some cases, adjusting the primary medication to buffer against stress may be preferred (eg, adjusting an antipsychotic in a patient on maintenance treatment for schizophrenia, particularly if a low-dose strategy is pursued).

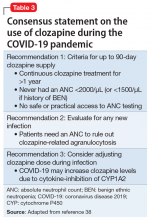

Clozapine requires registry-based prescribing and bloodwork (“no blood, no drug”). The use of clozapine during this public-health emergency has been made easier because of FDA guidance that allows clozapine to be dispensed without blood work if obtaining blood work is not possible (eg, a patient is quarantined) or can be accomplished only at substantial risk to patients and the population at large. Under certain conditions, clozapine can be dispensed safely and in a way that is consistent with infection prevention. Clozapine-treated patients admitted with COVID-19 should be monitored for clozapine toxicity and the clozapine dose adjusted.37 A consensus statement consistent with the FDA and clinical considerations for using clozapine during COVID-19 is summarized in Table 3.38

Continue to: Long-acting injectable antipsychotics...

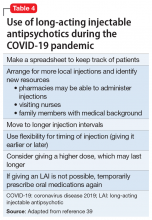

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) pose a problem because they require in-person visits. Ideally, during a pandemic, patients should be seen in person as frequently as medically necessary but as infrequently as possible to limit exposure of both patients and staff. Table 4 provides some clinical recommendations on how to use LAIs during the pandemic.39

Supportive psychotherapy may be the most important tool we have in helping patients with loss and uncertainty during these challenging months.40 Simply staying in contact with patients plays a major role in preventing care discontinuity. Even routine interactions have become stressful, with everyone wearing a mask that partially obscures the face. People with impaired hearing may find it even more difficult to understand you.

Education, problem-solving, and a directive, encouraging style are major tools of supportive psychotherapy to reduce symptoms and increase adaptive skills. Clarify that social distancing refers to physical, not emotional, distancing. The judicious and temporary use of anxiolytics is appropriate to reduce anxiety. Concrete help and problem-solving (eg, filling out forms) are examples of proactive crisis intervention.

Telepsychiatry emerged in the pandemic’s early days as the default mode of practice in order to limit in-person contacts.41 Like all new technology, telepsychiatry brings progress and peril.42 While it has gone surprisingly well for most, the “digital divide” does not afford all patients access to the needed technology. The long-term effectiveness and acceptance of telehealth remain to be seen. (Editor’s Note: For more about this topic, see “Telepsychiatry: What you need to know.”

Lessons learned and outlook

Infectious outbreaks have historically inflicted long-term disruptions on societies and altered the course of history. However, each disaster is unique, and lessons from previous disasters may only partially apply.43 We do not yet know how this one will end, including how long it will take for the world’s economies to recover. If nothing else, the current public-health emergency has brought to the forefront what psychiatrists have always known: health disparities are partially responsible for different disease risks (in this case, the risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2).5 It may not be a coincidence that the Black Lives Matter movement is becoming a major impetus for social change at a time when the pandemic is exposing health-care inequalities.

Continue to: Some areas of the country...

Some areas of the country succeeded in reducing infections and limiting community spread, which ushered in an uneasy sense of normalcy even while the pandemic continues. At least for now, these locales can focus on rebuilding and preparing for expectable fluctuations in disease activity, including the arrival of the annual flu season on top of COVID-19.44 Recovery is not a return to the status quo ante but building stronger communities—“building back better.”45 Unless there is a continuum of care, shortcomings in one sector will have ripple effects through the entire system, particularly for psychiatric care for patients with SMI, which was inadequate before the pandemic.

Ensuring access to critical care was a priority during the pandemic’s early phase but came at the price of deferring other types of care, such as routine primary care; the coming months will see the downstream consequences of this approach,46 including for patients with SMI.

In the meantime, doing our job as clinicians, as Camus’s fictitious Dr. Bernard Rieux from the epigraph responds when asked how to define decency, may be the best we can do in these times. This includes contributing to and molding our field’s future and fostering a sense of agency in our patients and in ourselves. Major goals will be to preserve lessons learned, maintain flexibility, and avoid a return to unhelpful overregulation and payment models that do not reflect the flexible, person-centered care so important for patients with SMI.47

Bottom Line

During a pandemic, patients with serious mental illness may be easily forgotten as other issues overshadow the needs of this impoverished group. During a pandemic, the priority treatment goals for these patients are infection control, relapse prevention, and preventing treatment disengagement and loneliness. A pandemic requires changes in how patients with serious mental illness will receive psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.

Related Resources

- Huremović D (ed). Psychiatry of pandemics: a mental health response to infection outbreak. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2019.

- Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Weisaeth L, et al (eds). Textbook of disaster psychiatry. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. Coronavirus resources. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus.

- SMI Adviser. Make informed decisions related to COVID-19 and mental health. https://smiadviser.org/about/covid.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Diazepam • Valium

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

1. Camus A. La peste. Paris, France: Éditions Gallimard; 1947.

2. Huremovic

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Phases of disaster. https://www.samhsa.gov/dtac/recovering-disasters/phases-disaster. Updated June 17, 2020. Accessed August 7, 2020.

4. Geller J. COVID-19 and advocacy—the good and the unacceptable. Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2020.5b13. Published May 7, 2020. Accessed August 7, 2020.

5. Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Perez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467.

6. Sederer LI, Lanzara CB, Essock SM, et al. Lessons learned from the New York State mental health response to the September 11, 2001, attacks. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(9):1085-1089.

7. World Health Organization. Infodemic management – infodemiology. https://www.who.int/teams/risk-communication/infodemic-management. Accessed August 7, 2020.

8. Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, et al. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;117(7):574-575.

9. Kawohl W, Nordt C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):389-390.

10. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0.

11. Minihan E, Gavin B, Kelly BD, et al. Covid-19, mental health and psychological first aid. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020:1-12.

12. Adja KYC, Golinelli D, Lenzi J, et al. Pandemics and social stigma: who’s next? Italy’s experience with COVID-19. Public Health. 2020;185:39-41.

13. Rosenberg AR. Cultivating deliberate resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic [published online April 14, 2020]. JAMA Pediatr. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1436.

14. Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress [published online January 31, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21576.

15. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055.

16. Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy - ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1873-1875.

17. Viceconte G, Petrosillo N. COVID-19 R0: magic number or conundrum? Infect Dis Rep. 2020;12(1):8516.

18. de Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, van Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):15-22.

19. Chen R, Liang W, Jiang M, et al. Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest. 2020;158(1):97-105.

20. Finer N, Garnett SP, Bruun JM. COVID-19 and obesity. Clin Obes. 2020;10(3):e12365. doi: 10.1111/cob.12365.

21. Havens LL, Ghaemi SN. Existential despair and bipolar disorder: the therapeutic alliance as a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychother. 2005;59(2):137-147.

22. Trémeau F, Antonius D, Malaspina D, et al. Loneliness in schizophrenia and its possible correlates. An exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:211-217.

23. Menninger KA. Psychoses associated with influenza: I. General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72(4):235-241.

24. Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413:116832. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116832.

25. Ferrando SJ, Klepacz L, Lynch S, et al. COVID-19 psychosis: a potential new neuropsychiatric condition triggered by novel coronavirus infection and the inflammatory response? [published online May 19, 2020]. Psychosomatics. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.012.

26. Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34-39.

27. Martin Jr. EB. Brief psychotic disorder triggered by fear of coronavirus? Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/brief-psychotic-disorder-triggered-fear-coronavirus-small-case-series. Published May 8, 2020. Accessed August 7, 2020.

28. Sher Y, Rabkin B, Maldonado JR, et al. COVID-19-associated hyperactive intensive care unit delirium with proposed pathophysiology and treatment: a case report [published online May 19, 2020]. Psychosomatics. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.007.

29. Wolters AE, Peelen LM, Welling MC, et al. Long-term mental health problems after delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(10):1808-1813.

30. Toovey S. Influenza-associated central nervous system dysfunction: a literature review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2008;6(3):114-124.

31. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920.

32. Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, et al. Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):198-206.

33. Ornell F, Moura HF, Scherer JN, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113096. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113096.

34. Berlin I, Thomas D, Le Faou AL, Cornuz J. COVID-19 and smoking [published online April 3, 2020]. Nicotine Tob Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa059.

35. Back D, Marzolini C, Hodge C, et al. COVID-19 treatment in patients with comorbidities: awareness of drug-drug interactions [published online May 8, 2020]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14358.

36. Carpenter WT Jr., Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Diazepam treatment of early signs of exacerbation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(2):299-303.

37. Dotson S, Hartvigsen N, Wesner T, et al. Clozapine toxicity in the setting of COVID-19 [published online May 30, 2020]. Psychosomatics. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.025.

38. Siskind D, Honer WG, Clark S, et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(3):222-223.

39. Schnitzer K, MacLaurin S, Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. In press.

40. Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H. Learning supportive psychotherapy: an illustrated guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012.

41. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681.

42. Jordan A, Dixon LB. Considerations for telepsychiatry service implementation in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(6):643-644.

43. DePierro J, Lowe S, Katz C. Lessons learned from 9/11: mental health perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:113024.

44. Hussain S. Immunization and vaccination. In: Huremovic

45. Epping-Jordan JE, van Ommeren M, Ashour HN, et al. Beyond the crisis: building back better mental health care in 10 emergency-affected areas using a longer-term perspective. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9:15.

46. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2368-2371.

47. Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, et al. COVID-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness [published online June 3, 2020]. Psychiatr Serv. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000244.

“This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s about decency. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency . ”

– Albert Camus, La Peste (1947)1

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1 swine flu, Ebola, Zika, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): the 21st century has already been witness to several serious infectious outbreaks and pandemics,2 but none has been as deadly and consequential as the current one. The ongoing SARS-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is shaping not only current psychiatric care but the future of psychiatry. Now that we are beyond the initial stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when psychiatrists had a crash course in disaster psychiatry, our attention must shift to rebuilding and managing disillusionment and other psychological fallout of the intense early days.3

In this article, we offer guidance to psychiatrists caring for patients with serious mental illness (SMI) during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Patients with SMI are easily forgotten as other issues (eg, preserving ICU capacity) overshadow the already historically neglected needs of this impoverished group.4 From both human and public-health perspectives, this inattention is a mistake. Assuring psychiatric stability is critically important to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in marginalized communities comprised of individuals who are poor, members of racial minorities, and others who already experience health disparities.5 Without controlling transmission in these groups, the pandemic will not be sufficiently contained.

We begin by highlighting general principles of pandemic management because caring for patients with SMI does not occur in a vacuum. Infectious outbreaks require not only helping those who need direct medical care because they are infected, but also managing populations that are at risk of getting infected, including health care and other essential workers.

Principles of pandemic management

Delivery of medical care during a pandemic differs from routine care. An effective disaster response requires collaboration and coordination among public-health, treatment, and emergency systems. Many institutions shift to an incident management system and crisis leadership, with clear lines of authority to coordinate responders and build medical surge capacity. Such a top-down leadership approach must plan and allow for the emergence of other credible leaders and for the restoration of people’s agency.

Unfortunately, adaptive capacity may be limited, especially in the public sector and psychiatric care system, where resources are already poor. Particularly early in a pandemic, services considered non-essential—which includes most psychiatric outpatient care—can become unavailable. A major effort is needed to prevent the psychiatric care system from contracting further, as happened during 9/11.6 Additionally, “essential” cannot be conflated with “emergent,” as can easily occur in extreme circumstances. Early and sustained efforts are required to ensure that patients with SMI who may be teetering on the edge of emergency status do not slip off that edge, especially when the emergency medical system is operating over capacity.

A comprehensive outbreak response must consider that a pandemic is not only a medical crisis but a mental health crisis and a communication emergency.7 Mental health clinicians need to provide accurate information and help patients cope with their fears.

Continue to: Psychological aspects of pandemics

Psychological aspects of pandemics. Previous infectious outbreaks have reaffirmed that mental health plays an outsized role during epidemics. Chaos, uncertainty, fear of death, and loss of income and housing cause prolonged stress and exact a psychological toll.

Adverse psychological impacts include expectable, normal reactions such as stress-induced anxiety or insomnia. In addition, new-onset psychiatric illnesses or exacerbations of existing ones may emerge.8 As disillusionment and demoralization appear in the wake of the acute phase, with persistently high unemployment, suicide prevention becomes an important goal.9

Pandemics lead to expectable behavioral responses (eg, increases in substance use and interpersonal conflict). Fear-based decisions may result in unhelpful behavior, such as hoarding medications (which may result in shortages) or dangerous, unsupervised use of unproven medications (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Trust is needed to accept public-health measures, and recommendations (eg, wearing masks) must be culturally informed to be credible and effective.

Because people are affected differently, at individual, cultural, and socioeconomic levels, they will view the situation differently. For many people, secondary stressors (eg, job loss) may be more disastrous than the primary medical event (ie, the pandemic). This distinction is critical because concrete financial help, not psychiatric care, is needed. Sometimes, even when a psychiatric disorder such as SMI or major neurocognitive disorder is present, the illusion of an acute decompensation can be created by the loss of social and structural supports that previously scaffolded a person’s life.

Mental illness prevention. Community mental-health surveillance is important to monitor for distress, psychiatric symptoms, health-risk behaviors, risk and safety perception, and preparedness. Clinicians must be ready to normalize expectable and temporary distress, while recognizing when that distress becomes pathological. This may be difficult in patients with SMI who often already have reduced stress tolerance or problem-based coping skills.10

Continue to: Psychological first aid...

Psychological first aid (PFA) is a standard intervention recommended by the World Health Organization for most individuals following a disaster; it is evidence-informed and has face validity.11 Intended to relieve distress by creating an environment that is safe, calm, and connected, PFA fosters self-efficacy and hope. While PFA is a form of universal prevention, it is not designed for patients with SMI, is not a psychiatric intervention, and is not provided by clinicians. Its principles, however, can easily be applied to patients with SMI to prevent distressing symptoms from becoming a relapse.

Communication. Good risk and crisis communication are critical because individual and population behavior will be governed by the perception of risk and fear, and not by facts. Failure to manage the “infodemic”7—with its misinformation, contradictory messages, and rumors—jeopardizes infection control if patients become paralyzed by uncertainty and fear. Scapegoating occurs easily during times of threat, and society must contain the parallel epidemic of xenophobia based on stigma and misinformation.12

Decision-making under uncertainty is not perfect and subject to revision as better information becomes available. Pointing this out to the public is delicate but essential to curtail skepticism and mistrust when policies are adjusted in response to new circumstances and knowledge.

Mistrust of an authority’s legitimacy and fear-based decisions lead to lack of cooperation with public-health measures, which can undermine an effective response to the pandemic. Travel restrictions or quarantine measures will not be followed if individuals question their importance. Like the general public, patients need education and clear communication to address their fear of contagion, dangers posed to family (and pets), and mistrust of authority and government. A lack of appreciation of the seriousness of the pandemic and individual responsibility may need to be addressed. Two important measures to accomplish this are steering patients to reputable sources of information and advising that they limit media exposure.

Resilience-building. Community and workplace resilience are important aspects of making it through a disaster as best as possible. Resilience is not innate and fixed; it must be deliberately built.13 Choosing an attitude of post-traumatic growth over the victim narrative is a helpful stance. Practicing self-care (rest, nutrition, exercise) and self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness) is good advice for patients and caregivers alike.

Continue to: Workforce protection

Workforce protection. Compared to other disasters, infectious outbreaks disproportionally affect the medical community, and care delivery is at stake. While psychological and psychiatric needs may increase during a pandemic, services often contract, day programs and clinics close, teams are reduced to skeleton crews, and only emergency psychiatric care is available. Workforce protection is critical to avoid illness or simple absenteeism due to mistrust of protective measures.

Only a well-briefed, well-led, well-supported, and adequately resourced workforce is going to be effective in managing this public-health emergency. Burnout and moral injury are feared long-term consequences for health care workers that need to be proactively addressed.14 As opposed to other forms of disasters, managing your own fears about safety is important. Clinicians and their patients sit in the proverbial same boat.

Ethics. The anticipated need to ration life-saving care (eg, ventilators) has been at the forefront of ethical concerns.15 In psychiatry, the question of involuntary public-health interventions for uncooperative psychiatric patients sits uncomfortably between public-health ethics and human rights, and is an opportunity for collaboration with public-health and infectious-disease colleagues.

Redeployed clinicians and those working under substandard conditions may be concerned about civil liability due to a modified standard of care during a crisis. Some clinicians may ask if their duty to care must override their natural instinct to protect themselves. There is a lot of room for resentment in these circumstances. Redeployed or otherwise “conscripted” clinicians may resent administrators, especially those administering from the safety of their homes. Those “left behind” to work in potentially precarious circumstances may resent their absent colleagues. Moreover, these front-line clinicians may have been forced to make ethical decisions for which they were not prepared.16 Maintaining morale is far from trivial, not just during the pandemic, but afterward, when (and if) the entire workforce is reunited. All parties need to be mindful of how their actions and decisions impact and are perceived by others, both in the hospital and at home.

Managing patients with SMI during COVID-19

Patients with SMI are potentially hard hit by COVID-19 due to a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment: SARS-CoV-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting patients with SMI who are vulnerable hosts in permissive environments (Figure).

Continue to: While not as infectious as measles...

While not as infectious as measles, COVID-19 is more infectious than the seasonal flu virus.17 It can lead to uncontrolled infection within a short period of time, particularly in enclosed settings. Outbreaks have occurred readily on cruise ships and aircraft carriers as well as in nursing homes, homeless shelters, prisons, and group homes.

Patients with SMI are vulnerable hosts because they have many of the medical risk factors18 that portend a poor prognosis if they become infected, including pre-existing lung conditions and heart disease19 as well as diabetes and obesity.20 Obesity likely creates a hyperinflammatory state and a decrease in vital capacity. Patient-related behavioral factors include poor early-symptom reporting and ineffective infection control.

Unfavorable social determinants of health include not only poverty but crowded housing that is a perfect incubator for COVID-19.

Priority treatment goals. The overarching goal during a pandemic is to keep patients with SMI in psychiatric treatment and prevent them from disengaging from care in the service of infection control. Urgent tasks include infection control, relapse prevention, and preventing treatment disengagement and loneliness.

Infection control. As trusted sources of information, psychiatrists can play an important role in infection control in several important ways:

- educating patients about infection-control measures and public-health recommendations

- helping patients understand what testing can accomplish and when to pursue it

- encouraging protective health behaviors (eg, hand washing, mask wearing, physical distancing)

- assessing patients’ risk appreciation

- assessing for and addressing obstacles to implementing and complying with infection-control measures

- explaining contact tracing

- providing reassurance.

Continue to: Materials and explanations...

Materials and explanations must be adapted for patient understanding.

Patients with disorganization or cognitive disturbances may have difficulties cooperating or problem-solving. Patients with negative symptoms may be inappropriately unconcerned and also inaccurately report symptoms that suggest COVID-19. Acute psychosis or mania can prevent patients from complying with public-health efforts. Some measures may be difficult to implement if the means are simply not there (eg, physical distancing in a crowded apartment). Previously open settings (eg, group homes) have had to develop new mechanisms under the primacy of infection control. Inpatient units—traditionally places where community, shared healing, and group therapy are prized—have had to decrease maximum occupancy, limit the number of patients attending groups, and discourage or outrightly prohibit social interaction (eg, dining together).

Relapse prevention. Patients who take maintenance medications need to be supported. A manic or psychotic relapse during a pandemic puts patients at risk of acquiring and spreading COVID-19. “Treatment as prevention” is a slogan from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care that captures the importance of antiretroviral treatment to prevent medical complications from HIV, and also to reduce infecting other people. By analogy, psychiatric treatment for patients with SMI can prevent psychiatric instability and thereby control viral transmission. Avoiding sending psychiatric patients to a potentially stressed acute-care system is important.

Psychosocial support. Clinics need to ensure that patients continue to engage in care beyond medication-taking to proactively prevent psychiatric exacerbations. Healthful, resilience-building behaviors should be encouraged while monitoring and counseling against maladaptive ones (eg, increased substance use). Supporting patients emotionally and helping them solve problems are critical, particularly for those who are subjected to quarantine or isolation. Obviously, in these latter situations, outreach will be necessary and may require creative delivery systems and dedicated clinicians for patients who lack access to the technology necessary for virtual visits. Havens and Ghaemi21 have suggested that a good therapeutic alliance can be viewed as a mood stabilizer. Helping patients grieve losses (loved ones, jobs, sense of safety) may be an important part of support.

Even before COVID-19, loneliness was a major factor for patients with schizophrenia.22 A psychiatric clinic is one aspect of a person with SMI’s social network; during the initial phase of the pandemic, many clinics and treatment programs closed. Patients for whom clinics structure and anchor their activities are at high risk of disconnecting from treatment, staying at home, and becoming lonely.

Continue to: Caregivers are always important...

Caregivers are always important to SMI patients, but they may assume an even bigger role during this pandemic. Some patients may have moved in with a relative, after years of living on their own. In other cases, stable caregiver relationships may be disrupted due to COVID-19–related sickness in the caregiver; if not addressed, this can result in a patient’s clinical decompensation. Clinicians should take the opportunity to understand who a patient’s caregivers are (group home staff, families) and rekindle clinical contact with them. Relationships with caregivers that may have been on “autopilot” during normal times are opportunities for welcome support and guidance, to the benefit of both patients and caregivers.

Table 1 summarizes clinical tasks that need to be kept in mind when conducting clinic visits during COVID-19 in order to achieve the high-priority treatment goals of infection control, relapse prevention, and psychosocial support.

Differential diagnosis. Neuropsychiatric syndromes have long been observed in influenza pandemics,23 due both to direct viral effects and to the effects of critical illness on the brain. Two core symptoms of COVID-19—anosmia and ageusia—suggest that COVID-19 can directly affect the brain. While neurologic manifestations are common,24 it remains unclear to what extent COVID-19 can directly “cause” psychiatric symptoms, or if such symptoms are the result of cytokines25 or other medical processes (eg, thromboembolism).26 Psychosis due to COVID-19 may, in some cases, represent a stress-related brief psychotic disorder.27

Hospitalized patients who have recovered from COVID-19 may have experienced prolonged sedation and severe delirium in an ICU.28 Complications such as posttraumatic stress disorder,29 hypoperfusion-related brain injuries, or other long-term cognitive difficulties may result. In previous flu epidemics, patients developed serious neurologic complications such as post-encephalitic Parkinson’s disease.30

Any person subjected to isolation or quarantine is at risk for psychiatric complications.31 Patients with SMI who live in group homes may be particularly susceptible to new rules, including no-visitor policies.

Continue to: Outpatients whose primary disorder...

Outpatients whose primary disorder is well controlled may, like anyone else, struggle with the effects of the pandemic. It is necessary to carefully differentiate non-specific symptoms associated with stress from the emergence of a new disorder resulting from stress.32 For some patients, grief or adjustment disorders should be considered. Prolonged stress and uncertainty may eventually lead to an exacerbation of a primary disorder, particularly if the situation (eg, financial loss) does not improve or worsens. Demoralization and suicidal thinking need to be monitored. Relapse or increased use of alcohol or other substances as a response to stress may also complicate the clinical picture.33 Last, smoking cessation as a major treatment goal in general should be re-emphasized and not ignored during the ongoing pandemic.34

Table 2 summarizes psychiatric symptoms that need to be considered when managing a patient with SMI during this pandemic.

Treatment tools

Psychopharmacology. Even though crisis-mode prescribing may be necessary, the safe use of psychotropics remains the goal of psychiatric prescribing. Access to medications becomes a larger consideration; for many patients, a 90-day supply may be indicated. Review of polypharmacy, including for pneumonia risk, should be undertaken. Preventing drooling (eg, from sedation, clozapine, extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) will decrease aspiration risk.

In general, treatment of psychiatric symptoms in a patient with COVID-19 follows usual guidelines. The best treatment for COVID-19 patients with delirium, however, remains to be established, particularly how to manage severe agitation.28 Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions between psychotropics and antiviral treatments for COVID-19 (eg, QTc prolongation) can be expected and need to be reviewed.35 For stress-related anxiety, judicious pharmacotherapy can be helpful. Diazepam given at the earliest signs of a psychotic relapse may stave off a relapse for patients with schizophrenia.36 Even if permitted under relaxed prescribing rules during a public-health emergency, prescribing controlled substances without seeing patients in person requires additional thought. In some cases, adjusting the primary medication to buffer against stress may be preferred (eg, adjusting an antipsychotic in a patient on maintenance treatment for schizophrenia, particularly if a low-dose strategy is pursued).

Clozapine requires registry-based prescribing and bloodwork (“no blood, no drug”). The use of clozapine during this public-health emergency has been made easier because of FDA guidance that allows clozapine to be dispensed without blood work if obtaining blood work is not possible (eg, a patient is quarantined) or can be accomplished only at substantial risk to patients and the population at large. Under certain conditions, clozapine can be dispensed safely and in a way that is consistent with infection prevention. Clozapine-treated patients admitted with COVID-19 should be monitored for clozapine toxicity and the clozapine dose adjusted.37 A consensus statement consistent with the FDA and clinical considerations for using clozapine during COVID-19 is summarized in Table 3.38

Continue to: Long-acting injectable antipsychotics...

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) pose a problem because they require in-person visits. Ideally, during a pandemic, patients should be seen in person as frequently as medically necessary but as infrequently as possible to limit exposure of both patients and staff. Table 4 provides some clinical recommendations on how to use LAIs during the pandemic.39

Supportive psychotherapy may be the most important tool we have in helping patients with loss and uncertainty during these challenging months.40 Simply staying in contact with patients plays a major role in preventing care discontinuity. Even routine interactions have become stressful, with everyone wearing a mask that partially obscures the face. People with impaired hearing may find it even more difficult to understand you.

Education, problem-solving, and a directive, encouraging style are major tools of supportive psychotherapy to reduce symptoms and increase adaptive skills. Clarify that social distancing refers to physical, not emotional, distancing. The judicious and temporary use of anxiolytics is appropriate to reduce anxiety. Concrete help and problem-solving (eg, filling out forms) are examples of proactive crisis intervention.

Telepsychiatry emerged in the pandemic’s early days as the default mode of practice in order to limit in-person contacts.41 Like all new technology, telepsychiatry brings progress and peril.42 While it has gone surprisingly well for most, the “digital divide” does not afford all patients access to the needed technology. The long-term effectiveness and acceptance of telehealth remain to be seen. (Editor’s Note: For more about this topic, see “Telepsychiatry: What you need to know.”

Lessons learned and outlook

Infectious outbreaks have historically inflicted long-term disruptions on societies and altered the course of history. However, each disaster is unique, and lessons from previous disasters may only partially apply.43 We do not yet know how this one will end, including how long it will take for the world’s economies to recover. If nothing else, the current public-health emergency has brought to the forefront what psychiatrists have always known: health disparities are partially responsible for different disease risks (in this case, the risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2).5 It may not be a coincidence that the Black Lives Matter movement is becoming a major impetus for social change at a time when the pandemic is exposing health-care inequalities.

Continue to: Some areas of the country...

Some areas of the country succeeded in reducing infections and limiting community spread, which ushered in an uneasy sense of normalcy even while the pandemic continues. At least for now, these locales can focus on rebuilding and preparing for expectable fluctuations in disease activity, including the arrival of the annual flu season on top of COVID-19.44 Recovery is not a return to the status quo ante but building stronger communities—“building back better.”45 Unless there is a continuum of care, shortcomings in one sector will have ripple effects through the entire system, particularly for psychiatric care for patients with SMI, which was inadequate before the pandemic.

Ensuring access to critical care was a priority during the pandemic’s early phase but came at the price of deferring other types of care, such as routine primary care; the coming months will see the downstream consequences of this approach,46 including for patients with SMI.

In the meantime, doing our job as clinicians, as Camus’s fictitious Dr. Bernard Rieux from the epigraph responds when asked how to define decency, may be the best we can do in these times. This includes contributing to and molding our field’s future and fostering a sense of agency in our patients and in ourselves. Major goals will be to preserve lessons learned, maintain flexibility, and avoid a return to unhelpful overregulation and payment models that do not reflect the flexible, person-centered care so important for patients with SMI.47

Bottom Line

During a pandemic, patients with serious mental illness may be easily forgotten as other issues overshadow the needs of this impoverished group. During a pandemic, the priority treatment goals for these patients are infection control, relapse prevention, and preventing treatment disengagement and loneliness. A pandemic requires changes in how patients with serious mental illness will receive psychopharmacology and psychotherapy.

Related Resources

- Huremović D (ed). Psychiatry of pandemics: a mental health response to infection outbreak. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2019.

- Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Weisaeth L, et al (eds). Textbook of disaster psychiatry. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. Coronavirus resources. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus.

- SMI Adviser. Make informed decisions related to COVID-19 and mental health. https://smiadviser.org/about/covid.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Diazepam • Valium

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

“This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s about decency. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency . ”

– Albert Camus, La Peste (1947)1

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1 swine flu, Ebola, Zika, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): the 21st century has already been witness to several serious infectious outbreaks and pandemics,2 but none has been as deadly and consequential as the current one. The ongoing SARS-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is shaping not only current psychiatric care but the future of psychiatry. Now that we are beyond the initial stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when psychiatrists had a crash course in disaster psychiatry, our attention must shift to rebuilding and managing disillusionment and other psychological fallout of the intense early days.3

In this article, we offer guidance to psychiatrists caring for patients with serious mental illness (SMI) during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Patients with SMI are easily forgotten as other issues (eg, preserving ICU capacity) overshadow the already historically neglected needs of this impoverished group.4 From both human and public-health perspectives, this inattention is a mistake. Assuring psychiatric stability is critically important to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in marginalized communities comprised of individuals who are poor, members of racial minorities, and others who already experience health disparities.5 Without controlling transmission in these groups, the pandemic will not be sufficiently contained.

We begin by highlighting general principles of pandemic management because caring for patients with SMI does not occur in a vacuum. Infectious outbreaks require not only helping those who need direct medical care because they are infected, but also managing populations that are at risk of getting infected, including health care and other essential workers.

Principles of pandemic management

Delivery of medical care during a pandemic differs from routine care. An effective disaster response requires collaboration and coordination among public-health, treatment, and emergency systems. Many institutions shift to an incident management system and crisis leadership, with clear lines of authority to coordinate responders and build medical surge capacity. Such a top-down leadership approach must plan and allow for the emergence of other credible leaders and for the restoration of people’s agency.

Unfortunately, adaptive capacity may be limited, especially in the public sector and psychiatric care system, where resources are already poor. Particularly early in a pandemic, services considered non-essential—which includes most psychiatric outpatient care—can become unavailable. A major effort is needed to prevent the psychiatric care system from contracting further, as happened during 9/11.6 Additionally, “essential” cannot be conflated with “emergent,” as can easily occur in extreme circumstances. Early and sustained efforts are required to ensure that patients with SMI who may be teetering on the edge of emergency status do not slip off that edge, especially when the emergency medical system is operating over capacity.

A comprehensive outbreak response must consider that a pandemic is not only a medical crisis but a mental health crisis and a communication emergency.7 Mental health clinicians need to provide accurate information and help patients cope with their fears.

Continue to: Psychological aspects of pandemics

Psychological aspects of pandemics. Previous infectious outbreaks have reaffirmed that mental health plays an outsized role during epidemics. Chaos, uncertainty, fear of death, and loss of income and housing cause prolonged stress and exact a psychological toll.

Adverse psychological impacts include expectable, normal reactions such as stress-induced anxiety or insomnia. In addition, new-onset psychiatric illnesses or exacerbations of existing ones may emerge.8 As disillusionment and demoralization appear in the wake of the acute phase, with persistently high unemployment, suicide prevention becomes an important goal.9

Pandemics lead to expectable behavioral responses (eg, increases in substance use and interpersonal conflict). Fear-based decisions may result in unhelpful behavior, such as hoarding medications (which may result in shortages) or dangerous, unsupervised use of unproven medications (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Trust is needed to accept public-health measures, and recommendations (eg, wearing masks) must be culturally informed to be credible and effective.

Because people are affected differently, at individual, cultural, and socioeconomic levels, they will view the situation differently. For many people, secondary stressors (eg, job loss) may be more disastrous than the primary medical event (ie, the pandemic). This distinction is critical because concrete financial help, not psychiatric care, is needed. Sometimes, even when a psychiatric disorder such as SMI or major neurocognitive disorder is present, the illusion of an acute decompensation can be created by the loss of social and structural supports that previously scaffolded a person’s life.

Mental illness prevention. Community mental-health surveillance is important to monitor for distress, psychiatric symptoms, health-risk behaviors, risk and safety perception, and preparedness. Clinicians must be ready to normalize expectable and temporary distress, while recognizing when that distress becomes pathological. This may be difficult in patients with SMI who often already have reduced stress tolerance or problem-based coping skills.10

Continue to: Psychological first aid...

Psychological first aid (PFA) is a standard intervention recommended by the World Health Organization for most individuals following a disaster; it is evidence-informed and has face validity.11 Intended to relieve distress by creating an environment that is safe, calm, and connected, PFA fosters self-efficacy and hope. While PFA is a form of universal prevention, it is not designed for patients with SMI, is not a psychiatric intervention, and is not provided by clinicians. Its principles, however, can easily be applied to patients with SMI to prevent distressing symptoms from becoming a relapse.

Communication. Good risk and crisis communication are critical because individual and population behavior will be governed by the perception of risk and fear, and not by facts. Failure to manage the “infodemic”7—with its misinformation, contradictory messages, and rumors—jeopardizes infection control if patients become paralyzed by uncertainty and fear. Scapegoating occurs easily during times of threat, and society must contain the parallel epidemic of xenophobia based on stigma and misinformation.12

Decision-making under uncertainty is not perfect and subject to revision as better information becomes available. Pointing this out to the public is delicate but essential to curtail skepticism and mistrust when policies are adjusted in response to new circumstances and knowledge.

Mistrust of an authority’s legitimacy and fear-based decisions lead to lack of cooperation with public-health measures, which can undermine an effective response to the pandemic. Travel restrictions or quarantine measures will not be followed if individuals question their importance. Like the general public, patients need education and clear communication to address their fear of contagion, dangers posed to family (and pets), and mistrust of authority and government. A lack of appreciation of the seriousness of the pandemic and individual responsibility may need to be addressed. Two important measures to accomplish this are steering patients to reputable sources of information and advising that they limit media exposure.

Resilience-building. Community and workplace resilience are important aspects of making it through a disaster as best as possible. Resilience is not innate and fixed; it must be deliberately built.13 Choosing an attitude of post-traumatic growth over the victim narrative is a helpful stance. Practicing self-care (rest, nutrition, exercise) and self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness) is good advice for patients and caregivers alike.

Continue to: Workforce protection

Workforce protection. Compared to other disasters, infectious outbreaks disproportionally affect the medical community, and care delivery is at stake. While psychological and psychiatric needs may increase during a pandemic, services often contract, day programs and clinics close, teams are reduced to skeleton crews, and only emergency psychiatric care is available. Workforce protection is critical to avoid illness or simple absenteeism due to mistrust of protective measures.

Only a well-briefed, well-led, well-supported, and adequately resourced workforce is going to be effective in managing this public-health emergency. Burnout and moral injury are feared long-term consequences for health care workers that need to be proactively addressed.14 As opposed to other forms of disasters, managing your own fears about safety is important. Clinicians and their patients sit in the proverbial same boat.

Ethics. The anticipated need to ration life-saving care (eg, ventilators) has been at the forefront of ethical concerns.15 In psychiatry, the question of involuntary public-health interventions for uncooperative psychiatric patients sits uncomfortably between public-health ethics and human rights, and is an opportunity for collaboration with public-health and infectious-disease colleagues.

Redeployed clinicians and those working under substandard conditions may be concerned about civil liability due to a modified standard of care during a crisis. Some clinicians may ask if their duty to care must override their natural instinct to protect themselves. There is a lot of room for resentment in these circumstances. Redeployed or otherwise “conscripted” clinicians may resent administrators, especially those administering from the safety of their homes. Those “left behind” to work in potentially precarious circumstances may resent their absent colleagues. Moreover, these front-line clinicians may have been forced to make ethical decisions for which they were not prepared.16 Maintaining morale is far from trivial, not just during the pandemic, but afterward, when (and if) the entire workforce is reunited. All parties need to be mindful of how their actions and decisions impact and are perceived by others, both in the hospital and at home.

Managing patients with SMI during COVID-19

Patients with SMI are potentially hard hit by COVID-19 due to a “tragic” epidemiologic triad of agent-host-environment: SARS-CoV-2 is a highly infectious agent affecting patients with SMI who are vulnerable hosts in permissive environments (Figure).

Continue to: While not as infectious as measles...

While not as infectious as measles, COVID-19 is more infectious than the seasonal flu virus.17 It can lead to uncontrolled infection within a short period of time, particularly in enclosed settings. Outbreaks have occurred readily on cruise ships and aircraft carriers as well as in nursing homes, homeless shelters, prisons, and group homes.

Patients with SMI are vulnerable hosts because they have many of the medical risk factors18 that portend a poor prognosis if they become infected, including pre-existing lung conditions and heart disease19 as well as diabetes and obesity.20 Obesity likely creates a hyperinflammatory state and a decrease in vital capacity. Patient-related behavioral factors include poor early-symptom reporting and ineffective infection control.

Unfavorable social determinants of health include not only poverty but crowded housing that is a perfect incubator for COVID-19.

Priority treatment goals. The overarching goal during a pandemic is to keep patients with SMI in psychiatric treatment and prevent them from disengaging from care in the service of infection control. Urgent tasks include infection control, relapse prevention, and preventing treatment disengagement and loneliness.

Infection control. As trusted sources of information, psychiatrists can play an important role in infection control in several important ways:

- educating patients about infection-control measures and public-health recommendations

- helping patients understand what testing can accomplish and when to pursue it

- encouraging protective health behaviors (eg, hand washing, mask wearing, physical distancing)

- assessing patients’ risk appreciation

- assessing for and addressing obstacles to implementing and complying with infection-control measures

- explaining contact tracing

- providing reassurance.

Continue to: Materials and explanations...

Materials and explanations must be adapted for patient understanding.

Patients with disorganization or cognitive disturbances may have difficulties cooperating or problem-solving. Patients with negative symptoms may be inappropriately unconcerned and also inaccurately report symptoms that suggest COVID-19. Acute psychosis or mania can prevent patients from complying with public-health efforts. Some measures may be difficult to implement if the means are simply not there (eg, physical distancing in a crowded apartment). Previously open settings (eg, group homes) have had to develop new mechanisms under the primacy of infection control. Inpatient units—traditionally places where community, shared healing, and group therapy are prized—have had to decrease maximum occupancy, limit the number of patients attending groups, and discourage or outrightly prohibit social interaction (eg, dining together).

Relapse prevention. Patients who take maintenance medications need to be supported. A manic or psychotic relapse during a pandemic puts patients at risk of acquiring and spreading COVID-19. “Treatment as prevention” is a slogan from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care that captures the importance of antiretroviral treatment to prevent medical complications from HIV, and also to reduce infecting other people. By analogy, psychiatric treatment for patients with SMI can prevent psychiatric instability and thereby control viral transmission. Avoiding sending psychiatric patients to a potentially stressed acute-care system is important.

Psychosocial support. Clinics need to ensure that patients continue to engage in care beyond medication-taking to proactively prevent psychiatric exacerbations. Healthful, resilience-building behaviors should be encouraged while monitoring and counseling against maladaptive ones (eg, increased substance use). Supporting patients emotionally and helping them solve problems are critical, particularly for those who are subjected to quarantine or isolation. Obviously, in these latter situations, outreach will be necessary and may require creative delivery systems and dedicated clinicians for patients who lack access to the technology necessary for virtual visits. Havens and Ghaemi21 have suggested that a good therapeutic alliance can be viewed as a mood stabilizer. Helping patients grieve losses (loved ones, jobs, sense of safety) may be an important part of support.

Even before COVID-19, loneliness was a major factor for patients with schizophrenia.22 A psychiatric clinic is one aspect of a person with SMI’s social network; during the initial phase of the pandemic, many clinics and treatment programs closed. Patients for whom clinics structure and anchor their activities are at high risk of disconnecting from treatment, staying at home, and becoming lonely.

Continue to: Caregivers are always important...

Caregivers are always important to SMI patients, but they may assume an even bigger role during this pandemic. Some patients may have moved in with a relative, after years of living on their own. In other cases, stable caregiver relationships may be disrupted due to COVID-19–related sickness in the caregiver; if not addressed, this can result in a patient’s clinical decompensation. Clinicians should take the opportunity to understand who a patient’s caregivers are (group home staff, families) and rekindle clinical contact with them. Relationships with caregivers that may have been on “autopilot” during normal times are opportunities for welcome support and guidance, to the benefit of both patients and caregivers.

Table 1 summarizes clinical tasks that need to be kept in mind when conducting clinic visits during COVID-19 in order to achieve the high-priority treatment goals of infection control, relapse prevention, and psychosocial support.

Differential diagnosis. Neuropsychiatric syndromes have long been observed in influenza pandemics,23 due both to direct viral effects and to the effects of critical illness on the brain. Two core symptoms of COVID-19—anosmia and ageusia—suggest that COVID-19 can directly affect the brain. While neurologic manifestations are common,24 it remains unclear to what extent COVID-19 can directly “cause” psychiatric symptoms, or if such symptoms are the result of cytokines25 or other medical processes (eg, thromboembolism).26 Psychosis due to COVID-19 may, in some cases, represent a stress-related brief psychotic disorder.27

Hospitalized patients who have recovered from COVID-19 may have experienced prolonged sedation and severe delirium in an ICU.28 Complications such as posttraumatic stress disorder,29 hypoperfusion-related brain injuries, or other long-term cognitive difficulties may result. In previous flu epidemics, patients developed serious neurologic complications such as post-encephalitic Parkinson’s disease.30

Any person subjected to isolation or quarantine is at risk for psychiatric complications.31 Patients with SMI who live in group homes may be particularly susceptible to new rules, including no-visitor policies.

Continue to: Outpatients whose primary disorder...