User login

Story

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

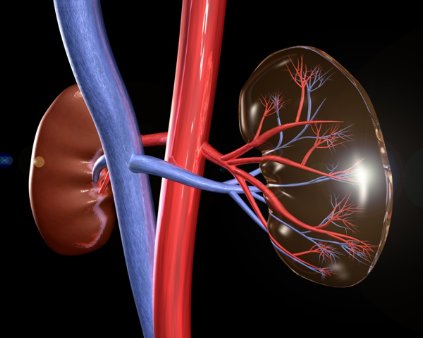

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.