User login

A deadly chain reaction, on one condition

Story

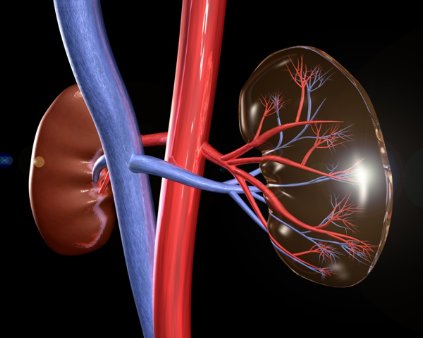

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

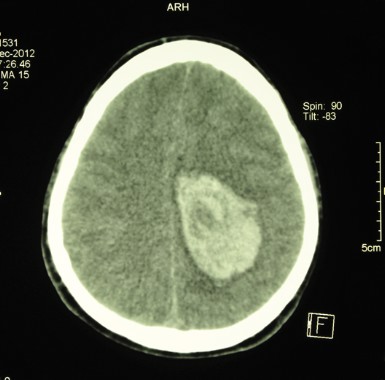

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

DM was a 60-year-old woman with a history of granulomatosis polyangiitis controlled with cyclophosphamide. She was sent to the hospital as a direct admission by her nephrologist because of worsening renal function and the possibility that DM was suffering from uncontrolled vasculitis. DM was admitted to the hospital by Dr. Hospitalist 1. The history and physical documented that DM was generally weak, but otherwise without specific complaints.

The serum creatinine was 3.89 mg/dL, and coagulation studies were normal. DM’s comorbidities were numerous, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The referring nephrologist had already written orders for a pulsed steroid protocol (Solu-Medrol intravenously for 3 days), in addition to arranging for a renal biopsy by interventional radiology (IR) the following day.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 wrote standard admission orders and made DM nothing per os after midnight. For venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, Dr. Hospitalist 1 also wrote for DM to receive mechanical compression to her legs and to begin Lovenox 30 mg subcutaneously daily after the biopsy, only when OK with IR.

The next day, DM was seen in the morning by her nephrologist and Dr. Hospitalist 2 on rounds. Later that afternoon, DM underwent a right renal biopsy under CT guidance by IR. A small hematoma was noted immediately following the procedure. At 8 p.m. that night, DM received 30 mg of Lovenox subcutaneously.

Overnight, DM became tachycardic and complained of right flank pain. Her morning labs drawn at 5 a.m. found a significant drop in her blood count (Hgb, 6.1 mg/dL) and decline in her renal function (serum creatinine, 4.46 mg/dL). A repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis found an enlarging perinephric hematoma. Dr. Hospitalist 2 immediately moved DM to the ICU and began supportive transfusions.

DM’s blood counts and renal function stabilized over the next 24-36 hrs. However, on the evening of hospital day 4 (ICU day 2), DM experienced shortness of breath followed quickly by a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Telemetry strips before the code demonstrated ST-elevation myocardial infarction. It took almost 45minutes of resuscitation, but DM regained her pulse. At this point, she was now intubated and critically ill. Cardiology was consulted, but given DM’s recent perinephric hematoma, it was felt that she would not tolerate antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies. Subsequent echocardiogram demonstrated a severely damaged left ventricle from her MI. Even worse, DM went into acute renal failure and shock liver with coagulopathy.

After multiple discussions with the family in the ensuing week, care was ultimately withdrawn and DM passed away.

Complaint

The family understood the bleeding risk of a renal biopsy, but they were upset to learn that DM received blood thinners around the time of her procedure. DM had a previous bleed on Coumadin years earlier, and she even had a "Coumadin allergy" documented in the chart. A lawsuit was filed and both the hospital (employer of the nurses) and Dr. Hospitalist 1 were named in the suit. The complaint alleged that it was substandard for DM to have received Lovenox in this case and that the Lovenox caused the hemorrhage, which in turn led to a myocardial infarction and death.

Scientific principles

Granulomatosis polyangiitis increases the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Patients at risk for thrombosis benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation. However, bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy and anticoagulation increases that risk. Postbiopsy bleeding can occur into one of three sites: 1) the collecting system (leading to microscopic or gross hematuria); 2) underneath the renal capsule (leading to pressure tamponade and pain); or 3) into the perinephric space (leading to hematoma formation and a possibly large drop in hemoglobin). Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12-24 hours of the biopsy, but bleeding may occur up to several days after the procedure. Anticoagulation should not be used for at least 12-24 hours postbiopsy, and if possible, withholding anticoagulants for a more prolonged period of up to 1 week may be preferable.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Discovery in this case confirmed that the original order by Dr. Hospitalist 1 was not transcribed into the medical administration record with any conditions, and IR was not contacted to approve the Lovenox prior to administration. The nurse who gave the Lovenox was simply following the incomplete order that existed on the administration record.

As a result, the hospital settled with the plaintiff early in the process; yet the plaintiff continued to assert that the order itself (whether it was followed properly or not) was substandard and Dr. Hospitalist 1 was also negligent. Dr. Hospitalist 1 defended her Lovenox order as being appropriate and reasonable because DM was at risk for VTE, the dose prescribed was reduced for renal impairment, and it was a conditional order that required approval by interventional radiology prior to medication administration. Dr. Hospitalist 1 was resolute that if her order had just been followed, DM would never have received the medication.

Conclusion

Hospitalists write conditional orders every day. In fact, all "PRN" orders are conditional and presume the use of nursing clinical judgment. However, some conditional orders are directed at other physicians or services (for example, "Discharge the patient if OK with surgery" or "Resume Coumadin if OK with orthopedics").

Often these orders are expedient and typically replace direct communication. But hospitalists should remember that such conditional orders trigger a potential act of commission with nursing as the communication "go-between." There was nothing unreasonable about the conditional order for Lovenox in this case per se. Yet, had this order not been written at all – the chain reaction that subsequently occurred may have been avoided altogether. The jury in this case returned a defense verdict in favor of the hospitalist.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

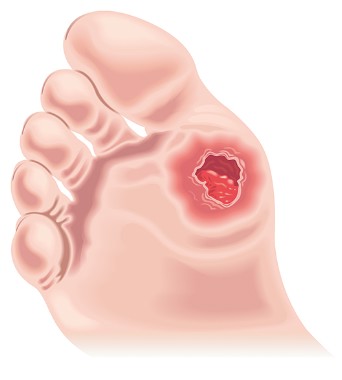

A Diabetic Foot Infection Progresses to Amputation

The Story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The Story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The Story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

An unfortunate twist

The story

FR was a 55-year-old woman who developed relatively acute and diffuse upper abdominal pain shortly after finishing dinner with friends at a local restaurant. Over the next 1-2 hours and after returning home, FR’s pain became most severe and was associated with nausea and emesis. FR contacted her daughter, who came over to assist. At approximately 10:30 p.m., FR called for an ambulance and was taken to the nearest emergency department.

On arrival at the ED, FR had a normal blood pressure and heart rate, but complained of 10/10 abdominal pain. An EKG was quickly performed and was normal. On examination, FR was noted by the ED physician as "uncooperative answering questions, rocking in bed moaning." The abdomen was documented as soft but diffusely tender to palpation in all four quadrants. A posteroanterior/lateral chest radiograph (CXR), full blood chemistries, and a complete blood cell count were obtained.

The initial impression by the ED physician was biliary colic, and he also ordered a right upper quadrant ultrasound. In the meantime, FR received a "GI cocktail" (Mylanta, viscous lidocaine, and Donnatal) by mouth, along with intravenous morphine and Zofran. About 1 hour later, FR reported minimal improvement in her symptoms. The CXR, right upper quadrant ultrasound, Chem-12, lipase, and CBC all returned within normal limits.

At this point, the ED physician recommended discharge home with outpatient follow-up. The daughter, who had been with her mother all evening, became very upset and demanded that the patient be admitted because something was obviously wrong with her mother.

The ED physician called Dr. Hospitalist to admit FR for uncontrolled abdominal pain. An hour later, Dr. Hospitalist saw FR on the medical floor, by which time the daughter had left the hospital for home.

FR was lethargic from several doses of hydromorphone, but she was still complaining of severe abdominal pain. Dr. Hospitalist documented that FR had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anxiety, and depression, along with a gastric lap-band procedure 2 years ago for morbid obesity. FR’s abdomen was noted to be "reasonably soft" with hypoactive bowel sounds. The impression from Dr. Hospitalist was acute postprandial abdominal pain of unclear etiology. The plan included a routine GI consult, a routine plain film of the abdomen to look for evidence of gastric distention, keeping FR nothing per os (NPO), and continuing intravenous fluids and analgesia.

At 8:30 a.m., FR was found unresponsive and a Code Blue was called. Resuscitation efforts confirmed a profound acidemia (pH 6.55), and FR did not survive. FR was last seen by the nurses an hour earlier and had been documented as "sleeping." An autopsy was performed and discovered small bowel necrosis consistent with a small bowel volvulus.

Complaint

The daughter was shocked and upset over the sudden death of her mother. She felt that none of the medical providers took her mother’s complaints seriously because FR had a history of "anxiety." The daughter was particularly angry over the fact that the ED physician actually wanted to discharge FR in the presence of a lethal condition. She followed up with an attorney almost immediately, who had the case reviewed and subsequently filed a lawsuit.

The complaint alleged that the ED physician and Dr. Hospitalist both failed to appropriately image FR’s abdomen with either a plain abdominal radiograph and/or CT scan of the abdomen. The complaint further alleged that had they done so, the small bowel volvulus would have been discovered and successfully treated, preventing FR’s demise.

Scientific principles

Volvulus is a special form of mechanical intestinal obstruction. It results from abnormal twisting of a loop of bowel around the axis of its own mesentery and often results in ischemia or even infarction.

When it occurs in adults, volvulus usually affects the sigmoid colon or the cecum. In contrast, small bowel volvulus is relatively rare. Plain radiography and CT of the abdomen are the most practical and useful diagnostic modalities.

All patients suspected of having complicated bowel obstruction (complete obstruction, closed-loop obstruction, bowel ischemia, necrosis, or perforation) based upon clinical and radiologic examination should be taken to the operating room for abdominal exploration. Failure to identify and treat small bowel volvulus in a timely manner can lead to catastrophic results.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense in this case focused on the rarity of this condition, along with the limited time window to successfully save FR’s life. The defense argued that while FR was in the window for diagnosis and successful treatment (i.e., 10:30 p.m. until 3 a.m.), all of FR’s vital signs were normal, and her abdominal exam was inconsistent with an acute abdomen.

The plaintiff countered that mechanical bowel obstruction (not necessarily a rare volvulus) was always in the differential diagnosis for acute and severe abdominal pain, and the failure to perform plain radiography of the abdomen was in and of itself negligent. Plaintiff experts opined that had the providers in this case performed plain radiography as the standard of care required, FR’s rare diagnosis would have been discovered, even if by "accident."

Conclusion

Dr. Hospitalist documented a desire to obtain a plain abdominal radiograph, but he ordered it routine and therefore it was never performed prior to FR’s death. Had Dr. Hospitalist obtained the film STAT, more likely than not the volvulus would have been identified well within the window to get FR a surgical consult and to the operating room for treatment.

This case is another example of what turned out to be an incomplete workup from the ED in the setting of "uncontrolled pain" (see previous column). Admission for "pain control" is a red flag for an underlying disorder that has been missed by the initial ED evaluation. In this case, the workup should have reasonably included a plain radiograph of the abdomen. This case was eventually settled on behalf of the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

The story

FR was a 55-year-old woman who developed relatively acute and diffuse upper abdominal pain shortly after finishing dinner with friends at a local restaurant. Over the next 1-2 hours and after returning home, FR’s pain became most severe and was associated with nausea and emesis. FR contacted her daughter, who came over to assist. At approximately 10:30 p.m., FR called for an ambulance and was taken to the nearest emergency department.

On arrival at the ED, FR had a normal blood pressure and heart rate, but complained of 10/10 abdominal pain. An EKG was quickly performed and was normal. On examination, FR was noted by the ED physician as "uncooperative answering questions, rocking in bed moaning." The abdomen was documented as soft but diffusely tender to palpation in all four quadrants. A posteroanterior/lateral chest radiograph (CXR), full blood chemistries, and a complete blood cell count were obtained.

The initial impression by the ED physician was biliary colic, and he also ordered a right upper quadrant ultrasound. In the meantime, FR received a "GI cocktail" (Mylanta, viscous lidocaine, and Donnatal) by mouth, along with intravenous morphine and Zofran. About 1 hour later, FR reported minimal improvement in her symptoms. The CXR, right upper quadrant ultrasound, Chem-12, lipase, and CBC all returned within normal limits.

At this point, the ED physician recommended discharge home with outpatient follow-up. The daughter, who had been with her mother all evening, became very upset and demanded that the patient be admitted because something was obviously wrong with her mother.

The ED physician called Dr. Hospitalist to admit FR for uncontrolled abdominal pain. An hour later, Dr. Hospitalist saw FR on the medical floor, by which time the daughter had left the hospital for home.

FR was lethargic from several doses of hydromorphone, but she was still complaining of severe abdominal pain. Dr. Hospitalist documented that FR had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anxiety, and depression, along with a gastric lap-band procedure 2 years ago for morbid obesity. FR’s abdomen was noted to be "reasonably soft" with hypoactive bowel sounds. The impression from Dr. Hospitalist was acute postprandial abdominal pain of unclear etiology. The plan included a routine GI consult, a routine plain film of the abdomen to look for evidence of gastric distention, keeping FR nothing per os (NPO), and continuing intravenous fluids and analgesia.

At 8:30 a.m., FR was found unresponsive and a Code Blue was called. Resuscitation efforts confirmed a profound acidemia (pH 6.55), and FR did not survive. FR was last seen by the nurses an hour earlier and had been documented as "sleeping." An autopsy was performed and discovered small bowel necrosis consistent with a small bowel volvulus.

Complaint

The daughter was shocked and upset over the sudden death of her mother. She felt that none of the medical providers took her mother’s complaints seriously because FR had a history of "anxiety." The daughter was particularly angry over the fact that the ED physician actually wanted to discharge FR in the presence of a lethal condition. She followed up with an attorney almost immediately, who had the case reviewed and subsequently filed a lawsuit.

The complaint alleged that the ED physician and Dr. Hospitalist both failed to appropriately image FR’s abdomen with either a plain abdominal radiograph and/or CT scan of the abdomen. The complaint further alleged that had they done so, the small bowel volvulus would have been discovered and successfully treated, preventing FR’s demise.

Scientific principles

Volvulus is a special form of mechanical intestinal obstruction. It results from abnormal twisting of a loop of bowel around the axis of its own mesentery and often results in ischemia or even infarction.

When it occurs in adults, volvulus usually affects the sigmoid colon or the cecum. In contrast, small bowel volvulus is relatively rare. Plain radiography and CT of the abdomen are the most practical and useful diagnostic modalities.

All patients suspected of having complicated bowel obstruction (complete obstruction, closed-loop obstruction, bowel ischemia, necrosis, or perforation) based upon clinical and radiologic examination should be taken to the operating room for abdominal exploration. Failure to identify and treat small bowel volvulus in a timely manner can lead to catastrophic results.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense in this case focused on the rarity of this condition, along with the limited time window to successfully save FR’s life. The defense argued that while FR was in the window for diagnosis and successful treatment (i.e., 10:30 p.m. until 3 a.m.), all of FR’s vital signs were normal, and her abdominal exam was inconsistent with an acute abdomen.

The plaintiff countered that mechanical bowel obstruction (not necessarily a rare volvulus) was always in the differential diagnosis for acute and severe abdominal pain, and the failure to perform plain radiography of the abdomen was in and of itself negligent. Plaintiff experts opined that had the providers in this case performed plain radiography as the standard of care required, FR’s rare diagnosis would have been discovered, even if by "accident."

Conclusion

Dr. Hospitalist documented a desire to obtain a plain abdominal radiograph, but he ordered it routine and therefore it was never performed prior to FR’s death. Had Dr. Hospitalist obtained the film STAT, more likely than not the volvulus would have been identified well within the window to get FR a surgical consult and to the operating room for treatment.

This case is another example of what turned out to be an incomplete workup from the ED in the setting of "uncontrolled pain" (see previous column). Admission for "pain control" is a red flag for an underlying disorder that has been missed by the initial ED evaluation. In this case, the workup should have reasonably included a plain radiograph of the abdomen. This case was eventually settled on behalf of the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

The story

FR was a 55-year-old woman who developed relatively acute and diffuse upper abdominal pain shortly after finishing dinner with friends at a local restaurant. Over the next 1-2 hours and after returning home, FR’s pain became most severe and was associated with nausea and emesis. FR contacted her daughter, who came over to assist. At approximately 10:30 p.m., FR called for an ambulance and was taken to the nearest emergency department.

On arrival at the ED, FR had a normal blood pressure and heart rate, but complained of 10/10 abdominal pain. An EKG was quickly performed and was normal. On examination, FR was noted by the ED physician as "uncooperative answering questions, rocking in bed moaning." The abdomen was documented as soft but diffusely tender to palpation in all four quadrants. A posteroanterior/lateral chest radiograph (CXR), full blood chemistries, and a complete blood cell count were obtained.

The initial impression by the ED physician was biliary colic, and he also ordered a right upper quadrant ultrasound. In the meantime, FR received a "GI cocktail" (Mylanta, viscous lidocaine, and Donnatal) by mouth, along with intravenous morphine and Zofran. About 1 hour later, FR reported minimal improvement in her symptoms. The CXR, right upper quadrant ultrasound, Chem-12, lipase, and CBC all returned within normal limits.

At this point, the ED physician recommended discharge home with outpatient follow-up. The daughter, who had been with her mother all evening, became very upset and demanded that the patient be admitted because something was obviously wrong with her mother.

The ED physician called Dr. Hospitalist to admit FR for uncontrolled abdominal pain. An hour later, Dr. Hospitalist saw FR on the medical floor, by which time the daughter had left the hospital for home.

FR was lethargic from several doses of hydromorphone, but she was still complaining of severe abdominal pain. Dr. Hospitalist documented that FR had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anxiety, and depression, along with a gastric lap-band procedure 2 years ago for morbid obesity. FR’s abdomen was noted to be "reasonably soft" with hypoactive bowel sounds. The impression from Dr. Hospitalist was acute postprandial abdominal pain of unclear etiology. The plan included a routine GI consult, a routine plain film of the abdomen to look for evidence of gastric distention, keeping FR nothing per os (NPO), and continuing intravenous fluids and analgesia.

At 8:30 a.m., FR was found unresponsive and a Code Blue was called. Resuscitation efforts confirmed a profound acidemia (pH 6.55), and FR did not survive. FR was last seen by the nurses an hour earlier and had been documented as "sleeping." An autopsy was performed and discovered small bowel necrosis consistent with a small bowel volvulus.

Complaint

The daughter was shocked and upset over the sudden death of her mother. She felt that none of the medical providers took her mother’s complaints seriously because FR had a history of "anxiety." The daughter was particularly angry over the fact that the ED physician actually wanted to discharge FR in the presence of a lethal condition. She followed up with an attorney almost immediately, who had the case reviewed and subsequently filed a lawsuit.

The complaint alleged that the ED physician and Dr. Hospitalist both failed to appropriately image FR’s abdomen with either a plain abdominal radiograph and/or CT scan of the abdomen. The complaint further alleged that had they done so, the small bowel volvulus would have been discovered and successfully treated, preventing FR’s demise.

Scientific principles

Volvulus is a special form of mechanical intestinal obstruction. It results from abnormal twisting of a loop of bowel around the axis of its own mesentery and often results in ischemia or even infarction.

When it occurs in adults, volvulus usually affects the sigmoid colon or the cecum. In contrast, small bowel volvulus is relatively rare. Plain radiography and CT of the abdomen are the most practical and useful diagnostic modalities.

All patients suspected of having complicated bowel obstruction (complete obstruction, closed-loop obstruction, bowel ischemia, necrosis, or perforation) based upon clinical and radiologic examination should be taken to the operating room for abdominal exploration. Failure to identify and treat small bowel volvulus in a timely manner can lead to catastrophic results.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense in this case focused on the rarity of this condition, along with the limited time window to successfully save FR’s life. The defense argued that while FR was in the window for diagnosis and successful treatment (i.e., 10:30 p.m. until 3 a.m.), all of FR’s vital signs were normal, and her abdominal exam was inconsistent with an acute abdomen.

The plaintiff countered that mechanical bowel obstruction (not necessarily a rare volvulus) was always in the differential diagnosis for acute and severe abdominal pain, and the failure to perform plain radiography of the abdomen was in and of itself negligent. Plaintiff experts opined that had the providers in this case performed plain radiography as the standard of care required, FR’s rare diagnosis would have been discovered, even if by "accident."

Conclusion

Dr. Hospitalist documented a desire to obtain a plain abdominal radiograph, but he ordered it routine and therefore it was never performed prior to FR’s death. Had Dr. Hospitalist obtained the film STAT, more likely than not the volvulus would have been identified well within the window to get FR a surgical consult and to the operating room for treatment.

This case is another example of what turned out to be an incomplete workup from the ED in the setting of "uncontrolled pain" (see previous column). Admission for "pain control" is a red flag for an underlying disorder that has been missed by the initial ED evaluation. In this case, the workup should have reasonably included a plain radiograph of the abdomen. This case was eventually settled on behalf of the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

A diabetic foot infection progresses to amputation

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

The story

KL was a 56-year-old man with multiple comorbidities, including obesity, coronary artery disease, hypertension, insulin-dependent diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and dyslipidemia. He presented to Hospital A with fever and chills, along with an open wound on the bottom of his left foot. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 14,000 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. KL was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist for cellulitis and an infected diabetic foot ulcer.

KL was started on intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam and blood cultures were drawn. A bone scan was negative for osteomyelitis. Blood cultures did not grow any bacteria, but a wound culture from his foot ulcer grew Klebsiella. Dr. Hospitalist consulted inpatient podiatry for wound debridement, but KL apparently refused in favor of being seen by his own podiatrist as an outpatient. By hospital day 2, KL was afebrile, eating well, and he was discharged on oral ciprofloxacin later that same day.

Two days after discharge, KL followed up with his primary care physician (PCP). KL was again febrile and his foot ulcer looked worse. The PCP recommended hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics, but KL was reluctant to return to the hospital. The PCP arranged for midline placement and KL was referred to a local wound clinic for intravenous vancomycin to begin the next day. KL remained on the oral ciprofloxacin.

Over the next 3 days, KL received daily intravenous vancomycin at the wound clinic. However, the foot ulcer continued to drain purulent material with associated cellulitis and advancing erythema across the forefoot. The wound nurse contacted the PCP who had sent KL to the emergency department of Hospital B. Laboratory studies revealed a WBC 18,300 cells/mL and a serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL. KL was informed that he needed wound debridement and was offered the same podiatrist that he refused at Hospital A. Once again, KL deferred in favor of his own podiatrist who apparently was on vacation. Blood and wound cultures were obtained and KL received a dose of intravenous amoxicillin/sulbactam in the ED, but because of his refusal to receive wound debridement and care at Hospital A or B, he was sent home that same afternoon.

KL left Hospital B and drove 2 hours to the ED of Hospital C. He was immediately admitted and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam were begun. Plain films of the foot were consistent with osteomyelitis. An MRI of the foot demonstrated cellulitis, myositis, and a forefoot abscess. Within 24 hours of admission, KL developed chest pain and was subsequently ruled-in for a non–ST-elevation MI. KL ended up getting a left heart catheterization, and this delayed surgical debridement of his infected foot. Ultimately, KL did have debridement of his foot, but the infection had an advanced to the point that a below-the-knee amputation was required. Surgical pathology cultures were positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Complaint

KL was now facing life without his left leg, and he was angry and felt that the medical system had let him down. A complaint was quickly filed and alleged multiple breaches in the standard of care against multiple providers. The complaint included Dr. Hospitalist and asserted that he failed to obtain an MRI of the left foot from the very start, stopped intravenous vancomycin inappropriately, and failed to obtain infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults.

The complaint further asserted that the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B were negligent for not readmitting KL and obtaining infectious disease and orthopedic surgery consults. If the providers in this case had continued intravenous vancomycin throughout his case and otherwise obtained appropriate specialty care, KL’s leg would have been saved.

Scientific principles

Diabetic foot infections are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Important risk factors for development of diabetic foot infections include neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, and poor glycemic control. Most diabetic foot infections are polymicrobial, but MRSA is a common pathogen. Although severe diabetic foot infections warrant hospitalization for urgent surgical consultation, antimicrobial administration, and medical stabilization, most mild infections and many moderate infections can be managed in the outpatient setting with close follow-up.

The possibility of osteomyelitis should be considered in diabetic patients with foot wounds associated with signs of infection in the deeper soft tissues and in patients with chronic ulcers. Many patients with confirmed osteomyelitis of the foot benefit from surgical resection.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Although Dr. Hospitalist had a negative bone scan result, he should have considered MRSA as a pathogen for KL despite a wound culture growing Klebsiella only. Most experts agreed, however, that it would be pure speculation as to what an MRI would have shown so early in KL’s course and ultimately, Dr. Hospitalist was defensible because KL did have appropriate follow-up just 48 hours after discharge. In fact, more than 21 days from original presentation to his amputation, KL only had 3 days off of intravenous vancomycin.

As a result, defense experts focused on the failure of KL to obtain debridement as the main reason for his injury. Dr. Hospitalist, the PCP and the ED providers at Hospital B, all documented KL’s refusal to allow debridement by a podiatrist other than his own. KL denied this allegation, but the chart was consistent in this regard.

Conclusion

In the era of patient-centered care, patient wishes and preferences are important to integrate into the overall care plan. But when a patient’s wishes and preferences delay or otherwise subvert optimal care, it is vital that the hospitalist document the circumstances in their entirety. Documentation should confirm that the patient has capacity for decision making and that care recommendation benefits, risks for not following said recommendations, and care recommendation alternatives have been fully reviewed.

It is also helpful to have such discussions witnessed by other providers (that is, the nurse) so that the documentation is corroborated. The PCP and Hospital B were dismissed from the case. Hospital A settled with the plaintiff by waiving all hospital charges from his original hospitalization.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

A fatal ‘never event’

DB was a 22-year-old man who was brought to the hospital after he was found down in the street by police. Witnesses confirmed that DB was a pedestrian involved in a hit-and-run accident with a motor vehicle.