User login

Approximately 108 million individuals have been forcibly displaced across the globe as of 2022, 35 million of whom are formally designated as refugees.1,2 The United States has coordinated resettlement of more refugee populations than any other country; the most common countries of origin are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Afghanistan, and Myanmar.3 In 2021, policy to increase the number of refugees resettled in the United States by more than 700% (from 15,000 up to 125,000) was established; since enactment, the United States has seen more than double the refugee arrivals in 2023 than the prior year, making medical care for this population increasingly relevant for the dermatologist.4

Understanding how to care for this population begins with an accurate understanding of the term refugee. The United Nations defines a refugee as a person who is unwilling or unable to return to their country of nationality because of persecution or well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This term grants a protected status under international law and encompasses access to travel assistance, housing, cultural orientation, and medical evaluation upon resettlement.5,6

The burden of treatable dermatologic conditions in refugee populations ranges from 19% to 96% in the literature7,8 and varies from inflammatory disorders to infectious and parasitic diseases.9 In one study of 6899 displaced individuals in Greece, the prevalence of dermatologic conditions was higher than traumatic injury, cardiac disease, psychological conditions, and dental disease.10

When outlining differential diagnoses for parasitic infestations of the skin that affect refugee populations, helpful considerations include the individual’s country of origin, route traveled, and method of travel.11 Parasitic infestations specifically are more common in refugee populations when there are barriers to basic hygiene, crowded living or travel conditions, or lack of access to health care, which they may experience at any point in their home country, during travel, or in resettlement housing.8

Even with limited examination and diagnostic resources, the skin is the most accessible first indication of patients’ overall well-being and often provides simple diagnostic clues—in combination with contextualization of the patient’s unique circumstances—necessary for successful diagnosis and treatment of scabies and pediculosis.12 The dermatologist working with refugee populations may be the first set of eyes available and trained to discern skin infestations and therefore has the potential to improve overall outcomes.

Some parasitic infestations in refugee populations may fall under the category of neglected tropical diseases, including scabies, ascariasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and schistosomiasis; they affect an estimated 1 billion individuals across the globe but historically have been underrepresented in the literature and in health policy due in part to limited access to care.13 This review will focus on infestations by the scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis) and the human louse, as these frequently are encountered, easily diagnosed, and treatable by trained clinicians, even in resource-limited settings.

Scabies

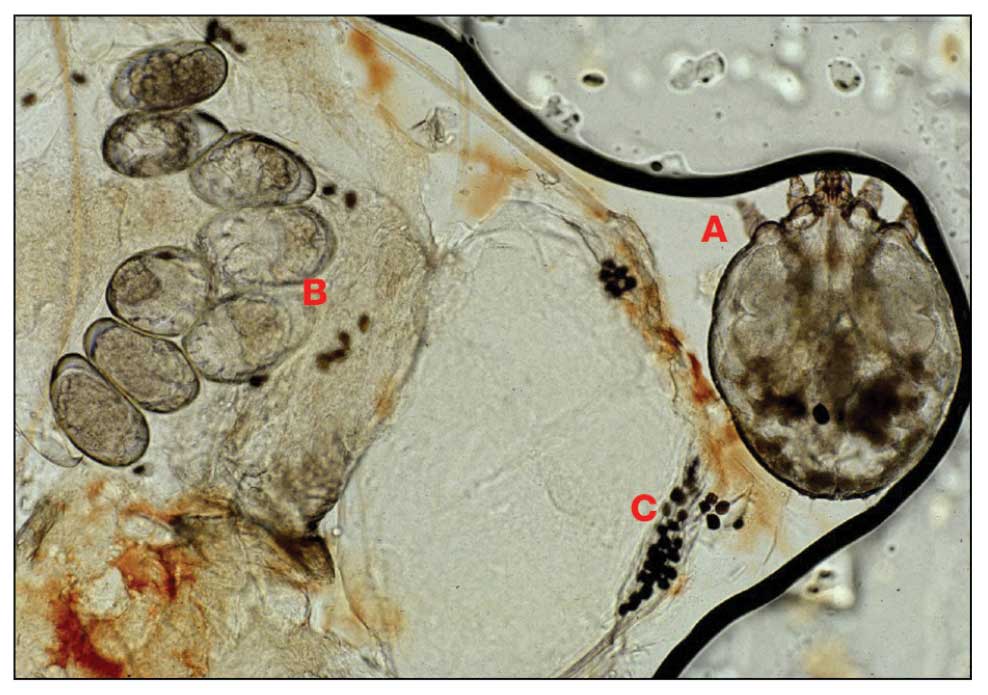

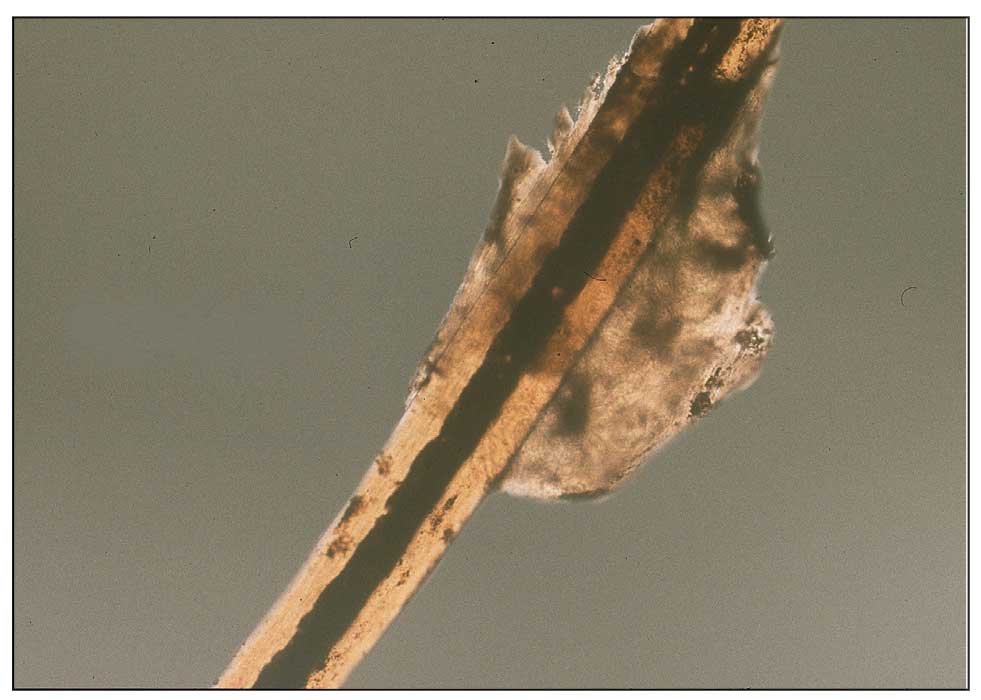

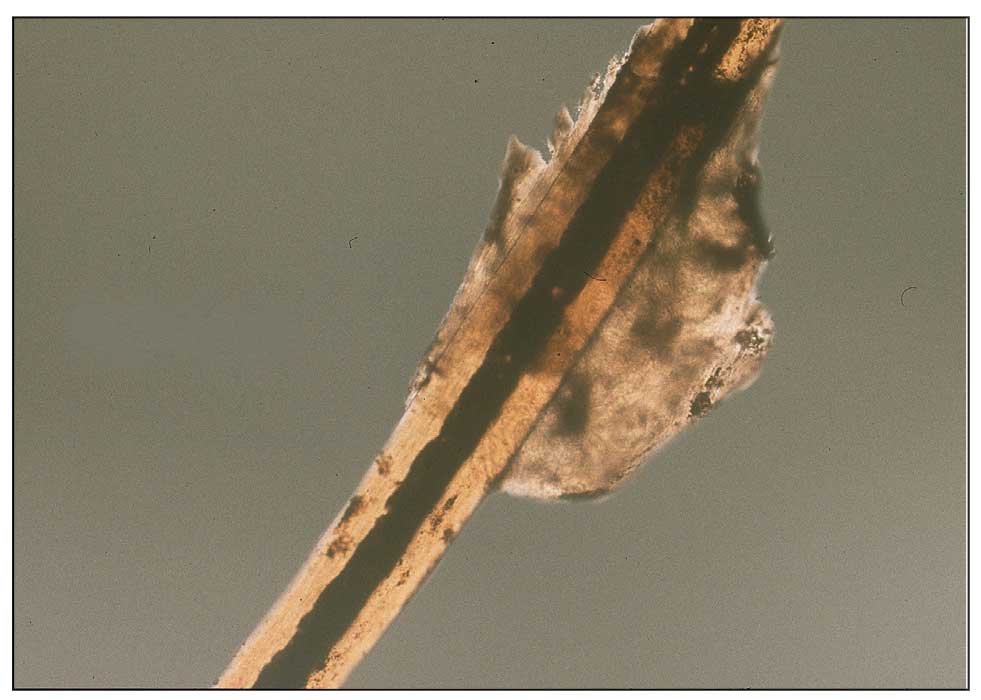

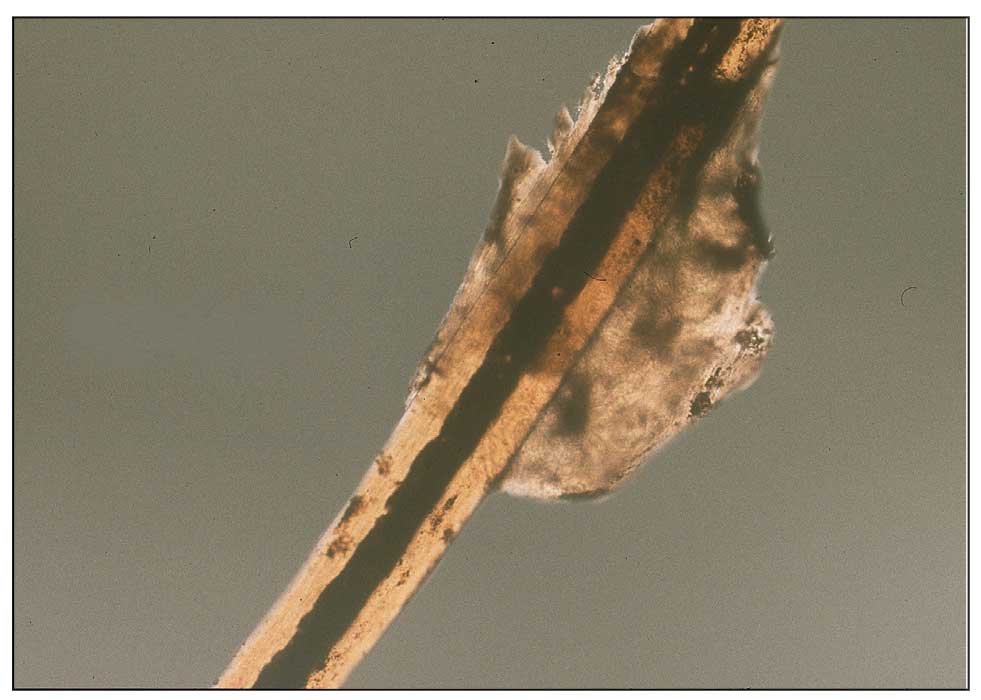

Scabies is a parasitic skin infestation caused by the 8-legged mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The female mite begins the infestation process via penetration of the epidermis, particularly the stratum corneum, and commences laying eggs (Figure 1). The subsequent larvae emerge 48 to 72 hours later and remain burrowed in the epidermis. The larvae mature over the next 10 to 14 days and continue the reproductive cycle.14,15 Symptoms of infestation occurs due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite and its by-products.16 Transmission of the mite primarily occurs via direct (skin-to-skin) contact with infected individuals or environmental surfaces for 24 to36 hours in specific conditions, though the latter source has been debated in the literature.

The method of transmission is particularly important when considering care for refugee populations. Scabies is found most often in those living in or traveling from tropical regions including East Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Latin America.17 In displaced or refugee populations, a lack of access to basic hygiene, extended travel in close quarters, and suboptimal health care access all may lead to an increased incidence of untreated scabies infestations.18 Scabies is more prevalent in children, with increased potential for secondary bacterial infections with Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species due to excoriation in unsanitary conditions. Secondary infection with Streptococcus pyogenes can lead to acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, which accounts for a large burden of chronic kidney disease in affected populations.19 However, scabies may be found in any population, regardless of hygiene or health care access. Treating health care providers should keep a broad differential.

Presentation—The latency of scabies symptoms is 2 to 6 weeks in a primary outbreak and may be as short as 1 to 3 days with re-infestation, following the course of delayed-type hypersensitivity.20 The initial hallmark symptom is pruritus with increased severity in the evening. Visible lesions, excoriations, and burrows associated with scattered vesicles or pustules may be seen over the web spaces of the hands and feet, volar surfaces of the wrists, axillae, waist, genitalia, inner thighs, or buttocks.19 Chronic infestation often manifests with genital nodules. In populations with limited access to health care, there are reports of a sensitization phenomenon in which the individual may become less symptomatic after 4 to 6 weeks and yet be a potential carrier of the mite.21

Those with compromised immune function, such as individuals living with HIV or severe malnutrition, may present with crusted scabies, a variant that manifests as widespread hyperkeratotic scaling with more pronounced involvement of the head, neck, and acral areas. In contrast to classic scabies, crusted scabies is associated with minimal pruritus.22

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of scabies is largely clinical with confirmation through skin scrapings. The International Alliance for Control of Scabies has established diagnostic criteria that include a combination of clinical findings, history, and visualization of mites.23 A dermatologist working with refugee populations may employ any combination of history (eg, nocturnal itch, exposure to an affected individual) or clinical findings along with a high degree of suspicion in those with elevated risk. Visualization of mites is helpful to confirm the diagnosis and may be completed with the application of mineral oil at the terminal end of a burrow, skin scraping with a surgical blade or needle, and examination under light microscopy.

Treatment—First-line treatment for scabies consists of application of permethrin cream 5% on the skin of the neck to the soles of the feet, which is to be left on for 8 to 14 hours followed by rinsing. Re-application is recommended in 1 to 2 weeks. Oral ivermectin is a reasonable alternative to permethrin cream due to its low cost and easy administration in large affected groups. It is not labeled for use in pregnant women or children weighing less than 15 kg but has no selective fetal toxicity. Treatment of scabies with ivermectin has the benefit of treating many other parasitic infections. Both medications are on the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medications and are widely available for treating providers, even in resource-limited settings.24

Much of the world still uses benzyl benzoate or precipitated sulfur ointment to treat scabies, and some botanicals used in folk medicine have genuine antiscabetic properties. Pruritus may persist for 1 to 4 weeks following treatment and does not indicate treatment failure. Topical camphor and menthol preparations, low-potency topical corticosteroids, or emollients all may be employed for relief.25 Sarna is a Spanish term for scabies and has become the proprietary name for topical antipruritic agents. Additional methods of treatment and prevention include washing clothes and linens in hot water and drying on high heat. If machine washing is not available, clothing and linens may be sealed in a plastic bag for 72 hours.

Pediculosis

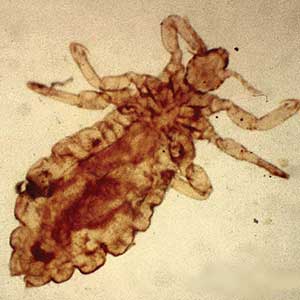

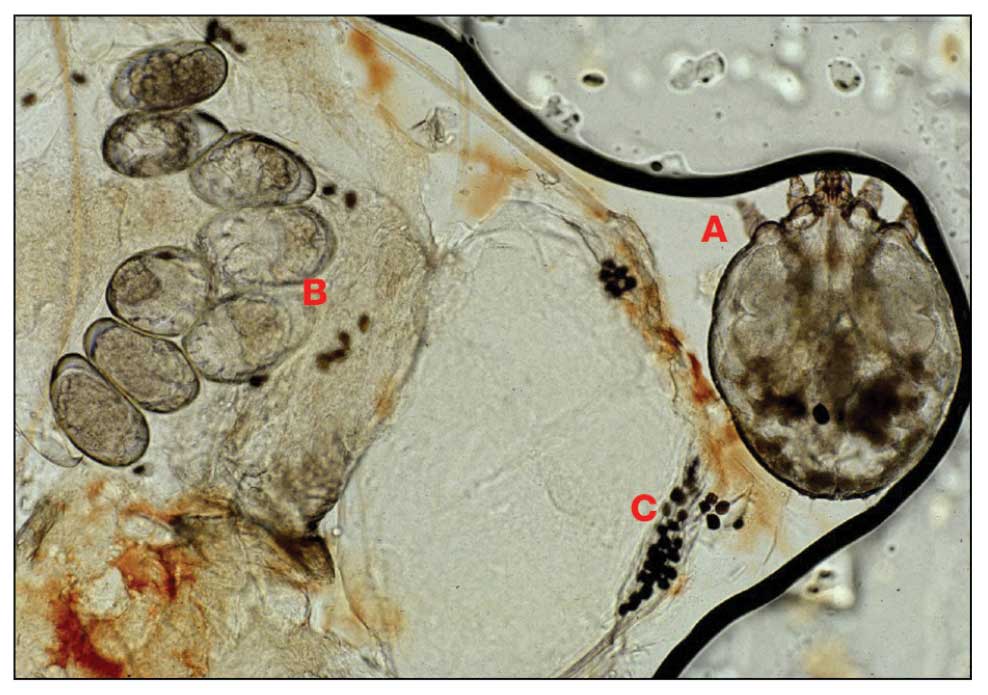

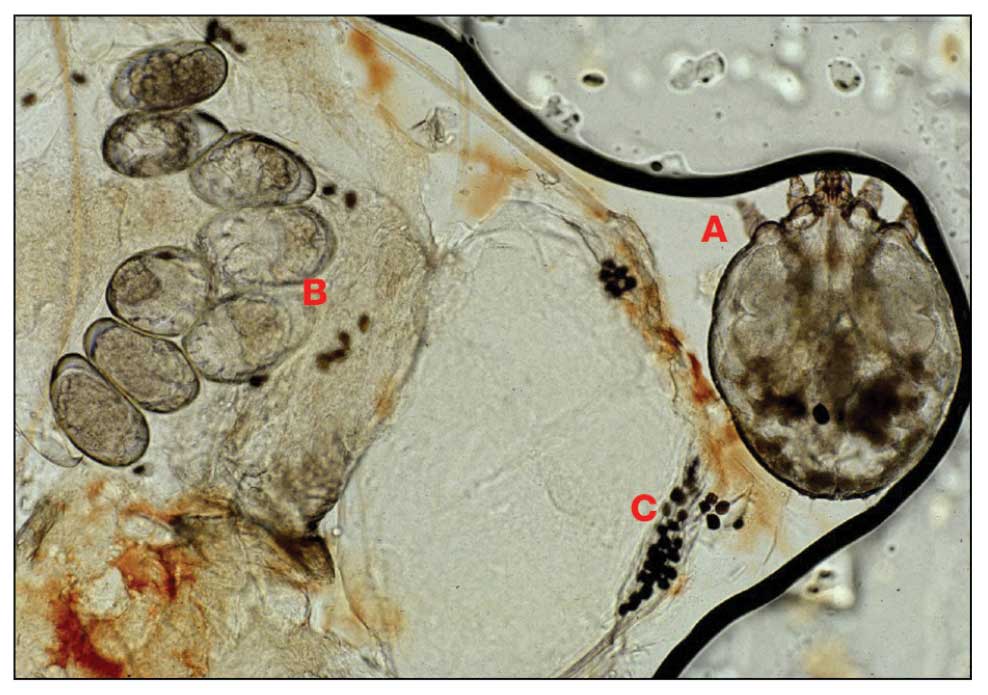

Pediculosis is an infestation caused by the ectoparasite Pediculus humanus, an obligate, sesame seed–sized louse that feeds exclusively on the blood of its host (Figure 2).26 Of the lice species, 2 require humans as hosts; one is P humanus and the other is Pthirus pubis (pubic lice). Pediculus humanus may be further classified into morphologies based largely on the affected area: body (P humanus corporis) or head (P humanus capitis), both of which will be discussed.27

Lice primarily attach to clothing and hair shafts, then transfer to the skin for blood feeds. Females lay eggs that hatch 6 to 10 days later, subsequently maturing into adults. The lifespan of these parasites with regular access to a host is 1 to 3 months for head lice and 18 days for body lice vs only 3 to 5 days without a host.28 Transmission of P humanus capitis primarily occurs via direct contact with affected individuals, either head-to-head contact or sharing of items such as brushes and headscarves; P humanus corporis also may be transmitted via direct contact with affected individuals or clothing.

Pediculosis is an important infestation to consider when providing care for refugee populations. Risk factors include lack of access to basic hygiene, including regular bathing or laundering of clothing, and crowded conditions that make direct person-to-person contact with affected individuals more likely.29 Body lice are associated more often with domestic turbulence and displaced populations30 in comparison to head lice, which have broad demographic variables, most often affecting females and children.28 Fatty acids in adult male sebum make the scalp less hospitable to lice.

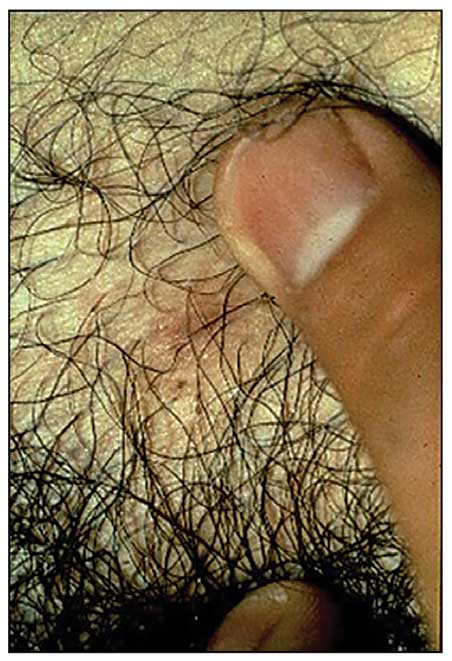

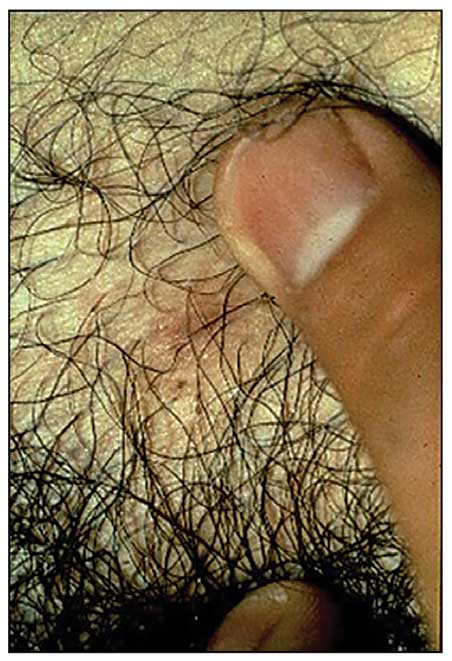

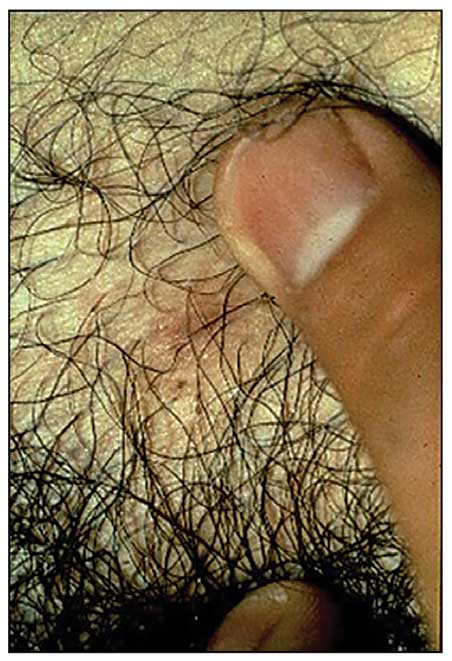

Presentation—The most common clinical manifestation of pediculosis is pruritus. Cutaneous findings can include papules, wheals, or hemorrhagic puncta secondary to the louse bite. Due to the Tyndall effect of deep hemosiderin pigment, blue-grey macules termed maculae ceruleae (Figure 3) also may be present in chronic infestations of pediculosis pubis, in contrast to pediculosis capitis or corporis.31 Body louse infestation is associated with a general pruritus concentrated on the neck, shoulders, and waist—areas where clothing makes the most direct contact. Lesions may be visible and include eczematous patches with excoriation and possible secondary bacterial infection. Chronic infestation may exhibit lichenification or hyperpigmentation in associated areas. Head lice most often manifest with localized scalp pruritus and associated excoriation and cervical or occipital lymphadenopathy.32

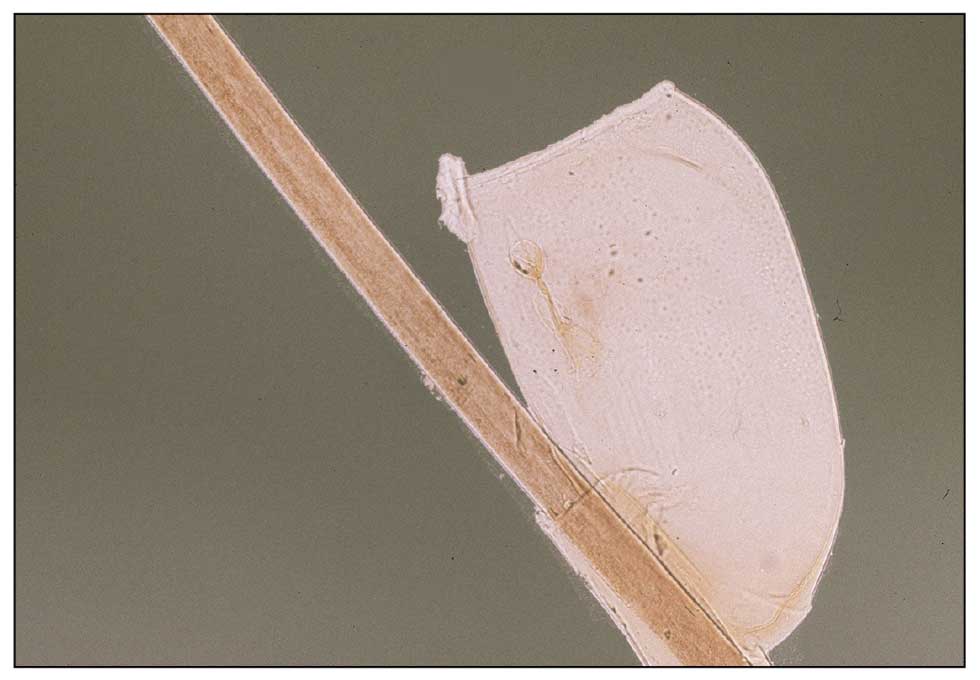

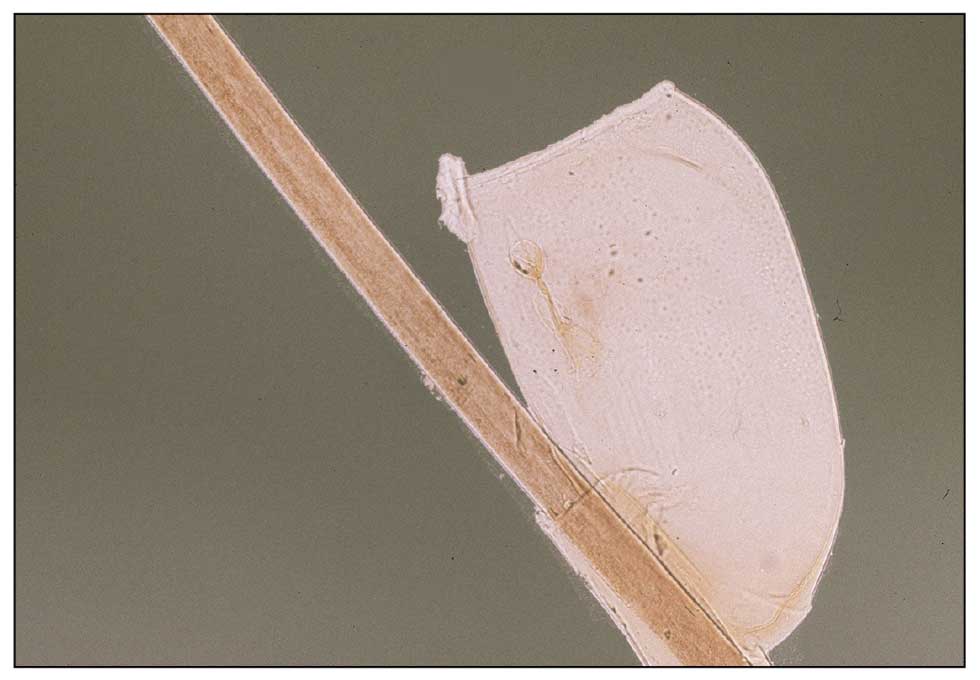

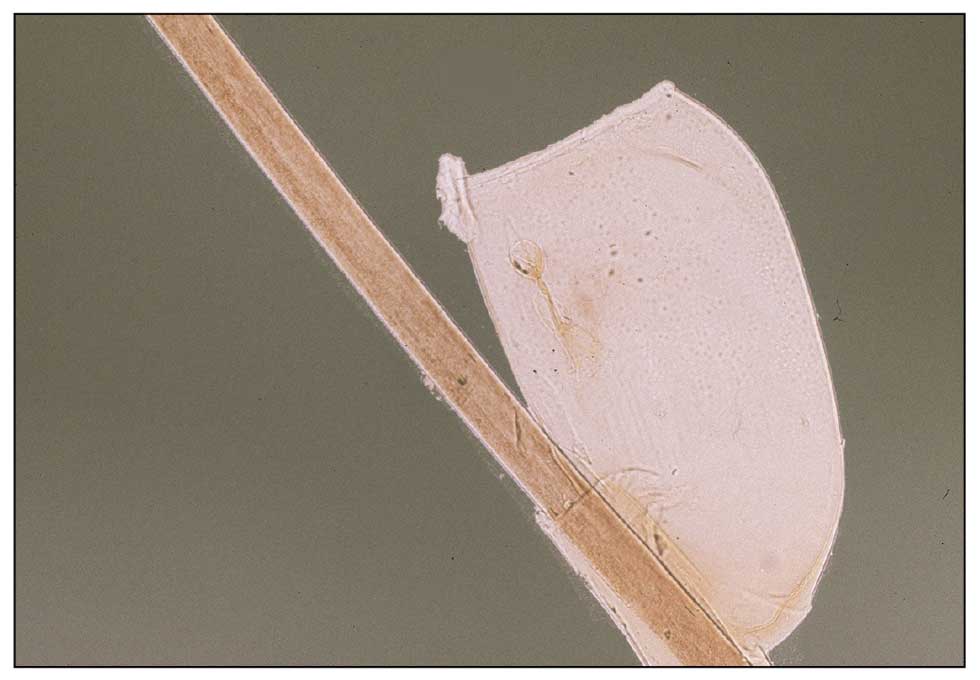

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of pediculosis is clinical, with confirmation requiring direct examination of the insect or nits (the egg case of the parasite)(Figure 4). Body lice and associated nits can be visualized on clothing seams near areas of highest body temperature, particularly the waistband. Head lice may be visualized crawling on hair shafts or on a louse comb. Nits are firmly attached to hair shafts and are visible to the naked eye, whereas pseudonits slide freely along the hair shaft and are not a manifestation of louse infestation (Figure 5).31

Treatment—Treatment varies by affected area. Pediculosis corporis may be treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the entire body and left on for 8 to 10 hours, but this may not be necessary if facilities are available to wash and dry clothing.33 The use of oral ivermectin and permethrin-impregnated underwear both have been proposed.34,35 Treatment of pediculosis capitis may be accomplished with a variety of topical pediculicides including permethrin, pyrethrum with piperonyl butoxide, dimethicone, malathion, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and topical ivermectin.22 Topical corticosteroids or emollients may be employed for residual pruritus.

Equally important is environmental elimination of infestation. Clothing should be discarded if possible or washed and dried using high heat. If neither approach is possible or appropriate, clothing may be sealed in a plastic bag for 2 weeks or treated with a pediculicide. Nit combing is an important adjunct in the treatment of pediculosis capitis.36 It is important to encourage return to work and/or school immediately after treatment. “No nit” policies are more harmful to education than helpful for prevention of investation.37

Pediculosis corporis may transmit infectious agents including Bartonella quintana, (trench fever, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), and Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus).31,38,39 Additionally, severe pediculosis infestations have the potential to cause chronic blood loss in affected populations. In a study of patients with active pediculosis infestation, mean hemoglobin values were found to be 2.5 g/dL lower than a matched population without infestation.40 It is important to consider pediculosis as a risk for iron-deficiency anemia in populations who are known to lack access to regular medical evaluation.41

Future Considerations

Increased access to tools and education for clinicians treating refugee populations is key to reducing the burden of parasitic skin disease and related morbidity and mortality in vulnerable groups both domestically and globally. One such tool, the Skin NTDs App, was launched by the World Health Organization in 2020. It is available for free for Android and iOS devices to assist clinicians in the field with the diagnosis and treatment of neglected tropical diseases—including scabies—that may affect refugee populations.42

Additionally, to both improve access and limit preventable sequelae, future investigations into appropriate models of community-based care are paramount. The model of community-based care is centered on the idea of care provision that prioritizes safety, accessibility, affordability, and acceptability in an environment closest to vulnerable populations. The largest dermatologic society, the International League of Dermatological Societies, formed a Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group that prioritizes understanding and improving care for refugee and migrant populations; this group hosted a summit in 2022, bringing together international subject matter leaders to discuss such models of care and set goals for the creation of tool kits for patients, frontline health care workers, and dermatologists.43

Conclusion

Improvement in dermatologic care of refugee populations includes provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate care by trained clinicians, adequate access to the most essential medications, and basic physical or legal access to health care systems in general.8,11,44 Parasitic infestations have the potential to remain asymptomatic for extended periods of time and result in spread to potentially nonendemic regions of resettlement.45 Additionally, the psychosocial well-being of refugee populations upon resettlement may be negatively affected by stigma of disease processes such as scabies and pediculosis, leading to additional barriers to successful re-entry into the patient’s new environment.46 Therefore, proper screening, diagnosis, and treatment of the most common parasitic infestations in this population have great potential to improve outcomes for large groups across the globe.

- Monin K, Batalova J, Lai T. Refugees and Asylees in the United States. Migration Information Source. Published May 13, 2021. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states-2021

- UNHCR. Figures at a Glance. UNHCR USA. Update June 14, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

- UNHCR. Refugee resettlement facts. Published October 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/refugee-resettlement-facts

- US Department of State. Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2024. Published November 3, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.state.gov/report-to-congress-on-proposed-refugee-admissions-for-fiscal-year-2024/

- UNHCR. Compact for Migration: Definitions. United Nations. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Published December 2010. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

- Kibar Öztürk M. Skin diseases in rural Nyala, Sudan (in a rural hospital, in 12 orphanages, and in two refugee camps). Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1341-1349. doi:10.1111/ijd.14619

- Padovese V, Knapp A. Challenges of managing skin diseases in refugees and migrants. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:101-115. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.08.010

- Saikal SL, Ge L, Mir A, et al. Skin disease profile of Syrian refugees in Jordan: a field-mission assessment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:419-425. doi:10.1111/jdv.15909

- Eonomopoulou A, Pavli A, Stasinopoulou P, et al. Migrant screening: lessons learned from the migrant holding level at the Greek-Turkish borders. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:177-184. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.012

- Marano N, Angelo KM, Merrill RD, et al. Expanding travel medicine in the 21st century to address the health needs of the world’s migrants.J Travel Med. 2018;25. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay067

- Hay RJ, Asiedu K. Skin-related neglected tropical diseases (skin NTDs)—a new challenge. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;4. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4010004

- NIAID. Neglected tropical diseases. Updated July 11, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/neglected-tropical-diseases

- Arlian LG, Morgan MS. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:297. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1

- Arlian LG, Runyan RA, Achar S, et al. Survival and infectivity of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis and var. hominis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):210-215. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70151-4

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Mellanby K, Johnson CG, Bartley WC. Treatment of scabies. Br Med J. 1942;2:1-4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4252.1

- Walton SF. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to scabies. Parasit Immunol. 2010;32:532-540. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01218.x

- Coates SJ, Thomas C, Chosidow O, et al. Ectoparasites: pediculosis and tungiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:551-569. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.110

- Engelman D, Fuller LC, Steer AC; International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Delphi p. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of scabies: a Delphi study of international experts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006549. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006549

- World Health Organization. WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines—23rd list, 2023. Updated July 26, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.02

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, et al. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1248-1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Badiaga S, Brouqui P. Human louse-transmitted infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:332-337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03778.x

- Leo NP, Campbell NJH, Yang X, et al. Evidence from mitochondrial DNA that head lice and body lice of humans (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) are conspecific. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:662-666. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-39.4.662

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)09458-1

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Détrez M-A, et al. Prevalences of scabies and pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112. doi:10.1111/bjd.14226

- Brouqui P. Arthropod-borne diseases associated with political and social disorder. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:357-374. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144739

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02729-4

- Bloomfield D. Head lice. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:34-35; discussion 34-35. doi:10.1542/pir.23-1-34

- Stone SP GJ, Bacelieri RE. Scabies, other mites, and pediculosis. In: Wolf K GL, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw Hill; 2008:2029.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476. doi:10.1086/499279

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6398

- CDC. Parasites: Treatment. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/treatment.html

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1355-e1365. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0746

- Ohl ME, Spach DH. Bartonella quintana and urban trench fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:131-135. doi:10.1086/313890

- Drali R, Sangaré AK, Boutellis A, et al. Bartonella quintana in body lice from scalp hair of homeless persons, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:907-908. doi:10.3201/eid2005.131242

- Rudd N, Zakaria A, Kohn MA, et al. Association of body lice infestation with hemoglobin values in hospitalized dermatology patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:691-693. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0818

- Guss DA, Koenig M, Castillo EM. Severe iron deficiency anemia and lice infestation. J Emergency Med. 2011;41:362-365. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.030

- Neglected tropical diseases of the skin: WHO launches mobile application to facilitate diagnosis. News release. World Health Organization; July 16, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/16-07-2020-neglected-tropical-diseases-of-the-skin-who-launches-mobile-application-to-facilitate-diagnosis

- Padovese V, Fuller LC, Griffiths CEM, et al; Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group of the International Foundation for Dermatology. Migrant skin health: perspectives from the Migrant Health Summit, Malta, 2022. Br J Dermatology. 2023;188:553-554. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad001

- Knapp AP, Rehmus W, Chang AY. Skin diseases in displaced populations: a review of contributing factors, challenges, and approaches to care. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1299-1311. doi:10.1111/ijd.15063

- Norman FF, Comeche B, Chamorro S, et al. Overcoming challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of parasitic infectious diseases in migrants. Expert Rev Anti-infective Therapy. 2020;18:127-143. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1713099

- Skin NTDs: prioritizing integrated approaches to reduce suffering, psychosocial impact and stigmatization. News release. World Health Organization; October 29, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2020-skin-ntds-prioritizing-integrated-approaches-to-reduce-suffering-psychosocial-impact-and-stigmatization

Approximately 108 million individuals have been forcibly displaced across the globe as of 2022, 35 million of whom are formally designated as refugees.1,2 The United States has coordinated resettlement of more refugee populations than any other country; the most common countries of origin are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Afghanistan, and Myanmar.3 In 2021, policy to increase the number of refugees resettled in the United States by more than 700% (from 15,000 up to 125,000) was established; since enactment, the United States has seen more than double the refugee arrivals in 2023 than the prior year, making medical care for this population increasingly relevant for the dermatologist.4

Understanding how to care for this population begins with an accurate understanding of the term refugee. The United Nations defines a refugee as a person who is unwilling or unable to return to their country of nationality because of persecution or well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This term grants a protected status under international law and encompasses access to travel assistance, housing, cultural orientation, and medical evaluation upon resettlement.5,6

The burden of treatable dermatologic conditions in refugee populations ranges from 19% to 96% in the literature7,8 and varies from inflammatory disorders to infectious and parasitic diseases.9 In one study of 6899 displaced individuals in Greece, the prevalence of dermatologic conditions was higher than traumatic injury, cardiac disease, psychological conditions, and dental disease.10

When outlining differential diagnoses for parasitic infestations of the skin that affect refugee populations, helpful considerations include the individual’s country of origin, route traveled, and method of travel.11 Parasitic infestations specifically are more common in refugee populations when there are barriers to basic hygiene, crowded living or travel conditions, or lack of access to health care, which they may experience at any point in their home country, during travel, or in resettlement housing.8

Even with limited examination and diagnostic resources, the skin is the most accessible first indication of patients’ overall well-being and often provides simple diagnostic clues—in combination with contextualization of the patient’s unique circumstances—necessary for successful diagnosis and treatment of scabies and pediculosis.12 The dermatologist working with refugee populations may be the first set of eyes available and trained to discern skin infestations and therefore has the potential to improve overall outcomes.

Some parasitic infestations in refugee populations may fall under the category of neglected tropical diseases, including scabies, ascariasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and schistosomiasis; they affect an estimated 1 billion individuals across the globe but historically have been underrepresented in the literature and in health policy due in part to limited access to care.13 This review will focus on infestations by the scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis) and the human louse, as these frequently are encountered, easily diagnosed, and treatable by trained clinicians, even in resource-limited settings.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic skin infestation caused by the 8-legged mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The female mite begins the infestation process via penetration of the epidermis, particularly the stratum corneum, and commences laying eggs (Figure 1). The subsequent larvae emerge 48 to 72 hours later and remain burrowed in the epidermis. The larvae mature over the next 10 to 14 days and continue the reproductive cycle.14,15 Symptoms of infestation occurs due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite and its by-products.16 Transmission of the mite primarily occurs via direct (skin-to-skin) contact with infected individuals or environmental surfaces for 24 to36 hours in specific conditions, though the latter source has been debated in the literature.

The method of transmission is particularly important when considering care for refugee populations. Scabies is found most often in those living in or traveling from tropical regions including East Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Latin America.17 In displaced or refugee populations, a lack of access to basic hygiene, extended travel in close quarters, and suboptimal health care access all may lead to an increased incidence of untreated scabies infestations.18 Scabies is more prevalent in children, with increased potential for secondary bacterial infections with Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species due to excoriation in unsanitary conditions. Secondary infection with Streptococcus pyogenes can lead to acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, which accounts for a large burden of chronic kidney disease in affected populations.19 However, scabies may be found in any population, regardless of hygiene or health care access. Treating health care providers should keep a broad differential.

Presentation—The latency of scabies symptoms is 2 to 6 weeks in a primary outbreak and may be as short as 1 to 3 days with re-infestation, following the course of delayed-type hypersensitivity.20 The initial hallmark symptom is pruritus with increased severity in the evening. Visible lesions, excoriations, and burrows associated with scattered vesicles or pustules may be seen over the web spaces of the hands and feet, volar surfaces of the wrists, axillae, waist, genitalia, inner thighs, or buttocks.19 Chronic infestation often manifests with genital nodules. In populations with limited access to health care, there are reports of a sensitization phenomenon in which the individual may become less symptomatic after 4 to 6 weeks and yet be a potential carrier of the mite.21

Those with compromised immune function, such as individuals living with HIV or severe malnutrition, may present with crusted scabies, a variant that manifests as widespread hyperkeratotic scaling with more pronounced involvement of the head, neck, and acral areas. In contrast to classic scabies, crusted scabies is associated with minimal pruritus.22

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of scabies is largely clinical with confirmation through skin scrapings. The International Alliance for Control of Scabies has established diagnostic criteria that include a combination of clinical findings, history, and visualization of mites.23 A dermatologist working with refugee populations may employ any combination of history (eg, nocturnal itch, exposure to an affected individual) or clinical findings along with a high degree of suspicion in those with elevated risk. Visualization of mites is helpful to confirm the diagnosis and may be completed with the application of mineral oil at the terminal end of a burrow, skin scraping with a surgical blade or needle, and examination under light microscopy.

Treatment—First-line treatment for scabies consists of application of permethrin cream 5% on the skin of the neck to the soles of the feet, which is to be left on for 8 to 14 hours followed by rinsing. Re-application is recommended in 1 to 2 weeks. Oral ivermectin is a reasonable alternative to permethrin cream due to its low cost and easy administration in large affected groups. It is not labeled for use in pregnant women or children weighing less than 15 kg but has no selective fetal toxicity. Treatment of scabies with ivermectin has the benefit of treating many other parasitic infections. Both medications are on the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medications and are widely available for treating providers, even in resource-limited settings.24

Much of the world still uses benzyl benzoate or precipitated sulfur ointment to treat scabies, and some botanicals used in folk medicine have genuine antiscabetic properties. Pruritus may persist for 1 to 4 weeks following treatment and does not indicate treatment failure. Topical camphor and menthol preparations, low-potency topical corticosteroids, or emollients all may be employed for relief.25 Sarna is a Spanish term for scabies and has become the proprietary name for topical antipruritic agents. Additional methods of treatment and prevention include washing clothes and linens in hot water and drying on high heat. If machine washing is not available, clothing and linens may be sealed in a plastic bag for 72 hours.

Pediculosis

Pediculosis is an infestation caused by the ectoparasite Pediculus humanus, an obligate, sesame seed–sized louse that feeds exclusively on the blood of its host (Figure 2).26 Of the lice species, 2 require humans as hosts; one is P humanus and the other is Pthirus pubis (pubic lice). Pediculus humanus may be further classified into morphologies based largely on the affected area: body (P humanus corporis) or head (P humanus capitis), both of which will be discussed.27

Lice primarily attach to clothing and hair shafts, then transfer to the skin for blood feeds. Females lay eggs that hatch 6 to 10 days later, subsequently maturing into adults. The lifespan of these parasites with regular access to a host is 1 to 3 months for head lice and 18 days for body lice vs only 3 to 5 days without a host.28 Transmission of P humanus capitis primarily occurs via direct contact with affected individuals, either head-to-head contact or sharing of items such as brushes and headscarves; P humanus corporis also may be transmitted via direct contact with affected individuals or clothing.

Pediculosis is an important infestation to consider when providing care for refugee populations. Risk factors include lack of access to basic hygiene, including regular bathing or laundering of clothing, and crowded conditions that make direct person-to-person contact with affected individuals more likely.29 Body lice are associated more often with domestic turbulence and displaced populations30 in comparison to head lice, which have broad demographic variables, most often affecting females and children.28 Fatty acids in adult male sebum make the scalp less hospitable to lice.

Presentation—The most common clinical manifestation of pediculosis is pruritus. Cutaneous findings can include papules, wheals, or hemorrhagic puncta secondary to the louse bite. Due to the Tyndall effect of deep hemosiderin pigment, blue-grey macules termed maculae ceruleae (Figure 3) also may be present in chronic infestations of pediculosis pubis, in contrast to pediculosis capitis or corporis.31 Body louse infestation is associated with a general pruritus concentrated on the neck, shoulders, and waist—areas where clothing makes the most direct contact. Lesions may be visible and include eczematous patches with excoriation and possible secondary bacterial infection. Chronic infestation may exhibit lichenification or hyperpigmentation in associated areas. Head lice most often manifest with localized scalp pruritus and associated excoriation and cervical or occipital lymphadenopathy.32

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of pediculosis is clinical, with confirmation requiring direct examination of the insect or nits (the egg case of the parasite)(Figure 4). Body lice and associated nits can be visualized on clothing seams near areas of highest body temperature, particularly the waistband. Head lice may be visualized crawling on hair shafts or on a louse comb. Nits are firmly attached to hair shafts and are visible to the naked eye, whereas pseudonits slide freely along the hair shaft and are not a manifestation of louse infestation (Figure 5).31

Treatment—Treatment varies by affected area. Pediculosis corporis may be treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the entire body and left on for 8 to 10 hours, but this may not be necessary if facilities are available to wash and dry clothing.33 The use of oral ivermectin and permethrin-impregnated underwear both have been proposed.34,35 Treatment of pediculosis capitis may be accomplished with a variety of topical pediculicides including permethrin, pyrethrum with piperonyl butoxide, dimethicone, malathion, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and topical ivermectin.22 Topical corticosteroids or emollients may be employed for residual pruritus.

Equally important is environmental elimination of infestation. Clothing should be discarded if possible or washed and dried using high heat. If neither approach is possible or appropriate, clothing may be sealed in a plastic bag for 2 weeks or treated with a pediculicide. Nit combing is an important adjunct in the treatment of pediculosis capitis.36 It is important to encourage return to work and/or school immediately after treatment. “No nit” policies are more harmful to education than helpful for prevention of investation.37

Pediculosis corporis may transmit infectious agents including Bartonella quintana, (trench fever, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), and Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus).31,38,39 Additionally, severe pediculosis infestations have the potential to cause chronic blood loss in affected populations. In a study of patients with active pediculosis infestation, mean hemoglobin values were found to be 2.5 g/dL lower than a matched population without infestation.40 It is important to consider pediculosis as a risk for iron-deficiency anemia in populations who are known to lack access to regular medical evaluation.41

Future Considerations

Increased access to tools and education for clinicians treating refugee populations is key to reducing the burden of parasitic skin disease and related morbidity and mortality in vulnerable groups both domestically and globally. One such tool, the Skin NTDs App, was launched by the World Health Organization in 2020. It is available for free for Android and iOS devices to assist clinicians in the field with the diagnosis and treatment of neglected tropical diseases—including scabies—that may affect refugee populations.42

Additionally, to both improve access and limit preventable sequelae, future investigations into appropriate models of community-based care are paramount. The model of community-based care is centered on the idea of care provision that prioritizes safety, accessibility, affordability, and acceptability in an environment closest to vulnerable populations. The largest dermatologic society, the International League of Dermatological Societies, formed a Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group that prioritizes understanding and improving care for refugee and migrant populations; this group hosted a summit in 2022, bringing together international subject matter leaders to discuss such models of care and set goals for the creation of tool kits for patients, frontline health care workers, and dermatologists.43

Conclusion

Improvement in dermatologic care of refugee populations includes provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate care by trained clinicians, adequate access to the most essential medications, and basic physical or legal access to health care systems in general.8,11,44 Parasitic infestations have the potential to remain asymptomatic for extended periods of time and result in spread to potentially nonendemic regions of resettlement.45 Additionally, the psychosocial well-being of refugee populations upon resettlement may be negatively affected by stigma of disease processes such as scabies and pediculosis, leading to additional barriers to successful re-entry into the patient’s new environment.46 Therefore, proper screening, diagnosis, and treatment of the most common parasitic infestations in this population have great potential to improve outcomes for large groups across the globe.

Approximately 108 million individuals have been forcibly displaced across the globe as of 2022, 35 million of whom are formally designated as refugees.1,2 The United States has coordinated resettlement of more refugee populations than any other country; the most common countries of origin are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Afghanistan, and Myanmar.3 In 2021, policy to increase the number of refugees resettled in the United States by more than 700% (from 15,000 up to 125,000) was established; since enactment, the United States has seen more than double the refugee arrivals in 2023 than the prior year, making medical care for this population increasingly relevant for the dermatologist.4

Understanding how to care for this population begins with an accurate understanding of the term refugee. The United Nations defines a refugee as a person who is unwilling or unable to return to their country of nationality because of persecution or well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. This term grants a protected status under international law and encompasses access to travel assistance, housing, cultural orientation, and medical evaluation upon resettlement.5,6

The burden of treatable dermatologic conditions in refugee populations ranges from 19% to 96% in the literature7,8 and varies from inflammatory disorders to infectious and parasitic diseases.9 In one study of 6899 displaced individuals in Greece, the prevalence of dermatologic conditions was higher than traumatic injury, cardiac disease, psychological conditions, and dental disease.10

When outlining differential diagnoses for parasitic infestations of the skin that affect refugee populations, helpful considerations include the individual’s country of origin, route traveled, and method of travel.11 Parasitic infestations specifically are more common in refugee populations when there are barriers to basic hygiene, crowded living or travel conditions, or lack of access to health care, which they may experience at any point in their home country, during travel, or in resettlement housing.8

Even with limited examination and diagnostic resources, the skin is the most accessible first indication of patients’ overall well-being and often provides simple diagnostic clues—in combination with contextualization of the patient’s unique circumstances—necessary for successful diagnosis and treatment of scabies and pediculosis.12 The dermatologist working with refugee populations may be the first set of eyes available and trained to discern skin infestations and therefore has the potential to improve overall outcomes.

Some parasitic infestations in refugee populations may fall under the category of neglected tropical diseases, including scabies, ascariasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and schistosomiasis; they affect an estimated 1 billion individuals across the globe but historically have been underrepresented in the literature and in health policy due in part to limited access to care.13 This review will focus on infestations by the scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis) and the human louse, as these frequently are encountered, easily diagnosed, and treatable by trained clinicians, even in resource-limited settings.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic skin infestation caused by the 8-legged mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The female mite begins the infestation process via penetration of the epidermis, particularly the stratum corneum, and commences laying eggs (Figure 1). The subsequent larvae emerge 48 to 72 hours later and remain burrowed in the epidermis. The larvae mature over the next 10 to 14 days and continue the reproductive cycle.14,15 Symptoms of infestation occurs due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite and its by-products.16 Transmission of the mite primarily occurs via direct (skin-to-skin) contact with infected individuals or environmental surfaces for 24 to36 hours in specific conditions, though the latter source has been debated in the literature.

The method of transmission is particularly important when considering care for refugee populations. Scabies is found most often in those living in or traveling from tropical regions including East Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Latin America.17 In displaced or refugee populations, a lack of access to basic hygiene, extended travel in close quarters, and suboptimal health care access all may lead to an increased incidence of untreated scabies infestations.18 Scabies is more prevalent in children, with increased potential for secondary bacterial infections with Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species due to excoriation in unsanitary conditions. Secondary infection with Streptococcus pyogenes can lead to acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, which accounts for a large burden of chronic kidney disease in affected populations.19 However, scabies may be found in any population, regardless of hygiene or health care access. Treating health care providers should keep a broad differential.

Presentation—The latency of scabies symptoms is 2 to 6 weeks in a primary outbreak and may be as short as 1 to 3 days with re-infestation, following the course of delayed-type hypersensitivity.20 The initial hallmark symptom is pruritus with increased severity in the evening. Visible lesions, excoriations, and burrows associated with scattered vesicles or pustules may be seen over the web spaces of the hands and feet, volar surfaces of the wrists, axillae, waist, genitalia, inner thighs, or buttocks.19 Chronic infestation often manifests with genital nodules. In populations with limited access to health care, there are reports of a sensitization phenomenon in which the individual may become less symptomatic after 4 to 6 weeks and yet be a potential carrier of the mite.21

Those with compromised immune function, such as individuals living with HIV or severe malnutrition, may present with crusted scabies, a variant that manifests as widespread hyperkeratotic scaling with more pronounced involvement of the head, neck, and acral areas. In contrast to classic scabies, crusted scabies is associated with minimal pruritus.22

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of scabies is largely clinical with confirmation through skin scrapings. The International Alliance for Control of Scabies has established diagnostic criteria that include a combination of clinical findings, history, and visualization of mites.23 A dermatologist working with refugee populations may employ any combination of history (eg, nocturnal itch, exposure to an affected individual) or clinical findings along with a high degree of suspicion in those with elevated risk. Visualization of mites is helpful to confirm the diagnosis and may be completed with the application of mineral oil at the terminal end of a burrow, skin scraping with a surgical blade or needle, and examination under light microscopy.

Treatment—First-line treatment for scabies consists of application of permethrin cream 5% on the skin of the neck to the soles of the feet, which is to be left on for 8 to 14 hours followed by rinsing. Re-application is recommended in 1 to 2 weeks. Oral ivermectin is a reasonable alternative to permethrin cream due to its low cost and easy administration in large affected groups. It is not labeled for use in pregnant women or children weighing less than 15 kg but has no selective fetal toxicity. Treatment of scabies with ivermectin has the benefit of treating many other parasitic infections. Both medications are on the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medications and are widely available for treating providers, even in resource-limited settings.24

Much of the world still uses benzyl benzoate or precipitated sulfur ointment to treat scabies, and some botanicals used in folk medicine have genuine antiscabetic properties. Pruritus may persist for 1 to 4 weeks following treatment and does not indicate treatment failure. Topical camphor and menthol preparations, low-potency topical corticosteroids, or emollients all may be employed for relief.25 Sarna is a Spanish term for scabies and has become the proprietary name for topical antipruritic agents. Additional methods of treatment and prevention include washing clothes and linens in hot water and drying on high heat. If machine washing is not available, clothing and linens may be sealed in a plastic bag for 72 hours.

Pediculosis

Pediculosis is an infestation caused by the ectoparasite Pediculus humanus, an obligate, sesame seed–sized louse that feeds exclusively on the blood of its host (Figure 2).26 Of the lice species, 2 require humans as hosts; one is P humanus and the other is Pthirus pubis (pubic lice). Pediculus humanus may be further classified into morphologies based largely on the affected area: body (P humanus corporis) or head (P humanus capitis), both of which will be discussed.27

Lice primarily attach to clothing and hair shafts, then transfer to the skin for blood feeds. Females lay eggs that hatch 6 to 10 days later, subsequently maturing into adults. The lifespan of these parasites with regular access to a host is 1 to 3 months for head lice and 18 days for body lice vs only 3 to 5 days without a host.28 Transmission of P humanus capitis primarily occurs via direct contact with affected individuals, either head-to-head contact or sharing of items such as brushes and headscarves; P humanus corporis also may be transmitted via direct contact with affected individuals or clothing.

Pediculosis is an important infestation to consider when providing care for refugee populations. Risk factors include lack of access to basic hygiene, including regular bathing or laundering of clothing, and crowded conditions that make direct person-to-person contact with affected individuals more likely.29 Body lice are associated more often with domestic turbulence and displaced populations30 in comparison to head lice, which have broad demographic variables, most often affecting females and children.28 Fatty acids in adult male sebum make the scalp less hospitable to lice.

Presentation—The most common clinical manifestation of pediculosis is pruritus. Cutaneous findings can include papules, wheals, or hemorrhagic puncta secondary to the louse bite. Due to the Tyndall effect of deep hemosiderin pigment, blue-grey macules termed maculae ceruleae (Figure 3) also may be present in chronic infestations of pediculosis pubis, in contrast to pediculosis capitis or corporis.31 Body louse infestation is associated with a general pruritus concentrated on the neck, shoulders, and waist—areas where clothing makes the most direct contact. Lesions may be visible and include eczematous patches with excoriation and possible secondary bacterial infection. Chronic infestation may exhibit lichenification or hyperpigmentation in associated areas. Head lice most often manifest with localized scalp pruritus and associated excoriation and cervical or occipital lymphadenopathy.32

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of pediculosis is clinical, with confirmation requiring direct examination of the insect or nits (the egg case of the parasite)(Figure 4). Body lice and associated nits can be visualized on clothing seams near areas of highest body temperature, particularly the waistband. Head lice may be visualized crawling on hair shafts or on a louse comb. Nits are firmly attached to hair shafts and are visible to the naked eye, whereas pseudonits slide freely along the hair shaft and are not a manifestation of louse infestation (Figure 5).31

Treatment—Treatment varies by affected area. Pediculosis corporis may be treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the entire body and left on for 8 to 10 hours, but this may not be necessary if facilities are available to wash and dry clothing.33 The use of oral ivermectin and permethrin-impregnated underwear both have been proposed.34,35 Treatment of pediculosis capitis may be accomplished with a variety of topical pediculicides including permethrin, pyrethrum with piperonyl butoxide, dimethicone, malathion, benzyl alcohol, spinosad, and topical ivermectin.22 Topical corticosteroids or emollients may be employed for residual pruritus.

Equally important is environmental elimination of infestation. Clothing should be discarded if possible or washed and dried using high heat. If neither approach is possible or appropriate, clothing may be sealed in a plastic bag for 2 weeks or treated with a pediculicide. Nit combing is an important adjunct in the treatment of pediculosis capitis.36 It is important to encourage return to work and/or school immediately after treatment. “No nit” policies are more harmful to education than helpful for prevention of investation.37

Pediculosis corporis may transmit infectious agents including Bartonella quintana, (trench fever, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis), Borrelia recurrentis (louse-borne relapsing fever), and Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus).31,38,39 Additionally, severe pediculosis infestations have the potential to cause chronic blood loss in affected populations. In a study of patients with active pediculosis infestation, mean hemoglobin values were found to be 2.5 g/dL lower than a matched population without infestation.40 It is important to consider pediculosis as a risk for iron-deficiency anemia in populations who are known to lack access to regular medical evaluation.41

Future Considerations

Increased access to tools and education for clinicians treating refugee populations is key to reducing the burden of parasitic skin disease and related morbidity and mortality in vulnerable groups both domestically and globally. One such tool, the Skin NTDs App, was launched by the World Health Organization in 2020. It is available for free for Android and iOS devices to assist clinicians in the field with the diagnosis and treatment of neglected tropical diseases—including scabies—that may affect refugee populations.42

Additionally, to both improve access and limit preventable sequelae, future investigations into appropriate models of community-based care are paramount. The model of community-based care is centered on the idea of care provision that prioritizes safety, accessibility, affordability, and acceptability in an environment closest to vulnerable populations. The largest dermatologic society, the International League of Dermatological Societies, formed a Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group that prioritizes understanding and improving care for refugee and migrant populations; this group hosted a summit in 2022, bringing together international subject matter leaders to discuss such models of care and set goals for the creation of tool kits for patients, frontline health care workers, and dermatologists.43

Conclusion

Improvement in dermatologic care of refugee populations includes provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate care by trained clinicians, adequate access to the most essential medications, and basic physical or legal access to health care systems in general.8,11,44 Parasitic infestations have the potential to remain asymptomatic for extended periods of time and result in spread to potentially nonendemic regions of resettlement.45 Additionally, the psychosocial well-being of refugee populations upon resettlement may be negatively affected by stigma of disease processes such as scabies and pediculosis, leading to additional barriers to successful re-entry into the patient’s new environment.46 Therefore, proper screening, diagnosis, and treatment of the most common parasitic infestations in this population have great potential to improve outcomes for large groups across the globe.

- Monin K, Batalova J, Lai T. Refugees and Asylees in the United States. Migration Information Source. Published May 13, 2021. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states-2021

- UNHCR. Figures at a Glance. UNHCR USA. Update June 14, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

- UNHCR. Refugee resettlement facts. Published October 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/refugee-resettlement-facts

- US Department of State. Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2024. Published November 3, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.state.gov/report-to-congress-on-proposed-refugee-admissions-for-fiscal-year-2024/

- UNHCR. Compact for Migration: Definitions. United Nations. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Published December 2010. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

- Kibar Öztürk M. Skin diseases in rural Nyala, Sudan (in a rural hospital, in 12 orphanages, and in two refugee camps). Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1341-1349. doi:10.1111/ijd.14619

- Padovese V, Knapp A. Challenges of managing skin diseases in refugees and migrants. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:101-115. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.08.010

- Saikal SL, Ge L, Mir A, et al. Skin disease profile of Syrian refugees in Jordan: a field-mission assessment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:419-425. doi:10.1111/jdv.15909

- Eonomopoulou A, Pavli A, Stasinopoulou P, et al. Migrant screening: lessons learned from the migrant holding level at the Greek-Turkish borders. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:177-184. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.012

- Marano N, Angelo KM, Merrill RD, et al. Expanding travel medicine in the 21st century to address the health needs of the world’s migrants.J Travel Med. 2018;25. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay067

- Hay RJ, Asiedu K. Skin-related neglected tropical diseases (skin NTDs)—a new challenge. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;4. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4010004

- NIAID. Neglected tropical diseases. Updated July 11, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/neglected-tropical-diseases

- Arlian LG, Morgan MS. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:297. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1

- Arlian LG, Runyan RA, Achar S, et al. Survival and infectivity of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis and var. hominis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):210-215. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70151-4

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Mellanby K, Johnson CG, Bartley WC. Treatment of scabies. Br Med J. 1942;2:1-4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4252.1

- Walton SF. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to scabies. Parasit Immunol. 2010;32:532-540. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01218.x

- Coates SJ, Thomas C, Chosidow O, et al. Ectoparasites: pediculosis and tungiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:551-569. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.110

- Engelman D, Fuller LC, Steer AC; International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Delphi p. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of scabies: a Delphi study of international experts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006549. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006549

- World Health Organization. WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines—23rd list, 2023. Updated July 26, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.02

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, et al. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1248-1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Badiaga S, Brouqui P. Human louse-transmitted infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:332-337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03778.x

- Leo NP, Campbell NJH, Yang X, et al. Evidence from mitochondrial DNA that head lice and body lice of humans (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) are conspecific. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:662-666. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-39.4.662

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)09458-1

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Détrez M-A, et al. Prevalences of scabies and pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112. doi:10.1111/bjd.14226

- Brouqui P. Arthropod-borne diseases associated with political and social disorder. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:357-374. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144739

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02729-4

- Bloomfield D. Head lice. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:34-35; discussion 34-35. doi:10.1542/pir.23-1-34

- Stone SP GJ, Bacelieri RE. Scabies, other mites, and pediculosis. In: Wolf K GL, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw Hill; 2008:2029.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476. doi:10.1086/499279

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6398

- CDC. Parasites: Treatment. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/treatment.html

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1355-e1365. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0746

- Ohl ME, Spach DH. Bartonella quintana and urban trench fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:131-135. doi:10.1086/313890

- Drali R, Sangaré AK, Boutellis A, et al. Bartonella quintana in body lice from scalp hair of homeless persons, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:907-908. doi:10.3201/eid2005.131242

- Rudd N, Zakaria A, Kohn MA, et al. Association of body lice infestation with hemoglobin values in hospitalized dermatology patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:691-693. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0818

- Guss DA, Koenig M, Castillo EM. Severe iron deficiency anemia and lice infestation. J Emergency Med. 2011;41:362-365. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.030

- Neglected tropical diseases of the skin: WHO launches mobile application to facilitate diagnosis. News release. World Health Organization; July 16, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/16-07-2020-neglected-tropical-diseases-of-the-skin-who-launches-mobile-application-to-facilitate-diagnosis

- Padovese V, Fuller LC, Griffiths CEM, et al; Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group of the International Foundation for Dermatology. Migrant skin health: perspectives from the Migrant Health Summit, Malta, 2022. Br J Dermatology. 2023;188:553-554. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad001

- Knapp AP, Rehmus W, Chang AY. Skin diseases in displaced populations: a review of contributing factors, challenges, and approaches to care. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1299-1311. doi:10.1111/ijd.15063

- Norman FF, Comeche B, Chamorro S, et al. Overcoming challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of parasitic infectious diseases in migrants. Expert Rev Anti-infective Therapy. 2020;18:127-143. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1713099

- Skin NTDs: prioritizing integrated approaches to reduce suffering, psychosocial impact and stigmatization. News release. World Health Organization; October 29, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2020-skin-ntds-prioritizing-integrated-approaches-to-reduce-suffering-psychosocial-impact-and-stigmatization

- Monin K, Batalova J, Lai T. Refugees and Asylees in the United States. Migration Information Source. Published May 13, 2021. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states-2021

- UNHCR. Figures at a Glance. UNHCR USA. Update June 14, 2023. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

- UNHCR. Refugee resettlement facts. Published October 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/refugee-resettlement-facts

- US Department of State. Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2024. Published November 3, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.state.gov/report-to-congress-on-proposed-refugee-admissions-for-fiscal-year-2024/

- UNHCR. Compact for Migration: Definitions. United Nations. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Published December 2010. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

- Kibar Öztürk M. Skin diseases in rural Nyala, Sudan (in a rural hospital, in 12 orphanages, and in two refugee camps). Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1341-1349. doi:10.1111/ijd.14619

- Padovese V, Knapp A. Challenges of managing skin diseases in refugees and migrants. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:101-115. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.08.010

- Saikal SL, Ge L, Mir A, et al. Skin disease profile of Syrian refugees in Jordan: a field-mission assessment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:419-425. doi:10.1111/jdv.15909

- Eonomopoulou A, Pavli A, Stasinopoulou P, et al. Migrant screening: lessons learned from the migrant holding level at the Greek-Turkish borders. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:177-184. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.012

- Marano N, Angelo KM, Merrill RD, et al. Expanding travel medicine in the 21st century to address the health needs of the world’s migrants.J Travel Med. 2018;25. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay067

- Hay RJ, Asiedu K. Skin-related neglected tropical diseases (skin NTDs)—a new challenge. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;4. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4010004

- NIAID. Neglected tropical diseases. Updated July 11, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/neglected-tropical-diseases

- Arlian LG, Morgan MS. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:297. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1

- Arlian LG, Runyan RA, Achar S, et al. Survival and infectivity of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis and var. hominis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 pt 1):210-215. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70151-4

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, et al. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:960-967. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Mellanby K, Johnson CG, Bartley WC. Treatment of scabies. Br Med J. 1942;2:1-4. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4252.1

- Walton SF. The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to scabies. Parasit Immunol. 2010;32:532-540. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01218.x

- Coates SJ, Thomas C, Chosidow O, et al. Ectoparasites: pediculosis and tungiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:551-569. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.110

- Engelman D, Fuller LC, Steer AC; International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Delphi p. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of scabies: a Delphi study of international experts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0006549. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006549

- World Health Organization. WHO Model Lists of Essential Medicines—23rd list, 2023. Updated July 26, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.02

- Salavastru CM, Chosidow O, Boffa MJ, et al. European guideline for the management of scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1248-1253. doi:10.1111/jdv.14351

- Badiaga S, Brouqui P. Human louse-transmitted infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:332-337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03778.x

- Leo NP, Campbell NJH, Yang X, et al. Evidence from mitochondrial DNA that head lice and body lice of humans (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) are conspecific. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:662-666. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-39.4.662

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)09458-1

- Arnaud A, Chosidow O, Détrez M-A, et al. Prevalences of scabies and pediculosis corporis among homeless people in the Paris region: results from two randomized cross-sectional surveys (HYTPEAC study). Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:104-112. doi:10.1111/bjd.14226

- Brouqui P. Arthropod-borne diseases associated with political and social disorder. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:357-374. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144739

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02729-4

- Bloomfield D. Head lice. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:34-35; discussion 34-35. doi:10.1542/pir.23-1-34

- Stone SP GJ, Bacelieri RE. Scabies, other mites, and pediculosis. In: Wolf K GL, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw Hill; 2008:2029.

- Foucault C, Ranque S, Badiaga S, et al. Oral ivermectin in the treatment of body lice. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:474-476. doi:10.1086/499279

- Benkouiten S, Drali R, Badiaga S, et al. Effect of permethrin-impregnated underwear on body lice in sheltered homeless persons: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:273-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6398

- CDC. Parasites: Treatment. Updated October 15, 2019. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/treatment.html

- Devore CD, Schutze GE; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1355-e1365. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0746

- Ohl ME, Spach DH. Bartonella quintana and urban trench fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:131-135. doi:10.1086/313890

- Drali R, Sangaré AK, Boutellis A, et al. Bartonella quintana in body lice from scalp hair of homeless persons, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:907-908. doi:10.3201/eid2005.131242

- Rudd N, Zakaria A, Kohn MA, et al. Association of body lice infestation with hemoglobin values in hospitalized dermatology patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:691-693. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0818

- Guss DA, Koenig M, Castillo EM. Severe iron deficiency anemia and lice infestation. J Emergency Med. 2011;41:362-365. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.030

- Neglected tropical diseases of the skin: WHO launches mobile application to facilitate diagnosis. News release. World Health Organization; July 16, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/16-07-2020-neglected-tropical-diseases-of-the-skin-who-launches-mobile-application-to-facilitate-diagnosis

- Padovese V, Fuller LC, Griffiths CEM, et al; Migrant Health Dermatology Working Group of the International Foundation for Dermatology. Migrant skin health: perspectives from the Migrant Health Summit, Malta, 2022. Br J Dermatology. 2023;188:553-554. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad001

- Knapp AP, Rehmus W, Chang AY. Skin diseases in displaced populations: a review of contributing factors, challenges, and approaches to care. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1299-1311. doi:10.1111/ijd.15063

- Norman FF, Comeche B, Chamorro S, et al. Overcoming challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of parasitic infectious diseases in migrants. Expert Rev Anti-infective Therapy. 2020;18:127-143. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1713099

- Skin NTDs: prioritizing integrated approaches to reduce suffering, psychosocial impact and stigmatization. News release. World Health Organization; October 29, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2020-skin-ntds-prioritizing-integrated-approaches-to-reduce-suffering-psychosocial-impact-and-stigmatization

Practice Points

- War and natural disasters displace populations and disrupt infrastructure and access to medical care.

- Infestations and cutaneous infections are common among refugee populations, and impetigo often is a sign of underlying scabies infestation.

- Body lice are important disease vectors inrefugee populations.