User login

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

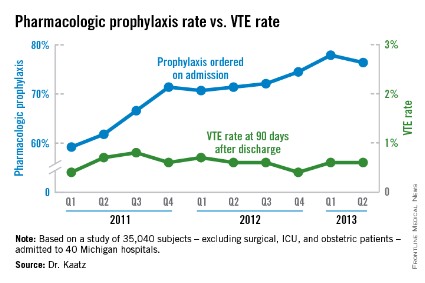

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Major finding: As VTE prophylaxis climbed from 59.2% to 77.9% over 2-plus years, the rate of symptomatic VTEs held steady at 0.56%, but major bleeds associated with prophylaxis increased from 0.2% to 0.6%.

Data Source: Observational studies involving tens of thousands of nonsurgical, non-ICU adult inpatients in Michigan hospitals.

Disclosures: The work was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. A principal investigator reports ties to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer-Bristol-Myers Squibb.