User login

Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM): Hospital Medicine 2014 (SHM Annual Meeting)

Despite VTE prophylaxis, more bleeds, no benefit in medical inpatients

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

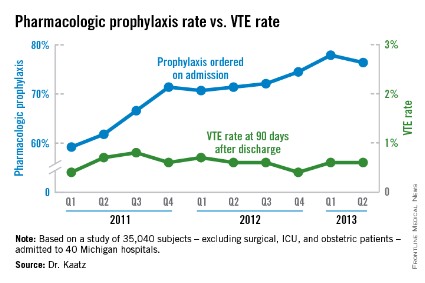

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

It may be worth looking again at prophylaxis in the general medical inpatient who’s at low risk for VTE, and who’s going to be in the hospital for a short period of time. It’s been generally believed that hospitalized patients are at moderate risk, but as we are getting more data like these, we are realizing that there may be a population of hospitalized patients who are at lower risk than we thought. That raises a question: Do they really need prophylaxis?

In general, we need to be more thoughtful about VTE prophylaxis. It costs money, and may have adverse outcomes.

Dr. Eduard E. Vasilevskis is a hospitalist and is in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He has no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis does not seem to prevent symptomatic deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in nonsurgical, non-ICU hospital patients, but it does seem to increase the risk of major bleeding, according to a series of large, observational studies from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium, a quality improvement program involving 40 Michigan hospitals.

Spurred by the Joint Commission and others, hospitalists across the United States have "put their foot on the gas to increase pharmacologic prophylaxis, and we’re using it in patients we think really should get it, but also in some patients who probably shouldn’t. We need more research to" distinguish between the two groups. "Many of us feel that the pendulum has swung too far, and that we need to bring it back to the middle," said investigator Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer and leader of the hospitalist program at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich.

Among the Consortium’s findings, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis – generally a subcutaneous shot with a heparin product – was ordered at admission for 59.2% of general adult inpatients in the first quarter of 2011, excluding surgical, ICU, and obstetric patients. By the second quarter of 2013, that had risen to 76.4%. Even so, among the 35,040 subjects included in the analysis, the rate of symptomatic VTEs averaged 0.56% throughout the observation period, and did not decrease as more patients were prophylaxed (P for trend = .114). The investigators followed their subjects in the hospital, and for 3 months afterward.

"We have not shown a good correlation between increasing prophylaxis and decreasing hospital-associated VTE," Dr. Kaatz said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Meanwhile, in a second analysis of 26,205 prophylaxed medical inpatients, the rates of major bleeding tripled from 0.2% to 0.6% over the 2-plus years that prophylaxis was becoming more common (P = .052). Prophylaxis rates also climbed from 8.7% to 25.8% among a subset of 1,165 patients contraindicated because of their bleeding risks. The relationship between contraindications and the increased bleeding rate isn’t clear; some who bled had contraindications, but others did not.

"Five years ago, I was an advocate: prophylaxis everybody. [Now,] I’m really worried that I might be causing some bleeding. VTE rates are pretty low," and lower than once thought among general medical inpatients, may be caused by early mobilization and shorter hospital stays. "We are really spending a lot of effort to prophylaxis something that’s" uncommon, without clear benefit and possible harm. "I think several of us will take [these findings] back to our hospitals to change our prophylaxis protocols," Dr. Kaatz said.

Consortium members came up with their own list of contraindications because "there’s not a lot of literature, unfortunately," to help, he noted. The list included brain metastases; intracranial monitoring devices; severe head or spine trauma within 24 hours; gastrointestinal, genitourinary or other hemorrhages within 6 months; intracranial hemorrhage within a year; and platelet counts below 50,000/mm3.

The Caprini score is one of several proposed to distinguish high-risk VTE patients from others, but in a third study, investigators found that it "did not effectively discriminate populations for which pharmacologic prophylaxis was useful." Scores of 5 or higher did predict risk, but among high-scorers, 0.72% who received prophylaxis – and 0.86% who did not – developed VTEs, an insignificant difference (P = .26). Michigan researchers have found other scoring systems to be problematic, as well.

"The mantra for years now has been to prophylaxis for VTEs, so a lot of us are treating to prophylaxis everybody," even low Caprini-score patients. "Now, we’re taking a step back. There’s a movement toward weighing VTE and bleeding risks. If we can find the population that doesn’t warrant prophylaxis, that would be a big step," said investigator Dr. Paul Grant, a hospitalist who is with the internal medicine department at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The consortium is funded by Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. Dr. Grant has no disclosures. Dr. Kaatz is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Major finding: As VTE prophylaxis climbed from 59.2% to 77.9% over 2-plus years, the rate of symptomatic VTEs held steady at 0.56%, but major bleeds associated with prophylaxis increased from 0.2% to 0.6%.

Data Source: Observational studies involving tens of thousands of nonsurgical, non-ICU adult inpatients in Michigan hospitals.

Disclosures: The work was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Blue Care Network. A principal investigator reports ties to Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Pfizer-Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Start rapid status epilepticus protocol when convulsions go past 2 minutes

LAS VEGAS – The treatment window for generalized, convulsive status epilepticus has been compressed in recent years, something that’s important for hospitalists to know, according to Dr. Andrew Josephson, medical director of inpatient neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

"We’ve figured out that, for every minute that goes by, brain cells are dying and the seizure is becoming more resistant to treatment," he said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Previously, general anesthetics didn’t come into play for maybe an hour or more. "That’s not how we do it nowadays. If a spell goes on for longer than 2 minutes, that’s status epilepticus and should be treated as such," he said.

Lorazepam 2 mg IV comes first, every 2 minutes "until you’re worried about their airway" – generally after 4-8 doses. If lorazepam doses don’t work, patients are "loaded with IV fosphenytoin," not phenytoin, which is limb threatening if it infiltrates from the peripheral intravenous line. The dose of fosphenytoin is 18-20 mg/kg; a gram is insufficient in most adults, Dr. Josephson said.

Fosphenytoin takes about 10 minutes to run in. If patients are still seizing, "we generally go right to intubation, putting the patient in a suppressive state with general anesthetics. The things that we use are IV midazolam or IV propofol," he said.

"Keep in mind, we generally paralyze someone to intubate them, so they will stop shaking. That does not mean they have stopped seizing. So at this point, it’s extremely important that EEGs are taken when the patient is under general anesthesia," he said.

Follow-up in the hospital depends on whether it’s the patient’s first seizure or if he or she is a known epileptic.

Most first-time seizures in adults have an obvious explanation. Drugs and alcohol are high on the differential, along with meningitis/encephalitis. If the attack started focally, the patient has a brain tumor until proven otherwise. Low glucose also could be to blame, or low sodium, low magnesium, or low or high calcium.

Breakthrough seizures in known epileptics generally mean that something’s wrong with their antiepileptic medications – either they aren’t taking them or a new drug is interfering with them – or that they have a urinary tract infection, pneumonia, or some other systemic infection, and not necessarily a CNS infection.

Intramuscular midazolam has been in the news recently after it was found in a trial that 10 mg delivered by paramedics to the thigh by auto-injector works at least as well as intravenous lorazepam for status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600). Approval might come in 2014, and when it does the auto-injector is likely to "become the standard of care and benzodiazepine of choice for status epilepticus outside of the hospital and probably inside the hospital" since it’s far less cumbersome than fumbling with intravenous lines in the middle of a neurologic emergency, Dr. Josephson said.

Dr. Josephson has no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – The treatment window for generalized, convulsive status epilepticus has been compressed in recent years, something that’s important for hospitalists to know, according to Dr. Andrew Josephson, medical director of inpatient neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

"We’ve figured out that, for every minute that goes by, brain cells are dying and the seizure is becoming more resistant to treatment," he said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Previously, general anesthetics didn’t come into play for maybe an hour or more. "That’s not how we do it nowadays. If a spell goes on for longer than 2 minutes, that’s status epilepticus and should be treated as such," he said.

Lorazepam 2 mg IV comes first, every 2 minutes "until you’re worried about their airway" – generally after 4-8 doses. If lorazepam doses don’t work, patients are "loaded with IV fosphenytoin," not phenytoin, which is limb threatening if it infiltrates from the peripheral intravenous line. The dose of fosphenytoin is 18-20 mg/kg; a gram is insufficient in most adults, Dr. Josephson said.

Fosphenytoin takes about 10 minutes to run in. If patients are still seizing, "we generally go right to intubation, putting the patient in a suppressive state with general anesthetics. The things that we use are IV midazolam or IV propofol," he said.

"Keep in mind, we generally paralyze someone to intubate them, so they will stop shaking. That does not mean they have stopped seizing. So at this point, it’s extremely important that EEGs are taken when the patient is under general anesthesia," he said.

Follow-up in the hospital depends on whether it’s the patient’s first seizure or if he or she is a known epileptic.

Most first-time seizures in adults have an obvious explanation. Drugs and alcohol are high on the differential, along with meningitis/encephalitis. If the attack started focally, the patient has a brain tumor until proven otherwise. Low glucose also could be to blame, or low sodium, low magnesium, or low or high calcium.

Breakthrough seizures in known epileptics generally mean that something’s wrong with their antiepileptic medications – either they aren’t taking them or a new drug is interfering with them – or that they have a urinary tract infection, pneumonia, or some other systemic infection, and not necessarily a CNS infection.

Intramuscular midazolam has been in the news recently after it was found in a trial that 10 mg delivered by paramedics to the thigh by auto-injector works at least as well as intravenous lorazepam for status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600). Approval might come in 2014, and when it does the auto-injector is likely to "become the standard of care and benzodiazepine of choice for status epilepticus outside of the hospital and probably inside the hospital" since it’s far less cumbersome than fumbling with intravenous lines in the middle of a neurologic emergency, Dr. Josephson said.

Dr. Josephson has no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – The treatment window for generalized, convulsive status epilepticus has been compressed in recent years, something that’s important for hospitalists to know, according to Dr. Andrew Josephson, medical director of inpatient neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

"We’ve figured out that, for every minute that goes by, brain cells are dying and the seizure is becoming more resistant to treatment," he said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Previously, general anesthetics didn’t come into play for maybe an hour or more. "That’s not how we do it nowadays. If a spell goes on for longer than 2 minutes, that’s status epilepticus and should be treated as such," he said.

Lorazepam 2 mg IV comes first, every 2 minutes "until you’re worried about their airway" – generally after 4-8 doses. If lorazepam doses don’t work, patients are "loaded with IV fosphenytoin," not phenytoin, which is limb threatening if it infiltrates from the peripheral intravenous line. The dose of fosphenytoin is 18-20 mg/kg; a gram is insufficient in most adults, Dr. Josephson said.

Fosphenytoin takes about 10 minutes to run in. If patients are still seizing, "we generally go right to intubation, putting the patient in a suppressive state with general anesthetics. The things that we use are IV midazolam or IV propofol," he said.

"Keep in mind, we generally paralyze someone to intubate them, so they will stop shaking. That does not mean they have stopped seizing. So at this point, it’s extremely important that EEGs are taken when the patient is under general anesthesia," he said.

Follow-up in the hospital depends on whether it’s the patient’s first seizure or if he or she is a known epileptic.

Most first-time seizures in adults have an obvious explanation. Drugs and alcohol are high on the differential, along with meningitis/encephalitis. If the attack started focally, the patient has a brain tumor until proven otherwise. Low glucose also could be to blame, or low sodium, low magnesium, or low or high calcium.

Breakthrough seizures in known epileptics generally mean that something’s wrong with their antiepileptic medications – either they aren’t taking them or a new drug is interfering with them – or that they have a urinary tract infection, pneumonia, or some other systemic infection, and not necessarily a CNS infection.

Intramuscular midazolam has been in the news recently after it was found in a trial that 10 mg delivered by paramedics to the thigh by auto-injector works at least as well as intravenous lorazepam for status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600). Approval might come in 2014, and when it does the auto-injector is likely to "become the standard of care and benzodiazepine of choice for status epilepticus outside of the hospital and probably inside the hospital" since it’s far less cumbersome than fumbling with intravenous lines in the middle of a neurologic emergency, Dr. Josephson said.

Dr. Josephson has no relevant disclosures.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 14

VIDEO: Feeding elderly patients after hip surgery

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Among 100 hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital, those fed within 24 hours left the hospital sooner, and fewer of them died. Other patients went up to a week without being fed.

Doctors might have overlooked nutrition or been put off by the notion that gastronomy feeding tubes don’t help in end-stage dementia. The Salem patients, however, didn’t have end-stage dementia and were being fed by nasogastric tubes. In an interview, Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in nearby Portland, explained that it’s time to broaden who’s authorized to order nutritional consults, so that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Plasma fluoride levels tied to voriconazole-induced periostitis

LAS VEGAS – Check fluoride levels in patients on long-term voriconazole who present with new-onset bone pain, researchers at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich., advised after a retrospective investigation of 28 patients who were on the antifungal for a couple of months.

Plasma fluoride levels above 8 micromol/L are 95% sensitive (95% CI, 0.76-0.99) and 100% specific (95% CI, 0.59-1.0) for periostitis triggered by the fluorine atoms in the voriconazole molecule. Stopping the antifungal – or switching to one that does not contain fluorine, like itraconazole – is likely to clear the bone pain in a few weeks or months.

If bone scans can’t be ordered – or are too expensive – in voriconazole patients with skeletal pain, "getting a fluoride level is worthwhile. It’s much cheaper, and is very predictive" for voriconazole periostitis, said lead investigator Dr. Woo Moon of St. Joseph’s.

"One hundred percent of the patients who had periostitis had either involvement of the rib or ulna, and both in almost half of the cases," he said, noting that this is puzzling because previous reports of fluoride periostitis have been in the lower extremities.

The findings come in the wake of CNS fungal infections and abscesses caused by contaminated methylprednisolone injections in 2012 and 2013; 195 patients were treated at the hospital with voriconazole, as suggested by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention because of the drug’s superior CNS penetration and activity against suspected pathogens.

Up to 59 patients (30%) reported pain in the ribs and arms after a couple months of treatment. The current investigation involved the 28 adult patients who had both fluoride level measurements and full-body scans to check for periostitis.

Plasma fluoride levels were significantly higher in the 21 (75%) who turned out to have periostitis (12.78 vs. 3.61 micromol/L, P less than .001). They were also on significantly higher doses of voriconazole (780 vs. 450 mg/day; P less than .001) and had significantly higher serum alkaline phosphatase levels (273 vs. 117 IU/L; P = .02). There were no differences in alanine transaminase, bilirubin, or creatinine levels.

Pain "improved dramatically" from 2 weeks to 5 months after discontinuation in 17 of the 19 (89%) patients who had pain outcomes noted in their records. Pain did not improve in the two others, Dr. Moon said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Each molecule of voriconazole contains three fluorine atoms. At the recommended maintenance dose of 200 mg twice daily, "you’re taking in 65 mg of fluoride per day, 15 times the United States Department of Agriculture’s daily allowance," he said.

Voriconazole periostitis has been reported before in case studies and small series. However, because of the rib and ulna involvement, quick resolution after discontinuation, and strong predictive value of fluoride measurements, "we thought it was worthwhile to report our findings," he said.

Dr. Moon said she has no relevant financial disclosures, and the work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – Check fluoride levels in patients on long-term voriconazole who present with new-onset bone pain, researchers at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich., advised after a retrospective investigation of 28 patients who were on the antifungal for a couple of months.

Plasma fluoride levels above 8 micromol/L are 95% sensitive (95% CI, 0.76-0.99) and 100% specific (95% CI, 0.59-1.0) for periostitis triggered by the fluorine atoms in the voriconazole molecule. Stopping the antifungal – or switching to one that does not contain fluorine, like itraconazole – is likely to clear the bone pain in a few weeks or months.

If bone scans can’t be ordered – or are too expensive – in voriconazole patients with skeletal pain, "getting a fluoride level is worthwhile. It’s much cheaper, and is very predictive" for voriconazole periostitis, said lead investigator Dr. Woo Moon of St. Joseph’s.

"One hundred percent of the patients who had periostitis had either involvement of the rib or ulna, and both in almost half of the cases," he said, noting that this is puzzling because previous reports of fluoride periostitis have been in the lower extremities.

The findings come in the wake of CNS fungal infections and abscesses caused by contaminated methylprednisolone injections in 2012 and 2013; 195 patients were treated at the hospital with voriconazole, as suggested by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention because of the drug’s superior CNS penetration and activity against suspected pathogens.

Up to 59 patients (30%) reported pain in the ribs and arms after a couple months of treatment. The current investigation involved the 28 adult patients who had both fluoride level measurements and full-body scans to check for periostitis.

Plasma fluoride levels were significantly higher in the 21 (75%) who turned out to have periostitis (12.78 vs. 3.61 micromol/L, P less than .001). They were also on significantly higher doses of voriconazole (780 vs. 450 mg/day; P less than .001) and had significantly higher serum alkaline phosphatase levels (273 vs. 117 IU/L; P = .02). There were no differences in alanine transaminase, bilirubin, or creatinine levels.

Pain "improved dramatically" from 2 weeks to 5 months after discontinuation in 17 of the 19 (89%) patients who had pain outcomes noted in their records. Pain did not improve in the two others, Dr. Moon said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Each molecule of voriconazole contains three fluorine atoms. At the recommended maintenance dose of 200 mg twice daily, "you’re taking in 65 mg of fluoride per day, 15 times the United States Department of Agriculture’s daily allowance," he said.

Voriconazole periostitis has been reported before in case studies and small series. However, because of the rib and ulna involvement, quick resolution after discontinuation, and strong predictive value of fluoride measurements, "we thought it was worthwhile to report our findings," he said.

Dr. Moon said she has no relevant financial disclosures, and the work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – Check fluoride levels in patients on long-term voriconazole who present with new-onset bone pain, researchers at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor, Mich., advised after a retrospective investigation of 28 patients who were on the antifungal for a couple of months.

Plasma fluoride levels above 8 micromol/L are 95% sensitive (95% CI, 0.76-0.99) and 100% specific (95% CI, 0.59-1.0) for periostitis triggered by the fluorine atoms in the voriconazole molecule. Stopping the antifungal – or switching to one that does not contain fluorine, like itraconazole – is likely to clear the bone pain in a few weeks or months.

If bone scans can’t be ordered – or are too expensive – in voriconazole patients with skeletal pain, "getting a fluoride level is worthwhile. It’s much cheaper, and is very predictive" for voriconazole periostitis, said lead investigator Dr. Woo Moon of St. Joseph’s.

"One hundred percent of the patients who had periostitis had either involvement of the rib or ulna, and both in almost half of the cases," he said, noting that this is puzzling because previous reports of fluoride periostitis have been in the lower extremities.

The findings come in the wake of CNS fungal infections and abscesses caused by contaminated methylprednisolone injections in 2012 and 2013; 195 patients were treated at the hospital with voriconazole, as suggested by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention because of the drug’s superior CNS penetration and activity against suspected pathogens.

Up to 59 patients (30%) reported pain in the ribs and arms after a couple months of treatment. The current investigation involved the 28 adult patients who had both fluoride level measurements and full-body scans to check for periostitis.

Plasma fluoride levels were significantly higher in the 21 (75%) who turned out to have periostitis (12.78 vs. 3.61 micromol/L, P less than .001). They were also on significantly higher doses of voriconazole (780 vs. 450 mg/day; P less than .001) and had significantly higher serum alkaline phosphatase levels (273 vs. 117 IU/L; P = .02). There were no differences in alanine transaminase, bilirubin, or creatinine levels.

Pain "improved dramatically" from 2 weeks to 5 months after discontinuation in 17 of the 19 (89%) patients who had pain outcomes noted in their records. Pain did not improve in the two others, Dr. Moon said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Each molecule of voriconazole contains three fluorine atoms. At the recommended maintenance dose of 200 mg twice daily, "you’re taking in 65 mg of fluoride per day, 15 times the United States Department of Agriculture’s daily allowance," he said.

Voriconazole periostitis has been reported before in case studies and small series. However, because of the rib and ulna involvement, quick resolution after discontinuation, and strong predictive value of fluoride measurements, "we thought it was worthwhile to report our findings," he said.

Dr. Moon said she has no relevant financial disclosures, and the work received no outside funding.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Major finding: Plasma fluoride levels above 8 micromol/L are 95% sensitive (95% CI 0.76-0.99) and 100% specific (95% CI 0.59-1.0) for periostitis triggered by the fluorine atoms in voriconazole.

Data Source: A retrospective investigation of 28 adult patients who developed bone pain after a couple months on the antifungal.

Disclosures: The lead investigator said she has no relevant financial disclosures, and the work received no outside funding.

VIDEO: Rethink the VTE prophylaxis mantra

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

LAS VEGAS – Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis – a sine qua non of the Joint Commission and others – doesn’t seem to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in hospitalized medical patients, but it does make them more likely to bleed, according to investigators from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety Consortium.

The findings are prompting one of those investigators to reassess his own approach. In an interview at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s 2014 meeting, Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich., told us how he’s thinking a bit differently these days when it comes to VTE prophylaxis in medical inpatients.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Early tube feeding may speed discharge for elderly hip fracture patients

LAS VEGAS – Lengths of hospital stay were nearly halved in elderly hip fracture patients started on enteral nutrition within 24 hours of surgery, according to a retrospective cohort study of 100 sequential hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital.

The 89 patients fed by nasogastric tube within 24 hours stayed in the hospital an average of 4.43 days. The 11 fed an average of 4.36 days later stayed an average of 7.80 days.

The risk of hospital stays 5 days or longer quadrupled when enteral nutrition was delayed (RR, 4.14). Two patients (18%) died in the delayed-feeding group; eight (9%) died in the early-feeding group.

The average age in the study was 83 years old. Patients who went for more than a day without being fed – the range was 2-7 days – were a bit older with an average age of 86 years, "meaning that they were unlikely to have much in the way of reserves and were very likely to have some malnutrition at baseline," said Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in Portland, Ore., as well as a palliative care consultant at Salem Hospital.

"Association doesn’t prove causality," she said. It’s possible that those who went longer without nutrition were sicker and more confused.

Even so, "the correlation was pretty compelling." The findings argue strongly for early nutrition "whether or not it’s known absolutely" that it improves outcomes. Nutrition is essential for recovery: "If you are going to treat a patient aggressively, you need to give them nutrition. It’s just the right thing to do." It may also save a lot of money. A day in the hospital costs more than $4,000, while feedings cost about $35 a day, Dr. Wallace said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

"Given an ALOS [average length of stay] of 7 days without intervention, an early 3-day trial of enteral nutrition could save the hospital between $2,939 and $12,065 for an ALOS reduction of 1-4 days, respectively," she reported in the accompanying abstract. "Assuming a utility of 100%, the cost per outpatient day gained for the patient varies from $25 to $100 for a range of 4 to 1 days gained. If early enteral nutrition is responsible for the reduction in ALOS, less than 10% of 1 cent is spent to garner $1 in reduced inpatient costs."

Days go by

It’s not uncommon for elderly patients to go days without being fed. One of the reasons, Dr. Wallace said, is because there’s been an overextrapolation from studies showing that percutaneous gastrostomy tubes don’t improve quality of life or survival in end-stage dementia.

Those findings "have unintentionally influenced use of temporary feeding tubes in patients with acute issues who are otherwise receiving full medical treatment" and have resulted "in inappropriate withholding of enteral nutrition" in the elderly, she said.

"We’ve morphed the data into saying, ‘Oh, if I’ve got a patient who has some underlying dementia, I shouldn’t give them tube feeds. But the data about not doing [gastrostomy] tubes in advanced dementia has to do with people who are not undergoing acute medical treatment. That’s a very different situation from hip fractures and other acute problems in the elderly. Unfortunately, the evidence for one situation has been transposed onto a different situation, so a lot of hospitalists hesitate to initiate tube feeds," she said.

In patients who waited more than a day to get fed, "there was a lag time to even getting a nutrition consult. Nobody really quite noticed that they weren’t getting nutrition." That’s consistent "with what I’ve seen throughout my hospitalist career, and not just in hip fractures. As hospitalist doctors, we get very worked up about the medical issues, and we simply don’t attend to nutrition. We sometimes think somebody else is taking care of it," she said.

"The ages were [statistically] the same between the two groups, and there was a pretty [even] distribution of comorbidities," she noted.

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures. The work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – Lengths of hospital stay were nearly halved in elderly hip fracture patients started on enteral nutrition within 24 hours of surgery, according to a retrospective cohort study of 100 sequential hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital.

The 89 patients fed by nasogastric tube within 24 hours stayed in the hospital an average of 4.43 days. The 11 fed an average of 4.36 days later stayed an average of 7.80 days.

The risk of hospital stays 5 days or longer quadrupled when enteral nutrition was delayed (RR, 4.14). Two patients (18%) died in the delayed-feeding group; eight (9%) died in the early-feeding group.

The average age in the study was 83 years old. Patients who went for more than a day without being fed – the range was 2-7 days – were a bit older with an average age of 86 years, "meaning that they were unlikely to have much in the way of reserves and were very likely to have some malnutrition at baseline," said Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in Portland, Ore., as well as a palliative care consultant at Salem Hospital.

"Association doesn’t prove causality," she said. It’s possible that those who went longer without nutrition were sicker and more confused.

Even so, "the correlation was pretty compelling." The findings argue strongly for early nutrition "whether or not it’s known absolutely" that it improves outcomes. Nutrition is essential for recovery: "If you are going to treat a patient aggressively, you need to give them nutrition. It’s just the right thing to do." It may also save a lot of money. A day in the hospital costs more than $4,000, while feedings cost about $35 a day, Dr. Wallace said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

"Given an ALOS [average length of stay] of 7 days without intervention, an early 3-day trial of enteral nutrition could save the hospital between $2,939 and $12,065 for an ALOS reduction of 1-4 days, respectively," she reported in the accompanying abstract. "Assuming a utility of 100%, the cost per outpatient day gained for the patient varies from $25 to $100 for a range of 4 to 1 days gained. If early enteral nutrition is responsible for the reduction in ALOS, less than 10% of 1 cent is spent to garner $1 in reduced inpatient costs."

Days go by

It’s not uncommon for elderly patients to go days without being fed. One of the reasons, Dr. Wallace said, is because there’s been an overextrapolation from studies showing that percutaneous gastrostomy tubes don’t improve quality of life or survival in end-stage dementia.

Those findings "have unintentionally influenced use of temporary feeding tubes in patients with acute issues who are otherwise receiving full medical treatment" and have resulted "in inappropriate withholding of enteral nutrition" in the elderly, she said.

"We’ve morphed the data into saying, ‘Oh, if I’ve got a patient who has some underlying dementia, I shouldn’t give them tube feeds. But the data about not doing [gastrostomy] tubes in advanced dementia has to do with people who are not undergoing acute medical treatment. That’s a very different situation from hip fractures and other acute problems in the elderly. Unfortunately, the evidence for one situation has been transposed onto a different situation, so a lot of hospitalists hesitate to initiate tube feeds," she said.

In patients who waited more than a day to get fed, "there was a lag time to even getting a nutrition consult. Nobody really quite noticed that they weren’t getting nutrition." That’s consistent "with what I’ve seen throughout my hospitalist career, and not just in hip fractures. As hospitalist doctors, we get very worked up about the medical issues, and we simply don’t attend to nutrition. We sometimes think somebody else is taking care of it," she said.

"The ages were [statistically] the same between the two groups, and there was a pretty [even] distribution of comorbidities," she noted.

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures. The work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – Lengths of hospital stay were nearly halved in elderly hip fracture patients started on enteral nutrition within 24 hours of surgery, according to a retrospective cohort study of 100 sequential hip fracture patients at Salem (Ore.) Hospital.

The 89 patients fed by nasogastric tube within 24 hours stayed in the hospital an average of 4.43 days. The 11 fed an average of 4.36 days later stayed an average of 7.80 days.

The risk of hospital stays 5 days or longer quadrupled when enteral nutrition was delayed (RR, 4.14). Two patients (18%) died in the delayed-feeding group; eight (9%) died in the early-feeding group.

The average age in the study was 83 years old. Patients who went for more than a day without being fed – the range was 2-7 days – were a bit older with an average age of 86 years, "meaning that they were unlikely to have much in the way of reserves and were very likely to have some malnutrition at baseline," said Dr. Cynthia Wallace, medical director of Vibra Specialty Hospital in Portland, Ore., as well as a palliative care consultant at Salem Hospital.

"Association doesn’t prove causality," she said. It’s possible that those who went longer without nutrition were sicker and more confused.

Even so, "the correlation was pretty compelling." The findings argue strongly for early nutrition "whether or not it’s known absolutely" that it improves outcomes. Nutrition is essential for recovery: "If you are going to treat a patient aggressively, you need to give them nutrition. It’s just the right thing to do." It may also save a lot of money. A day in the hospital costs more than $4,000, while feedings cost about $35 a day, Dr. Wallace said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

"Given an ALOS [average length of stay] of 7 days without intervention, an early 3-day trial of enteral nutrition could save the hospital between $2,939 and $12,065 for an ALOS reduction of 1-4 days, respectively," she reported in the accompanying abstract. "Assuming a utility of 100%, the cost per outpatient day gained for the patient varies from $25 to $100 for a range of 4 to 1 days gained. If early enteral nutrition is responsible for the reduction in ALOS, less than 10% of 1 cent is spent to garner $1 in reduced inpatient costs."

Days go by

It’s not uncommon for elderly patients to go days without being fed. One of the reasons, Dr. Wallace said, is because there’s been an overextrapolation from studies showing that percutaneous gastrostomy tubes don’t improve quality of life or survival in end-stage dementia.

Those findings "have unintentionally influenced use of temporary feeding tubes in patients with acute issues who are otherwise receiving full medical treatment" and have resulted "in inappropriate withholding of enteral nutrition" in the elderly, she said.

"We’ve morphed the data into saying, ‘Oh, if I’ve got a patient who has some underlying dementia, I shouldn’t give them tube feeds. But the data about not doing [gastrostomy] tubes in advanced dementia has to do with people who are not undergoing acute medical treatment. That’s a very different situation from hip fractures and other acute problems in the elderly. Unfortunately, the evidence for one situation has been transposed onto a different situation, so a lot of hospitalists hesitate to initiate tube feeds," she said.

In patients who waited more than a day to get fed, "there was a lag time to even getting a nutrition consult. Nobody really quite noticed that they weren’t getting nutrition." That’s consistent "with what I’ve seen throughout my hospitalist career, and not just in hip fractures. As hospitalist doctors, we get very worked up about the medical issues, and we simply don’t attend to nutrition. We sometimes think somebody else is taking care of it," she said.

"The ages were [statistically] the same between the two groups, and there was a pretty [even] distribution of comorbidities," she noted.

Dr. Wallace said she had no relevant financial disclosures. The work received no outside funding.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Major finding: Hospital length of stay for patients receiving enteral nutrition within 24 hours of hip surgery was 4.43 days vs 7.80 days for patients who received no enteral nutrition for more than 1 day postoperatively.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 89 elderly hip fracture patients.

Disclosures: The investigator reported having no relevant financial disclosures; no outside funding was involved in the project.

Quality gap in atrial fibrillation care significant

LAS VEGAS – About 40% of atrial fibrillation inpatients leave the hospital without a prescription for stroke prevention medications, according to a retrospective review from Northwestern University in Chicago.

Investigators there calculated the CHADS2(congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke) score of 16,106 patients discharged with atrial fibrillation diagnosed by 12-lead EKG or telemetry. Guidelines call for aspirin or anticoagulation in patients with a score of 1, and anticoagulation in patients with scores of 2-6, according to lead researcher Dr. Hiren Shah, medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Even so, 41.2% of 277 patients with a CHADS2 score of 6 and 36% of of patients with a score of 5 were discharged without a prescription to prevent stroke. Additionally, 36.8% of 1,550 with a score of 4 left the hospital without such a prescription, as did 35.9% of 3,343 patients with a score of 3, 38.8% of 4,106 of patients with a score of 2 and 40.3% of 3,457 patients with a score of 1.

Among patients who were treated, about 15% with a score of 2-6 received aspirin alone, instead of warfarin or newer anticoagulants. When anticoagulation was initiated, warfarin was the most common choice.

"These data, I think, would mirror the overall population of patients throughout the country. There’s a major quality gap in atrial fibrillation. I would urge hospitalists to start quality improvement projects to address this very important clinical issue," Dr. Shah said.

The reasons for the findings are uncertain. It’s unknown if patients were started on stroke prophylaxis after discharge. The study, comprising two years of patient data starting Nov.1, 2011, also did not assess outcomes or reasons why patients went untreated.

It could be that hospitalists didn’t have time to discuss anticoagulation with patients, or didn’t calculate CHADS2 scores. They might also have overestimated bleeding risks, although if "you’re at CHADS 5 or 6, your stroke risk is 12% and 18% per year, so unless the contraindication to anticoagulation is absolute, the risk of bleeding would have to be very high for you not to choose anticoagulation," Dr. Shah said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Hospitalists might also have thought that anticoagulation is an outpatient issue, "but we think the hospital is a nice point in time where you can capture these patients and evaluate them for this issue, then communicate their stroke risk to their primary care doctor," he said.

One of the solutions is a reminder in the electronic health record to do a CHADS score, so long as the system can recognize atrial fibrillation patients. Also, with the help of funding from the Society of Hospital Medicine, "we are going to have a mentored implementation program where we’ll go to hospitals and coach them on how to improve, similar to what we did for DVT/PE [deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism] prophylaxis," Dr. Shah said.

Atrial fibrillation, in general, "is at the point where DVT/PE was several years ago. Prophylaxis was sporadic, and then there was a big push. We think atrial fibrillation is a similar condition that will be addressed aggressively in time by all hospitals," he said.

Dr. Shah is a speaker for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the maker of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto). He is also an editorial adviser for Hospitalist News. He said his work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – About 40% of atrial fibrillation inpatients leave the hospital without a prescription for stroke prevention medications, according to a retrospective review from Northwestern University in Chicago.

Investigators there calculated the CHADS2(congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke) score of 16,106 patients discharged with atrial fibrillation diagnosed by 12-lead EKG or telemetry. Guidelines call for aspirin or anticoagulation in patients with a score of 1, and anticoagulation in patients with scores of 2-6, according to lead researcher Dr. Hiren Shah, medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Even so, 41.2% of 277 patients with a CHADS2 score of 6 and 36% of of patients with a score of 5 were discharged without a prescription to prevent stroke. Additionally, 36.8% of 1,550 with a score of 4 left the hospital without such a prescription, as did 35.9% of 3,343 patients with a score of 3, 38.8% of 4,106 of patients with a score of 2 and 40.3% of 3,457 patients with a score of 1.

Among patients who were treated, about 15% with a score of 2-6 received aspirin alone, instead of warfarin or newer anticoagulants. When anticoagulation was initiated, warfarin was the most common choice.

"These data, I think, would mirror the overall population of patients throughout the country. There’s a major quality gap in atrial fibrillation. I would urge hospitalists to start quality improvement projects to address this very important clinical issue," Dr. Shah said.

The reasons for the findings are uncertain. It’s unknown if patients were started on stroke prophylaxis after discharge. The study, comprising two years of patient data starting Nov.1, 2011, also did not assess outcomes or reasons why patients went untreated.

It could be that hospitalists didn’t have time to discuss anticoagulation with patients, or didn’t calculate CHADS2 scores. They might also have overestimated bleeding risks, although if "you’re at CHADS 5 or 6, your stroke risk is 12% and 18% per year, so unless the contraindication to anticoagulation is absolute, the risk of bleeding would have to be very high for you not to choose anticoagulation," Dr. Shah said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Hospitalists might also have thought that anticoagulation is an outpatient issue, "but we think the hospital is a nice point in time where you can capture these patients and evaluate them for this issue, then communicate their stroke risk to their primary care doctor," he said.

One of the solutions is a reminder in the electronic health record to do a CHADS score, so long as the system can recognize atrial fibrillation patients. Also, with the help of funding from the Society of Hospital Medicine, "we are going to have a mentored implementation program where we’ll go to hospitals and coach them on how to improve, similar to what we did for DVT/PE [deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism] prophylaxis," Dr. Shah said.

Atrial fibrillation, in general, "is at the point where DVT/PE was several years ago. Prophylaxis was sporadic, and then there was a big push. We think atrial fibrillation is a similar condition that will be addressed aggressively in time by all hospitals," he said.

Dr. Shah is a speaker for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the maker of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto). He is also an editorial adviser for Hospitalist News. He said his work received no outside funding.

LAS VEGAS – About 40% of atrial fibrillation inpatients leave the hospital without a prescription for stroke prevention medications, according to a retrospective review from Northwestern University in Chicago.

Investigators there calculated the CHADS2(congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke) score of 16,106 patients discharged with atrial fibrillation diagnosed by 12-lead EKG or telemetry. Guidelines call for aspirin or anticoagulation in patients with a score of 1, and anticoagulation in patients with scores of 2-6, according to lead researcher Dr. Hiren Shah, medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

Even so, 41.2% of 277 patients with a CHADS2 score of 6 and 36% of of patients with a score of 5 were discharged without a prescription to prevent stroke. Additionally, 36.8% of 1,550 with a score of 4 left the hospital without such a prescription, as did 35.9% of 3,343 patients with a score of 3, 38.8% of 4,106 of patients with a score of 2 and 40.3% of 3,457 patients with a score of 1.

Among patients who were treated, about 15% with a score of 2-6 received aspirin alone, instead of warfarin or newer anticoagulants. When anticoagulation was initiated, warfarin was the most common choice.

"These data, I think, would mirror the overall population of patients throughout the country. There’s a major quality gap in atrial fibrillation. I would urge hospitalists to start quality improvement projects to address this very important clinical issue," Dr. Shah said.

The reasons for the findings are uncertain. It’s unknown if patients were started on stroke prophylaxis after discharge. The study, comprising two years of patient data starting Nov.1, 2011, also did not assess outcomes or reasons why patients went untreated.

It could be that hospitalists didn’t have time to discuss anticoagulation with patients, or didn’t calculate CHADS2 scores. They might also have overestimated bleeding risks, although if "you’re at CHADS 5 or 6, your stroke risk is 12% and 18% per year, so unless the contraindication to anticoagulation is absolute, the risk of bleeding would have to be very high for you not to choose anticoagulation," Dr. Shah said at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting.

Hospitalists might also have thought that anticoagulation is an outpatient issue, "but we think the hospital is a nice point in time where you can capture these patients and evaluate them for this issue, then communicate their stroke risk to their primary care doctor," he said.

One of the solutions is a reminder in the electronic health record to do a CHADS score, so long as the system can recognize atrial fibrillation patients. Also, with the help of funding from the Society of Hospital Medicine, "we are going to have a mentored implementation program where we’ll go to hospitals and coach them on how to improve, similar to what we did for DVT/PE [deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism] prophylaxis," Dr. Shah said.

Atrial fibrillation, in general, "is at the point where DVT/PE was several years ago. Prophylaxis was sporadic, and then there was a big push. We think atrial fibrillation is a similar condition that will be addressed aggressively in time by all hospitals," he said.

Dr. Shah is a speaker for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the maker of the anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto). He is also an editorial adviser for Hospitalist News. He said his work received no outside funding.

AT HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2014

Major finding: A total of 36% of patients with a CHADS2 score of 5, and 41.2% with a score of 6 left the hospital without medications to prevent stroke.

Data Source: Retrospective review of more than 2 years of data for 16,000 patients hospitalized for atrial fibrillation patients

Disclosures: The lead investigator is a speaker for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, maker of rivaroxaban). He said his work received no outside funding.

Initial MARQUIS results offer lessons in med reconciliation

LAS VEGAS – Tired of getting a patient medication list that isn’t reliable? A 3-year study on medication reconciliation could offer a roadmap for improving that list and reducing potentially harmful errors.

Preliminary results from MARQUIS (the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study) indicate that hospitals are able to reduce unintentional medication discrepancies by implementing a menu of interventions ranging from training providers to take a better medication history to stationing a designated provider in the emergency department to reconcile the patient’s information with pharmacies and primary care offices. But outside forces, such as problems with an electronic health record (EHR) system, can offset those effects.

The 3-year study, which will wrap up in the next few months, is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, with $1.5 million in funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

In the first phase of the study, researchers identified evidence-based techniques for taking the best possible medication history from hospitalized patients and synthesized them into a toolkit for clinicians. The free toolkit includes how-to videos and pocket cards. The second phase of the study is the mentored implementation of the techniques at five sites: two academic medical centers, two community hospitals, and one Veterans Affairs medical center.

Initial results from two of the five sites show that training on how to take a better medication history and clarity about who should be working on reconciling the medication list can help improve medication discrepancies. But while the interventions are promising, the initial case studies show mixed results.

While one community hospital site was able to lower medication discrepancies significantly, a second community hospital site had a spike in its medication discrepancies as it underwent a problematic implementation of a new EHR system.

Eighteen minutes to win it

At the first site, a Medication Reconciliation Assistant (MRA) program was used to improve the reliability of medication lists. The MRA is stationed in the emergency department and interviews patients about their medications and then verifies that list with the pharmacy, the primary care physician, or the skilled nursing facility. That new medication list is then handed off to the admitting physician. The process usually takes about 18-20 minutes.

They MRA program is staffed by four full-time employees, all pharmacy technicians with experience in retail pharmacies, who work 8-hour shifts throughout the week.

"It doesn’t have to be a pharmacy technician," said Dr. Jason Stein, a MARQUIS coinvestigator and a professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. "But somebody needs to be spending that 18 minutes doing something that roughly looks like this."

At that first site, unintentional medication discrepancies from either history or reconciliation errors dropped from 4.5 per patient at the in the preintervention period to 3.4 per patient. And the total number of potentially harmful discrepancies was reduced from 0.25 to 0.09 per patient.

At the second site, a smaller community hospital, the quality improvement team provided training to front-line providers on medication history taking and counseling at discharge and created a new hospital policy that clarified expectations about who would perform medication reconciliation and when they would do it. And recently, they began stationing a provider in the emergency department 5 days a week to work on medication reconciliation.

But shortly after the second hospital began implementing the MARQUIS interventions, the hospital launched a new EHR system that created problems for medication reconciliation. For instance, with the paper system, the admitting physician was accountable for the initial medication history. But under the electronic system, that accountability was lost. Also, the new EHR was unable to group medications as "continued," "changed," "stopped," or "new," making it difficult to perform discharge medication counseling.

The result was that, after some initial success, unintentional medication discrepancies spiked. In the preintervention period, unintentional medication discrepancies were 2.0 per patient, but they rose to nearly 5 discrepancies per patient after the rollout of the new EHR system. They have since fallen back down to 3.8 per patient. Similarly, the total of potentially harmful discrepancies rose from 0.20 to 1.11 per patient.

The free MARQUIS toolkit is available online.

On Twitter @maryellenny

LAS VEGAS – Tired of getting a patient medication list that isn’t reliable? A 3-year study on medication reconciliation could offer a roadmap for improving that list and reducing potentially harmful errors.

Preliminary results from MARQUIS (the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study) indicate that hospitals are able to reduce unintentional medication discrepancies by implementing a menu of interventions ranging from training providers to take a better medication history to stationing a designated provider in the emergency department to reconcile the patient’s information with pharmacies and primary care offices. But outside forces, such as problems with an electronic health record (EHR) system, can offset those effects.

The 3-year study, which will wrap up in the next few months, is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, with $1.5 million in funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

In the first phase of the study, researchers identified evidence-based techniques for taking the best possible medication history from hospitalized patients and synthesized them into a toolkit for clinicians. The free toolkit includes how-to videos and pocket cards. The second phase of the study is the mentored implementation of the techniques at five sites: two academic medical centers, two community hospitals, and one Veterans Affairs medical center.

Initial results from two of the five sites show that training on how to take a better medication history and clarity about who should be working on reconciling the medication list can help improve medication discrepancies. But while the interventions are promising, the initial case studies show mixed results.

While one community hospital site was able to lower medication discrepancies significantly, a second community hospital site had a spike in its medication discrepancies as it underwent a problematic implementation of a new EHR system.

Eighteen minutes to win it

At the first site, a Medication Reconciliation Assistant (MRA) program was used to improve the reliability of medication lists. The MRA is stationed in the emergency department and interviews patients about their medications and then verifies that list with the pharmacy, the primary care physician, or the skilled nursing facility. That new medication list is then handed off to the admitting physician. The process usually takes about 18-20 minutes.

They MRA program is staffed by four full-time employees, all pharmacy technicians with experience in retail pharmacies, who work 8-hour shifts throughout the week.

"It doesn’t have to be a pharmacy technician," said Dr. Jason Stein, a MARQUIS coinvestigator and a professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. "But somebody needs to be spending that 18 minutes doing something that roughly looks like this."

At that first site, unintentional medication discrepancies from either history or reconciliation errors dropped from 4.5 per patient at the in the preintervention period to 3.4 per patient. And the total number of potentially harmful discrepancies was reduced from 0.25 to 0.09 per patient.

At the second site, a smaller community hospital, the quality improvement team provided training to front-line providers on medication history taking and counseling at discharge and created a new hospital policy that clarified expectations about who would perform medication reconciliation and when they would do it. And recently, they began stationing a provider in the emergency department 5 days a week to work on medication reconciliation.

But shortly after the second hospital began implementing the MARQUIS interventions, the hospital launched a new EHR system that created problems for medication reconciliation. For instance, with the paper system, the admitting physician was accountable for the initial medication history. But under the electronic system, that accountability was lost. Also, the new EHR was unable to group medications as "continued," "changed," "stopped," or "new," making it difficult to perform discharge medication counseling.

The result was that, after some initial success, unintentional medication discrepancies spiked. In the preintervention period, unintentional medication discrepancies were 2.0 per patient, but they rose to nearly 5 discrepancies per patient after the rollout of the new EHR system. They have since fallen back down to 3.8 per patient. Similarly, the total of potentially harmful discrepancies rose from 0.20 to 1.11 per patient.

The free MARQUIS toolkit is available online.

On Twitter @maryellenny

LAS VEGAS – Tired of getting a patient medication list that isn’t reliable? A 3-year study on medication reconciliation could offer a roadmap for improving that list and reducing potentially harmful errors.

Preliminary results from MARQUIS (the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study) indicate that hospitals are able to reduce unintentional medication discrepancies by implementing a menu of interventions ranging from training providers to take a better medication history to stationing a designated provider in the emergency department to reconcile the patient’s information with pharmacies and primary care offices. But outside forces, such as problems with an electronic health record (EHR) system, can offset those effects.

The 3-year study, which will wrap up in the next few months, is sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, with $1.5 million in funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

In the first phase of the study, researchers identified evidence-based techniques for taking the best possible medication history from hospitalized patients and synthesized them into a toolkit for clinicians. The free toolkit includes how-to videos and pocket cards. The second phase of the study is the mentored implementation of the techniques at five sites: two academic medical centers, two community hospitals, and one Veterans Affairs medical center.

Initial results from two of the five sites show that training on how to take a better medication history and clarity about who should be working on reconciling the medication list can help improve medication discrepancies. But while the interventions are promising, the initial case studies show mixed results.

While one community hospital site was able to lower medication discrepancies significantly, a second community hospital site had a spike in its medication discrepancies as it underwent a problematic implementation of a new EHR system.

Eighteen minutes to win it

At the first site, a Medication Reconciliation Assistant (MRA) program was used to improve the reliability of medication lists. The MRA is stationed in the emergency department and interviews patients about their medications and then verifies that list with the pharmacy, the primary care physician, or the skilled nursing facility. That new medication list is then handed off to the admitting physician. The process usually takes about 18-20 minutes.

They MRA program is staffed by four full-time employees, all pharmacy technicians with experience in retail pharmacies, who work 8-hour shifts throughout the week.

"It doesn’t have to be a pharmacy technician," said Dr. Jason Stein, a MARQUIS coinvestigator and a professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. "But somebody needs to be spending that 18 minutes doing something that roughly looks like this."

At that first site, unintentional medication discrepancies from either history or reconciliation errors dropped from 4.5 per patient at the in the preintervention period to 3.4 per patient. And the total number of potentially harmful discrepancies was reduced from 0.25 to 0.09 per patient.

At the second site, a smaller community hospital, the quality improvement team provided training to front-line providers on medication history taking and counseling at discharge and created a new hospital policy that clarified expectations about who would perform medication reconciliation and when they would do it. And recently, they began stationing a provider in the emergency department 5 days a week to work on medication reconciliation.

But shortly after the second hospital began implementing the MARQUIS interventions, the hospital launched a new EHR system that created problems for medication reconciliation. For instance, with the paper system, the admitting physician was accountable for the initial medication history. But under the electronic system, that accountability was lost. Also, the new EHR was unable to group medications as "continued," "changed," "stopped," or "new," making it difficult to perform discharge medication counseling.

The result was that, after some initial success, unintentional medication discrepancies spiked. In the preintervention period, unintentional medication discrepancies were 2.0 per patient, but they rose to nearly 5 discrepancies per patient after the rollout of the new EHR system. They have since fallen back down to 3.8 per patient. Similarly, the total of potentially harmful discrepancies rose from 0.20 to 1.11 per patient.

The free MARQUIS toolkit is available online.

On Twitter @maryellenny

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM HOSPITAL MEDICINE 14

VIDEO: Hospitalists see opportunities in ACA rollout

LAS VEGAS – It’s been 4 years since Congress passed the Affordable Care Act and by now virtually all hospitalists have been impacted by some part of the law.

At the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine, leaders in the field grappled with the opportunities and challenges of implementing the controversial law.

On Twitter @maryellenny

LAS VEGAS – It’s been 4 years since Congress passed the Affordable Care Act and by now virtually all hospitalists have been impacted by some part of the law.

At the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine, leaders in the field grappled with the opportunities and challenges of implementing the controversial law.

On Twitter @maryellenny

LAS VEGAS – It’s been 4 years since Congress passed the Affordable Care Act and by now virtually all hospitalists have been impacted by some part of the law.