User login

Medical errors in all settings contributed to as many as 250,000 deaths per year in the United States between 2000 and 2008, according to a 2016 study.1 Diagnostic error, in particular, remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide. In 2017, 12 million patients (roughly 5% of all US adults) who sought outpatient care experienced missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis at least once.2

In his classic work, How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, explored the diagnostic process with a focus on the role of cognitive bias in clinical decision-making. Groopman examined how physicians can become sidetracked in their thinking and “blinded” to potential alternative diagnoses.3 Medical error is not necessarily because of a deficiency in medical knowledge; rather, physicians become susceptible to medical error when defective and faulty reasoning distort their diagnostic ability.4

Cognitive bias in the diagnostic process has been extensively studied, and a full review is beyond the scope of this article.5 However, here we will examine pathways leading to diagnostic errors in the primary care setting, specifically the role of cognitive bias in the work-up of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), ovarian cancer (OC), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and fibromyalgia (FM). As these 4 disease states are seen with low-to-moderate frequency in primary care, cognitive bias can complicate accurate diagnosis. But first, a word about how to understand clinical reasoning.

There are 2 types of reasoning (and 1 is more prone to error)

Physician clinical reasoning can be divided into 2 different cognitive approaches.

Type 1 reasoning employs intuition and heuristics; this type is automatic, reflexive, and quick.5 While the use of mental shortcuts in type 1 increases the speed with which decisions are made, it also makes this form of reasoning more prone to error.

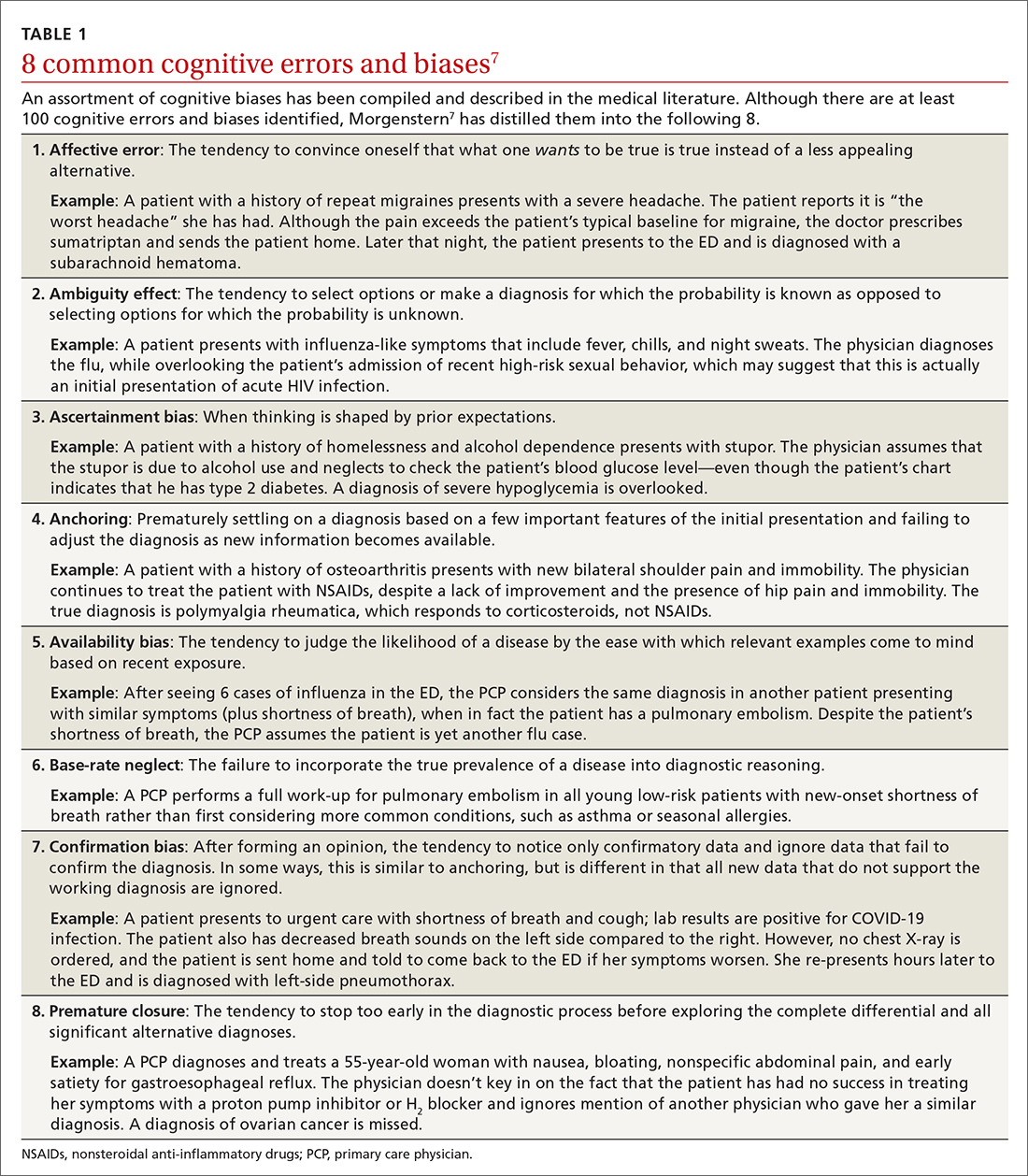

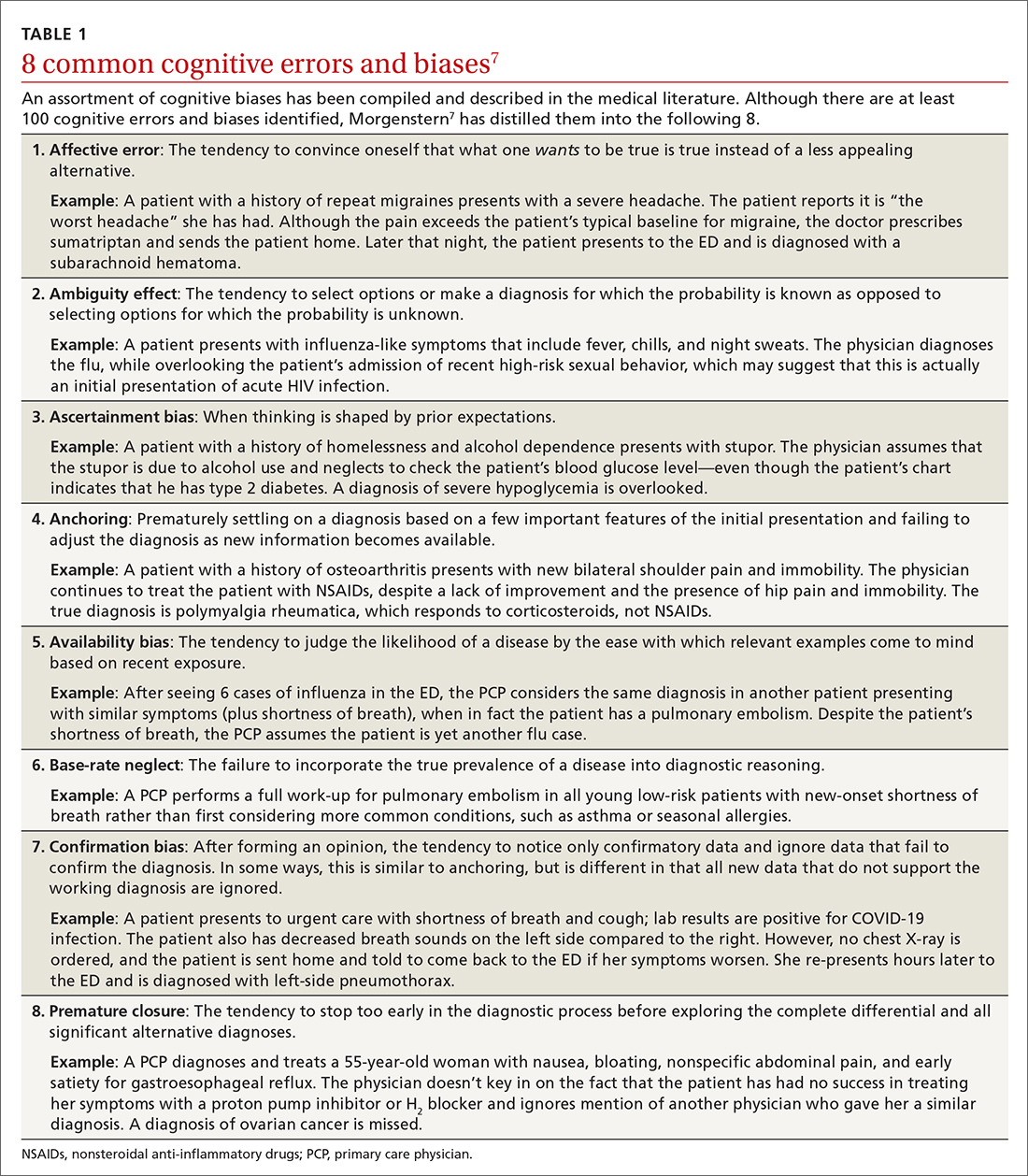

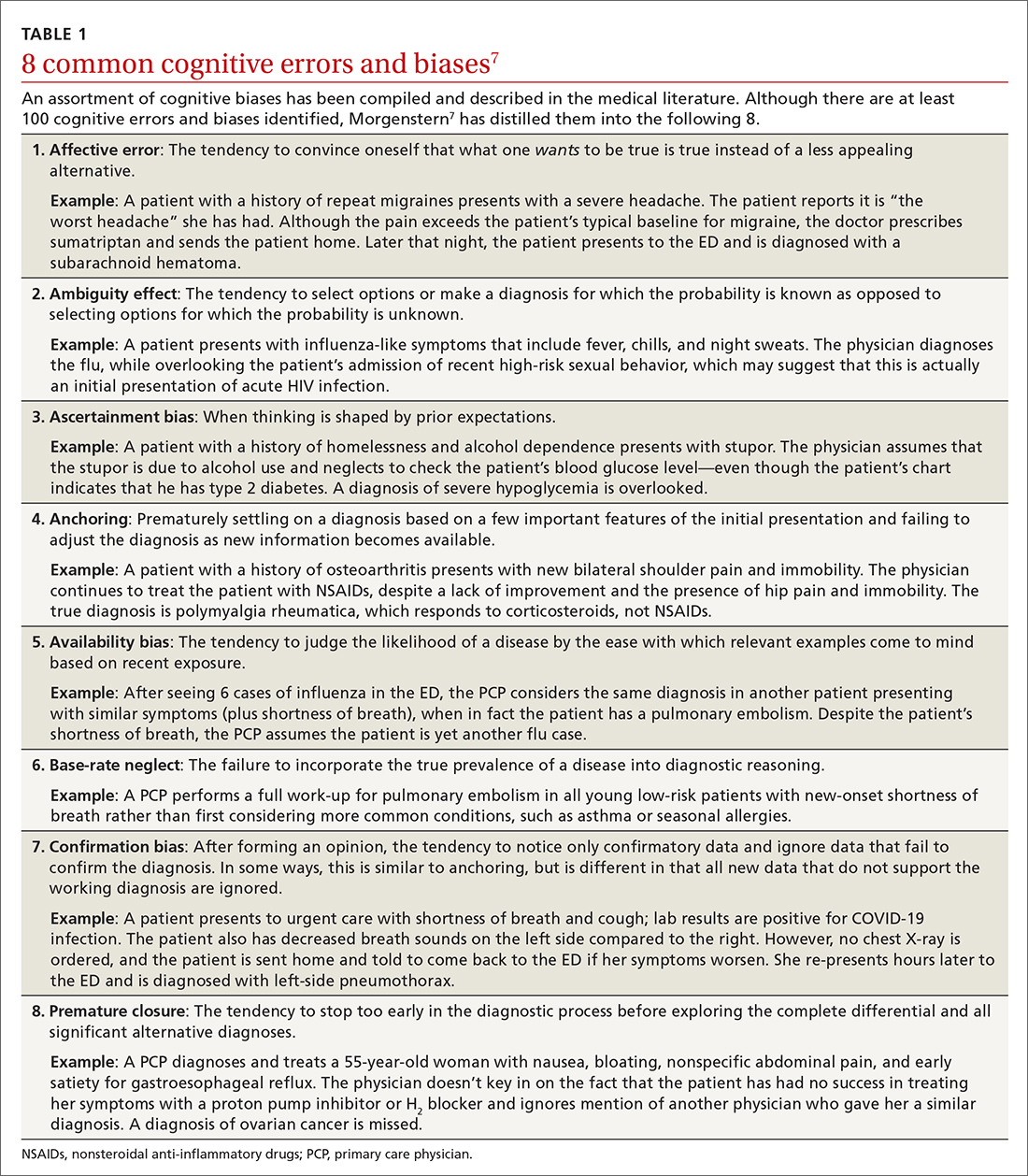

Type 2 reasoning requires conscious effort. It is goal directed and rigorous and therefore slower than type 1 reasoning. Extrapolated to the clinical context, clinicians transition from type 2 to type 1 reasoning as they gain experience and training throughout their careers and develop their own conscious and subconscious heuristics. Deviations from accurate decision-making occur in a systematic manner due to cognitive biases and result in medical error.6table 17 lists common types of cognitive bias.

An important question to ask. Physicians tend to fall into a pattern of quick, type 1 reasoning. However, it’s important to strive to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and avoid premature closure of the diagnostic process. It’s critical that we consider alternative diagnoses (ie, consciously move from type 1 to type 2 thinking) and continue to ask ourselves, “What else?” while working through differential diagnoses. This can be a powerful debiasing technique.

Continue to: The discussion...

The discussion of the following 4 disease states demonstrates how cognitive bias can lead to diagnostic error.

The patient is barely able to ambulate and appears to be in considerable pain. She is relying heavily on her walker and is assisted by her granddaughter. The primary care physician (PCP) obtains a detailed history that includes chronic shoulder and hip pain. Given that the patient has not responded to NSAID treatment over the previous 6 months, the PCP takes a moment to reconsider the diagnosis of OA and considers other options.

In light of the high prevalence of PMR in older women, the physician pursues a more specific physical examination tailored to ferret out PMR. He had learned this diagnostic shortcut as a resident, remembered it, and adeptly applied it whenever circumstances warranted. He asks the patient to raise her arms above her head (goalpost sign). She is unable to perform this task and experiences severe bilateral shoulder pain on trial. The PCP then places the patient on the examining table and attempts to assist her in rolling toward him. The patient is also unable to perform this maneuver and experiences significant bilateral hip pain on trial.

Based primarily on the patient’s history and physical exam findings, the PCP makes a presumptive diagnosis of PMR vs OA vs combined PMR with OA, orders an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and basic rheumatologic

PMR can be mistaken for OA

PMR is the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease in older patients.8 It is a debilitating illness with simple, effective treatment but has devastating consequences if missed or left untreated.9 PMR typically manifests in patients older than age 50, with a peak incidence at 80 years of age. It is also far more common in women.10

Approximately 80% of patients with PMR initially present to their PCP, often posing a diagnostic challenge to many clinicians.11 Due to overlap in symptoms, the condition is often misdiagnosed as OA, a more common condition seen by PCPs. Also, there are no specific diagnostic tests for PMR. An elevated ESR can help confirm the diagnosis, but one-third of patients with PMR have a normal ESR.12 Therefore, the diagnostic conundrum the physician faces is OA vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PMR, or another condition.

Continue to: The consequences...

The consequences of a missed and delayed PMR diagnosis range from seriously impaired quality of life to significantly increased risk of vascular events (eg, blindness, stroke) due to temporal arteritis.13 Early diagnosis is even more critical as the risk of a vascular event and death is highest during initial phases of the disease course.14

FPs often miss this Dx. A timely diagnosis relies almost exclusively on an accurate, thorough history and physical exam. However, PCPs often struggle to correctly diagnose PMR. According to a study by Bahlas and colleagues,15 the accuracy rate for correctly diagnosing PMR was 24% among a cohort of family physicians.

The differential diagnosis for PMR is broad and includes seronegative spondyloarthropathies, malignancy, Lyme disease, hypothyroidism, and both RA and OA.16

PCPs are extremely adept at correctly diagnosing RA, but not PMR. A study by Blaauw and colleagues17 comparing PCPs and rheumatologists found PCPs correctly identified 92% of RA cases but only 55% of PMR cases. When rheumatologists reviewed these same cases, they correctly identified PMR and RA almost 100% of the time.17 The difference in diagnostic accuracy between rheumatologists and PCPs suggests limited experience and gaps in fund of knowledge.

Making the diagnosis. The diagnosis of PMR is often made on empiric response to corticosteroid treatment, but doing so based solely on a patient’s response is controversial.18 There are rare instances in which patients with PMR fail to respond to treatment. On the other hand, some inflammatory conditions that mimic or share symptoms with PMR also respond to corticosteroids, potentially resulting in erroneous confirmation bias.

Some classification criteria use rapid response to low-dose prednisone/prednisolone (≤ 20 mg) to confirm the diagnosis,19 while other more recent guidelines no longer include this approach.20 If PMR continues to be suspected after a trial of steroids is unsuccessful, the PCP can try another course of higher dose steroids or consult with Rheumatology.

Continue to: A full history...

A full history and physical exam revealed a myriad of gastrointestinal (GI) complaints, such as diarrhea. But the PCP recalled a recent roundtable discussion on debiasing techniques specifically related to gynecologic disorders, including OC. Therefore, he decided to include OC in the differential diagnosis—something he would not routinely have done given the preponderance of GI symptoms. Despite the patient’s reluctance and time constraints, the PCP ordered a transvaginal ultrasound. Findings from the ultrasound study revealed stage II OC, which carries a good prognosis. The patient is currently undergoing treatment and was last reported as doing well.

Early signs of ovarian cancer can be chalked up to a “GI issue”

OC is the second most common gynecologic cancer21 and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death22 in US women. Compared to other cancers, the prognosis for localized early-stage OC is surprisingly good, with a 5-year survival rate approaching 93%.23 However, most disease is detected in later stages, and the 5-year survival rate drops to a low of 29%.24

There remains no established screening protocol for OC. Fewer than a quarter of all cases are diagnosed in stage I, and detection of OC relies heavily on the physician’s ability to decipher vague symptomatology that overlaps with other, more common maladies. This poses an obvious diagnostic challenge and, not surprisingly, a high level of susceptibility to cognitive bias.

More than 90% of patients with OC present with some combination of the following symptoms prior to diagnosis: abdominal (77%), GI (70%), pain (58%), constitutional (50%), urinary (34%), and pelvic (26%).25 The 3 most common isolated symptoms in patients with OC are abdominal bloating, decrease in appetite, and frank abdominal pain.26 Patients with biopsy-confirmed OC experience these symptoms an average of 6 months prior to actual diagnosis.27

Knowledge gaps play a role. Studies assessing the ability of health care providers to identify presenting symptoms of OC reveal specific knowledge gaps. For instance, in a survey by Gajjar and colleagues,28 most PCPs correctly identified bloating as a key symptom of OC; however, they weren’t as good at identifying less common symptoms, such as inability to finish a meal and early satiety. Moreover, survey participants misinterpreted or missed GI symptoms as an important manifestation of early OC disease.28 These specific knowledge gaps combine with physician errors in thinking, further obscuring and extending the diagnostic process. The point prevalence for OC is relatively low, and many PCPs only encounter a few cases during their entire career.29 This low pre-test probability may also fuel the delay in diagnosis.

Watch for these forms of bias. Since nonspecific symptoms of early-stage OC resemble those of other more benign conditions, a form of anchoring error known as multiple alternatives bias can arise. In this scenario, clinicians investigate only 1 potential plausible diagnosis and remain focused on that single, often faulty, conclusion. This persists despite other equally plausible alternatives that arise as the investigation proceeds.28

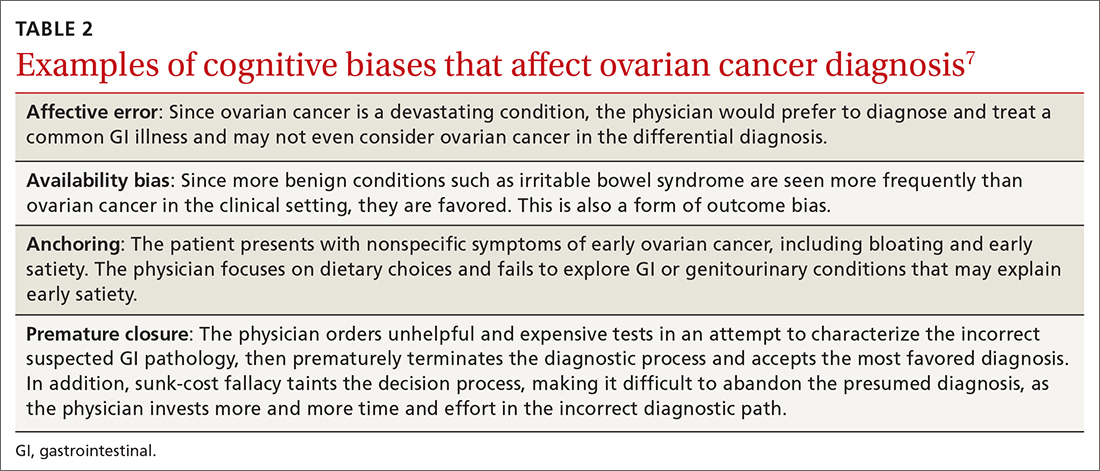

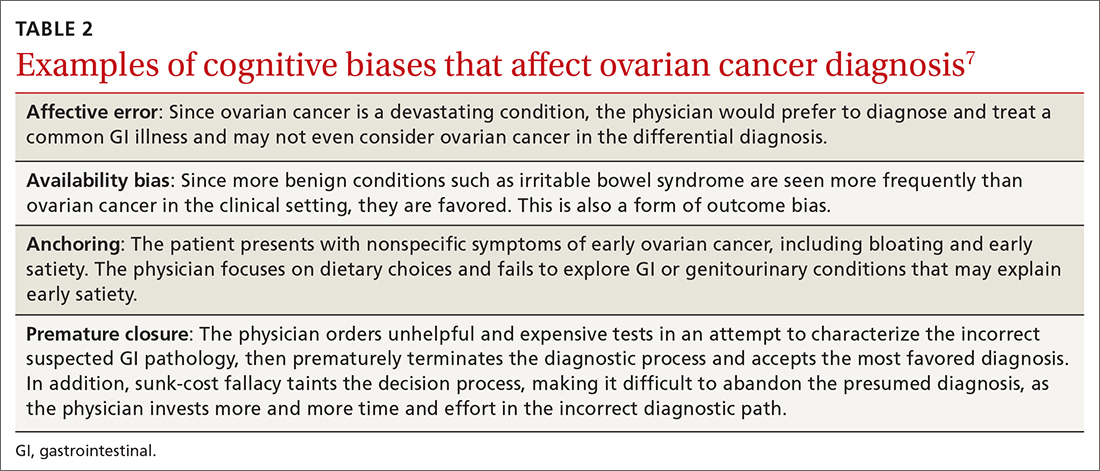

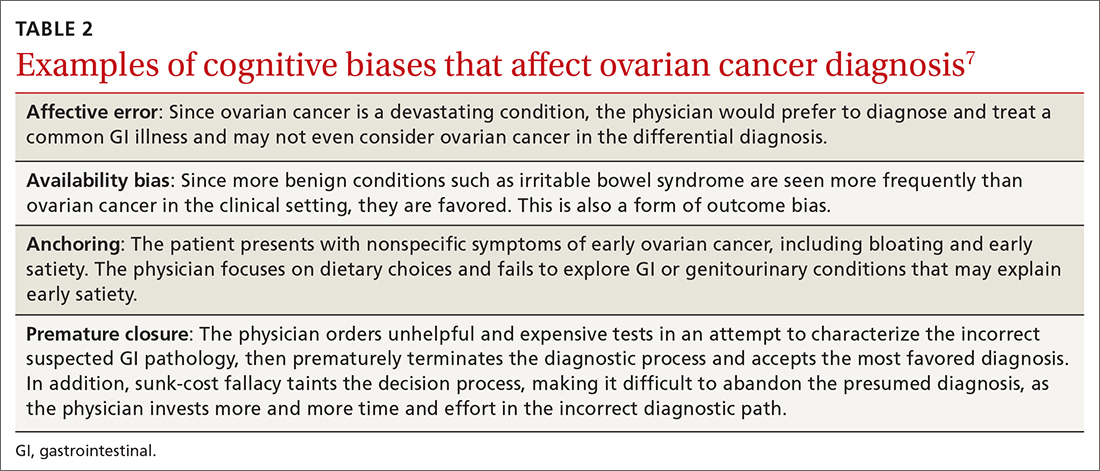

Affective error may also play a role in missed or delayed diagnosis. For example, a physician would prefer to diagnose and treat a common GI illness than consider OC. Another distortion involves outcome bias wherein the physician gives more significance to benign conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome because they have a more favorable outcome and clear treatment path. Physicians also favor these benign conditions because they encounter them more frequently than OC in the clinic setting. (This is known as availability bias.) Outcome bias and multiple alternatives bias can result in noninvestigation of symptoms and inefficient or improper management, leading to a delay in arriving at the correct diagnosis or anchoring on a plausible but incorrect diagnosis.

Continue to: An incorrect initial diagnostic...

An incorrect initial diagnostic path often triggers a cascade of subsequent errors. The physician orders additional unhelpful and expensive tests in an effort to characterize the suspected GI pathology. This then leads the physician to prematurely terminate the work-up and accept the most favored diagnosis. Lastly, sunk-cost fallacy comes into play: The physician has “invested” time and energy investigating a particular diagnosis and rather than abandon the presumed diagnosis, continues to put more time and effort in going down an incorrect diagnostic path.

A series of failures. These biases and miscues have been observed in several studies. For example, a survey of 1725 women by Goff and colleagues30 sought to identify factors related to delayed OC diagnosis. The authors found that the following factors were significantly associated with a delayed diagnosis: omission of a pelvic exam at initial presentation, a separate exploration of a multitude of collateral symptoms, a failure to order ultrasound/computed tomography/CA-125 test, and a failure to consider age as a factor (especially if the patient was outside the norm).

Responses from the survey also revealed that physicians initially ordered work-ups related to GI etiology and only later considered a pelvic work-up. This suggests that well-known presenting signs and symptoms or a constellation of typical and atypical symptoms of OC often failed to trigger physician recognition. Understandably, patients presenting with menorrhagia or gynecologic complaints are more likely to have OC detected at an earlier stage than patients who present with GI or abdominal signs alone.31 table 27 summarizes some of the cognitive biases seen in the diagnostic path of OC.

While in the hospital, he becomes acutely upset by the hallucinations and is given haloperidol and lorazepam by house staff. In the morning, the patient exhibits severe signs of Parkinson disease that include rigidity and masked facies.

Given the patient’s poor response to haloperidol and continued confusion, the team consulted Neurology and Psychiatry. Gathering a more detailed history from the patient and family, the patient is given a diagnosis of classic LBD. The antipsychotic medications are stopped. The patient and his family receive education about LBD treatment and management, and the patient is discharged to outpatient care.

Psychiatric symptoms can be an early “misdirect” in cases of Lewy body disease

LBD, the second leading neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD), affects 1.5 million Americans,32 representing about 10% of all dementia cases. LBD and AD overlap in 25% of dementia cases.33 In patients older than 85 years, the prevalence jumps to 5% of the general population and 22% of all cases of dementia.33 Despite its prevalence, a recent study showed that only 6% of PCPs correctly identified LBD as the primary diagnosis when presented with typical case examples.32

Continue to: 3 stages of presentation

3 stages of presentation. Unlike other forms of dementia, LBD typically presents first with psychiatric symptoms, then with cognitive impairment, and last with parkinsonian symptoms. Additionally, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and often subtle elements of nonmemory cognitive impairment distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia.32 The primary cognitive deficit in LBD is not in memory but in attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability.34 Only in the later stages of the disease do patients exhibit gradual and progressive memory loss.

Mistaken for many things. When evaluating patients exhibiting signs of dementia, it’s important to include LBD in the differential, with increased suspicion for patients experiencing episodes of psychosis or delirium. The uniqueness of LBD lies in its psychotic symptomatology, particularly during earlier stages of the disease. This feature helps distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia. As seen in the case, LBD can also be confused with acute delirium.

Older adult patients presenting to the ED or clinic with visual hallucinations, delirium, and mental confusion may receive a false diagnosis of schizophrenia, medication- or substance-induced psychosis, Parkinson disease, or delirium of unknown etiology.35 Unfortunately, LBD is often overlooked and not considered in the differential diagnosis. Due to underrecognition, patients may receive treatment with typical antipsychotics. The addition of a neuroleptic to help control the psychotic symptoms causes patients with LBD to develop severe extrapyramidal symptoms and worsening mental status,36 leading to severe parkinsonian signs, which further muddies the diagnostic process. In addition, treatment for suspected Parkinson disease, including carbidopa-levodopa, has no benefit for patients with LBD and may increase psychotic symptoms.37

First-line treatment for LBD includes psychoeducation for the patient and family, cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, rivastigmine), and avoidance of high-potency antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. Although persistent hallucinations and psychosis remain difficult to treat in LBD, low-dose quetiapine is 1 option. Incorrectly diagnosing and prescribing treatment for another condition exacerbates symptoms in this patient population.

The patient has been experiencing chronic pain for the past few years after a motor vehicle accident. She has seen a physiatrist and another provider, both of whom found no “objective” causes of her chronic pain. They started the patient on sertraline for depression and an analgesic, both of which were ineffective.

The patient likes to exercise at a gym twice a week by doing light cardio (treadmill) exercise and light weightlifting. Lately, however, she has been unable to exercise due to the pain. At this visit, she mentions having low energy, poor sleep, frequent fatigue, and generalized soreness and pain in multiple areas of her body. The PCP recognizes the patient’s presenting symptoms as significant for FM and starts her on pregabalin and hydrotherapy, with positive results.

Continue to: Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

FM, the second most common disorder seen in rheumatologic practice after OA, is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 20 patients (approximately 5 million Americans) in the primary care setting.38,39 The condition has a high female-to-male preponderance (3.4% vs 0.5%).40 While the primary symptom of FM is chronic pain, patients commonly present with fatigue and sleep disturbance.41 Comorbid conditions include headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and mood disturbances (most commonly anxiety and depression).

Several studies have explored reasons for the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of FM. One important factor is ongoing skepticism among some physicians and the public, in general, as to whether FM is a real disease. This issue was addressed by a study by White and colleagues,42 who estimated and compared the point prevalence of FM and related disorders in Amish vs non-Amish adults. The authors hypothesized that if litigation and/or compensation availability have a major impact on FM prevalence, then there would be a near zero prevalence of FM in the Amish community. And yet, researchers found an overall age- and sex-adjusted FM prevalence of 7.3% (95% CI; 5.3%-9.7%); this was both statistically greater than zero (P < .0001) and greater than 2 control populations of non-Amish adults (both P < .05).

Many physicians consider FM fundamentally an emotional disturbance, and the high preponderance of FM in female patients may contribute to this misconception as reports of pain and emotional distress by women are often dismissed as hysteria.43 Physicians often explore the emotional aspects of FM, incorrectly diagnosing patients with depression and subsequently treating them with a psychotropic drug.39 Alternatively, they may focus on the musculoskeletal presentations of FM and prescribe analgesics or physical therapy, both of which do little to alleviate FM.

To make the correct diagnosis of FM, the American College of Rheumatology created a specific set of criteria in 1990, which was updated in 2010.44 For a diagnosis of FM, a patient must have at least a 3-month history of bilateral pain above and below the waist and along the axial skeletal spine. Although not included in the updated 2010 criteria, many clinicians continue to check for tender points, following the 1990 criteria requiring the presence of 11 of 18 points to make the diagnosis.

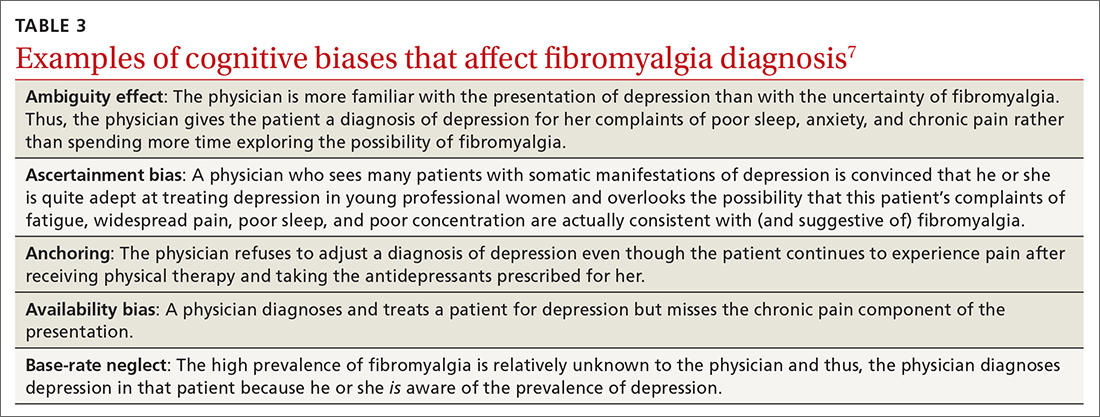

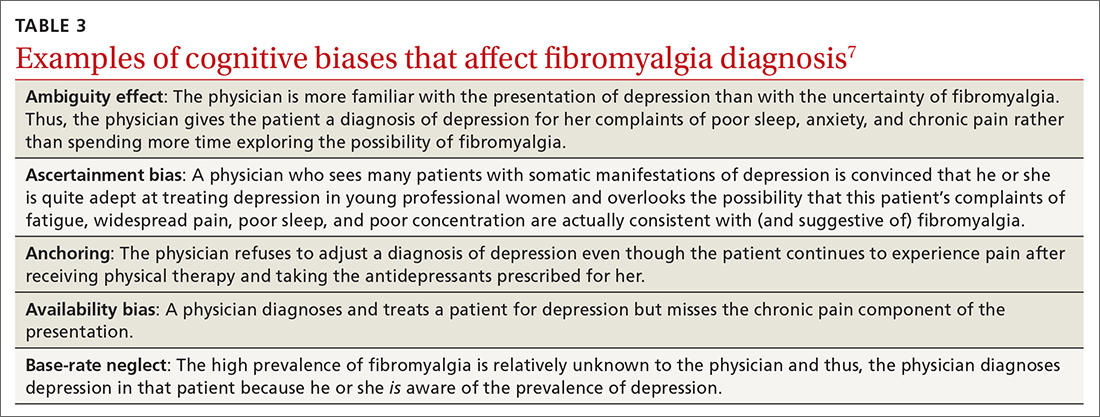

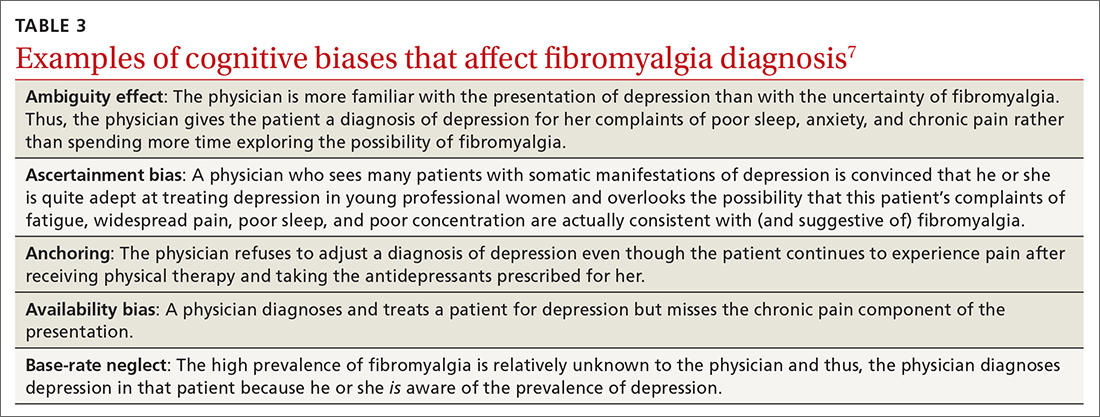

At least 3 cognitive biases relating to FM apply: anchoring, availability, and fundamental attribution error (see table 3).7 Anchoring occurs when the PCP settles on a psychiatric diagnosis of exaggerated pain syndrome, muscle overuse, or OA and fails to explore alternative etiology. Availability bias may obscure the true diagnosis of FM. Since PCPs see many patients with RA or OA, they may overlook or dismiss the possibility of FM. Attribution error happens when physicians dismiss the complaints of patients with FM as merely due to psychological distress, hysteria, or acting out.43

Patients with FM, who are often otherwise healthy, often present multiple times to the same PCP with a chief complaint of chronic pain. These repeat presentations can result in compassion fatigue and impact care. As Aloush and colleagues40 noted in their study, “FM patients were perceived as more difficult than RA patients, with a high level of concern and emotional response. A high proportion of physicians were reluctant to accept them because they feel emotional/psychological difficulties meeting and coping with these patients.”In response, patients with undiagnosed FM or inadequately treated FM may visit other PCPs, which may or may not result in a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We can do better

Primary care physicians face the daunting task of diagnosing and treating a wide range of common conditions while also trying to recognize less-common conditions with atypical presentations—all during a busy clinic workday. Nonetheless, we should strive to overcome internal (eg, cognitive bias and fund-of-knowledge deficits) and external (eg, time constraints, limited resources) pressures to improve diagnostic accuracy and care.

Each of the 4 disease states we’ve discussed have high rates of missed and/or delayed diagnosis. Each presents a unique set of confounders: PMR with its overlapping symptoms of many other rheumatologic diseases; OC with its often vague and misleading GI symptomatology; LBD with overlapping features of AD and Parkinson disease; and FM with skepticism. As gatekeepers to health care, it falls on PCPs to sort out these diagnostic dilemmas to avoid medical errors. Fundamental knowledge of each disease, its unique pathophysiology and symptoms, and varying presentations can be learned, internalized, and subsequently put into clinical practice to improve patient outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul D. Rosen MD, Brooklyn Hospital Center, Department of Family Medicine, 121 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11201; [email protected]

1. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139

2. Van Such M, Lohr R, Beckman T, et al. Extent of diagnostic agreement among medical referrals. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:870-874. doi: 10.1111/jep.12747

3. Groopman JE. How Doctors Think. Houghton Mifflin; 2007.

4. Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124-1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

5. Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, et al. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: Cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med. 2017;92:23-30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

6. Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775-780. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003

7. Morgenstern J. Cognitive errors in medicine: The common errors. First10EM blog. September 15, 2015. Updated September 22, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://first10em.com/cognitive-errors/

8. Gazitt T, Zisman D, Gardner G. Polymyalgia rheumatica: a common disease in seniors. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22:40. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00919-2

9. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176

10. Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, et al. Trends in the incidence of polymyalgia rheumatica over a 30 year period in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1694-1697.

11. Barraclough K, Liddell WG, du Toit J, et al. Polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: a cohort study of the diagnostic criteria and outcome. Fam Pract. 2008;25:328-33. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn044

12. Manzo C. Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) with normal values of both erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration at the time of diagnosis in a centenarian man: a case report. Diseases. 2018;6:84. doi: 10.3390/diseases6040084

13. Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Contemporary prevalence estimates for giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica, 2015. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:253-256. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.04.001

14. Nordborg E, Bengtsson BA. Death rates and causes of death in 284 consecutive patients with giant cell arteritis confirmed by biopsy. BMJ. 1989;299:549-550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6698.549

15. Bahlas S, Ramos-Remus C, Davis P. Utilisation and costs of investigations, and accuracy of diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica by family physicians. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:278-280. doi: 10.1007/s100670070045

16. Brooks RC, McGee SR. Diagnostic dilemmas in polymyalgia rheumatica. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:162-168.

17. Blaauw AA, Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP, et al. Assessing clinical competence: recognition of case descriptions of rheumatic diseases by general practitioners. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:375-379. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/34.4.375

18. Mager DR. Polymylagia rheumatica: common disease, elusive diagnosis. Home Healthc Now. 2015;33:132-138. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000000199

19. Kermani TA, Warrington KJ. Polymyalgia rheumatica. Lancet. 381;63-72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60680-1. Published correction appears in Lancet. 20135;381:28.

20. Liew DF, Owen CE, Buchanan RR. Prescribing for polymyalgia rheumatica. Aust Prescr. 2018;41:14-19. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2018.001

21. Ovarian cancer statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed June 8, 2021. Accessed February 22, 2022. www.cdc.gov/cancer/ovarian/statistics/index.htm

22. Key statistics for ovarian cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 12, 2022. Accessed February 22, 2022. www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

23. Survival rates for ovarian cancer. American Cancer Society. Revised January 25, 2021. Accessed February 22, 2022. www.cancer.org/cancer/ovarian-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

24. Reid BM, Permuth JB, Sellers TA. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a review. Cancer Biol Med. 2017;14:9-32. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0084

25. Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, et al. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004;291:2705-2712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2705

26. Olson SH, Mignone L, Nakraseive C, et al. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:212-217. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01457-0

27. Allgar VL, Neal RD. Delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: analysis of data from the National Survey of NHS patients: Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1959-1970. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602587

28. Gajjar K, Ogden G, Mujahid MI, et al. Symptoms and risk factors of ovarian cancer: a survey in primary care. Obstet Gynecol. 2012:754197. doi: 10.5402/2012/754197

29. Austoker J. Diagnosis of ovarian cancer in primary care. BMJ. 2009;339:b3286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3286

30. Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, et al. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis: results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer. 2000;89:2068-2075. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001115)89:10<2068::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-z

31. Smith EM, Anderson B. The effects of symptoms and delay in seeking diagnosis on stage of disease at diagnosis among women with cancers of the ovary. Cancer. 1985;56:2727-2732. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851201)56:11<2727::aid-cncr2820561138>3.0.co;2-8

32. Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, et al. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:388-392. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.03.007

33. McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6:333-341. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2004.6.3/imckeith

34. Mrak RE, Griffin WS. Dementia with Lewy bodies: definitions, diagnosis, and pathogenic relationship to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:619-625.

35. Khotianov N, Singh R, Singh S. Lewy body dementia: case report and discussion. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:50-54.

36. Stinton C, McKeith I, Taylor JP, et al. Pharmacological management of Lewy body dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:731-742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121582

37. Velayudhan L, Ffytche D, Ballard C, et al. New therapeutic strategies of Lewy body dementias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:68. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0778-2

38. Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, McCarberg BH; FibroCollaborative. Improving the recognition and diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:457-464. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0738

39. Arnold LM, Gebke KB, Choy EHS. Fibromyalgia: management strategies for primary care providers. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70:99-112. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12757

40. Aloush V, Niv D, Ablin JN, et al. Good pain, bad pain: illness perception and physician attitudes towards rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(suppl 130):54-60.

41. Vincent A, Lahr BD, Wolfe F, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:786-792. doi: 10.1002/acr.21896

42. White KP, Thompson J. Fibromyalgia syndrome in an Amish community: a controlled study to determine disease and symptom prevalence. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1835-1840.

43. Lobo CP, Pfalzgraf AR, Giannetti V, et al. Impact of invalidation and trust in physicians on health outcomes in fibromyalgia patients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16:10.4088/PCC.14m01664. doi: 10.4088/PCC.14m01664

44. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:600-610. doi:10.1002/acr.20140

Medical errors in all settings contributed to as many as 250,000 deaths per year in the United States between 2000 and 2008, according to a 2016 study.1 Diagnostic error, in particular, remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide. In 2017, 12 million patients (roughly 5% of all US adults) who sought outpatient care experienced missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis at least once.2

In his classic work, How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, explored the diagnostic process with a focus on the role of cognitive bias in clinical decision-making. Groopman examined how physicians can become sidetracked in their thinking and “blinded” to potential alternative diagnoses.3 Medical error is not necessarily because of a deficiency in medical knowledge; rather, physicians become susceptible to medical error when defective and faulty reasoning distort their diagnostic ability.4

Cognitive bias in the diagnostic process has been extensively studied, and a full review is beyond the scope of this article.5 However, here we will examine pathways leading to diagnostic errors in the primary care setting, specifically the role of cognitive bias in the work-up of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), ovarian cancer (OC), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and fibromyalgia (FM). As these 4 disease states are seen with low-to-moderate frequency in primary care, cognitive bias can complicate accurate diagnosis. But first, a word about how to understand clinical reasoning.

There are 2 types of reasoning (and 1 is more prone to error)

Physician clinical reasoning can be divided into 2 different cognitive approaches.

Type 1 reasoning employs intuition and heuristics; this type is automatic, reflexive, and quick.5 While the use of mental shortcuts in type 1 increases the speed with which decisions are made, it also makes this form of reasoning more prone to error.

Type 2 reasoning requires conscious effort. It is goal directed and rigorous and therefore slower than type 1 reasoning. Extrapolated to the clinical context, clinicians transition from type 2 to type 1 reasoning as they gain experience and training throughout their careers and develop their own conscious and subconscious heuristics. Deviations from accurate decision-making occur in a systematic manner due to cognitive biases and result in medical error.6table 17 lists common types of cognitive bias.

An important question to ask. Physicians tend to fall into a pattern of quick, type 1 reasoning. However, it’s important to strive to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and avoid premature closure of the diagnostic process. It’s critical that we consider alternative diagnoses (ie, consciously move from type 1 to type 2 thinking) and continue to ask ourselves, “What else?” while working through differential diagnoses. This can be a powerful debiasing technique.

Continue to: The discussion...

The discussion of the following 4 disease states demonstrates how cognitive bias can lead to diagnostic error.

The patient is barely able to ambulate and appears to be in considerable pain. She is relying heavily on her walker and is assisted by her granddaughter. The primary care physician (PCP) obtains a detailed history that includes chronic shoulder and hip pain. Given that the patient has not responded to NSAID treatment over the previous 6 months, the PCP takes a moment to reconsider the diagnosis of OA and considers other options.

In light of the high prevalence of PMR in older women, the physician pursues a more specific physical examination tailored to ferret out PMR. He had learned this diagnostic shortcut as a resident, remembered it, and adeptly applied it whenever circumstances warranted. He asks the patient to raise her arms above her head (goalpost sign). She is unable to perform this task and experiences severe bilateral shoulder pain on trial. The PCP then places the patient on the examining table and attempts to assist her in rolling toward him. The patient is also unable to perform this maneuver and experiences significant bilateral hip pain on trial.

Based primarily on the patient’s history and physical exam findings, the PCP makes a presumptive diagnosis of PMR vs OA vs combined PMR with OA, orders an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and basic rheumatologic

PMR can be mistaken for OA

PMR is the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease in older patients.8 It is a debilitating illness with simple, effective treatment but has devastating consequences if missed or left untreated.9 PMR typically manifests in patients older than age 50, with a peak incidence at 80 years of age. It is also far more common in women.10

Approximately 80% of patients with PMR initially present to their PCP, often posing a diagnostic challenge to many clinicians.11 Due to overlap in symptoms, the condition is often misdiagnosed as OA, a more common condition seen by PCPs. Also, there are no specific diagnostic tests for PMR. An elevated ESR can help confirm the diagnosis, but one-third of patients with PMR have a normal ESR.12 Therefore, the diagnostic conundrum the physician faces is OA vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PMR, or another condition.

Continue to: The consequences...

The consequences of a missed and delayed PMR diagnosis range from seriously impaired quality of life to significantly increased risk of vascular events (eg, blindness, stroke) due to temporal arteritis.13 Early diagnosis is even more critical as the risk of a vascular event and death is highest during initial phases of the disease course.14

FPs often miss this Dx. A timely diagnosis relies almost exclusively on an accurate, thorough history and physical exam. However, PCPs often struggle to correctly diagnose PMR. According to a study by Bahlas and colleagues,15 the accuracy rate for correctly diagnosing PMR was 24% among a cohort of family physicians.

The differential diagnosis for PMR is broad and includes seronegative spondyloarthropathies, malignancy, Lyme disease, hypothyroidism, and both RA and OA.16

PCPs are extremely adept at correctly diagnosing RA, but not PMR. A study by Blaauw and colleagues17 comparing PCPs and rheumatologists found PCPs correctly identified 92% of RA cases but only 55% of PMR cases. When rheumatologists reviewed these same cases, they correctly identified PMR and RA almost 100% of the time.17 The difference in diagnostic accuracy between rheumatologists and PCPs suggests limited experience and gaps in fund of knowledge.

Making the diagnosis. The diagnosis of PMR is often made on empiric response to corticosteroid treatment, but doing so based solely on a patient’s response is controversial.18 There are rare instances in which patients with PMR fail to respond to treatment. On the other hand, some inflammatory conditions that mimic or share symptoms with PMR also respond to corticosteroids, potentially resulting in erroneous confirmation bias.

Some classification criteria use rapid response to low-dose prednisone/prednisolone (≤ 20 mg) to confirm the diagnosis,19 while other more recent guidelines no longer include this approach.20 If PMR continues to be suspected after a trial of steroids is unsuccessful, the PCP can try another course of higher dose steroids or consult with Rheumatology.

Continue to: A full history...

A full history and physical exam revealed a myriad of gastrointestinal (GI) complaints, such as diarrhea. But the PCP recalled a recent roundtable discussion on debiasing techniques specifically related to gynecologic disorders, including OC. Therefore, he decided to include OC in the differential diagnosis—something he would not routinely have done given the preponderance of GI symptoms. Despite the patient’s reluctance and time constraints, the PCP ordered a transvaginal ultrasound. Findings from the ultrasound study revealed stage II OC, which carries a good prognosis. The patient is currently undergoing treatment and was last reported as doing well.

Early signs of ovarian cancer can be chalked up to a “GI issue”

OC is the second most common gynecologic cancer21 and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death22 in US women. Compared to other cancers, the prognosis for localized early-stage OC is surprisingly good, with a 5-year survival rate approaching 93%.23 However, most disease is detected in later stages, and the 5-year survival rate drops to a low of 29%.24

There remains no established screening protocol for OC. Fewer than a quarter of all cases are diagnosed in stage I, and detection of OC relies heavily on the physician’s ability to decipher vague symptomatology that overlaps with other, more common maladies. This poses an obvious diagnostic challenge and, not surprisingly, a high level of susceptibility to cognitive bias.

More than 90% of patients with OC present with some combination of the following symptoms prior to diagnosis: abdominal (77%), GI (70%), pain (58%), constitutional (50%), urinary (34%), and pelvic (26%).25 The 3 most common isolated symptoms in patients with OC are abdominal bloating, decrease in appetite, and frank abdominal pain.26 Patients with biopsy-confirmed OC experience these symptoms an average of 6 months prior to actual diagnosis.27

Knowledge gaps play a role. Studies assessing the ability of health care providers to identify presenting symptoms of OC reveal specific knowledge gaps. For instance, in a survey by Gajjar and colleagues,28 most PCPs correctly identified bloating as a key symptom of OC; however, they weren’t as good at identifying less common symptoms, such as inability to finish a meal and early satiety. Moreover, survey participants misinterpreted or missed GI symptoms as an important manifestation of early OC disease.28 These specific knowledge gaps combine with physician errors in thinking, further obscuring and extending the diagnostic process. The point prevalence for OC is relatively low, and many PCPs only encounter a few cases during their entire career.29 This low pre-test probability may also fuel the delay in diagnosis.

Watch for these forms of bias. Since nonspecific symptoms of early-stage OC resemble those of other more benign conditions, a form of anchoring error known as multiple alternatives bias can arise. In this scenario, clinicians investigate only 1 potential plausible diagnosis and remain focused on that single, often faulty, conclusion. This persists despite other equally plausible alternatives that arise as the investigation proceeds.28

Affective error may also play a role in missed or delayed diagnosis. For example, a physician would prefer to diagnose and treat a common GI illness than consider OC. Another distortion involves outcome bias wherein the physician gives more significance to benign conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome because they have a more favorable outcome and clear treatment path. Physicians also favor these benign conditions because they encounter them more frequently than OC in the clinic setting. (This is known as availability bias.) Outcome bias and multiple alternatives bias can result in noninvestigation of symptoms and inefficient or improper management, leading to a delay in arriving at the correct diagnosis or anchoring on a plausible but incorrect diagnosis.

Continue to: An incorrect initial diagnostic...

An incorrect initial diagnostic path often triggers a cascade of subsequent errors. The physician orders additional unhelpful and expensive tests in an effort to characterize the suspected GI pathology. This then leads the physician to prematurely terminate the work-up and accept the most favored diagnosis. Lastly, sunk-cost fallacy comes into play: The physician has “invested” time and energy investigating a particular diagnosis and rather than abandon the presumed diagnosis, continues to put more time and effort in going down an incorrect diagnostic path.

A series of failures. These biases and miscues have been observed in several studies. For example, a survey of 1725 women by Goff and colleagues30 sought to identify factors related to delayed OC diagnosis. The authors found that the following factors were significantly associated with a delayed diagnosis: omission of a pelvic exam at initial presentation, a separate exploration of a multitude of collateral symptoms, a failure to order ultrasound/computed tomography/CA-125 test, and a failure to consider age as a factor (especially if the patient was outside the norm).

Responses from the survey also revealed that physicians initially ordered work-ups related to GI etiology and only later considered a pelvic work-up. This suggests that well-known presenting signs and symptoms or a constellation of typical and atypical symptoms of OC often failed to trigger physician recognition. Understandably, patients presenting with menorrhagia or gynecologic complaints are more likely to have OC detected at an earlier stage than patients who present with GI or abdominal signs alone.31 table 27 summarizes some of the cognitive biases seen in the diagnostic path of OC.

While in the hospital, he becomes acutely upset by the hallucinations and is given haloperidol and lorazepam by house staff. In the morning, the patient exhibits severe signs of Parkinson disease that include rigidity and masked facies.

Given the patient’s poor response to haloperidol and continued confusion, the team consulted Neurology and Psychiatry. Gathering a more detailed history from the patient and family, the patient is given a diagnosis of classic LBD. The antipsychotic medications are stopped. The patient and his family receive education about LBD treatment and management, and the patient is discharged to outpatient care.

Psychiatric symptoms can be an early “misdirect” in cases of Lewy body disease

LBD, the second leading neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD), affects 1.5 million Americans,32 representing about 10% of all dementia cases. LBD and AD overlap in 25% of dementia cases.33 In patients older than 85 years, the prevalence jumps to 5% of the general population and 22% of all cases of dementia.33 Despite its prevalence, a recent study showed that only 6% of PCPs correctly identified LBD as the primary diagnosis when presented with typical case examples.32

Continue to: 3 stages of presentation

3 stages of presentation. Unlike other forms of dementia, LBD typically presents first with psychiatric symptoms, then with cognitive impairment, and last with parkinsonian symptoms. Additionally, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and often subtle elements of nonmemory cognitive impairment distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia.32 The primary cognitive deficit in LBD is not in memory but in attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability.34 Only in the later stages of the disease do patients exhibit gradual and progressive memory loss.

Mistaken for many things. When evaluating patients exhibiting signs of dementia, it’s important to include LBD in the differential, with increased suspicion for patients experiencing episodes of psychosis or delirium. The uniqueness of LBD lies in its psychotic symptomatology, particularly during earlier stages of the disease. This feature helps distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia. As seen in the case, LBD can also be confused with acute delirium.

Older adult patients presenting to the ED or clinic with visual hallucinations, delirium, and mental confusion may receive a false diagnosis of schizophrenia, medication- or substance-induced psychosis, Parkinson disease, or delirium of unknown etiology.35 Unfortunately, LBD is often overlooked and not considered in the differential diagnosis. Due to underrecognition, patients may receive treatment with typical antipsychotics. The addition of a neuroleptic to help control the psychotic symptoms causes patients with LBD to develop severe extrapyramidal symptoms and worsening mental status,36 leading to severe parkinsonian signs, which further muddies the diagnostic process. In addition, treatment for suspected Parkinson disease, including carbidopa-levodopa, has no benefit for patients with LBD and may increase psychotic symptoms.37

First-line treatment for LBD includes psychoeducation for the patient and family, cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, rivastigmine), and avoidance of high-potency antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. Although persistent hallucinations and psychosis remain difficult to treat in LBD, low-dose quetiapine is 1 option. Incorrectly diagnosing and prescribing treatment for another condition exacerbates symptoms in this patient population.

The patient has been experiencing chronic pain for the past few years after a motor vehicle accident. She has seen a physiatrist and another provider, both of whom found no “objective” causes of her chronic pain. They started the patient on sertraline for depression and an analgesic, both of which were ineffective.

The patient likes to exercise at a gym twice a week by doing light cardio (treadmill) exercise and light weightlifting. Lately, however, she has been unable to exercise due to the pain. At this visit, she mentions having low energy, poor sleep, frequent fatigue, and generalized soreness and pain in multiple areas of her body. The PCP recognizes the patient’s presenting symptoms as significant for FM and starts her on pregabalin and hydrotherapy, with positive results.

Continue to: Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

FM, the second most common disorder seen in rheumatologic practice after OA, is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 20 patients (approximately 5 million Americans) in the primary care setting.38,39 The condition has a high female-to-male preponderance (3.4% vs 0.5%).40 While the primary symptom of FM is chronic pain, patients commonly present with fatigue and sleep disturbance.41 Comorbid conditions include headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and mood disturbances (most commonly anxiety and depression).

Several studies have explored reasons for the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of FM. One important factor is ongoing skepticism among some physicians and the public, in general, as to whether FM is a real disease. This issue was addressed by a study by White and colleagues,42 who estimated and compared the point prevalence of FM and related disorders in Amish vs non-Amish adults. The authors hypothesized that if litigation and/or compensation availability have a major impact on FM prevalence, then there would be a near zero prevalence of FM in the Amish community. And yet, researchers found an overall age- and sex-adjusted FM prevalence of 7.3% (95% CI; 5.3%-9.7%); this was both statistically greater than zero (P < .0001) and greater than 2 control populations of non-Amish adults (both P < .05).

Many physicians consider FM fundamentally an emotional disturbance, and the high preponderance of FM in female patients may contribute to this misconception as reports of pain and emotional distress by women are often dismissed as hysteria.43 Physicians often explore the emotional aspects of FM, incorrectly diagnosing patients with depression and subsequently treating them with a psychotropic drug.39 Alternatively, they may focus on the musculoskeletal presentations of FM and prescribe analgesics or physical therapy, both of which do little to alleviate FM.

To make the correct diagnosis of FM, the American College of Rheumatology created a specific set of criteria in 1990, which was updated in 2010.44 For a diagnosis of FM, a patient must have at least a 3-month history of bilateral pain above and below the waist and along the axial skeletal spine. Although not included in the updated 2010 criteria, many clinicians continue to check for tender points, following the 1990 criteria requiring the presence of 11 of 18 points to make the diagnosis.

At least 3 cognitive biases relating to FM apply: anchoring, availability, and fundamental attribution error (see table 3).7 Anchoring occurs when the PCP settles on a psychiatric diagnosis of exaggerated pain syndrome, muscle overuse, or OA and fails to explore alternative etiology. Availability bias may obscure the true diagnosis of FM. Since PCPs see many patients with RA or OA, they may overlook or dismiss the possibility of FM. Attribution error happens when physicians dismiss the complaints of patients with FM as merely due to psychological distress, hysteria, or acting out.43

Patients with FM, who are often otherwise healthy, often present multiple times to the same PCP with a chief complaint of chronic pain. These repeat presentations can result in compassion fatigue and impact care. As Aloush and colleagues40 noted in their study, “FM patients were perceived as more difficult than RA patients, with a high level of concern and emotional response. A high proportion of physicians were reluctant to accept them because they feel emotional/psychological difficulties meeting and coping with these patients.”In response, patients with undiagnosed FM or inadequately treated FM may visit other PCPs, which may or may not result in a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We can do better

Primary care physicians face the daunting task of diagnosing and treating a wide range of common conditions while also trying to recognize less-common conditions with atypical presentations—all during a busy clinic workday. Nonetheless, we should strive to overcome internal (eg, cognitive bias and fund-of-knowledge deficits) and external (eg, time constraints, limited resources) pressures to improve diagnostic accuracy and care.

Each of the 4 disease states we’ve discussed have high rates of missed and/or delayed diagnosis. Each presents a unique set of confounders: PMR with its overlapping symptoms of many other rheumatologic diseases; OC with its often vague and misleading GI symptomatology; LBD with overlapping features of AD and Parkinson disease; and FM with skepticism. As gatekeepers to health care, it falls on PCPs to sort out these diagnostic dilemmas to avoid medical errors. Fundamental knowledge of each disease, its unique pathophysiology and symptoms, and varying presentations can be learned, internalized, and subsequently put into clinical practice to improve patient outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul D. Rosen MD, Brooklyn Hospital Center, Department of Family Medicine, 121 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11201; [email protected]

Medical errors in all settings contributed to as many as 250,000 deaths per year in the United States between 2000 and 2008, according to a 2016 study.1 Diagnostic error, in particular, remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide. In 2017, 12 million patients (roughly 5% of all US adults) who sought outpatient care experienced missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis at least once.2

In his classic work, How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, explored the diagnostic process with a focus on the role of cognitive bias in clinical decision-making. Groopman examined how physicians can become sidetracked in their thinking and “blinded” to potential alternative diagnoses.3 Medical error is not necessarily because of a deficiency in medical knowledge; rather, physicians become susceptible to medical error when defective and faulty reasoning distort their diagnostic ability.4

Cognitive bias in the diagnostic process has been extensively studied, and a full review is beyond the scope of this article.5 However, here we will examine pathways leading to diagnostic errors in the primary care setting, specifically the role of cognitive bias in the work-up of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), ovarian cancer (OC), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and fibromyalgia (FM). As these 4 disease states are seen with low-to-moderate frequency in primary care, cognitive bias can complicate accurate diagnosis. But first, a word about how to understand clinical reasoning.

There are 2 types of reasoning (and 1 is more prone to error)

Physician clinical reasoning can be divided into 2 different cognitive approaches.

Type 1 reasoning employs intuition and heuristics; this type is automatic, reflexive, and quick.5 While the use of mental shortcuts in type 1 increases the speed with which decisions are made, it also makes this form of reasoning more prone to error.

Type 2 reasoning requires conscious effort. It is goal directed and rigorous and therefore slower than type 1 reasoning. Extrapolated to the clinical context, clinicians transition from type 2 to type 1 reasoning as they gain experience and training throughout their careers and develop their own conscious and subconscious heuristics. Deviations from accurate decision-making occur in a systematic manner due to cognitive biases and result in medical error.6table 17 lists common types of cognitive bias.

An important question to ask. Physicians tend to fall into a pattern of quick, type 1 reasoning. However, it’s important to strive to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and avoid premature closure of the diagnostic process. It’s critical that we consider alternative diagnoses (ie, consciously move from type 1 to type 2 thinking) and continue to ask ourselves, “What else?” while working through differential diagnoses. This can be a powerful debiasing technique.

Continue to: The discussion...

The discussion of the following 4 disease states demonstrates how cognitive bias can lead to diagnostic error.

The patient is barely able to ambulate and appears to be in considerable pain. She is relying heavily on her walker and is assisted by her granddaughter. The primary care physician (PCP) obtains a detailed history that includes chronic shoulder and hip pain. Given that the patient has not responded to NSAID treatment over the previous 6 months, the PCP takes a moment to reconsider the diagnosis of OA and considers other options.

In light of the high prevalence of PMR in older women, the physician pursues a more specific physical examination tailored to ferret out PMR. He had learned this diagnostic shortcut as a resident, remembered it, and adeptly applied it whenever circumstances warranted. He asks the patient to raise her arms above her head (goalpost sign). She is unable to perform this task and experiences severe bilateral shoulder pain on trial. The PCP then places the patient on the examining table and attempts to assist her in rolling toward him. The patient is also unable to perform this maneuver and experiences significant bilateral hip pain on trial.

Based primarily on the patient’s history and physical exam findings, the PCP makes a presumptive diagnosis of PMR vs OA vs combined PMR with OA, orders an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and basic rheumatologic

PMR can be mistaken for OA

PMR is the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease in older patients.8 It is a debilitating illness with simple, effective treatment but has devastating consequences if missed or left untreated.9 PMR typically manifests in patients older than age 50, with a peak incidence at 80 years of age. It is also far more common in women.10

Approximately 80% of patients with PMR initially present to their PCP, often posing a diagnostic challenge to many clinicians.11 Due to overlap in symptoms, the condition is often misdiagnosed as OA, a more common condition seen by PCPs. Also, there are no specific diagnostic tests for PMR. An elevated ESR can help confirm the diagnosis, but one-third of patients with PMR have a normal ESR.12 Therefore, the diagnostic conundrum the physician faces is OA vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PMR, or another condition.

Continue to: The consequences...

The consequences of a missed and delayed PMR diagnosis range from seriously impaired quality of life to significantly increased risk of vascular events (eg, blindness, stroke) due to temporal arteritis.13 Early diagnosis is even more critical as the risk of a vascular event and death is highest during initial phases of the disease course.14

FPs often miss this Dx. A timely diagnosis relies almost exclusively on an accurate, thorough history and physical exam. However, PCPs often struggle to correctly diagnose PMR. According to a study by Bahlas and colleagues,15 the accuracy rate for correctly diagnosing PMR was 24% among a cohort of family physicians.

The differential diagnosis for PMR is broad and includes seronegative spondyloarthropathies, malignancy, Lyme disease, hypothyroidism, and both RA and OA.16

PCPs are extremely adept at correctly diagnosing RA, but not PMR. A study by Blaauw and colleagues17 comparing PCPs and rheumatologists found PCPs correctly identified 92% of RA cases but only 55% of PMR cases. When rheumatologists reviewed these same cases, they correctly identified PMR and RA almost 100% of the time.17 The difference in diagnostic accuracy between rheumatologists and PCPs suggests limited experience and gaps in fund of knowledge.

Making the diagnosis. The diagnosis of PMR is often made on empiric response to corticosteroid treatment, but doing so based solely on a patient’s response is controversial.18 There are rare instances in which patients with PMR fail to respond to treatment. On the other hand, some inflammatory conditions that mimic or share symptoms with PMR also respond to corticosteroids, potentially resulting in erroneous confirmation bias.

Some classification criteria use rapid response to low-dose prednisone/prednisolone (≤ 20 mg) to confirm the diagnosis,19 while other more recent guidelines no longer include this approach.20 If PMR continues to be suspected after a trial of steroids is unsuccessful, the PCP can try another course of higher dose steroids or consult with Rheumatology.

Continue to: A full history...

A full history and physical exam revealed a myriad of gastrointestinal (GI) complaints, such as diarrhea. But the PCP recalled a recent roundtable discussion on debiasing techniques specifically related to gynecologic disorders, including OC. Therefore, he decided to include OC in the differential diagnosis—something he would not routinely have done given the preponderance of GI symptoms. Despite the patient’s reluctance and time constraints, the PCP ordered a transvaginal ultrasound. Findings from the ultrasound study revealed stage II OC, which carries a good prognosis. The patient is currently undergoing treatment and was last reported as doing well.

Early signs of ovarian cancer can be chalked up to a “GI issue”

OC is the second most common gynecologic cancer21 and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death22 in US women. Compared to other cancers, the prognosis for localized early-stage OC is surprisingly good, with a 5-year survival rate approaching 93%.23 However, most disease is detected in later stages, and the 5-year survival rate drops to a low of 29%.24

There remains no established screening protocol for OC. Fewer than a quarter of all cases are diagnosed in stage I, and detection of OC relies heavily on the physician’s ability to decipher vague symptomatology that overlaps with other, more common maladies. This poses an obvious diagnostic challenge and, not surprisingly, a high level of susceptibility to cognitive bias.

More than 90% of patients with OC present with some combination of the following symptoms prior to diagnosis: abdominal (77%), GI (70%), pain (58%), constitutional (50%), urinary (34%), and pelvic (26%).25 The 3 most common isolated symptoms in patients with OC are abdominal bloating, decrease in appetite, and frank abdominal pain.26 Patients with biopsy-confirmed OC experience these symptoms an average of 6 months prior to actual diagnosis.27

Knowledge gaps play a role. Studies assessing the ability of health care providers to identify presenting symptoms of OC reveal specific knowledge gaps. For instance, in a survey by Gajjar and colleagues,28 most PCPs correctly identified bloating as a key symptom of OC; however, they weren’t as good at identifying less common symptoms, such as inability to finish a meal and early satiety. Moreover, survey participants misinterpreted or missed GI symptoms as an important manifestation of early OC disease.28 These specific knowledge gaps combine with physician errors in thinking, further obscuring and extending the diagnostic process. The point prevalence for OC is relatively low, and many PCPs only encounter a few cases during their entire career.29 This low pre-test probability may also fuel the delay in diagnosis.

Watch for these forms of bias. Since nonspecific symptoms of early-stage OC resemble those of other more benign conditions, a form of anchoring error known as multiple alternatives bias can arise. In this scenario, clinicians investigate only 1 potential plausible diagnosis and remain focused on that single, often faulty, conclusion. This persists despite other equally plausible alternatives that arise as the investigation proceeds.28

Affective error may also play a role in missed or delayed diagnosis. For example, a physician would prefer to diagnose and treat a common GI illness than consider OC. Another distortion involves outcome bias wherein the physician gives more significance to benign conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome because they have a more favorable outcome and clear treatment path. Physicians also favor these benign conditions because they encounter them more frequently than OC in the clinic setting. (This is known as availability bias.) Outcome bias and multiple alternatives bias can result in noninvestigation of symptoms and inefficient or improper management, leading to a delay in arriving at the correct diagnosis or anchoring on a plausible but incorrect diagnosis.

Continue to: An incorrect initial diagnostic...

An incorrect initial diagnostic path often triggers a cascade of subsequent errors. The physician orders additional unhelpful and expensive tests in an effort to characterize the suspected GI pathology. This then leads the physician to prematurely terminate the work-up and accept the most favored diagnosis. Lastly, sunk-cost fallacy comes into play: The physician has “invested” time and energy investigating a particular diagnosis and rather than abandon the presumed diagnosis, continues to put more time and effort in going down an incorrect diagnostic path.

A series of failures. These biases and miscues have been observed in several studies. For example, a survey of 1725 women by Goff and colleagues30 sought to identify factors related to delayed OC diagnosis. The authors found that the following factors were significantly associated with a delayed diagnosis: omission of a pelvic exam at initial presentation, a separate exploration of a multitude of collateral symptoms, a failure to order ultrasound/computed tomography/CA-125 test, and a failure to consider age as a factor (especially if the patient was outside the norm).

Responses from the survey also revealed that physicians initially ordered work-ups related to GI etiology and only later considered a pelvic work-up. This suggests that well-known presenting signs and symptoms or a constellation of typical and atypical symptoms of OC often failed to trigger physician recognition. Understandably, patients presenting with menorrhagia or gynecologic complaints are more likely to have OC detected at an earlier stage than patients who present with GI or abdominal signs alone.31 table 27 summarizes some of the cognitive biases seen in the diagnostic path of OC.

While in the hospital, he becomes acutely upset by the hallucinations and is given haloperidol and lorazepam by house staff. In the morning, the patient exhibits severe signs of Parkinson disease that include rigidity and masked facies.

Given the patient’s poor response to haloperidol and continued confusion, the team consulted Neurology and Psychiatry. Gathering a more detailed history from the patient and family, the patient is given a diagnosis of classic LBD. The antipsychotic medications are stopped. The patient and his family receive education about LBD treatment and management, and the patient is discharged to outpatient care.

Psychiatric symptoms can be an early “misdirect” in cases of Lewy body disease

LBD, the second leading neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD), affects 1.5 million Americans,32 representing about 10% of all dementia cases. LBD and AD overlap in 25% of dementia cases.33 In patients older than 85 years, the prevalence jumps to 5% of the general population and 22% of all cases of dementia.33 Despite its prevalence, a recent study showed that only 6% of PCPs correctly identified LBD as the primary diagnosis when presented with typical case examples.32

Continue to: 3 stages of presentation

3 stages of presentation. Unlike other forms of dementia, LBD typically presents first with psychiatric symptoms, then with cognitive impairment, and last with parkinsonian symptoms. Additionally, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and often subtle elements of nonmemory cognitive impairment distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia.32 The primary cognitive deficit in LBD is not in memory but in attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability.34 Only in the later stages of the disease do patients exhibit gradual and progressive memory loss.

Mistaken for many things. When evaluating patients exhibiting signs of dementia, it’s important to include LBD in the differential, with increased suspicion for patients experiencing episodes of psychosis or delirium. The uniqueness of LBD lies in its psychotic symptomatology, particularly during earlier stages of the disease. This feature helps distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia. As seen in the case, LBD can also be confused with acute delirium.

Older adult patients presenting to the ED or clinic with visual hallucinations, delirium, and mental confusion may receive a false diagnosis of schizophrenia, medication- or substance-induced psychosis, Parkinson disease, or delirium of unknown etiology.35 Unfortunately, LBD is often overlooked and not considered in the differential diagnosis. Due to underrecognition, patients may receive treatment with typical antipsychotics. The addition of a neuroleptic to help control the psychotic symptoms causes patients with LBD to develop severe extrapyramidal symptoms and worsening mental status,36 leading to severe parkinsonian signs, which further muddies the diagnostic process. In addition, treatment for suspected Parkinson disease, including carbidopa-levodopa, has no benefit for patients with LBD and may increase psychotic symptoms.37

First-line treatment for LBD includes psychoeducation for the patient and family, cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, rivastigmine), and avoidance of high-potency antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. Although persistent hallucinations and psychosis remain difficult to treat in LBD, low-dose quetiapine is 1 option. Incorrectly diagnosing and prescribing treatment for another condition exacerbates symptoms in this patient population.

The patient has been experiencing chronic pain for the past few years after a motor vehicle accident. She has seen a physiatrist and another provider, both of whom found no “objective” causes of her chronic pain. They started the patient on sertraline for depression and an analgesic, both of which were ineffective.

The patient likes to exercise at a gym twice a week by doing light cardio (treadmill) exercise and light weightlifting. Lately, however, she has been unable to exercise due to the pain. At this visit, she mentions having low energy, poor sleep, frequent fatigue, and generalized soreness and pain in multiple areas of her body. The PCP recognizes the patient’s presenting symptoms as significant for FM and starts her on pregabalin and hydrotherapy, with positive results.

Continue to: Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

FM, the second most common disorder seen in rheumatologic practice after OA, is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 20 patients (approximately 5 million Americans) in the primary care setting.38,39 The condition has a high female-to-male preponderance (3.4% vs 0.5%).40 While the primary symptom of FM is chronic pain, patients commonly present with fatigue and sleep disturbance.41 Comorbid conditions include headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and mood disturbances (most commonly anxiety and depression).

Several studies have explored reasons for the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of FM. One important factor is ongoing skepticism among some physicians and the public, in general, as to whether FM is a real disease. This issue was addressed by a study by White and colleagues,42 who estimated and compared the point prevalence of FM and related disorders in Amish vs non-Amish adults. The authors hypothesized that if litigation and/or compensation availability have a major impact on FM prevalence, then there would be a near zero prevalence of FM in the Amish community. And yet, researchers found an overall age- and sex-adjusted FM prevalence of 7.3% (95% CI; 5.3%-9.7%); this was both statistically greater than zero (P < .0001) and greater than 2 control populations of non-Amish adults (both P < .05).

Many physicians consider FM fundamentally an emotional disturbance, and the high preponderance of FM in female patients may contribute to this misconception as reports of pain and emotional distress by women are often dismissed as hysteria.43 Physicians often explore the emotional aspects of FM, incorrectly diagnosing patients with depression and subsequently treating them with a psychotropic drug.39 Alternatively, they may focus on the musculoskeletal presentations of FM and prescribe analgesics or physical therapy, both of which do little to alleviate FM.

To make the correct diagnosis of FM, the American College of Rheumatology created a specific set of criteria in 1990, which was updated in 2010.44 For a diagnosis of FM, a patient must have at least a 3-month history of bilateral pain above and below the waist and along the axial skeletal spine. Although not included in the updated 2010 criteria, many clinicians continue to check for tender points, following the 1990 criteria requiring the presence of 11 of 18 points to make the diagnosis.

At least 3 cognitive biases relating to FM apply: anchoring, availability, and fundamental attribution error (see table 3).7 Anchoring occurs when the PCP settles on a psychiatric diagnosis of exaggerated pain syndrome, muscle overuse, or OA and fails to explore alternative etiology. Availability bias may obscure the true diagnosis of FM. Since PCPs see many patients with RA or OA, they may overlook or dismiss the possibility of FM. Attribution error happens when physicians dismiss the complaints of patients with FM as merely due to psychological distress, hysteria, or acting out.43

Patients with FM, who are often otherwise healthy, often present multiple times to the same PCP with a chief complaint of chronic pain. These repeat presentations can result in compassion fatigue and impact care. As Aloush and colleagues40 noted in their study, “FM patients were perceived as more difficult than RA patients, with a high level of concern and emotional response. A high proportion of physicians were reluctant to accept them because they feel emotional/psychological difficulties meeting and coping with these patients.”In response, patients with undiagnosed FM or inadequately treated FM may visit other PCPs, which may or may not result in a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We can do better

Primary care physicians face the daunting task of diagnosing and treating a wide range of common conditions while also trying to recognize less-common conditions with atypical presentations—all during a busy clinic workday. Nonetheless, we should strive to overcome internal (eg, cognitive bias and fund-of-knowledge deficits) and external (eg, time constraints, limited resources) pressures to improve diagnostic accuracy and care.

Each of the 4 disease states we’ve discussed have high rates of missed and/or delayed diagnosis. Each presents a unique set of confounders: PMR with its overlapping symptoms of many other rheumatologic diseases; OC with its often vague and misleading GI symptomatology; LBD with overlapping features of AD and Parkinson disease; and FM with skepticism. As gatekeepers to health care, it falls on PCPs to sort out these diagnostic dilemmas to avoid medical errors. Fundamental knowledge of each disease, its unique pathophysiology and symptoms, and varying presentations can be learned, internalized, and subsequently put into clinical practice to improve patient outcomes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Paul D. Rosen MD, Brooklyn Hospital Center, Department of Family Medicine, 121 Dekalb Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11201; [email protected]

1. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139

2. Van Such M, Lohr R, Beckman T, et al. Extent of diagnostic agreement among medical referrals. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:870-874. doi: 10.1111/jep.12747

3. Groopman JE. How Doctors Think. Houghton Mifflin; 2007.

4. Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124-1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

5. Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, et al. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: Cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med. 2017;92:23-30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

6. Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775-780. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003

7. Morgenstern J. Cognitive errors in medicine: The common errors. First10EM blog. September 15, 2015. Updated September 22, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://first10em.com/cognitive-errors/

8. Gazitt T, Zisman D, Gardner G. Polymyalgia rheumatica: a common disease in seniors. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22:40. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00919-2

9. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176

10. Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, et al. Trends in the incidence of polymyalgia rheumatica over a 30 year period in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1694-1697.

11. Barraclough K, Liddell WG, du Toit J, et al. Polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: a cohort study of the diagnostic criteria and outcome. Fam Pract. 2008;25:328-33. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn044

12. Manzo C. Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) with normal values of both erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration at the time of diagnosis in a centenarian man: a case report. Diseases. 2018;6:84. doi: 10.3390/diseases6040084

13. Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Contemporary prevalence estimates for giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica, 2015. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:253-256. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.04.001

14. Nordborg E, Bengtsson BA. Death rates and causes of death in 284 consecutive patients with giant cell arteritis confirmed by biopsy. BMJ. 1989;299:549-550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6698.549

15. Bahlas S, Ramos-Remus C, Davis P. Utilisation and costs of investigations, and accuracy of diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica by family physicians. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:278-280. doi: 10.1007/s100670070045

16. Brooks RC, McGee SR. Diagnostic dilemmas in polymyalgia rheumatica. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:162-168.

17. Blaauw AA, Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP, et al. Assessing clinical competence: recognition of case descriptions of rheumatic diseases by general practitioners. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:375-379. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/34.4.375

18. Mager DR. Polymylagia rheumatica: common disease, elusive diagnosis. Home Healthc Now. 2015;33:132-138. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000000199

19. Kermani TA, Warrington KJ. Polymyalgia rheumatica. Lancet. 381;63-72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60680-1. Published correction appears in Lancet. 20135;381:28.

20. Liew DF, Owen CE, Buchanan RR. Prescribing for polymyalgia rheumatica. Aust Prescr. 2018;41:14-19. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2018.001