User login

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

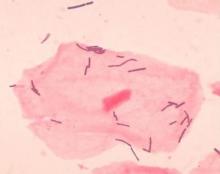

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE