User login

Ms. T, age 48, is brought to the psychiatric emergency department after the police find her walking along the highway at 3:00

Once involuntarily committed, does Ms. T have the right to refuse treatment?

Every psychiatrist has faced the predicament of a patient who refuses treatment. This creates an ethical dilemma between respecting the patient’s autonomy vs forcing treatment to ameliorate symptoms and reduce suffering. This article addresses case law related to the models for administering psychiatric medications over objection. We also discuss case law regarding court-appointed guardianship, and treating medical issues without consent. While this article provides valuable information on these scenarios, it is crucial to remember that the legal processes required to administer medications over patient objection are state-specific. In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, you must research the legal procedures specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

History of involuntary treatment

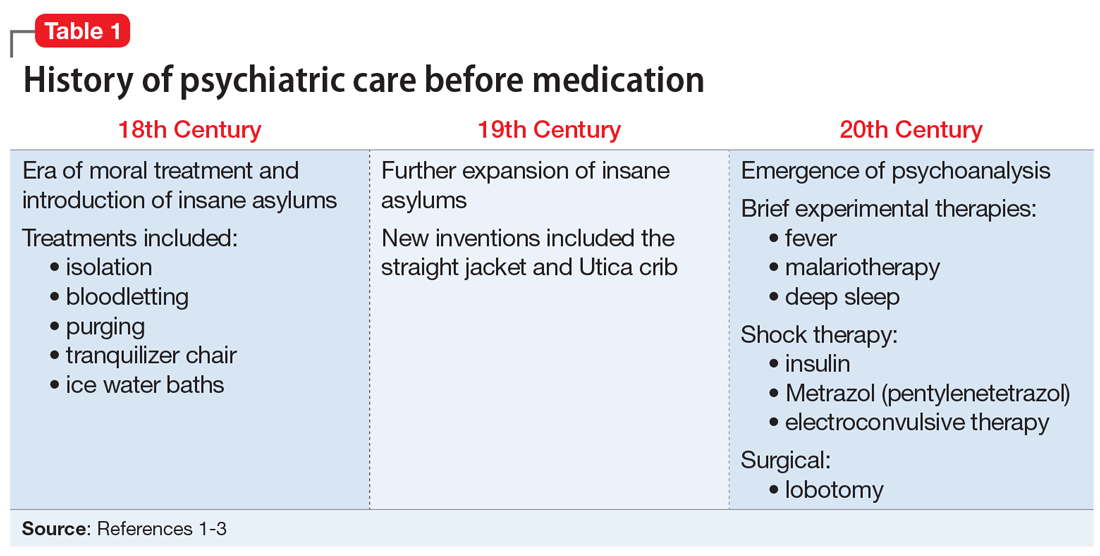

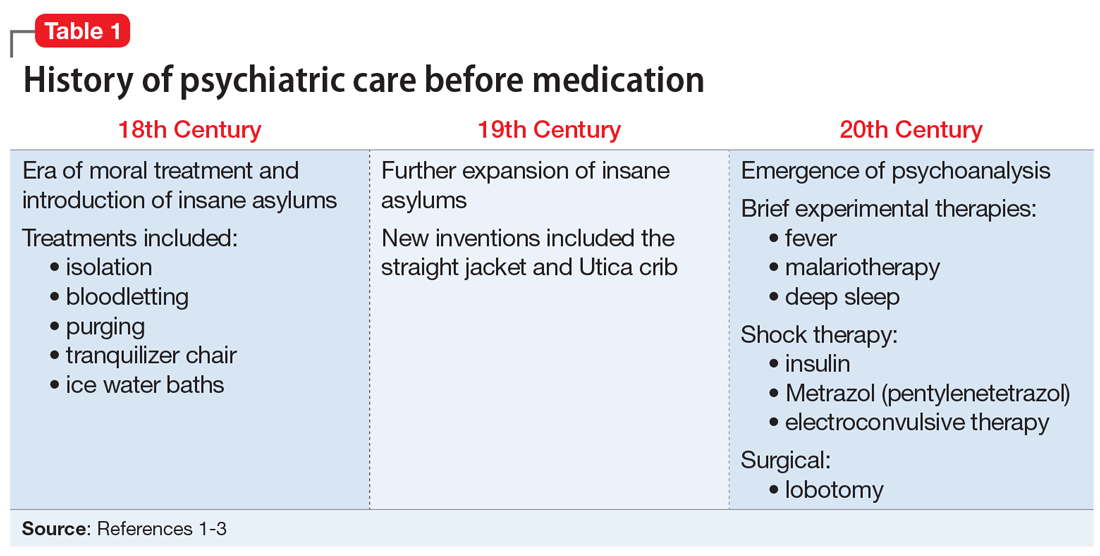

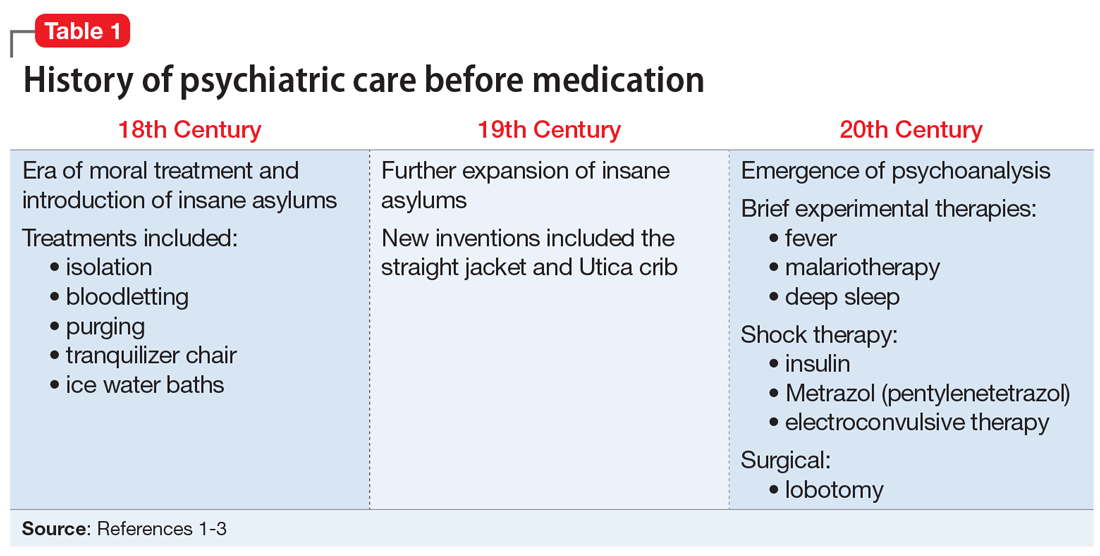

Prior to the 1960s, Ms. T would likely have been unable to refuse treatment. All patients were considered involuntary, and the course of treatment was decided solely by the psychiatric institution. Well into the 20th century, patients with psychiatric illness remained feared and stigmatized, which led to potent and potentially harsh methods of treatment. Some patients experienced extreme isolation, whipping, bloodletting, experimental use of chemicals, and starvation (Table 11-3).

With the advent of psychotropic medications and a focus on civil liberties, the psychiatric mindset began to change from hospital-based treatment to a community-based approach. The value of psychotherapy was recognized, and by the 1960s, the establishment of community mental health centers was gaining momentum.

In the context of these changes, the civil rights movement pressed for stronger legislation regarding autonomy and the quality of treatment available to patients with psychiatric illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rouse v Cameron4 and Wyatt v Stickney5 dealt with a patient’s right to receive treatment while involuntarily committed. However, it was not until the 1980s that the courts addressed the issue of a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

The judicial system: A primer

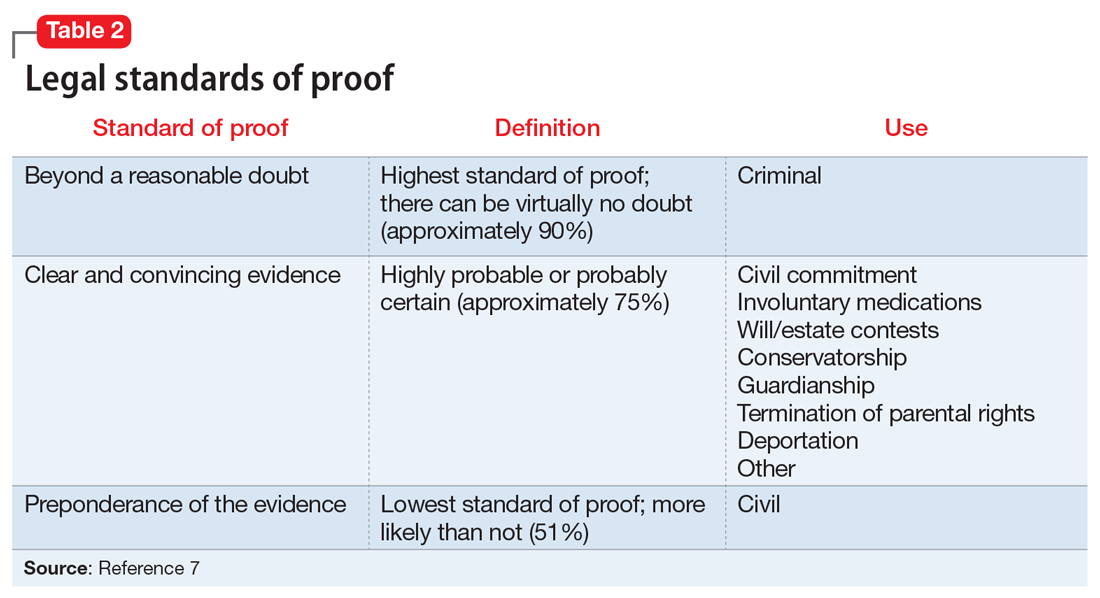

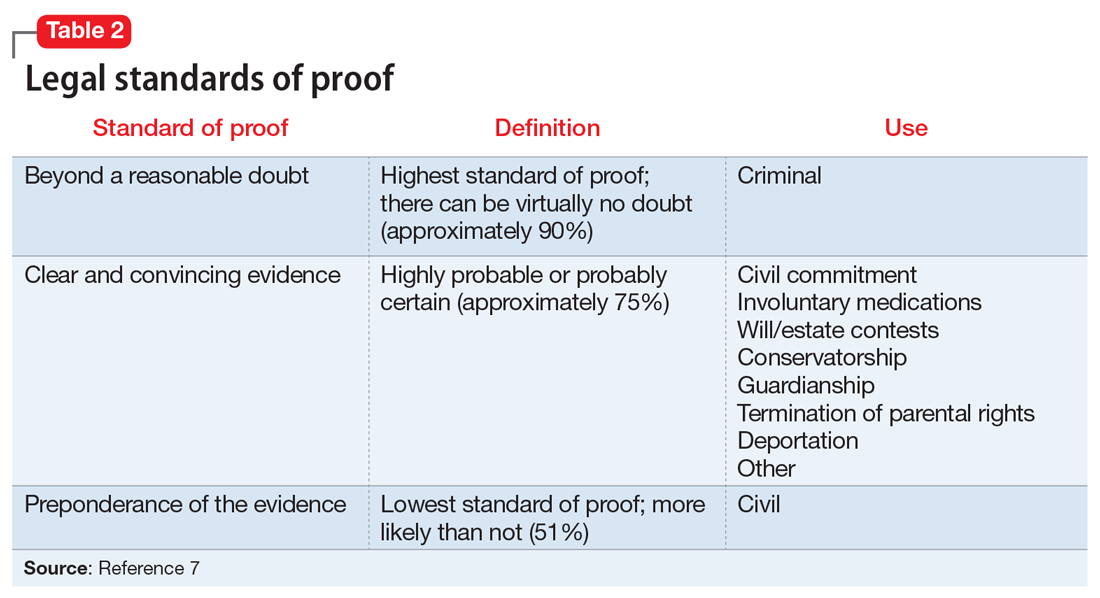

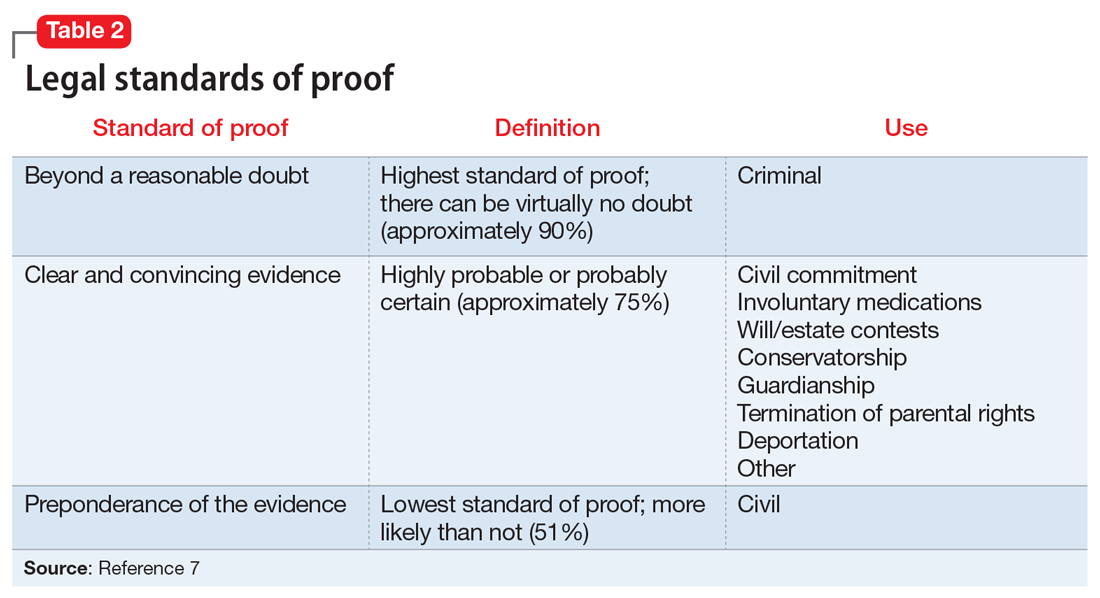

When reviewing case law and its applicability to your patients, it is important to understand the various court systems. The judicial system is divided into state and federal courts, which are subdivided into trial, appellate, and supreme courts. When decisions at either the state or federal level require an ultimate decision maker, the US Supreme Court can choose to hear the case, or grant certiorari, and make a ruling, which is then binding law.6 Decisions made by any court are based on various degrees of stringency, called standards of proof (Table 27).

Continue to: For Ms. T's case...

For Ms. T’s case, civil commitment and involuntary medication hearings are held in probate court, which is a civil (not criminal) court. In addition to overseeing civil commitment and involuntary medications, probate courts adjudicate will and estate contests, conservatorship, and guardianship. Conservatorship hearings deal with financial issues, and guardianship cases encompass personal and health-related needs. Regardless of the court, an individual is guaranteed due process under the 5th Amendment (federal) and 14th Amendment (state).

Individuals are presumed competent to make their own decisions, but a court may call this into question. Competencies are specific to a variety of areas, such as criminal proceedings, medical decision making, writing a will (testimonial capacity), etc. Because each field applies its own standard of competence, an individual may be competent in one area but incompetent in another. Competence in medical decision making varies by state but generally consists of being able to communicate a choice, understand relevant information, appreciate one’s illness and its likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information.8

Box

Administering medications despite a patient’s objection differs from situations in which medications are provided during a psychiatric emergency. In an emergency, courts do not have time to weigh in. Instead, emergency medications (most often given as IM injections) are administered based on the physician’s clinical judgment. The criteria for psychiatric emergencies are delineated at the state level, but typically are defined as when a person with a mental illness creates an imminent risk of harm to self or others. Alternative approaches to resolving the emergency may include verbal de-escalation, quiet time in a room devoid of stimuli, locked seclusion, or physical restraints. These measures are often exhausted before emergency medications are administered.

Source: Reference 9

It is important to note that the legal process required before administering involuntary medications is distinct from situations in which medication needs to be provided during a psychiatric emergency. The Box9 outlines the difference between these 2 scenarios.

4 Legal models

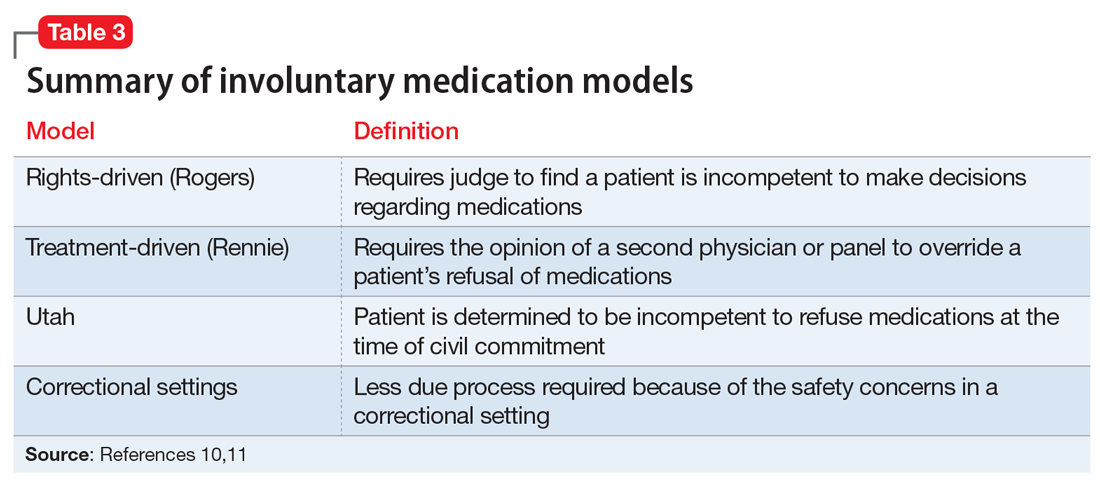

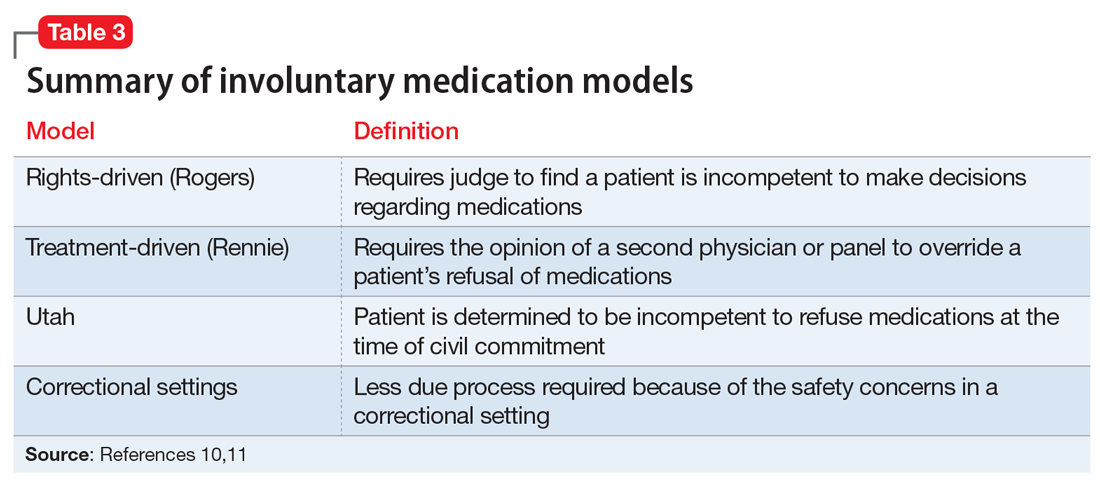

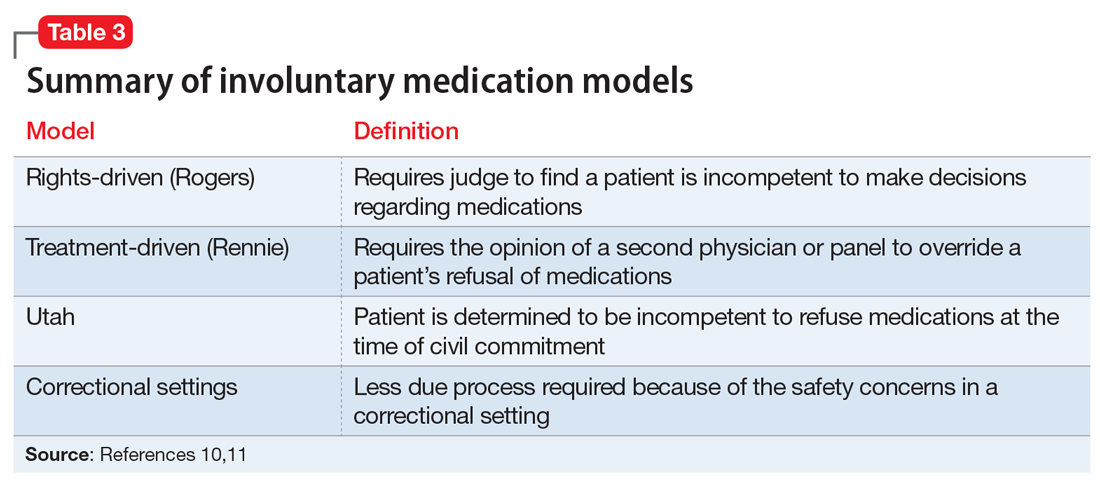

There are several legal models used to determine when a patient can be administered psychiatric medications over objection. Table 310,11 summarizes these models.

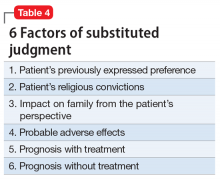

Rights-driven (Rogers) model. If Ms. T was involuntarily hospitalized in Massachusetts or another state that adopted the rights-driven model, she would retain the right to refuse treatment. These states require an external judicial review, and court approval is necessary before imposing any therapy. This model was established in Rogers v Commissioner,12 where 7 patients at the Boston State Hospital filed a lawsuit regarding their right to refuse medications. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, despite being involuntarily committed, a patient is considered competent to refuse treatment until found specifically incompetent to do so by the court. If a patient is found incompetent, the judge, using a full adversarial hearing, decides what the incompetent patient would have wanted if he/she were competent. The judge reaches a conclusion based on the substituted judgment model (Table 410). In Rogers v Commissioner,12 the court ruled that the right to decision making is not lost after becoming a patient at a mental health facility. The right is lost only if the patient is found incompetent by the judge. Thus, every individual has the right to “manage his own person” and “take care of himself.”

Continue to: An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model

An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model. Other states, such as Ohio, have adopted the Rogers model and addressed issues that arose subsequent to the aforementioned case. In Steele v Hamilton County,13 Jeffrey Steele was admitted and later civilly committed to the hospital. After 2 months, an involuntary medication hearing was completed in which 3 psychiatrists concluded that, although Mr. Steele was not a danger to himself or others while in the hospital, he would ultimately benefit from medications.

The probate court acknowledged that Mr. Steele lacked capacity and required hospitalization. However, because he was not imminently dangerous, medication should not be used involuntarily. After a series of appeals, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that a court may authorize the administration of an antipsychotic medication against a patient’s wishes without a finding of dangerousness when clear and convincing evidence exists that:

- the patient lacks the capacity to give or withhold informed consent regarding treatment

- the proposed medication is in the patient’s best interest

- no less intrusive treatment will be as effective in treating the mental illness.

This ruling set a precedent that dangerousness is not a requirement for involuntary medications.

Treatment-driven (Rennie) model. As in the rights-driven model, in the treatment-driven model, Ms. T would retain the constitutional right to refuse treatment. However, the models differ in the amount of procedural due process required. The treatment-driven model derives from Rennie v Klein,14 in which John Rennie, a patient at Ancora State Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey, filed a suit regarding the right of involuntarily committed patients to refuse antipsychotic medications. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that, if professional judgment deems a patient to be a danger to himself or others, then antipsychotics may be administered over individual objection. This professional judgment is typically based on the opinion of the treating physician, along with a second physician or panel.

Utah model. This model is based on A.E. and R.R. v Mitchell,15 in which the Utah District Court ruled that a civilly committed patient has no right to refuse treatment. This Utah model was created after state legislature determined that, in order to civilly commit a patient, hospitalization must be the least restrictive alternative and the patient is incompetent to consent to treatment. Unlike the 2 previous models, competency to refuse medications is not separated from a previous finding of civil commitment, but rather, they occur simultaneously.

Continue to: Rights in unique situations

Rights in unique situations

Correctional settings. If Ms. T was an inmate, would her right to refuse psychiatric medication change? This was addressed in the case of Washington v Harper.16 Walter Harper, serving time for a robbery conviction, filed a claim that his civil rights were being violated when he received involuntary medications based on the decision of a 3-person panel consisting of a psychiatrist, psychologist, and prison official. The US Supreme Court ruled that this process provided sufficient due process to mandate providing psychotropic medications against a patient’s will. This reduction in required procedures is related to the unique nature of the correctional environment and an increased need to maintain safety. This need was felt to outweigh an individual’s right to refuse medication.

Incompetent to stand trial. In Sell v U.S.,17 Charles Sell, a dentist, was charged with fraud and attempted murder. He underwent a competency evaluation and was found incompetent to stand trial because of delusional thinking. Mr. Sell was hospitalized for restorability but refused medications. The hospital held an administrative hearing to proceed with involuntary antipsychotic medications; however, Mr. Sell filed an order with the court to prevent this. Eventually, the US Supreme Court ruled that non-dangerous, incompetent defendants may be involuntarily medicated even if they do not pose a risk to self or others on the basis that it furthers the state’s interest in bringing to trial those charged with serious crimes. However, the following conditions must be met before involuntary medication can be administered:

- an important government issue must be at stake (determined case-by-case)

- a substantial probability must exist that the medication will enable the defendant to become competent without significant adverse effects

- the medication must be medically appropriate and necessary to restore competency, with no less restrictive alternative available.

This case suggests that, before one attempts to forcibly medicate a defendant for the purpose of competency restoration, one should exhaust the same judicial remedies one uses for civil patients first.

Court-appointed guardianship

In the case of Ms. T, what if her father requested to become her guardian? This question was explored in the matter of Guardianship of Richard Roe III.18 Mr. Roe was admitted to the Northampton State Hospital in Massachusetts, where he refused antipsychotic medications. Prior to his release, his father asked to be his guardian. The probate court obliged the request. However, Mr. Roe’s lawyer and guardian ad litem (a neutral temporary guardian often appointed when legal issues are pending) challenged the ruling, arguing the probate court cannot empower the guardian to consent to involuntary medication administration. On appeal, the court ruled:

- the guardianship was justified

- the standard of proof for establishment of a guardianship is preponderance of the evidence (Table 27)

- the guardian must seek from a court a “substituted judgment” to authorize forcible administration of antipsychotic medication.

The decision to establish the court as the final decision maker is based on the view that a patient’s relatives may be biased. Courts should take an objective approach that considers

- patient preference stated during periods of competency

- medication adverse effects

- consequences if treatment is refused

- prognosis with treatment

- religious beliefs

- impact on the patient’s family.

Continue to: This case set the stage for...

This case set the stage for later decisions that placed antipsychotic medications in the same category as electroconvulsive therapy and psychosurgery. This could mean a guardian would need specialized authorization to request antipsychotic treatment but could consent to an appendectomy without legal issue.

Fortunately, now most jurisdictions have remedied this cumbersome solution by requiring a higher standard of proof, clear and convincing evidence (Table 27), to establish guardianship but allowing the guardian more latitude to make decisions for their wards (such as those involving hospital admission or medications) without further court involvement.

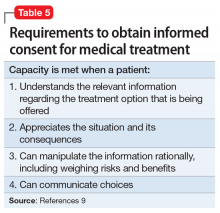

Involuntary medical treatment

In order for a patient to consent for medical treatment, he/she must have the capacity to do so (Table 59). How do the courts handle the patient’s right to refuse medical treatment? This was addressed in the case of Georgetown College v Jones.19 Mrs. Jones, a 25-year-old Jehovah’s Witness and mother of a 7-month-old baby, suffered a ruptured ulcer and lost a life-threatening amount of blood. Due to her religious beliefs, Mrs. Jones refused a blood transfusion. The hospital quickly appealed to the court, who ruled the woman was help-seeking by going to the hospital, did not want to die, was in distress, and lacked capacity to make medical decisions. Acting in a parens patriae manner (when the government steps in to make decisions for its citizens who cannot), the court ordered the hospital to administer blood transfusions.

Proxy decision maker. When the situation is less emergent, a proxy decision maker can be appointed by the court. This was addressed in the case of Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz.20 Mr. Saikewicz, a 67-year-old man with intellectual disability, was diagnosed with cancer and given weeks to months to live without treatment. However, treatment was only 50% effective and could potentially cause severe adverse effects. A guardian ad litem was appointed and recommended nontreatment, which the court upheld. The court ruled that the right to accept or reject medical treatment applies to both incompetent and competent persons. With incompetent persons, a “substituted judgment” analysis is used over the “best interest of the patient” doctrine.20 This falls in line with the Guardianship of Richard Roe III ruling,18 in which the court’s substituted judgment standard is enacted in an effort to respect patient autonomy.

Right to die. When does a patient have the right to die and what is the standard of proof? The US Supreme Court case Cruzan v Director21 addressed this. Nancy Cruzan was involved in a car crash, which left her in a persistent vegetative state with no significant cognitive function. She remained this way for 6 years before her parents sought to terminate life support. The hospital refused. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled that a standard of clear and convincing evidence (Table 27) is required to withdraw treatment, and in a 5-to-4 decision, the US Supreme Court upheld Missouri’s decision. This set the national standard for withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. The moderate standard of proof is based on the court’s ruling that the decision to terminate life is a particularly important one.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

After having been civilly committed to your inpatient psychiatric facility, Ms. T’s paranoia and disorganized behavior persist. She continues to refuse medications.

There are 3 options: respect her decision, negotiate with her, or attempt to force medications through due process.11 In negotiating a compromise, it is best to understand the barriers to treatment. A patient may refuse medications due to poor insight into his/her illness, medication adverse effects, a preference for an alternative treatment, delusional concerns over contamination and/or poisoning, interpersonal conflicts with the treatment staff, a preference for symptoms (eg, mania) over wellness, medication ineffectiveness, length of treatment course, or stigma.22,23 However, a patient’s unwillingness to compromise creates the dilemma of autonomy vs treatment.

For Ms. T, the treatment team felt initiating involuntary medication was the best option for her quality of life and safety. Because she resides in Ohio, a Rogers-like model was applied. The probate court was petitioned and found her incompetent to make medical decisions. The court accepted the physician’s recommendation of treatment with antipsychotic medications. If this scenario took place in New Jersey, a Rennie model would apply, requiring due process through the second opinion of another physician. Lastly, if Ms. T lived in Utah, she would have been unable to refuse medications once civilly committed.

Pros and cons of each model

Over the years, various concerns about each of these models have been raised. Given the slow-moving wheels of justice, one concern was that perhaps patients would be left “rotting with their rights on,” or lingering in a psychotic state out of respect for their civil liberties.19 While court hearings do not always happen quickly, more often than not, a judge will agree with the psychiatrist seeking treatment because the judge likely has little experience with mental illness and will defer to the physician’s expertise. This means the Rogers model may be more likely to produce the desired outcome, just more slowly. With respect to the Rennie model, although it is often more expeditious, the second opinion of an independent psychiatrist may contradict that of the original physician because the consultant will rely on his/her own expertise. Finally, some were concerned that psychiatrists would view the Utah model as carte blanche to start whatever medications they wanted with no respect for patient preference. Based on our clinical experience, none of these concerns have come to fruition over time, and patients safely receive medications over objection in hospitals every day.

Consider why the patient refuses medication

Regardless of which involuntary medication model is employed, it is important to consider the underlying cause for medication refusal, because it may affect future compliance. If the refusal is the result of a religious belief, history of adverse effects, or other rational motive, then it may be reasonable to respect the patient’s autonomy.24 However, if the refusal is secondary to symptoms of mental illness, it is appropriate to move forward with an involuntary medication hearing and treat the underlying condition.

Continue to: In the case of Ms. T...

In the case of Ms. T, she appeared to be refusing medications because of her psychotic symptoms, which could be effectively treated with antipsychotic medications. Therefore, Ms. T’s current lack of capacity is hopefully a transient phenomenon that can be ameliorated by initiating medication. Typically, antipsychotic medications begin to reduce psychotic symptoms within the first week, with further improvement over time.25 The value of the inpatient psychiatric setting is that it allows for daily monitoring of a patient’s response to treatment. As capacity is regained, patient autonomy over medical decisions is reinstated.

Bottom Line

The legal processes required to administer medications over a patient’s objection are state-specific, and multiple models are used. In general, a patient’s right to refuse treatment can be overruled by obtaining adjudication through the courts (Rogers model) or the opinion of a second physician (Rennie model). In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, research the legal procedure specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

Related Resources

- Miller D. Is forced treatment in our outpatients’ best interests? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/80277/forced-treatment-our-outpatients-best-interests.

- Miller D, Hanson A. Committed: The battle over involuntary psychiatric care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

1. Laffey P. Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1285-1297.

2. Porter R. Madness: a brief history. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2002.

3. Stetka B, Watson J. Odd and outlandish psychiatric treatments throughout history. Medscape Psychiatry. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/odd-psychiatric-treatments. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2020.

4. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

5. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

6. Administrative Office of the US Courts. Comparing federal and state Courts. United States Courts. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure/comparing-federal-state-courts. Accessed February 26, 2020.

7. Drogin E, Williams C. Introduction to the Legal System. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:80-83.

8. Appelbaum P, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

9. Kambam P. Informed consent and competence. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:115-121.

10. Wall B, Anfang S. Legal regulation of psychiatric treatment. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:306-333.

11. Pinals D, Nesbit A, Hoge S. Treatment refusal in psychiatric practice. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:155-163.

12. Rogers v Commissioner, 390 489 (Mass 1983).

13. Steele v Hamilton County, 90 Ohio St3d 176 (Ohio 2000).

14. Rennie v Klein, 462 F Supp 1131 (D NJ 1978).

15. AE and RR v Mitchell, 724 F.2d 864 (10th Cir 1983).

16. Washington v Harper, 494 US 210 (1990).

17. Sell v US, 539 US 166 (2003).

18. Guardianship of Richard Roe III, 383 415, 435 (Mass 1981).

19. Georgetown College v Jones, 331 F2d 1010 (DC Cir 1964).

20. Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz, 370 NE 2d 417 (1977).

21. Cruzan v Director, 497 US 261 (1990).

22. Owiti J, Bowers L. A literature review: refusal of psychotropic medication in acute inpatient psychiatric care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(7):637-647.

23. Appelbaum P, Gutheil T. “Rotting with their rights on”: constitutional theory and clinical reality in drug refusal by psychiatric patients. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1979;7(3):306-315.

24. Adelugba OO, Mela M, Haq IU. Psychotropic medication refusal: reasons and patients’ perception at a secure forensic psychiatric treatment centre. J Forensic Sci Med. 2016;2(1):12-17.

25. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228.

Ms. T, age 48, is brought to the psychiatric emergency department after the police find her walking along the highway at 3:00

Once involuntarily committed, does Ms. T have the right to refuse treatment?

Every psychiatrist has faced the predicament of a patient who refuses treatment. This creates an ethical dilemma between respecting the patient’s autonomy vs forcing treatment to ameliorate symptoms and reduce suffering. This article addresses case law related to the models for administering psychiatric medications over objection. We also discuss case law regarding court-appointed guardianship, and treating medical issues without consent. While this article provides valuable information on these scenarios, it is crucial to remember that the legal processes required to administer medications over patient objection are state-specific. In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, you must research the legal procedures specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

History of involuntary treatment

Prior to the 1960s, Ms. T would likely have been unable to refuse treatment. All patients were considered involuntary, and the course of treatment was decided solely by the psychiatric institution. Well into the 20th century, patients with psychiatric illness remained feared and stigmatized, which led to potent and potentially harsh methods of treatment. Some patients experienced extreme isolation, whipping, bloodletting, experimental use of chemicals, and starvation (Table 11-3).

With the advent of psychotropic medications and a focus on civil liberties, the psychiatric mindset began to change from hospital-based treatment to a community-based approach. The value of psychotherapy was recognized, and by the 1960s, the establishment of community mental health centers was gaining momentum.

In the context of these changes, the civil rights movement pressed for stronger legislation regarding autonomy and the quality of treatment available to patients with psychiatric illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rouse v Cameron4 and Wyatt v Stickney5 dealt with a patient’s right to receive treatment while involuntarily committed. However, it was not until the 1980s that the courts addressed the issue of a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

The judicial system: A primer

When reviewing case law and its applicability to your patients, it is important to understand the various court systems. The judicial system is divided into state and federal courts, which are subdivided into trial, appellate, and supreme courts. When decisions at either the state or federal level require an ultimate decision maker, the US Supreme Court can choose to hear the case, or grant certiorari, and make a ruling, which is then binding law.6 Decisions made by any court are based on various degrees of stringency, called standards of proof (Table 27).

Continue to: For Ms. T's case...

For Ms. T’s case, civil commitment and involuntary medication hearings are held in probate court, which is a civil (not criminal) court. In addition to overseeing civil commitment and involuntary medications, probate courts adjudicate will and estate contests, conservatorship, and guardianship. Conservatorship hearings deal with financial issues, and guardianship cases encompass personal and health-related needs. Regardless of the court, an individual is guaranteed due process under the 5th Amendment (federal) and 14th Amendment (state).

Individuals are presumed competent to make their own decisions, but a court may call this into question. Competencies are specific to a variety of areas, such as criminal proceedings, medical decision making, writing a will (testimonial capacity), etc. Because each field applies its own standard of competence, an individual may be competent in one area but incompetent in another. Competence in medical decision making varies by state but generally consists of being able to communicate a choice, understand relevant information, appreciate one’s illness and its likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information.8

Box

Administering medications despite a patient’s objection differs from situations in which medications are provided during a psychiatric emergency. In an emergency, courts do not have time to weigh in. Instead, emergency medications (most often given as IM injections) are administered based on the physician’s clinical judgment. The criteria for psychiatric emergencies are delineated at the state level, but typically are defined as when a person with a mental illness creates an imminent risk of harm to self or others. Alternative approaches to resolving the emergency may include verbal de-escalation, quiet time in a room devoid of stimuli, locked seclusion, or physical restraints. These measures are often exhausted before emergency medications are administered.

Source: Reference 9

It is important to note that the legal process required before administering involuntary medications is distinct from situations in which medication needs to be provided during a psychiatric emergency. The Box9 outlines the difference between these 2 scenarios.

4 Legal models

There are several legal models used to determine when a patient can be administered psychiatric medications over objection. Table 310,11 summarizes these models.

Rights-driven (Rogers) model. If Ms. T was involuntarily hospitalized in Massachusetts or another state that adopted the rights-driven model, she would retain the right to refuse treatment. These states require an external judicial review, and court approval is necessary before imposing any therapy. This model was established in Rogers v Commissioner,12 where 7 patients at the Boston State Hospital filed a lawsuit regarding their right to refuse medications. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, despite being involuntarily committed, a patient is considered competent to refuse treatment until found specifically incompetent to do so by the court. If a patient is found incompetent, the judge, using a full adversarial hearing, decides what the incompetent patient would have wanted if he/she were competent. The judge reaches a conclusion based on the substituted judgment model (Table 410). In Rogers v Commissioner,12 the court ruled that the right to decision making is not lost after becoming a patient at a mental health facility. The right is lost only if the patient is found incompetent by the judge. Thus, every individual has the right to “manage his own person” and “take care of himself.”

Continue to: An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model

An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model. Other states, such as Ohio, have adopted the Rogers model and addressed issues that arose subsequent to the aforementioned case. In Steele v Hamilton County,13 Jeffrey Steele was admitted and later civilly committed to the hospital. After 2 months, an involuntary medication hearing was completed in which 3 psychiatrists concluded that, although Mr. Steele was not a danger to himself or others while in the hospital, he would ultimately benefit from medications.

The probate court acknowledged that Mr. Steele lacked capacity and required hospitalization. However, because he was not imminently dangerous, medication should not be used involuntarily. After a series of appeals, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that a court may authorize the administration of an antipsychotic medication against a patient’s wishes without a finding of dangerousness when clear and convincing evidence exists that:

- the patient lacks the capacity to give or withhold informed consent regarding treatment

- the proposed medication is in the patient’s best interest

- no less intrusive treatment will be as effective in treating the mental illness.

This ruling set a precedent that dangerousness is not a requirement for involuntary medications.

Treatment-driven (Rennie) model. As in the rights-driven model, in the treatment-driven model, Ms. T would retain the constitutional right to refuse treatment. However, the models differ in the amount of procedural due process required. The treatment-driven model derives from Rennie v Klein,14 in which John Rennie, a patient at Ancora State Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey, filed a suit regarding the right of involuntarily committed patients to refuse antipsychotic medications. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that, if professional judgment deems a patient to be a danger to himself or others, then antipsychotics may be administered over individual objection. This professional judgment is typically based on the opinion of the treating physician, along with a second physician or panel.

Utah model. This model is based on A.E. and R.R. v Mitchell,15 in which the Utah District Court ruled that a civilly committed patient has no right to refuse treatment. This Utah model was created after state legislature determined that, in order to civilly commit a patient, hospitalization must be the least restrictive alternative and the patient is incompetent to consent to treatment. Unlike the 2 previous models, competency to refuse medications is not separated from a previous finding of civil commitment, but rather, they occur simultaneously.

Continue to: Rights in unique situations

Rights in unique situations

Correctional settings. If Ms. T was an inmate, would her right to refuse psychiatric medication change? This was addressed in the case of Washington v Harper.16 Walter Harper, serving time for a robbery conviction, filed a claim that his civil rights were being violated when he received involuntary medications based on the decision of a 3-person panel consisting of a psychiatrist, psychologist, and prison official. The US Supreme Court ruled that this process provided sufficient due process to mandate providing psychotropic medications against a patient’s will. This reduction in required procedures is related to the unique nature of the correctional environment and an increased need to maintain safety. This need was felt to outweigh an individual’s right to refuse medication.

Incompetent to stand trial. In Sell v U.S.,17 Charles Sell, a dentist, was charged with fraud and attempted murder. He underwent a competency evaluation and was found incompetent to stand trial because of delusional thinking. Mr. Sell was hospitalized for restorability but refused medications. The hospital held an administrative hearing to proceed with involuntary antipsychotic medications; however, Mr. Sell filed an order with the court to prevent this. Eventually, the US Supreme Court ruled that non-dangerous, incompetent defendants may be involuntarily medicated even if they do not pose a risk to self or others on the basis that it furthers the state’s interest in bringing to trial those charged with serious crimes. However, the following conditions must be met before involuntary medication can be administered:

- an important government issue must be at stake (determined case-by-case)

- a substantial probability must exist that the medication will enable the defendant to become competent without significant adverse effects

- the medication must be medically appropriate and necessary to restore competency, with no less restrictive alternative available.

This case suggests that, before one attempts to forcibly medicate a defendant for the purpose of competency restoration, one should exhaust the same judicial remedies one uses for civil patients first.

Court-appointed guardianship

In the case of Ms. T, what if her father requested to become her guardian? This question was explored in the matter of Guardianship of Richard Roe III.18 Mr. Roe was admitted to the Northampton State Hospital in Massachusetts, where he refused antipsychotic medications. Prior to his release, his father asked to be his guardian. The probate court obliged the request. However, Mr. Roe’s lawyer and guardian ad litem (a neutral temporary guardian often appointed when legal issues are pending) challenged the ruling, arguing the probate court cannot empower the guardian to consent to involuntary medication administration. On appeal, the court ruled:

- the guardianship was justified

- the standard of proof for establishment of a guardianship is preponderance of the evidence (Table 27)

- the guardian must seek from a court a “substituted judgment” to authorize forcible administration of antipsychotic medication.

The decision to establish the court as the final decision maker is based on the view that a patient’s relatives may be biased. Courts should take an objective approach that considers

- patient preference stated during periods of competency

- medication adverse effects

- consequences if treatment is refused

- prognosis with treatment

- religious beliefs

- impact on the patient’s family.

Continue to: This case set the stage for...

This case set the stage for later decisions that placed antipsychotic medications in the same category as electroconvulsive therapy and psychosurgery. This could mean a guardian would need specialized authorization to request antipsychotic treatment but could consent to an appendectomy without legal issue.

Fortunately, now most jurisdictions have remedied this cumbersome solution by requiring a higher standard of proof, clear and convincing evidence (Table 27), to establish guardianship but allowing the guardian more latitude to make decisions for their wards (such as those involving hospital admission or medications) without further court involvement.

Involuntary medical treatment

In order for a patient to consent for medical treatment, he/she must have the capacity to do so (Table 59). How do the courts handle the patient’s right to refuse medical treatment? This was addressed in the case of Georgetown College v Jones.19 Mrs. Jones, a 25-year-old Jehovah’s Witness and mother of a 7-month-old baby, suffered a ruptured ulcer and lost a life-threatening amount of blood. Due to her religious beliefs, Mrs. Jones refused a blood transfusion. The hospital quickly appealed to the court, who ruled the woman was help-seeking by going to the hospital, did not want to die, was in distress, and lacked capacity to make medical decisions. Acting in a parens patriae manner (when the government steps in to make decisions for its citizens who cannot), the court ordered the hospital to administer blood transfusions.

Proxy decision maker. When the situation is less emergent, a proxy decision maker can be appointed by the court. This was addressed in the case of Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz.20 Mr. Saikewicz, a 67-year-old man with intellectual disability, was diagnosed with cancer and given weeks to months to live without treatment. However, treatment was only 50% effective and could potentially cause severe adverse effects. A guardian ad litem was appointed and recommended nontreatment, which the court upheld. The court ruled that the right to accept or reject medical treatment applies to both incompetent and competent persons. With incompetent persons, a “substituted judgment” analysis is used over the “best interest of the patient” doctrine.20 This falls in line with the Guardianship of Richard Roe III ruling,18 in which the court’s substituted judgment standard is enacted in an effort to respect patient autonomy.

Right to die. When does a patient have the right to die and what is the standard of proof? The US Supreme Court case Cruzan v Director21 addressed this. Nancy Cruzan was involved in a car crash, which left her in a persistent vegetative state with no significant cognitive function. She remained this way for 6 years before her parents sought to terminate life support. The hospital refused. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled that a standard of clear and convincing evidence (Table 27) is required to withdraw treatment, and in a 5-to-4 decision, the US Supreme Court upheld Missouri’s decision. This set the national standard for withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. The moderate standard of proof is based on the court’s ruling that the decision to terminate life is a particularly important one.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

After having been civilly committed to your inpatient psychiatric facility, Ms. T’s paranoia and disorganized behavior persist. She continues to refuse medications.

There are 3 options: respect her decision, negotiate with her, or attempt to force medications through due process.11 In negotiating a compromise, it is best to understand the barriers to treatment. A patient may refuse medications due to poor insight into his/her illness, medication adverse effects, a preference for an alternative treatment, delusional concerns over contamination and/or poisoning, interpersonal conflicts with the treatment staff, a preference for symptoms (eg, mania) over wellness, medication ineffectiveness, length of treatment course, or stigma.22,23 However, a patient’s unwillingness to compromise creates the dilemma of autonomy vs treatment.

For Ms. T, the treatment team felt initiating involuntary medication was the best option for her quality of life and safety. Because she resides in Ohio, a Rogers-like model was applied. The probate court was petitioned and found her incompetent to make medical decisions. The court accepted the physician’s recommendation of treatment with antipsychotic medications. If this scenario took place in New Jersey, a Rennie model would apply, requiring due process through the second opinion of another physician. Lastly, if Ms. T lived in Utah, she would have been unable to refuse medications once civilly committed.

Pros and cons of each model

Over the years, various concerns about each of these models have been raised. Given the slow-moving wheels of justice, one concern was that perhaps patients would be left “rotting with their rights on,” or lingering in a psychotic state out of respect for their civil liberties.19 While court hearings do not always happen quickly, more often than not, a judge will agree with the psychiatrist seeking treatment because the judge likely has little experience with mental illness and will defer to the physician’s expertise. This means the Rogers model may be more likely to produce the desired outcome, just more slowly. With respect to the Rennie model, although it is often more expeditious, the second opinion of an independent psychiatrist may contradict that of the original physician because the consultant will rely on his/her own expertise. Finally, some were concerned that psychiatrists would view the Utah model as carte blanche to start whatever medications they wanted with no respect for patient preference. Based on our clinical experience, none of these concerns have come to fruition over time, and patients safely receive medications over objection in hospitals every day.

Consider why the patient refuses medication

Regardless of which involuntary medication model is employed, it is important to consider the underlying cause for medication refusal, because it may affect future compliance. If the refusal is the result of a religious belief, history of adverse effects, or other rational motive, then it may be reasonable to respect the patient’s autonomy.24 However, if the refusal is secondary to symptoms of mental illness, it is appropriate to move forward with an involuntary medication hearing and treat the underlying condition.

Continue to: In the case of Ms. T...

In the case of Ms. T, she appeared to be refusing medications because of her psychotic symptoms, which could be effectively treated with antipsychotic medications. Therefore, Ms. T’s current lack of capacity is hopefully a transient phenomenon that can be ameliorated by initiating medication. Typically, antipsychotic medications begin to reduce psychotic symptoms within the first week, with further improvement over time.25 The value of the inpatient psychiatric setting is that it allows for daily monitoring of a patient’s response to treatment. As capacity is regained, patient autonomy over medical decisions is reinstated.

Bottom Line

The legal processes required to administer medications over a patient’s objection are state-specific, and multiple models are used. In general, a patient’s right to refuse treatment can be overruled by obtaining adjudication through the courts (Rogers model) or the opinion of a second physician (Rennie model). In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, research the legal procedure specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

Related Resources

- Miller D. Is forced treatment in our outpatients’ best interests? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/80277/forced-treatment-our-outpatients-best-interests.

- Miller D, Hanson A. Committed: The battle over involuntary psychiatric care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

Ms. T, age 48, is brought to the psychiatric emergency department after the police find her walking along the highway at 3:00

Once involuntarily committed, does Ms. T have the right to refuse treatment?

Every psychiatrist has faced the predicament of a patient who refuses treatment. This creates an ethical dilemma between respecting the patient’s autonomy vs forcing treatment to ameliorate symptoms and reduce suffering. This article addresses case law related to the models for administering psychiatric medications over objection. We also discuss case law regarding court-appointed guardianship, and treating medical issues without consent. While this article provides valuable information on these scenarios, it is crucial to remember that the legal processes required to administer medications over patient objection are state-specific. In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, you must research the legal procedures specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

History of involuntary treatment

Prior to the 1960s, Ms. T would likely have been unable to refuse treatment. All patients were considered involuntary, and the course of treatment was decided solely by the psychiatric institution. Well into the 20th century, patients with psychiatric illness remained feared and stigmatized, which led to potent and potentially harsh methods of treatment. Some patients experienced extreme isolation, whipping, bloodletting, experimental use of chemicals, and starvation (Table 11-3).

With the advent of psychotropic medications and a focus on civil liberties, the psychiatric mindset began to change from hospital-based treatment to a community-based approach. The value of psychotherapy was recognized, and by the 1960s, the establishment of community mental health centers was gaining momentum.

In the context of these changes, the civil rights movement pressed for stronger legislation regarding autonomy and the quality of treatment available to patients with psychiatric illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rouse v Cameron4 and Wyatt v Stickney5 dealt with a patient’s right to receive treatment while involuntarily committed. However, it was not until the 1980s that the courts addressed the issue of a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

The judicial system: A primer

When reviewing case law and its applicability to your patients, it is important to understand the various court systems. The judicial system is divided into state and federal courts, which are subdivided into trial, appellate, and supreme courts. When decisions at either the state or federal level require an ultimate decision maker, the US Supreme Court can choose to hear the case, or grant certiorari, and make a ruling, which is then binding law.6 Decisions made by any court are based on various degrees of stringency, called standards of proof (Table 27).

Continue to: For Ms. T's case...

For Ms. T’s case, civil commitment and involuntary medication hearings are held in probate court, which is a civil (not criminal) court. In addition to overseeing civil commitment and involuntary medications, probate courts adjudicate will and estate contests, conservatorship, and guardianship. Conservatorship hearings deal with financial issues, and guardianship cases encompass personal and health-related needs. Regardless of the court, an individual is guaranteed due process under the 5th Amendment (federal) and 14th Amendment (state).

Individuals are presumed competent to make their own decisions, but a court may call this into question. Competencies are specific to a variety of areas, such as criminal proceedings, medical decision making, writing a will (testimonial capacity), etc. Because each field applies its own standard of competence, an individual may be competent in one area but incompetent in another. Competence in medical decision making varies by state but generally consists of being able to communicate a choice, understand relevant information, appreciate one’s illness and its likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information.8

Box

Administering medications despite a patient’s objection differs from situations in which medications are provided during a psychiatric emergency. In an emergency, courts do not have time to weigh in. Instead, emergency medications (most often given as IM injections) are administered based on the physician’s clinical judgment. The criteria for psychiatric emergencies are delineated at the state level, but typically are defined as when a person with a mental illness creates an imminent risk of harm to self or others. Alternative approaches to resolving the emergency may include verbal de-escalation, quiet time in a room devoid of stimuli, locked seclusion, or physical restraints. These measures are often exhausted before emergency medications are administered.

Source: Reference 9

It is important to note that the legal process required before administering involuntary medications is distinct from situations in which medication needs to be provided during a psychiatric emergency. The Box9 outlines the difference between these 2 scenarios.

4 Legal models

There are several legal models used to determine when a patient can be administered psychiatric medications over objection. Table 310,11 summarizes these models.

Rights-driven (Rogers) model. If Ms. T was involuntarily hospitalized in Massachusetts or another state that adopted the rights-driven model, she would retain the right to refuse treatment. These states require an external judicial review, and court approval is necessary before imposing any therapy. This model was established in Rogers v Commissioner,12 where 7 patients at the Boston State Hospital filed a lawsuit regarding their right to refuse medications. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, despite being involuntarily committed, a patient is considered competent to refuse treatment until found specifically incompetent to do so by the court. If a patient is found incompetent, the judge, using a full adversarial hearing, decides what the incompetent patient would have wanted if he/she were competent. The judge reaches a conclusion based on the substituted judgment model (Table 410). In Rogers v Commissioner,12 the court ruled that the right to decision making is not lost after becoming a patient at a mental health facility. The right is lost only if the patient is found incompetent by the judge. Thus, every individual has the right to “manage his own person” and “take care of himself.”

Continue to: An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model

An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model. Other states, such as Ohio, have adopted the Rogers model and addressed issues that arose subsequent to the aforementioned case. In Steele v Hamilton County,13 Jeffrey Steele was admitted and later civilly committed to the hospital. After 2 months, an involuntary medication hearing was completed in which 3 psychiatrists concluded that, although Mr. Steele was not a danger to himself or others while in the hospital, he would ultimately benefit from medications.

The probate court acknowledged that Mr. Steele lacked capacity and required hospitalization. However, because he was not imminently dangerous, medication should not be used involuntarily. After a series of appeals, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that a court may authorize the administration of an antipsychotic medication against a patient’s wishes without a finding of dangerousness when clear and convincing evidence exists that:

- the patient lacks the capacity to give or withhold informed consent regarding treatment

- the proposed medication is in the patient’s best interest

- no less intrusive treatment will be as effective in treating the mental illness.

This ruling set a precedent that dangerousness is not a requirement for involuntary medications.

Treatment-driven (Rennie) model. As in the rights-driven model, in the treatment-driven model, Ms. T would retain the constitutional right to refuse treatment. However, the models differ in the amount of procedural due process required. The treatment-driven model derives from Rennie v Klein,14 in which John Rennie, a patient at Ancora State Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey, filed a suit regarding the right of involuntarily committed patients to refuse antipsychotic medications. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that, if professional judgment deems a patient to be a danger to himself or others, then antipsychotics may be administered over individual objection. This professional judgment is typically based on the opinion of the treating physician, along with a second physician or panel.

Utah model. This model is based on A.E. and R.R. v Mitchell,15 in which the Utah District Court ruled that a civilly committed patient has no right to refuse treatment. This Utah model was created after state legislature determined that, in order to civilly commit a patient, hospitalization must be the least restrictive alternative and the patient is incompetent to consent to treatment. Unlike the 2 previous models, competency to refuse medications is not separated from a previous finding of civil commitment, but rather, they occur simultaneously.

Continue to: Rights in unique situations

Rights in unique situations

Correctional settings. If Ms. T was an inmate, would her right to refuse psychiatric medication change? This was addressed in the case of Washington v Harper.16 Walter Harper, serving time for a robbery conviction, filed a claim that his civil rights were being violated when he received involuntary medications based on the decision of a 3-person panel consisting of a psychiatrist, psychologist, and prison official. The US Supreme Court ruled that this process provided sufficient due process to mandate providing psychotropic medications against a patient’s will. This reduction in required procedures is related to the unique nature of the correctional environment and an increased need to maintain safety. This need was felt to outweigh an individual’s right to refuse medication.

Incompetent to stand trial. In Sell v U.S.,17 Charles Sell, a dentist, was charged with fraud and attempted murder. He underwent a competency evaluation and was found incompetent to stand trial because of delusional thinking. Mr. Sell was hospitalized for restorability but refused medications. The hospital held an administrative hearing to proceed with involuntary antipsychotic medications; however, Mr. Sell filed an order with the court to prevent this. Eventually, the US Supreme Court ruled that non-dangerous, incompetent defendants may be involuntarily medicated even if they do not pose a risk to self or others on the basis that it furthers the state’s interest in bringing to trial those charged with serious crimes. However, the following conditions must be met before involuntary medication can be administered:

- an important government issue must be at stake (determined case-by-case)

- a substantial probability must exist that the medication will enable the defendant to become competent without significant adverse effects

- the medication must be medically appropriate and necessary to restore competency, with no less restrictive alternative available.

This case suggests that, before one attempts to forcibly medicate a defendant for the purpose of competency restoration, one should exhaust the same judicial remedies one uses for civil patients first.

Court-appointed guardianship

In the case of Ms. T, what if her father requested to become her guardian? This question was explored in the matter of Guardianship of Richard Roe III.18 Mr. Roe was admitted to the Northampton State Hospital in Massachusetts, where he refused antipsychotic medications. Prior to his release, his father asked to be his guardian. The probate court obliged the request. However, Mr. Roe’s lawyer and guardian ad litem (a neutral temporary guardian often appointed when legal issues are pending) challenged the ruling, arguing the probate court cannot empower the guardian to consent to involuntary medication administration. On appeal, the court ruled:

- the guardianship was justified

- the standard of proof for establishment of a guardianship is preponderance of the evidence (Table 27)

- the guardian must seek from a court a “substituted judgment” to authorize forcible administration of antipsychotic medication.

The decision to establish the court as the final decision maker is based on the view that a patient’s relatives may be biased. Courts should take an objective approach that considers

- patient preference stated during periods of competency

- medication adverse effects

- consequences if treatment is refused

- prognosis with treatment

- religious beliefs

- impact on the patient’s family.

Continue to: This case set the stage for...

This case set the stage for later decisions that placed antipsychotic medications in the same category as electroconvulsive therapy and psychosurgery. This could mean a guardian would need specialized authorization to request antipsychotic treatment but could consent to an appendectomy without legal issue.

Fortunately, now most jurisdictions have remedied this cumbersome solution by requiring a higher standard of proof, clear and convincing evidence (Table 27), to establish guardianship but allowing the guardian more latitude to make decisions for their wards (such as those involving hospital admission or medications) without further court involvement.

Involuntary medical treatment

In order for a patient to consent for medical treatment, he/she must have the capacity to do so (Table 59). How do the courts handle the patient’s right to refuse medical treatment? This was addressed in the case of Georgetown College v Jones.19 Mrs. Jones, a 25-year-old Jehovah’s Witness and mother of a 7-month-old baby, suffered a ruptured ulcer and lost a life-threatening amount of blood. Due to her religious beliefs, Mrs. Jones refused a blood transfusion. The hospital quickly appealed to the court, who ruled the woman was help-seeking by going to the hospital, did not want to die, was in distress, and lacked capacity to make medical decisions. Acting in a parens patriae manner (when the government steps in to make decisions for its citizens who cannot), the court ordered the hospital to administer blood transfusions.

Proxy decision maker. When the situation is less emergent, a proxy decision maker can be appointed by the court. This was addressed in the case of Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz.20 Mr. Saikewicz, a 67-year-old man with intellectual disability, was diagnosed with cancer and given weeks to months to live without treatment. However, treatment was only 50% effective and could potentially cause severe adverse effects. A guardian ad litem was appointed and recommended nontreatment, which the court upheld. The court ruled that the right to accept or reject medical treatment applies to both incompetent and competent persons. With incompetent persons, a “substituted judgment” analysis is used over the “best interest of the patient” doctrine.20 This falls in line with the Guardianship of Richard Roe III ruling,18 in which the court’s substituted judgment standard is enacted in an effort to respect patient autonomy.

Right to die. When does a patient have the right to die and what is the standard of proof? The US Supreme Court case Cruzan v Director21 addressed this. Nancy Cruzan was involved in a car crash, which left her in a persistent vegetative state with no significant cognitive function. She remained this way for 6 years before her parents sought to terminate life support. The hospital refused. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled that a standard of clear and convincing evidence (Table 27) is required to withdraw treatment, and in a 5-to-4 decision, the US Supreme Court upheld Missouri’s decision. This set the national standard for withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. The moderate standard of proof is based on the court’s ruling that the decision to terminate life is a particularly important one.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

After having been civilly committed to your inpatient psychiatric facility, Ms. T’s paranoia and disorganized behavior persist. She continues to refuse medications.

There are 3 options: respect her decision, negotiate with her, or attempt to force medications through due process.11 In negotiating a compromise, it is best to understand the barriers to treatment. A patient may refuse medications due to poor insight into his/her illness, medication adverse effects, a preference for an alternative treatment, delusional concerns over contamination and/or poisoning, interpersonal conflicts with the treatment staff, a preference for symptoms (eg, mania) over wellness, medication ineffectiveness, length of treatment course, or stigma.22,23 However, a patient’s unwillingness to compromise creates the dilemma of autonomy vs treatment.

For Ms. T, the treatment team felt initiating involuntary medication was the best option for her quality of life and safety. Because she resides in Ohio, a Rogers-like model was applied. The probate court was petitioned and found her incompetent to make medical decisions. The court accepted the physician’s recommendation of treatment with antipsychotic medications. If this scenario took place in New Jersey, a Rennie model would apply, requiring due process through the second opinion of another physician. Lastly, if Ms. T lived in Utah, she would have been unable to refuse medications once civilly committed.

Pros and cons of each model

Over the years, various concerns about each of these models have been raised. Given the slow-moving wheels of justice, one concern was that perhaps patients would be left “rotting with their rights on,” or lingering in a psychotic state out of respect for their civil liberties.19 While court hearings do not always happen quickly, more often than not, a judge will agree with the psychiatrist seeking treatment because the judge likely has little experience with mental illness and will defer to the physician’s expertise. This means the Rogers model may be more likely to produce the desired outcome, just more slowly. With respect to the Rennie model, although it is often more expeditious, the second opinion of an independent psychiatrist may contradict that of the original physician because the consultant will rely on his/her own expertise. Finally, some were concerned that psychiatrists would view the Utah model as carte blanche to start whatever medications they wanted with no respect for patient preference. Based on our clinical experience, none of these concerns have come to fruition over time, and patients safely receive medications over objection in hospitals every day.

Consider why the patient refuses medication

Regardless of which involuntary medication model is employed, it is important to consider the underlying cause for medication refusal, because it may affect future compliance. If the refusal is the result of a religious belief, history of adverse effects, or other rational motive, then it may be reasonable to respect the patient’s autonomy.24 However, if the refusal is secondary to symptoms of mental illness, it is appropriate to move forward with an involuntary medication hearing and treat the underlying condition.

Continue to: In the case of Ms. T...

In the case of Ms. T, she appeared to be refusing medications because of her psychotic symptoms, which could be effectively treated with antipsychotic medications. Therefore, Ms. T’s current lack of capacity is hopefully a transient phenomenon that can be ameliorated by initiating medication. Typically, antipsychotic medications begin to reduce psychotic symptoms within the first week, with further improvement over time.25 The value of the inpatient psychiatric setting is that it allows for daily monitoring of a patient’s response to treatment. As capacity is regained, patient autonomy over medical decisions is reinstated.

Bottom Line

The legal processes required to administer medications over a patient’s objection are state-specific, and multiple models are used. In general, a patient’s right to refuse treatment can be overruled by obtaining adjudication through the courts (Rogers model) or the opinion of a second physician (Rennie model). In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, research the legal procedure specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

Related Resources

- Miller D. Is forced treatment in our outpatients’ best interests? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/80277/forced-treatment-our-outpatients-best-interests.

- Miller D, Hanson A. Committed: The battle over involuntary psychiatric care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

1. Laffey P. Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1285-1297.

2. Porter R. Madness: a brief history. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2002.

3. Stetka B, Watson J. Odd and outlandish psychiatric treatments throughout history. Medscape Psychiatry. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/odd-psychiatric-treatments. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2020.

4. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

5. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

6. Administrative Office of the US Courts. Comparing federal and state Courts. United States Courts. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure/comparing-federal-state-courts. Accessed February 26, 2020.

7. Drogin E, Williams C. Introduction to the Legal System. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:80-83.

8. Appelbaum P, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

9. Kambam P. Informed consent and competence. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:115-121.

10. Wall B, Anfang S. Legal regulation of psychiatric treatment. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:306-333.

11. Pinals D, Nesbit A, Hoge S. Treatment refusal in psychiatric practice. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:155-163.

12. Rogers v Commissioner, 390 489 (Mass 1983).

13. Steele v Hamilton County, 90 Ohio St3d 176 (Ohio 2000).

14. Rennie v Klein, 462 F Supp 1131 (D NJ 1978).

15. AE and RR v Mitchell, 724 F.2d 864 (10th Cir 1983).

16. Washington v Harper, 494 US 210 (1990).

17. Sell v US, 539 US 166 (2003).

18. Guardianship of Richard Roe III, 383 415, 435 (Mass 1981).

19. Georgetown College v Jones, 331 F2d 1010 (DC Cir 1964).

20. Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz, 370 NE 2d 417 (1977).

21. Cruzan v Director, 497 US 261 (1990).

22. Owiti J, Bowers L. A literature review: refusal of psychotropic medication in acute inpatient psychiatric care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(7):637-647.

23. Appelbaum P, Gutheil T. “Rotting with their rights on”: constitutional theory and clinical reality in drug refusal by psychiatric patients. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1979;7(3):306-315.

24. Adelugba OO, Mela M, Haq IU. Psychotropic medication refusal: reasons and patients’ perception at a secure forensic psychiatric treatment centre. J Forensic Sci Med. 2016;2(1):12-17.

25. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228.

1. Laffey P. Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1285-1297.

2. Porter R. Madness: a brief history. New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2002.

3. Stetka B, Watson J. Odd and outlandish psychiatric treatments throughout history. Medscape Psychiatry. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/odd-psychiatric-treatments. Published April 13, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2020.

4. Rouse v Cameron, 373, F2d 451 (DC Cir 1966).

5. Wyatt v Stickney, 325 F Supp 781 (MD Ala 1971).

6. Administrative Office of the US Courts. Comparing federal and state Courts. United States Courts. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure/comparing-federal-state-courts. Accessed February 26, 2020.

7. Drogin E, Williams C. Introduction to the Legal System. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:80-83.

8. Appelbaum P, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

9. Kambam P. Informed consent and competence. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:115-121.

10. Wall B, Anfang S. Legal regulation of psychiatric treatment. In: Gold L, Frierson R, eds. Textbook of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:306-333.

11. Pinals D, Nesbit A, Hoge S. Treatment refusal in psychiatric practice. In: Rosnar R, Scott C, eds. Principles and practice of forensic psychiatry, 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2017:155-163.

12. Rogers v Commissioner, 390 489 (Mass 1983).

13. Steele v Hamilton County, 90 Ohio St3d 176 (Ohio 2000).

14. Rennie v Klein, 462 F Supp 1131 (D NJ 1978).

15. AE and RR v Mitchell, 724 F.2d 864 (10th Cir 1983).

16. Washington v Harper, 494 US 210 (1990).

17. Sell v US, 539 US 166 (2003).

18. Guardianship of Richard Roe III, 383 415, 435 (Mass 1981).

19. Georgetown College v Jones, 331 F2d 1010 (DC Cir 1964).

20. Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz, 370 NE 2d 417 (1977).

21. Cruzan v Director, 497 US 261 (1990).

22. Owiti J, Bowers L. A literature review: refusal of psychotropic medication in acute inpatient psychiatric care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(7):637-647.

23. Appelbaum P, Gutheil T. “Rotting with their rights on”: constitutional theory and clinical reality in drug refusal by psychiatric patients. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1979;7(3):306-315.

24. Adelugba OO, Mela M, Haq IU. Psychotropic medication refusal: reasons and patients’ perception at a secure forensic psychiatric treatment centre. J Forensic Sci Med. 2016;2(1):12-17.

25. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228.