User login

Paraphilic disorders and sexual criminality

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

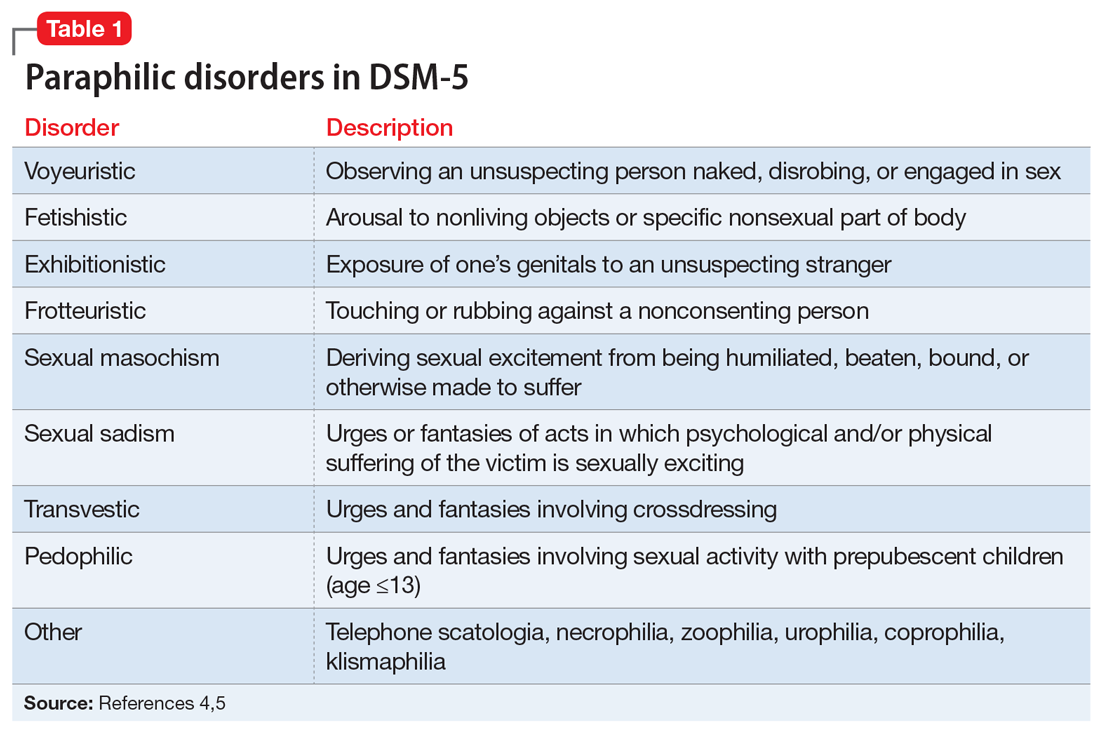

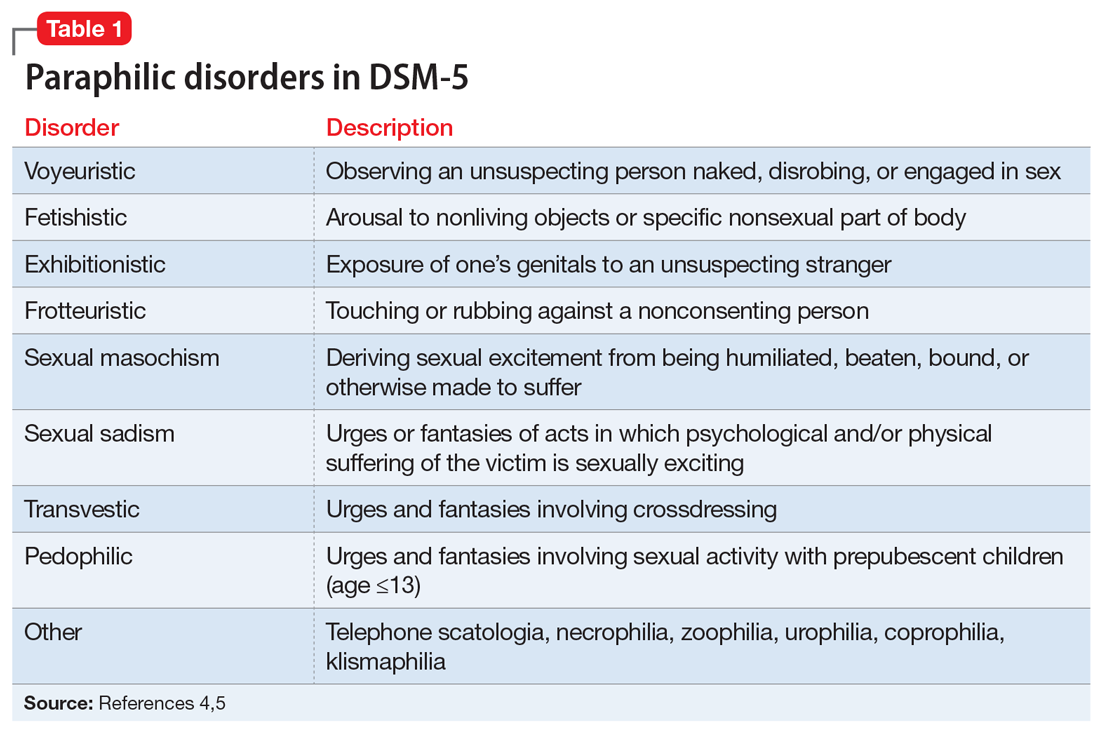

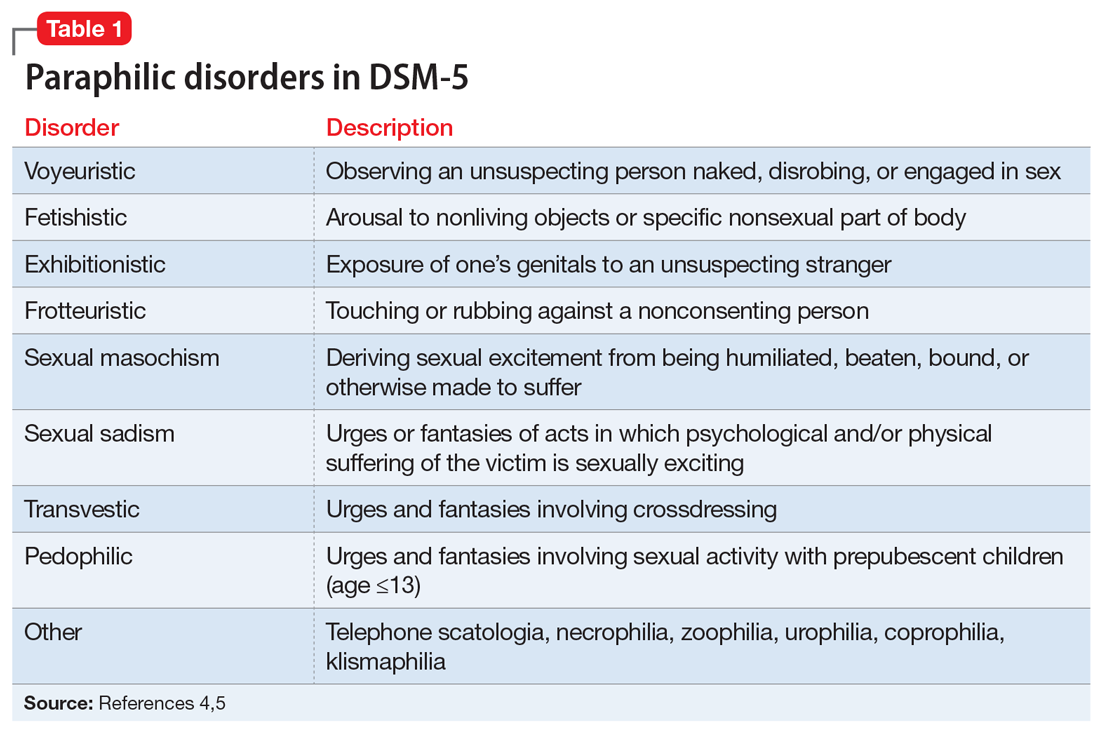

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

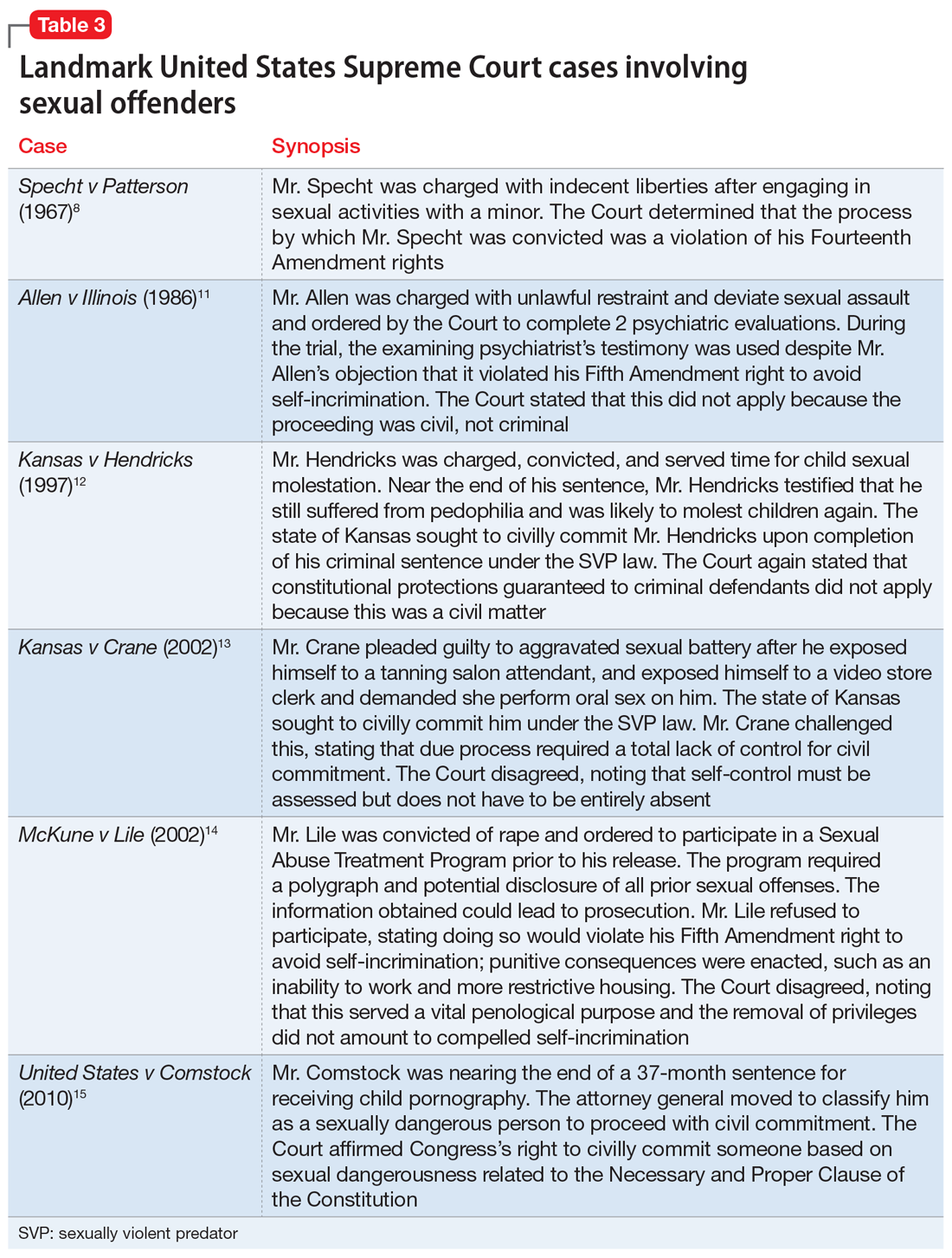

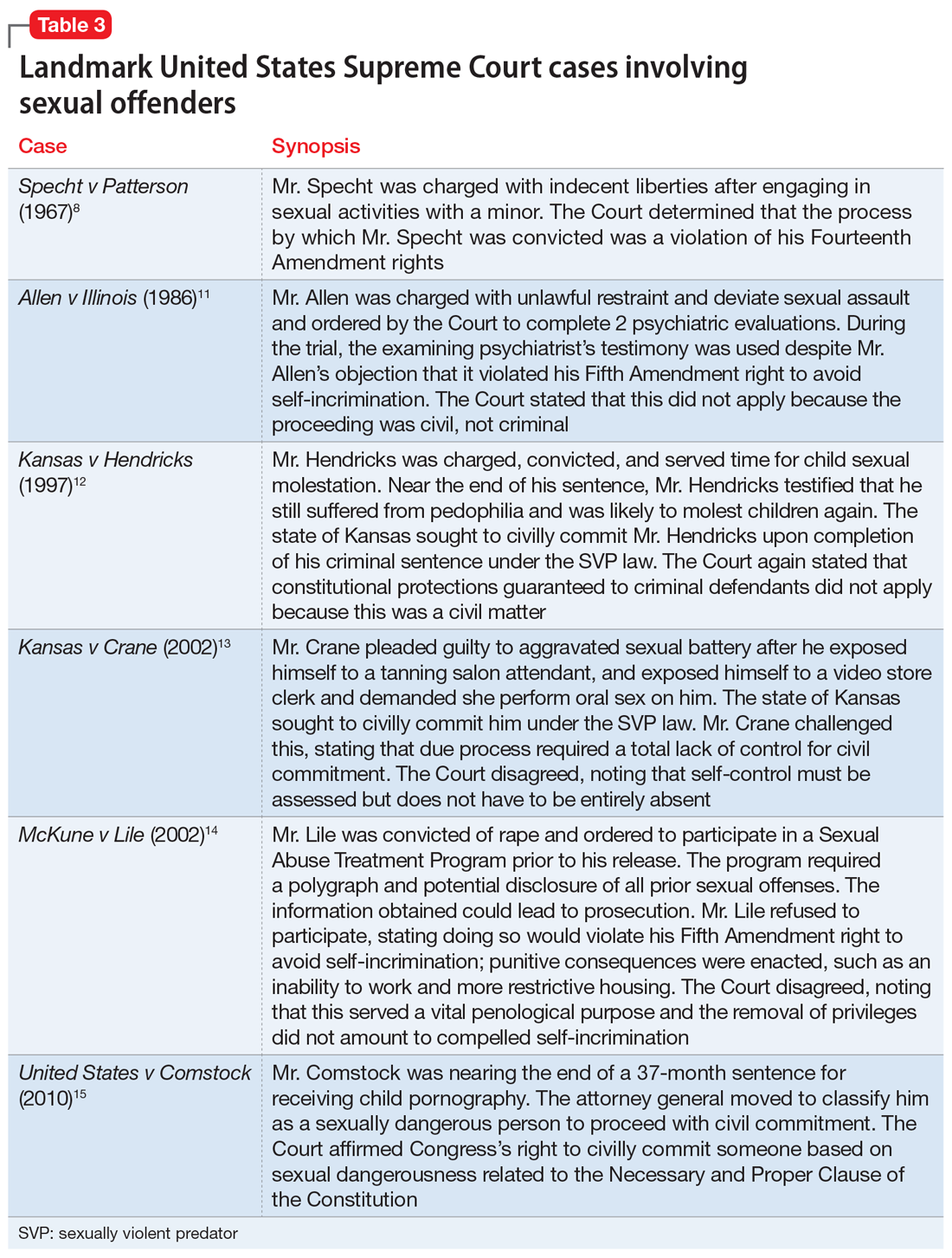

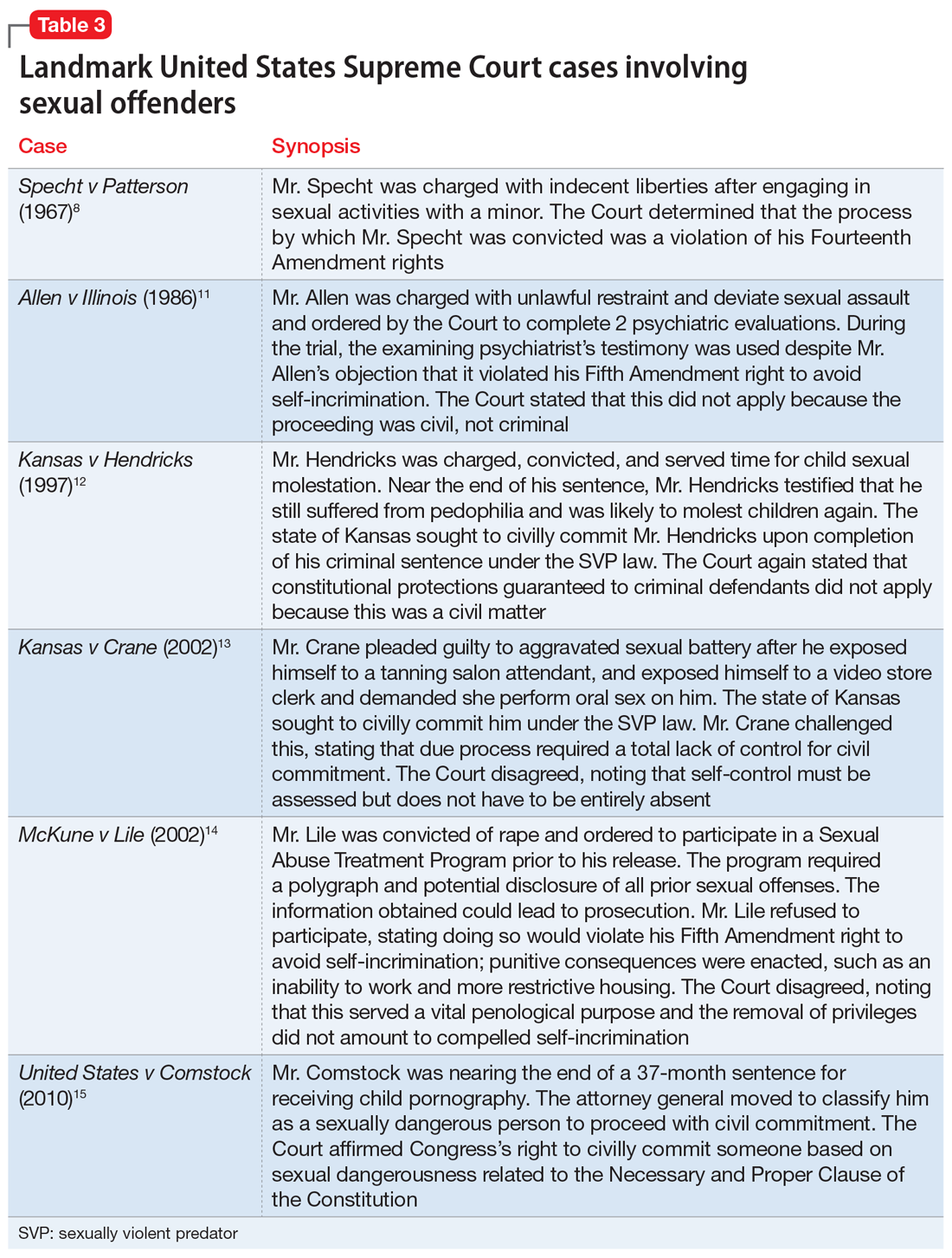

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

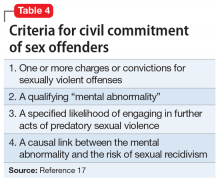

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

Mr. J, age 23, presents to an outpatient mental health clinic for treatment of anxiety. He has no psychiatric history, is dressed neatly, and recently finished graduate school with a degree in accounting. Mr. J is reserved during the initial psychiatric evaluation and provides only basic facts about his developmental history.

Mr. J comes from a middle-class household with no history of trauma or substance use. He does not report any symptoms consistent with anxiety, but discloses a history of sexual preoccupations. Mr. J says that during adolescence he developed a predilection for observing others engage in sexual activity. In his late teens, he began following couples to their homes in the hope of witnessing sexual intimacy. In the rare instance that his voyeuristic fantasy comes to fruition, he masturbates and achieves sexual gratification he is incapable of experiencing otherwise. Mr. J notes that he has not yet been caught, but he expresses concern and embarrassment related to his actions. He concludes by noting that he seeks help because the frequency of this behavior has steadily increased.

How would you treat Mr. J? Where does the line exist between a normophilic sexual interest, fantasy or urge, and a paraphilia? Does Mr. J qualify as a sexually violent predator?

From The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Fifty Shades of Grey, sensationalized portrayals of sexual deviancy have long been present in popular culture. The continued popularity of serial killers years after their crimes seems in part related to the extreme sexual torture their victims often endure. However, a sexual offense does not always qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1 In fact, many individuals with paraphilic disorders never engage in illegal activity. Additionally, experiencing sexually deviant thoughts alone does not qualify as a paraphilic disorder.1

A thorough psychiatric evaluation should include a discussion of the patient’s sexual history, including the potential of sexual dysfunction and abnormal desires or behaviors. Most individuals with sexual dysfunction do not have a paraphilic disorder.2 DSM-5 and ICD-11 classify sexual dysfunction and paraphilic disorders in different categories. However, previous editions grouped them together under sexual and gender identity disorders. Individuals with paraphilic disorders may not originally present to the outpatient setting for a paraphilic disorder, but instead may first seek treatment for a more common comorbid disorder, such as a mood disorder, personality disorder, or substance use disorder.3

Diagnostically speaking, if individuals do not experience distress or issues with functionality and lack legal charges (suggesting that they have not violated the rights of others), they are categorized as having an atypical sexual interest but do not necessarily meet the criteria for a disorder.4 This article provides an overview of paraphilic disorders as well as forensic considerations when examining individuals with sexually deviant behaviors.

Overview of paraphilic disorders

DSM-5 characterizes a paraphilic disorder as “recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving nonhuman objects or nonconsenting partners for at least 6 months. The individual must have acted on the thought and/or it caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” DSM-5 outlines 9 categories of paraphilic disorders, which are described in Table 1.4,5

Continue to: Paraphilic disorders are more common...

Paraphilic disorders are more common in men than in women; the 2 most prevalent are voyeuristic disorder and frotteuristic disorder.6 The incidence of paraphilias in the general outpatient setting varies by disorder. Approximately 45% of individuals with pedophilic disorder seek treatment, whereas only 1% of individuals with zoophilia seek treatment.6 The incidence of paraphilic acts also varies drastically; individuals with exhibitionistic disorder engaged in an average of 50 acts vs only 3 for individuals with sexual sadism.6 Not all individuals with paraphilic disorders commit crimes. Approximately 58% of sexual offenders meet the criteria for a paraphilic disorder, but antisocial personality disorder is a far more common diagnosis.7

Sexual psychopath statutes: Phase 1

In 1937, Michigan became the first state to enact sexual psychopath statutes, allowing for indeterminate sentencing and the civil commitment/treatment of sex offenders with repeated convictions. By the 1970s, more than 30 states had enacted similar statutes. It was not until 1967, in Specht v Patterson,8 that the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause was violated when Francis Eddie Specht faced life in prison following his conviction for indecent liberties under the Colorado Sex Offenders Act.

Specht was convicted in 1959 for indecent liberties after pleading guilty to enticing a child younger than age 16 into an office and engaging in sexual activities with them. At the time of Specht’s conviction, the crime of indecent liberties carried a punishment of 10 years. However, Specht was sentenced under the Sexual Offenders Act, which allowed for an indeterminate sentence of 1 day to life in prison. The Supreme Court noted that Specht was denied the right to be present with counsel, to confront the evidence against him, to cross-examine witnesses, and to offer his own evidence, which was a violation of his constitutionally guaranteed Fourteenth Amendment right to Procedural Due Process. The decision led most states to repeal early sexual psychopath statutes.8

Sexually violent predator laws: Phase 2

After early sexual psychopath statutes were repealed, many states pushed to update sex offender laws in response to the Earl Shriner case.9 In 1989, Shriner was released from prison after serving a 10-year sentence for sexually assaulting 2 teenage girls. At the time, he did not meet the criteria for civil commitment in the state of Washington. On the day he was released, Shriner cut off a young boy’s penis and left him to die. Washington subsequently became the first of many states to enact sexually violent predator (SVP) laws. Table 210 shows states and districts that have SVP civil commitment laws.

A series of United States Supreme Court cases solidified current sexual offender civil commitment laws (Table 38,11-15).

Continue to: Allen v Illinois

Allen v Illinois (1986).11 The Court ruled that forcing an individual to participate in a psychiatric evaluation prior to a sexually dangerous person’s commitment hearing did not violate the individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination because the purpose of the evaluation was to provide treatment, not punishment.

Kansas v Hendricks (1997).12 The Court upheld that the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act was constitutional and noted that the use of the broad term “mental abnormality” (in lieu of the more specific term “mental illness”) does not violate an individual’s Fourteenth Amendment right to substantive due process. Additionally, the Court opined that the constitutional ban on double jeopardy and ex post facto lawmaking does not apply because the procedures are civil, not criminal.

Kansas v Crane (2002).13 The Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act, stating that mental illness and dangerousness are essential elements to meet the criteria for civil commitment. The Court added that proof of partial (not total) “volitional impairment” is all that is required to meet the threshold of sexual dangerousness.

McKune v Lile (2002).14 The Court ruled that a policy requiring participation in polygraph testing, which would lead to the disclosure of sexual crimes (even those that have not been prosecuted), does not violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment rights because it serves a vital penological purpose.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 200616; United States v Comstock (2010).15 This act and subsequent case reinforced the federal government’s right to civilly commit sexually dangerous persons approaching the end of their prison sentences.

Continue to: What is requiried for civil commitment?

What is required for civil commitment?

SVP laws require 4 conditions to be met for the civil commitment of sexual offenders (Table 417). In criteria 1, “charges” is a key word, because this allows individuals found Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity or Incompetent to Stand Trial to be civilly committed. Criteria 2 defines “mental abnormality” as a “congenital or acquired condition affecting the emotional or volitional capacity which predisposes the person to commit criminal sexual acts in a degree constituting such person a menace to the health and safety of others.”18 This is a broad definition, and allows individuals with personality disorders to be civilly committed (although most sexual offenders are committed for having a paraphilic disorder). To determine risk, various actuarial instruments are used to assess for sexually violent recidivism, including (but not limited to) the Static-99R, Sexual Violence Risk-20, and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.19

Although the percentages vary, sex offenders rarely are civilly committed following their criminal sentence. In California, approximately 1.5% of sex offenders are civilly committed.17 The standard of proof for civil commitment varies by state between “clear and convincing evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt.” As sex offenders approach the end of their sentence, sexually violent offenders are identified to the general population and referred for a psychiatric evaluation. If the individual meets the 4 criteria for commitment (Table 417), their case is sent to the prosecuting attorney’s office. If accepted, the court holds a probable cause hearing, followed by a full trial.

Pornography and sex offenders

Pornography has long been considered a risk factor for sexual offending, and the role of pornography in influencing sexual behavior has drawn recent interest in research towards predicting future offenses. However, a 2019 systematic review by Mellor et al20 on the relationship between pornography and sexual offending suggested that early exposure to pornography is not a risk factor for sexual offending, nor is the risk of offending increased shortly after pornography exposure. Additionally, pornography use did not predict recidivism in low-risk sexual offenders, but did in high-risk offenders.

The use of child pornography presents a set of new risk factors. Prohibited by federal and state law, child pornography is defined under Section 2256 of Title 18, United States Code, as any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor (someone <age 18). Visual depictions include photographs, videos, digital or computer-generated images indistinguishable from an actual minor, and images created to depict a minor. The law does not require an image of a child engaging in sexual activity for the image to be characterized as child pornography. Offenders are also commonly charged with the distribution of child pornography. A conviction of child pornography possession carries a 15- to 30-year sentence, and distribution carries a 5- to 20-year sentence.21 The individual must also file for the sex offender registry, which may restrict their employment and place of residency.

It is unclear what percentage of individuals charged with child pornography have a history of prior sexual offenses. Numerous studies suggest there is a low risk of online offenders without prior offenses becoming contact offenders. Characteristics of online-only offenders include being White, a single male, age 20 to 30, well-educated, and employed, and having antisocial traits and a history of sexual deviancy.22 Contact offenders tend to be married with easy access to children, unemployed, uneducated, and to have a history of mental illness or criminal offenses.22

Continue to: Recidivism and treatment

Recidivism and treatment

The recidivism rate among sexual offenders averages 13.7% at 3- to 6-year follow-up,although rates vary by type of sexual offense.23 Individuals who committed rape have the highest rate of recidivism, while those who engaged in incest have the lowest. Three key points about sexual offender recidivism are:

- it declines over time and with increased age.

- sexual offenders are more like to commit a nonsexual offense than a sexual offense.

- sexual offenders who have undergone treatment are 26.3% less likely to reoffend.23

Although there is no standard of treatment, current interventions include external control, reduction of sexual drive, treatment of comorbid conditions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and dynamic psychotherapy. External control relies on an outside entity that affects the individual’s behavior. For sexually deviant behaviors, simply making the act illegal or involving the law may inhibit many individuals from acting on a thought. Additional external control may include pharmacotherapy, which ranges from nonhormonal options such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to hormonal options. Therapy tends to focus on social skills training, sex education, cognitive restructuring, and identifying triggers, as well as victim empathy. The best indicators for successful treatment include an absence of comorbidities, increased age, and adult interpersonal relationships.24

Treatment choice may be predicated on the severity of the paraphilia. Psychotherapy alone is recommended for individuals able to maintain functioning if it does not affect their conventional sexual activity. Common treatment for low-risk individuals is psychotherapy and an SSRI. As risk increases, so does treatment with pharmacologic agents. Beyond SSRIs, moderate offenders may be treated with an SSRI and a low-dose antiandrogen. This is escalated in high-risk violent offenders to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and synthetic steroidal analogs.25

An evolving class of disorders

With the evolution and accessibility of pornography, uncommon sexual practices have become more common, gaining notoriety and increased social acceptance. As a result, mental health professionals may be tasked with evaluating patients for possible paraphilic disorders. A common misconception is that individuals with sexually deviant thoughts, sexual offenders, and patients with paraphilic disorders are all the same. However, more commonly, sexual offenders do not have a paraphilic disorder. In the case of SVPs, outside of imprisonment, civil commitment remains a consideration for possible treatment. To meet the threshold of civil commitment, a sexual offender must have a “mental abnormality,” which is most commonly a paraphilic disorder. The treatment of paraphilic disorders remains a difficult task and includes a mixture of psychotherapy and medication options.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J begins weekly CBT to gain control of his voyeuristic fantasies without impacting his conventional sexual activity and desire. He responds well to treatment, and after 18 months, begins a typical sexual relationship with a woman. Although his voyeuristic thoughts remain, the urge to act on the thoughts decreases as Mr. J develops coping mechanisms. He does not require pharmacologic treatment.

Bottom Line

Individuals with paraphilic disorders are too often portrayed as sexual deviants or criminals. Psychiatrists must review each case with careful consideration of individual risk factors, such as the patient’s sexual history, to evaluate potential treatment options while determining if they pose a threat to the public.

Related Resources

- Sorrentino R, Abramowitz J. Minor-attracted persons: a neglected population. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(7):21-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0149

- Berlin FS. Paraphilic disorders: a better understanding. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):22-26,28.

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).

1. Federoff JP. The paraphilias. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Geddes JR, eds. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012:832-842.

2. Grubin D. Medical models and interventions in sexual deviance. In: Laws R, O’Donohue WT, eds. Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment and Treatment. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2008:594-610.

3. Guidry LL, Saleh FM. Clinical considerations of paraphilic sex offenders with comorbid psychiatric conditions. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2004;11(1-2):21-34.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Balon R. Paraphilic disorders. In: Roberts LW, Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 7th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:749-770.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Paraphilic disorders. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2015:593-599.

7. First MB, Halon RL. Use of DSM paraphilia diagnosis in sexually violent predator commitment cases. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(4):443-454.

8. Specht v Patterson, 386 US 605 (1967).

9. Ra EP. The civil confinement of sexual predators: a delicate balance. J Civ Rts Econ Dev. 2007;22(1):335-372.

10. Felthous AR, Ko J. Sexually violent predator law in the United States. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2018;28(4):159-173.

11. Allen v Illinois, 478 US 364 (1986).

12. Kansas v Hendricks, 521 US 346 (1997).

13. Kansas v Crane, 534 US 407 (2002).

14. McKune v Lile, 536 US 24 (2002).

15. United States v Comstock, 560 US 126 (2010).

16. Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006, HR 4472, 109th Cong (2006). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4472

17. Tucker DE, Brakel SJ. Sexually violent predator laws. In: Rosner R, Scott C, eds. Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2017:823-831.

18. Wash. Rev. Code. Ann. §71.09.020(8)

19. Bradford J, de Amorim Levin GV, Booth BD, et al. Forensic assessment of sex offenders. In: Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:382-397.

20. Mellor E, Duff S. The use of pornography and the relationship between pornography exposure and sexual offending in males: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Beh. 2019;46:116-126.

21. Failure To Register, 18 USC § 2250 (2012). Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title18/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap109B-sec2250

22. Hirschtritt ME, Tucker D, Binder RL. Risk assessment of online child sexual exploitation offenders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47(2):155-164.

23. Blasko BL. Overview of sexual offender typologies, recidivism, and treatment. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Sexual Violence: Evidence Based Policy and Prevention. Springer; 2016:11-29.

24. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490.

25. Holoyda B. Paraphilias: from diagnosis to treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2019;36(12).

Does your patient have the right to refuse medications?

Ms. T, age 48, is brought to the psychiatric emergency department after the police find her walking along the highway at 3:00

Once involuntarily committed, does Ms. T have the right to refuse treatment?

Every psychiatrist has faced the predicament of a patient who refuses treatment. This creates an ethical dilemma between respecting the patient’s autonomy vs forcing treatment to ameliorate symptoms and reduce suffering. This article addresses case law related to the models for administering psychiatric medications over objection. We also discuss case law regarding court-appointed guardianship, and treating medical issues without consent. While this article provides valuable information on these scenarios, it is crucial to remember that the legal processes required to administer medications over patient objection are state-specific. In order to ensure the best practice and patient care, you must research the legal procedures specific to your jurisdiction, consult your clinic/hospital attorney, and/or contact your state’s mental health board for further clarification.

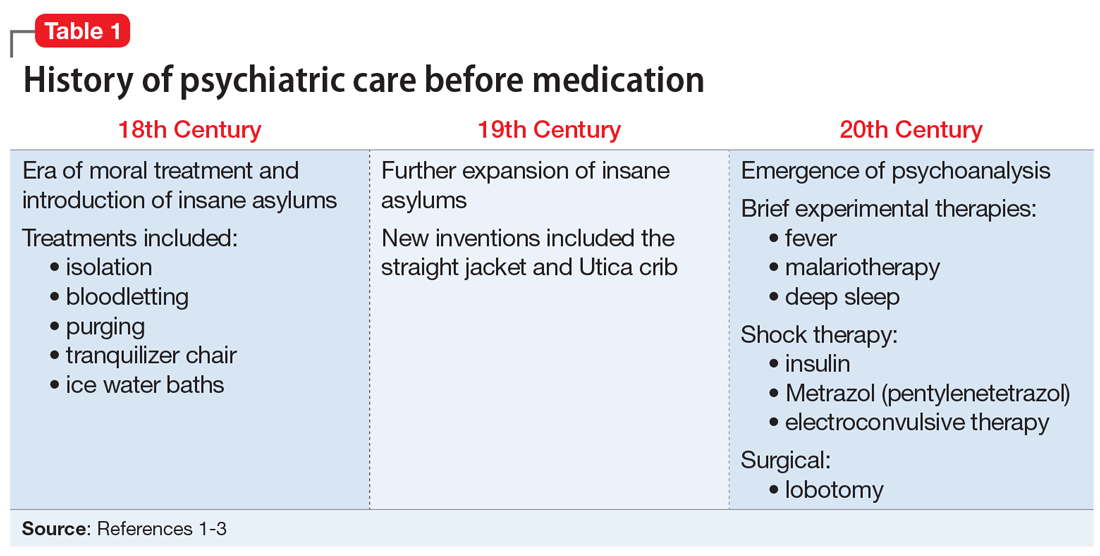

History of involuntary treatment

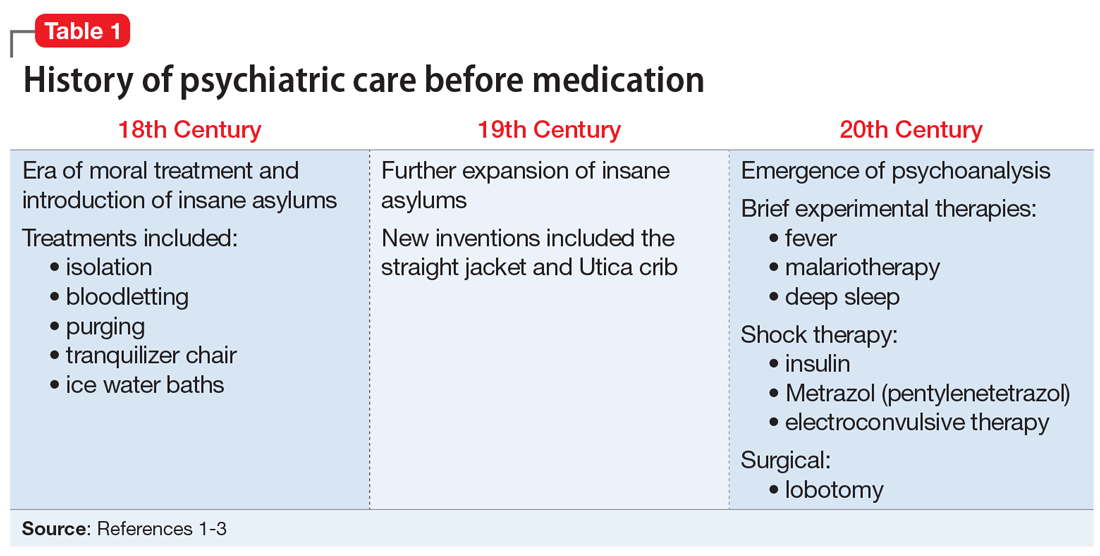

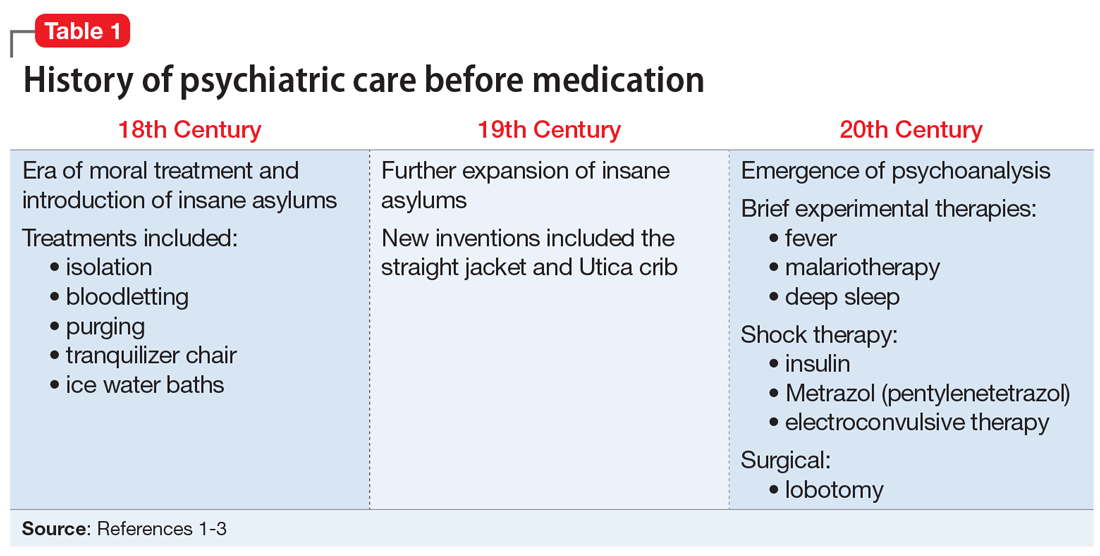

Prior to the 1960s, Ms. T would likely have been unable to refuse treatment. All patients were considered involuntary, and the course of treatment was decided solely by the psychiatric institution. Well into the 20th century, patients with psychiatric illness remained feared and stigmatized, which led to potent and potentially harsh methods of treatment. Some patients experienced extreme isolation, whipping, bloodletting, experimental use of chemicals, and starvation (Table 11-3).

With the advent of psychotropic medications and a focus on civil liberties, the psychiatric mindset began to change from hospital-based treatment to a community-based approach. The value of psychotherapy was recognized, and by the 1960s, the establishment of community mental health centers was gaining momentum.

In the context of these changes, the civil rights movement pressed for stronger legislation regarding autonomy and the quality of treatment available to patients with psychiatric illness. In the 1960s and 1970s, Rouse v Cameron4 and Wyatt v Stickney5 dealt with a patient’s right to receive treatment while involuntarily committed. However, it was not until the 1980s that the courts addressed the issue of a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

The judicial system: A primer

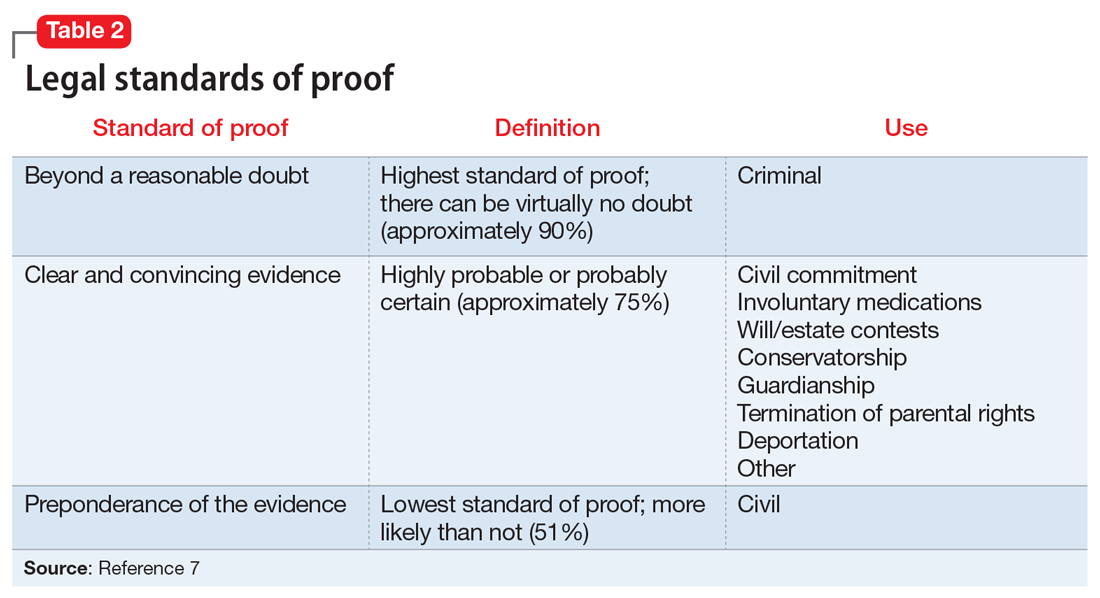

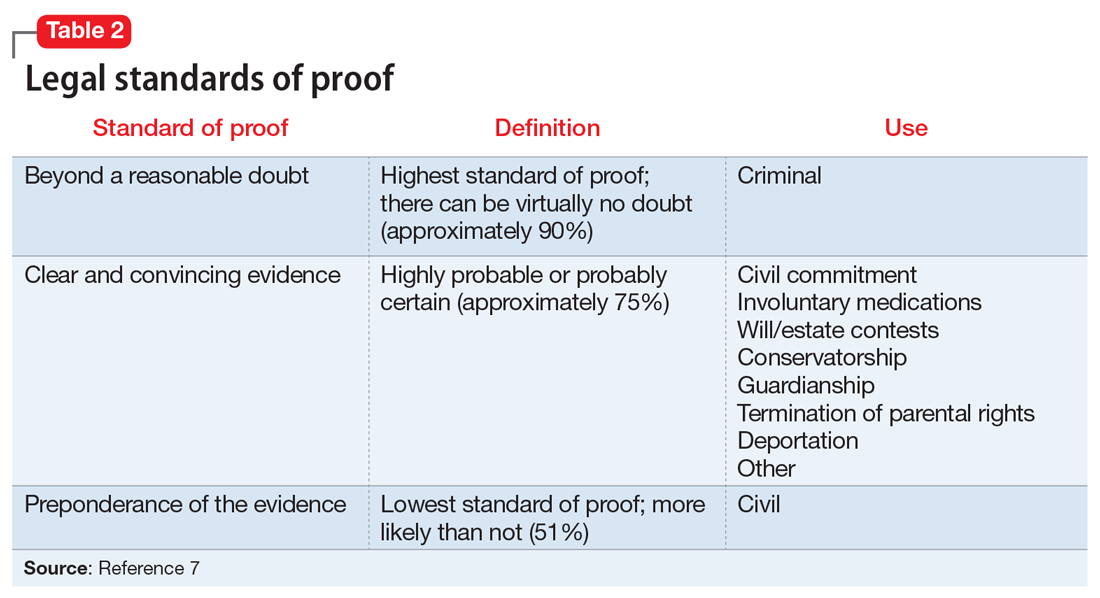

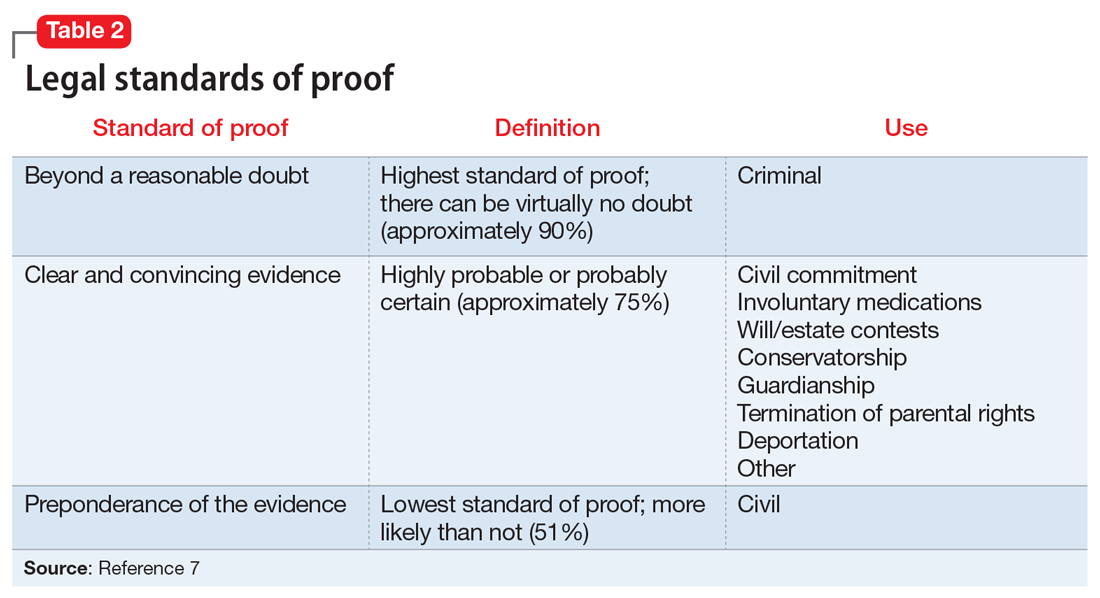

When reviewing case law and its applicability to your patients, it is important to understand the various court systems. The judicial system is divided into state and federal courts, which are subdivided into trial, appellate, and supreme courts. When decisions at either the state or federal level require an ultimate decision maker, the US Supreme Court can choose to hear the case, or grant certiorari, and make a ruling, which is then binding law.6 Decisions made by any court are based on various degrees of stringency, called standards of proof (Table 27).

Continue to: For Ms. T's case...

For Ms. T’s case, civil commitment and involuntary medication hearings are held in probate court, which is a civil (not criminal) court. In addition to overseeing civil commitment and involuntary medications, probate courts adjudicate will and estate contests, conservatorship, and guardianship. Conservatorship hearings deal with financial issues, and guardianship cases encompass personal and health-related needs. Regardless of the court, an individual is guaranteed due process under the 5th Amendment (federal) and 14th Amendment (state).

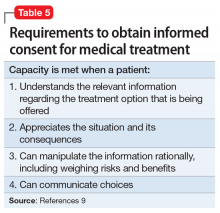

Individuals are presumed competent to make their own decisions, but a court may call this into question. Competencies are specific to a variety of areas, such as criminal proceedings, medical decision making, writing a will (testimonial capacity), etc. Because each field applies its own standard of competence, an individual may be competent in one area but incompetent in another. Competence in medical decision making varies by state but generally consists of being able to communicate a choice, understand relevant information, appreciate one’s illness and its likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information.8

Box

Administering medications despite a patient’s objection differs from situations in which medications are provided during a psychiatric emergency. In an emergency, courts do not have time to weigh in. Instead, emergency medications (most often given as IM injections) are administered based on the physician’s clinical judgment. The criteria for psychiatric emergencies are delineated at the state level, but typically are defined as when a person with a mental illness creates an imminent risk of harm to self or others. Alternative approaches to resolving the emergency may include verbal de-escalation, quiet time in a room devoid of stimuli, locked seclusion, or physical restraints. These measures are often exhausted before emergency medications are administered.

Source: Reference 9

It is important to note that the legal process required before administering involuntary medications is distinct from situations in which medication needs to be provided during a psychiatric emergency. The Box9 outlines the difference between these 2 scenarios.

4 Legal models

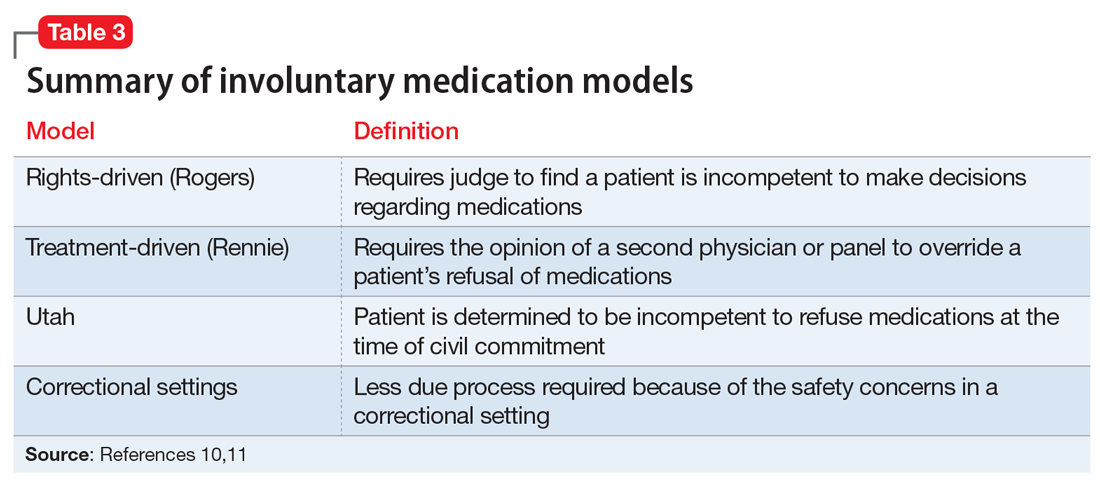

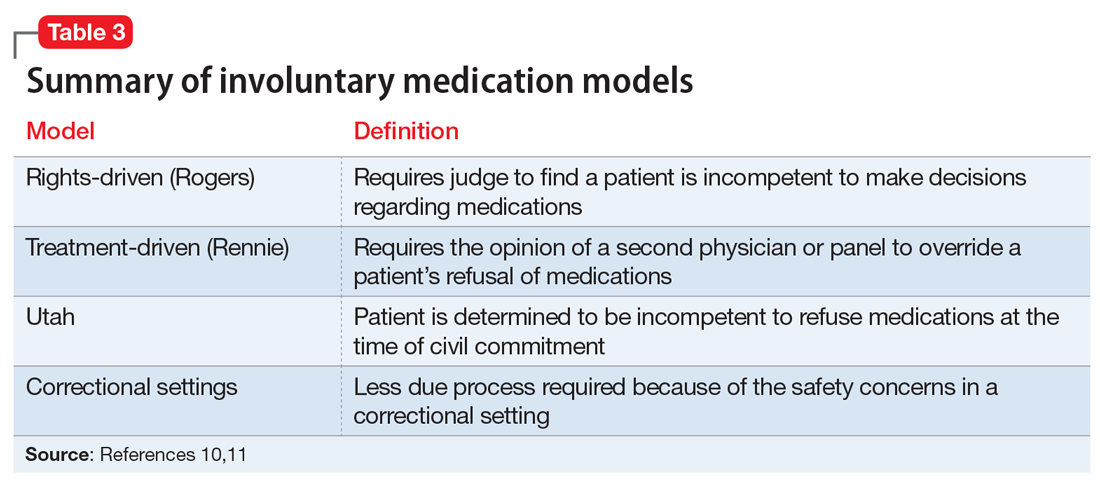

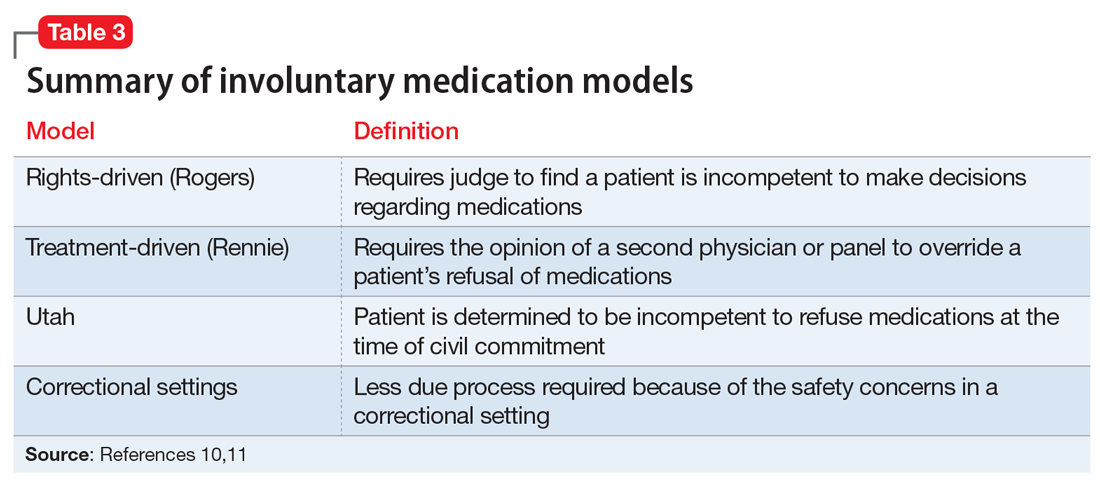

There are several legal models used to determine when a patient can be administered psychiatric medications over objection. Table 310,11 summarizes these models.

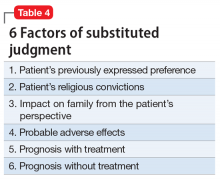

Rights-driven (Rogers) model. If Ms. T was involuntarily hospitalized in Massachusetts or another state that adopted the rights-driven model, she would retain the right to refuse treatment. These states require an external judicial review, and court approval is necessary before imposing any therapy. This model was established in Rogers v Commissioner,12 where 7 patients at the Boston State Hospital filed a lawsuit regarding their right to refuse medications. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that, despite being involuntarily committed, a patient is considered competent to refuse treatment until found specifically incompetent to do so by the court. If a patient is found incompetent, the judge, using a full adversarial hearing, decides what the incompetent patient would have wanted if he/she were competent. The judge reaches a conclusion based on the substituted judgment model (Table 410). In Rogers v Commissioner,12 the court ruled that the right to decision making is not lost after becoming a patient at a mental health facility. The right is lost only if the patient is found incompetent by the judge. Thus, every individual has the right to “manage his own person” and “take care of himself.”

Continue to: An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model

An update to the rights-driven (Rogers) model. Other states, such as Ohio, have adopted the Rogers model and addressed issues that arose subsequent to the aforementioned case. In Steele v Hamilton County,13 Jeffrey Steele was admitted and later civilly committed to the hospital. After 2 months, an involuntary medication hearing was completed in which 3 psychiatrists concluded that, although Mr. Steele was not a danger to himself or others while in the hospital, he would ultimately benefit from medications.

The probate court acknowledged that Mr. Steele lacked capacity and required hospitalization. However, because he was not imminently dangerous, medication should not be used involuntarily. After a series of appeals, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that a court may authorize the administration of an antipsychotic medication against a patient’s wishes without a finding of dangerousness when clear and convincing evidence exists that:

- the patient lacks the capacity to give or withhold informed consent regarding treatment

- the proposed medication is in the patient’s best interest

- no less intrusive treatment will be as effective in treating the mental illness.

This ruling set a precedent that dangerousness is not a requirement for involuntary medications.

Treatment-driven (Rennie) model. As in the rights-driven model, in the treatment-driven model, Ms. T would retain the constitutional right to refuse treatment. However, the models differ in the amount of procedural due process required. The treatment-driven model derives from Rennie v Klein,14 in which John Rennie, a patient at Ancora State Psychiatric Hospital in New Jersey, filed a suit regarding the right of involuntarily committed patients to refuse antipsychotic medications. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that, if professional judgment deems a patient to be a danger to himself or others, then antipsychotics may be administered over individual objection. This professional judgment is typically based on the opinion of the treating physician, along with a second physician or panel.

Utah model. This model is based on A.E. and R.R. v Mitchell,15 in which the Utah District Court ruled that a civilly committed patient has no right to refuse treatment. This Utah model was created after state legislature determined that, in order to civilly commit a patient, hospitalization must be the least restrictive alternative and the patient is incompetent to consent to treatment. Unlike the 2 previous models, competency to refuse medications is not separated from a previous finding of civil commitment, but rather, they occur simultaneously.

Continue to: Rights in unique situations

Rights in unique situations

Correctional settings. If Ms. T was an inmate, would her right to refuse psychiatric medication change? This was addressed in the case of Washington v Harper.16 Walter Harper, serving time for a robbery conviction, filed a claim that his civil rights were being violated when he received involuntary medications based on the decision of a 3-person panel consisting of a psychiatrist, psychologist, and prison official. The US Supreme Court ruled that this process provided sufficient due process to mandate providing psychotropic medications against a patient’s will. This reduction in required procedures is related to the unique nature of the correctional environment and an increased need to maintain safety. This need was felt to outweigh an individual’s right to refuse medication.

Incompetent to stand trial. In Sell v U.S.,17 Charles Sell, a dentist, was charged with fraud and attempted murder. He underwent a competency evaluation and was found incompetent to stand trial because of delusional thinking. Mr. Sell was hospitalized for restorability but refused medications. The hospital held an administrative hearing to proceed with involuntary antipsychotic medications; however, Mr. Sell filed an order with the court to prevent this. Eventually, the US Supreme Court ruled that non-dangerous, incompetent defendants may be involuntarily medicated even if they do not pose a risk to self or others on the basis that it furthers the state’s interest in bringing to trial those charged with serious crimes. However, the following conditions must be met before involuntary medication can be administered:

- an important government issue must be at stake (determined case-by-case)

- a substantial probability must exist that the medication will enable the defendant to become competent without significant adverse effects

- the medication must be medically appropriate and necessary to restore competency, with no less restrictive alternative available.

This case suggests that, before one attempts to forcibly medicate a defendant for the purpose of competency restoration, one should exhaust the same judicial remedies one uses for civil patients first.

Court-appointed guardianship

In the case of Ms. T, what if her father requested to become her guardian? This question was explored in the matter of Guardianship of Richard Roe III.18 Mr. Roe was admitted to the Northampton State Hospital in Massachusetts, where he refused antipsychotic medications. Prior to his release, his father asked to be his guardian. The probate court obliged the request. However, Mr. Roe’s lawyer and guardian ad litem (a neutral temporary guardian often appointed when legal issues are pending) challenged the ruling, arguing the probate court cannot empower the guardian to consent to involuntary medication administration. On appeal, the court ruled:

- the guardianship was justified

- the standard of proof for establishment of a guardianship is preponderance of the evidence (Table 27)

- the guardian must seek from a court a “substituted judgment” to authorize forcible administration of antipsychotic medication.

The decision to establish the court as the final decision maker is based on the view that a patient’s relatives may be biased. Courts should take an objective approach that considers

- patient preference stated during periods of competency

- medication adverse effects

- consequences if treatment is refused

- prognosis with treatment

- religious beliefs

- impact on the patient’s family.

Continue to: This case set the stage for...

This case set the stage for later decisions that placed antipsychotic medications in the same category as electroconvulsive therapy and psychosurgery. This could mean a guardian would need specialized authorization to request antipsychotic treatment but could consent to an appendectomy without legal issue.

Fortunately, now most jurisdictions have remedied this cumbersome solution by requiring a higher standard of proof, clear and convincing evidence (Table 27), to establish guardianship but allowing the guardian more latitude to make decisions for their wards (such as those involving hospital admission or medications) without further court involvement.

Involuntary medical treatment

In order for a patient to consent for medical treatment, he/she must have the capacity to do so (Table 59). How do the courts handle the patient’s right to refuse medical treatment? This was addressed in the case of Georgetown College v Jones.19 Mrs. Jones, a 25-year-old Jehovah’s Witness and mother of a 7-month-old baby, suffered a ruptured ulcer and lost a life-threatening amount of blood. Due to her religious beliefs, Mrs. Jones refused a blood transfusion. The hospital quickly appealed to the court, who ruled the woman was help-seeking by going to the hospital, did not want to die, was in distress, and lacked capacity to make medical decisions. Acting in a parens patriae manner (when the government steps in to make decisions for its citizens who cannot), the court ordered the hospital to administer blood transfusions.

Proxy decision maker. When the situation is less emergent, a proxy decision maker can be appointed by the court. This was addressed in the case of Superintendent of Belchertown v Saikewicz.20 Mr. Saikewicz, a 67-year-old man with intellectual disability, was diagnosed with cancer and given weeks to months to live without treatment. However, treatment was only 50% effective and could potentially cause severe adverse effects. A guardian ad litem was appointed and recommended nontreatment, which the court upheld. The court ruled that the right to accept or reject medical treatment applies to both incompetent and competent persons. With incompetent persons, a “substituted judgment” analysis is used over the “best interest of the patient” doctrine.20 This falls in line with the Guardianship of Richard Roe III ruling,18 in which the court’s substituted judgment standard is enacted in an effort to respect patient autonomy.

Right to die. When does a patient have the right to die and what is the standard of proof? The US Supreme Court case Cruzan v Director21 addressed this. Nancy Cruzan was involved in a car crash, which left her in a persistent vegetative state with no significant cognitive function. She remained this way for 6 years before her parents sought to terminate life support. The hospital refused. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled that a standard of clear and convincing evidence (Table 27) is required to withdraw treatment, and in a 5-to-4 decision, the US Supreme Court upheld Missouri’s decision. This set the national standard for withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. The moderate standard of proof is based on the court’s ruling that the decision to terminate life is a particularly important one.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

After having been civilly committed to your inpatient psychiatric facility, Ms. T’s paranoia and disorganized behavior persist. She continues to refuse medications.

There are 3 options: respect her decision, negotiate with her, or attempt to force medications through due process.11 In negotiating a compromise, it is best to understand the barriers to treatment. A patient may refuse medications due to poor insight into his/her illness, medication adverse effects, a preference for an alternative treatment, delusional concerns over contamination and/or poisoning, interpersonal conflicts with the treatment staff, a preference for symptoms (eg, mania) over wellness, medication ineffectiveness, length of treatment course, or stigma.22,23 However, a patient’s unwillingness to compromise creates the dilemma of autonomy vs treatment.

For Ms. T, the treatment team felt initiating involuntary medication was the best option for her quality of life and safety. Because she resides in Ohio, a Rogers-like model was applied. The probate court was petitioned and found her incompetent to make medical decisions. The court accepted the physician’s recommendation of treatment with antipsychotic medications. If this scenario took place in New Jersey, a Rennie model would apply, requiring due process through the second opinion of another physician. Lastly, if Ms. T lived in Utah, she would have been unable to refuse medications once civilly committed.

Pros and cons of each model

Over the years, various concerns about each of these models have been raised. Given the slow-moving wheels of justice, one concern was that perhaps patients would be left “rotting with their rights on,” or lingering in a psychotic state out of respect for their civil liberties.19 While court hearings do not always happen quickly, more often than not, a judge will agree with the psychiatrist seeking treatment because the judge likely has little experience with mental illness and will defer to the physician’s expertise. This means the Rogers model may be more likely to produce the desired outcome, just more slowly. With respect to the Rennie model, although it is often more expeditious, the second opinion of an independent psychiatrist may contradict that of the original physician because the consultant will rely on his/her own expertise. Finally, some were concerned that psychiatrists would view the Utah model as carte blanche to start whatever medications they wanted with no respect for patient preference. Based on our clinical experience, none of these concerns have come to fruition over time, and patients safely receive medications over objection in hospitals every day.

Consider why the patient refuses medication

Regardless of which involuntary medication model is employed, it is important to consider the underlying cause for medication refusal, because it may affect future compliance. If the refusal is the result of a religious belief, history of adverse effects, or other rational motive, then it may be reasonable to respect the patient’s autonomy.24 However, if the refusal is secondary to symptoms of mental illness, it is appropriate to move forward with an involuntary medication hearing and treat the underlying condition.

Continue to: In the case of Ms. T...

In the case of Ms. T, she appeared to be refusing medications because of her psychotic symptoms, which could be effectively treated with antipsychotic medications. Therefore, Ms. T’s current lack of capacity is hopefully a transient phenomenon that can be ameliorated by initiating medication. Typically, antipsychotic medications begin to reduce psychotic symptoms within the first week, with further improvement over time.25 The value of the inpatient psychiatric setting is that it allows for daily monitoring of a patient’s response to treatment. As capacity is regained, patient autonomy over medical decisions is reinstated.

Bottom Line