User login

Prescribe tamsulosin (typically 0.4 mg daily) or nifedipine (typically 30 mg daily) for patients with lower ureteral calculi, to speed stone passage and to avoid surgical intervention

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50:552-563.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up 2 days after he was seen in the ED and diagnosed with a distal ureteral calculus, his first. His pain is reasonably well controlled, but he has not yet passed the stone. Is there anything you can do to help him pass the stone?

Yes. Patients who are candidates for observation should be offered a trial of “medical expulsive therapy” using an α-antagonist or a calcium channel blocker. Until now, medical therapy for kidney stones consisted of pain relief only.

The ordeal of a first stone is all too common—the lifetime prevalence of kidney stones is 5.2%—and the probability of recurrence is about 50%.2,3

NHANES data show increasing prevalence between the periods 1976-1980 and 1988-1996.3 One fifth to one third of kidney stones require surgical intervention.4 In a cohort of 245 patients presenting to an ED in Canada, 50 (20%) required further procedures, including lithotripsy. Stones ≥ 6 mm in size were much less likely to pass (OR=10.7, 95% CI 4.6-24.8).5 The burden on the healthcare system is significant; there are approximately 2 million out-patient visits annually for this problem, and diagnosis and treatment costs about $2 billion annually.6

Watch and wait

The standard approach is a period of watchful waiting and pain control, with urgent urological referral for patients with evidence of upper urinary tract infection, high grade obstruction, inadequate pain or nausea control, or insufficient renal reserve.2,4 Most patients treated with watchful waiting pass their stone within 4 weeks. Any stones that don’t pass within 8 weeks are unlikely to pass spontaneously.2,7

Medical therapy has been proposed for decades

Medications that relax ureteral smooth muscle to help pass ureteral stones have been proposed for decades.8 Prior to 2000, however, only 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) of medical therapy for ureteral stones had been published.9 A subsequent meta-analysis found 9 studies and showed that medical therapy did increase the chances that a stone would pass.10 The Singh meta-analysis found 13 subsequently published studies and nearly tripled the number of patients evaluated.

STUDY SUMMARY: A well-done meta-analysis

This meta-analysis is based on 16 studies of α-antagonists (most used tamsulosin) and 9 studies of nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker.1 The studies were identified by a comprehensive search strategy that included Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register from January 1980 to January 2007. The authors included all randomized trials or controlled clinical trials of medical therapy for adults with acute ureteral colic.

The authors assessed the studies for quality using the Jadad scale, a validated scale of study quality. Higher scores represent better quality, including better documentation of randomization, blinding, and follow-up. The authors specified their planned sensitivity analyses, and used the random effects model to synthesize the results, which tends to provide a more conservative estimate of the effect.

In other words, this was a very well done meta-analysis.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria: 13 of α-antagonists, 6 of nifedipine, and 3 of both. In 13 of the 16 studies of α-antagonists, tamsulosin (Flomax) was the study drug. The results from the terazosin (Hytrin) and doxazosin (Cardura) studies were included with the tamsulosin studies. The Jadad quality scores of the 22 studies were fairly low, with a median of 2 (range of 0 to 3) on the 5-point scale. The most common deduction was because the study was not double-blinded.

Medical therapy makes sense

“Therapy using either α-antagonists or calcium channel blockers augments the stone expulsion rate compared to standard therapy for moderately sized distal ureteral stones.” 1 CT showing distal ureteral stone

α-Antagonist studies

These 16 studies enrolled 1235 patients with distal ureteral stones. Mean stone size ranged from 4.3 to 7.8 mm. α-Antagonists improved the stone expulsion rate (RR= 1.59, 95% CI 1.44-1.75; NNT=3.3).

The mean time to expulsion of the stone ranged from 2.7 to 14.2 days and duration of therapy ranged from 1 to 7 weeks. In the 9 trials that reported the time to stone expulsion, the stone came out between 2 and 6 days earlier than the control groups.

Adverse effects were reported in 4% of patients receiving the active medication; most were mild.

Nifedipine studies

There were 686 patients in the 9 trials of nifedipine. The mean stone size was 3.9 to 12.8 mm. Some studies included stones in the more proximal as well as the distal ureter.

Nifedipine treatment increased the rate of stone expulsion (RR=1.5, 95% CI 1.34-1.68; NNT=3.9). Time to stone expulsion was shorter in 7 of the 9 studies.

Adverse effects were reported in 15% of the patients. Most of these were mild— nausea, vomiting, asthenia, and dyspepsia.

WHAT’S NEW: Strong evidence for use of medical therapy

The new findings from the Singh meta-analysis reviewed in this PURL supports physicians who have already adopted this practice and should encourage usage by those who have not yet done so.

Inpatients in academic medical centers

There is a growing trend to use tamsulosin to facilitate passage of ureteral stones. The University Health System Consortium (www.uhc.org) has complete clinical data on inpatients with ureteral stones, from 64 academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, between 2003 and 2007. We used this database to analyze trends in the use of tamsulosin in 4300 inpatients with ureteral stones (ICD 9 code 5921).

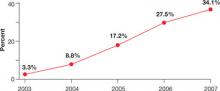

In 2003, only 3.3% of patients with a discharge diagnosis of ureteral stone received tamsulosin. In 2007, 34.1% of patients with ureteral stones discharged from these hospitals received tamsulosin, with similar rates of use when stratified by the specialty of the attending physician at discharge (family medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, urology) (FIGURE 1). We noted a wide range in the rate of adoption of this practice among academic medical centers: 48% in the centers with the highest rate of usage and 4.4% in the centers with the lowest rate.

FIGURE 1

% of inpatients in academic medical centers who received tamsulosin for ureteral stones, by year

Source: Unpublished data from the University Health System Consortium

Outpatients from a sample of US practices

The use of tamsulosin or nifedipine in outpatient practice was infrequent even 2 or 3 years ago. We used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data (www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm) from 2004 and 2005 (the most recent available), which provides a sample of all US outpatient practices. Only 7% of an estimated 1,345,000 patients diagnosed with ureteral stones were prescribed either tamsulosin or nifedipine, and urologists cared for most of those.

These unpublished data show that physicians in academic medical centers are increasingly adopting the practice of using tamsulosin or nifedipine for expulsion of ureteral stones, that urologists appear to be the first to begin using these medications in outpatients several years ago, and that this practice is being adopted actively in selected academic medical centers.

CAVEATS: Is either drug better? Too little data to tell

Our conclusion is that the strengths of this meta-analysis outweigh the weaknesses, the findings across studies are consistent, and the use of smooth-muscle relaxants for this indication makes sense from a mechanistic point of view.

The quality of a meta-analysis is only as good as the quality of the included studies, and, in this case, the overall quality of studies was not uniformly high. Median Jadad score, a summary measure of study quality, was 2, and the highest score was 3 (of a maximum of 5). The most common problem was lack of blinding, which can be critical in studies with subjective outcomes such as pain. We doubt that the lack of blinding led to any significant misclassification of outcome in this study, however.

Patients either passed the stone or they didn’t, or had a surgical intervention or not. It is reassuring that, when the best quality studies (Jadad score= 3) were analyzed separately, the results were equally good.

There have not been sufficient head-to-head trials to know if one is better than the other. We prefer α-antagonists because of the lower apparent side-effect profile. Our analysis of the UHC data shows that most of the physicians who are using medical therapy are using tamsulosin primarily for this diagnosis.

The majority of the patients in the studies included in the meta-analysis had been referred to a urologist. This raises the possibility that this treatment may not be as effective in patients with less severe symptoms for whom urological consultation is not necessary.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: This change should be easy to put into practice

Tamsulosin is the best studied of the drugs, but also the most expensive. Based on the estimated number need to treat (NNT) of between 3 and 4 to prevent a surgical intervention and an estimated cost of around $90 for 1 month (www. drugstore.com, February 16, 2008), tamsulosin seems like a good investment to avoid surgical intervention.

The evidence for the other α-antagonists is consistent with that of tamsulosin, but there are fewer data, so it is not clear that the other agents will work as well.

Many people with renal colic are diagnosed and treated in the emergency department; they may not see their family physician until some time after the stone is diagnosed. It is unclear what effect this delay might have on medication effectiveness.

Neither tamsulosin nor nifedipine have an FDA indication for ureterolithiasis. However, they are prescribed commonly, and most physicians are familiar with their use and adverse-effect profiles.

Drugs used in the meta-analysis studies

α-Antagonists

Tamsulosin (Flomax)

Terazosin (Hytrin)

Doxazosin (Cardura)

Calcium channel blockers

Nifedipine (Adalat, Nifedical, Procardia)

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Sofia Medvedev, PhD of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) in Oak Brook, IL for analysis of the UHC Clinical Database and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:552-563.

2. Teichman JM. Clinical practice. Acute renal colic from ureteral calculus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:684-693.

3. Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM. Curhan GC. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney International. 2003;63:1817-1823.

4. American Urological Association. Clinical Guidelines: Ureteral Calculi. Last updated 2007. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/uretcal07.cfm. Accessed February 11, 2008.

5. Papa L, Stiell IG, Wells GA, Ball I, Battram E, Mahoney JE. Predicting intervention in renal colic patients after emergency department evaluation. Can J Emerg Med. 2005;7:78-86.

6. Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC. Urologic Diseases of America Project. Urologic diseases in America project: urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173:848-857.

7. Morse RM, Resnick MI. Ureteral calculi: natural history and treatment in an era of advanced technology. J Urol. 1991;145:263-265.

8. Peters HJ, Eckstein W. Possible pharmacological means of treating renal colic. Urol Res. 1975;3:55-59.

9. Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Novarini A, Giannini A, Quarantelli C, et al. Nifedipine and methylpredniso-lone in facilitating ureteral stone passage: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1994;152:1095-1098.

10. Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MA, Kaufman SR, Bradford TJ, Saint S, Wei JT, et al. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:1171-1179.

Prescribe tamsulosin (typically 0.4 mg daily) or nifedipine (typically 30 mg daily) for patients with lower ureteral calculi, to speed stone passage and to avoid surgical intervention

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50:552-563.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up 2 days after he was seen in the ED and diagnosed with a distal ureteral calculus, his first. His pain is reasonably well controlled, but he has not yet passed the stone. Is there anything you can do to help him pass the stone?

Yes. Patients who are candidates for observation should be offered a trial of “medical expulsive therapy” using an α-antagonist or a calcium channel blocker. Until now, medical therapy for kidney stones consisted of pain relief only.

The ordeal of a first stone is all too common—the lifetime prevalence of kidney stones is 5.2%—and the probability of recurrence is about 50%.2,3

NHANES data show increasing prevalence between the periods 1976-1980 and 1988-1996.3 One fifth to one third of kidney stones require surgical intervention.4 In a cohort of 245 patients presenting to an ED in Canada, 50 (20%) required further procedures, including lithotripsy. Stones ≥ 6 mm in size were much less likely to pass (OR=10.7, 95% CI 4.6-24.8).5 The burden on the healthcare system is significant; there are approximately 2 million out-patient visits annually for this problem, and diagnosis and treatment costs about $2 billion annually.6

Watch and wait

The standard approach is a period of watchful waiting and pain control, with urgent urological referral for patients with evidence of upper urinary tract infection, high grade obstruction, inadequate pain or nausea control, or insufficient renal reserve.2,4 Most patients treated with watchful waiting pass their stone within 4 weeks. Any stones that don’t pass within 8 weeks are unlikely to pass spontaneously.2,7

Medical therapy has been proposed for decades

Medications that relax ureteral smooth muscle to help pass ureteral stones have been proposed for decades.8 Prior to 2000, however, only 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) of medical therapy for ureteral stones had been published.9 A subsequent meta-analysis found 9 studies and showed that medical therapy did increase the chances that a stone would pass.10 The Singh meta-analysis found 13 subsequently published studies and nearly tripled the number of patients evaluated.

STUDY SUMMARY: A well-done meta-analysis

This meta-analysis is based on 16 studies of α-antagonists (most used tamsulosin) and 9 studies of nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker.1 The studies were identified by a comprehensive search strategy that included Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register from January 1980 to January 2007. The authors included all randomized trials or controlled clinical trials of medical therapy for adults with acute ureteral colic.

The authors assessed the studies for quality using the Jadad scale, a validated scale of study quality. Higher scores represent better quality, including better documentation of randomization, blinding, and follow-up. The authors specified their planned sensitivity analyses, and used the random effects model to synthesize the results, which tends to provide a more conservative estimate of the effect.

In other words, this was a very well done meta-analysis.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria: 13 of α-antagonists, 6 of nifedipine, and 3 of both. In 13 of the 16 studies of α-antagonists, tamsulosin (Flomax) was the study drug. The results from the terazosin (Hytrin) and doxazosin (Cardura) studies were included with the tamsulosin studies. The Jadad quality scores of the 22 studies were fairly low, with a median of 2 (range of 0 to 3) on the 5-point scale. The most common deduction was because the study was not double-blinded.

Medical therapy makes sense

“Therapy using either α-antagonists or calcium channel blockers augments the stone expulsion rate compared to standard therapy for moderately sized distal ureteral stones.” 1 CT showing distal ureteral stone

α-Antagonist studies

These 16 studies enrolled 1235 patients with distal ureteral stones. Mean stone size ranged from 4.3 to 7.8 mm. α-Antagonists improved the stone expulsion rate (RR= 1.59, 95% CI 1.44-1.75; NNT=3.3).

The mean time to expulsion of the stone ranged from 2.7 to 14.2 days and duration of therapy ranged from 1 to 7 weeks. In the 9 trials that reported the time to stone expulsion, the stone came out between 2 and 6 days earlier than the control groups.

Adverse effects were reported in 4% of patients receiving the active medication; most were mild.

Nifedipine studies

There were 686 patients in the 9 trials of nifedipine. The mean stone size was 3.9 to 12.8 mm. Some studies included stones in the more proximal as well as the distal ureter.

Nifedipine treatment increased the rate of stone expulsion (RR=1.5, 95% CI 1.34-1.68; NNT=3.9). Time to stone expulsion was shorter in 7 of the 9 studies.

Adverse effects were reported in 15% of the patients. Most of these were mild— nausea, vomiting, asthenia, and dyspepsia.

WHAT’S NEW: Strong evidence for use of medical therapy

The new findings from the Singh meta-analysis reviewed in this PURL supports physicians who have already adopted this practice and should encourage usage by those who have not yet done so.

Inpatients in academic medical centers

There is a growing trend to use tamsulosin to facilitate passage of ureteral stones. The University Health System Consortium (www.uhc.org) has complete clinical data on inpatients with ureteral stones, from 64 academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, between 2003 and 2007. We used this database to analyze trends in the use of tamsulosin in 4300 inpatients with ureteral stones (ICD 9 code 5921).

In 2003, only 3.3% of patients with a discharge diagnosis of ureteral stone received tamsulosin. In 2007, 34.1% of patients with ureteral stones discharged from these hospitals received tamsulosin, with similar rates of use when stratified by the specialty of the attending physician at discharge (family medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, urology) (FIGURE 1). We noted a wide range in the rate of adoption of this practice among academic medical centers: 48% in the centers with the highest rate of usage and 4.4% in the centers with the lowest rate.

FIGURE 1

% of inpatients in academic medical centers who received tamsulosin for ureteral stones, by year

Source: Unpublished data from the University Health System Consortium

Outpatients from a sample of US practices

The use of tamsulosin or nifedipine in outpatient practice was infrequent even 2 or 3 years ago. We used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data (www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm) from 2004 and 2005 (the most recent available), which provides a sample of all US outpatient practices. Only 7% of an estimated 1,345,000 patients diagnosed with ureteral stones were prescribed either tamsulosin or nifedipine, and urologists cared for most of those.

These unpublished data show that physicians in academic medical centers are increasingly adopting the practice of using tamsulosin or nifedipine for expulsion of ureteral stones, that urologists appear to be the first to begin using these medications in outpatients several years ago, and that this practice is being adopted actively in selected academic medical centers.

CAVEATS: Is either drug better? Too little data to tell

Our conclusion is that the strengths of this meta-analysis outweigh the weaknesses, the findings across studies are consistent, and the use of smooth-muscle relaxants for this indication makes sense from a mechanistic point of view.

The quality of a meta-analysis is only as good as the quality of the included studies, and, in this case, the overall quality of studies was not uniformly high. Median Jadad score, a summary measure of study quality, was 2, and the highest score was 3 (of a maximum of 5). The most common problem was lack of blinding, which can be critical in studies with subjective outcomes such as pain. We doubt that the lack of blinding led to any significant misclassification of outcome in this study, however.

Patients either passed the stone or they didn’t, or had a surgical intervention or not. It is reassuring that, when the best quality studies (Jadad score= 3) were analyzed separately, the results were equally good.

There have not been sufficient head-to-head trials to know if one is better than the other. We prefer α-antagonists because of the lower apparent side-effect profile. Our analysis of the UHC data shows that most of the physicians who are using medical therapy are using tamsulosin primarily for this diagnosis.

The majority of the patients in the studies included in the meta-analysis had been referred to a urologist. This raises the possibility that this treatment may not be as effective in patients with less severe symptoms for whom urological consultation is not necessary.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: This change should be easy to put into practice

Tamsulosin is the best studied of the drugs, but also the most expensive. Based on the estimated number need to treat (NNT) of between 3 and 4 to prevent a surgical intervention and an estimated cost of around $90 for 1 month (www. drugstore.com, February 16, 2008), tamsulosin seems like a good investment to avoid surgical intervention.

The evidence for the other α-antagonists is consistent with that of tamsulosin, but there are fewer data, so it is not clear that the other agents will work as well.

Many people with renal colic are diagnosed and treated in the emergency department; they may not see their family physician until some time after the stone is diagnosed. It is unclear what effect this delay might have on medication effectiveness.

Neither tamsulosin nor nifedipine have an FDA indication for ureterolithiasis. However, they are prescribed commonly, and most physicians are familiar with their use and adverse-effect profiles.

Drugs used in the meta-analysis studies

α-Antagonists

Tamsulosin (Flomax)

Terazosin (Hytrin)

Doxazosin (Cardura)

Calcium channel blockers

Nifedipine (Adalat, Nifedical, Procardia)

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Sofia Medvedev, PhD of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) in Oak Brook, IL for analysis of the UHC Clinical Database and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

Prescribe tamsulosin (typically 0.4 mg daily) or nifedipine (typically 30 mg daily) for patients with lower ureteral calculi, to speed stone passage and to avoid surgical intervention

Strength of recommendation

A: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50:552-563.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up 2 days after he was seen in the ED and diagnosed with a distal ureteral calculus, his first. His pain is reasonably well controlled, but he has not yet passed the stone. Is there anything you can do to help him pass the stone?

Yes. Patients who are candidates for observation should be offered a trial of “medical expulsive therapy” using an α-antagonist or a calcium channel blocker. Until now, medical therapy for kidney stones consisted of pain relief only.

The ordeal of a first stone is all too common—the lifetime prevalence of kidney stones is 5.2%—and the probability of recurrence is about 50%.2,3

NHANES data show increasing prevalence between the periods 1976-1980 and 1988-1996.3 One fifth to one third of kidney stones require surgical intervention.4 In a cohort of 245 patients presenting to an ED in Canada, 50 (20%) required further procedures, including lithotripsy. Stones ≥ 6 mm in size were much less likely to pass (OR=10.7, 95% CI 4.6-24.8).5 The burden on the healthcare system is significant; there are approximately 2 million out-patient visits annually for this problem, and diagnosis and treatment costs about $2 billion annually.6

Watch and wait

The standard approach is a period of watchful waiting and pain control, with urgent urological referral for patients with evidence of upper urinary tract infection, high grade obstruction, inadequate pain or nausea control, or insufficient renal reserve.2,4 Most patients treated with watchful waiting pass their stone within 4 weeks. Any stones that don’t pass within 8 weeks are unlikely to pass spontaneously.2,7

Medical therapy has been proposed for decades

Medications that relax ureteral smooth muscle to help pass ureteral stones have been proposed for decades.8 Prior to 2000, however, only 1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) of medical therapy for ureteral stones had been published.9 A subsequent meta-analysis found 9 studies and showed that medical therapy did increase the chances that a stone would pass.10 The Singh meta-analysis found 13 subsequently published studies and nearly tripled the number of patients evaluated.

STUDY SUMMARY: A well-done meta-analysis

This meta-analysis is based on 16 studies of α-antagonists (most used tamsulosin) and 9 studies of nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker.1 The studies were identified by a comprehensive search strategy that included Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register from January 1980 to January 2007. The authors included all randomized trials or controlled clinical trials of medical therapy for adults with acute ureteral colic.

The authors assessed the studies for quality using the Jadad scale, a validated scale of study quality. Higher scores represent better quality, including better documentation of randomization, blinding, and follow-up. The authors specified their planned sensitivity analyses, and used the random effects model to synthesize the results, which tends to provide a more conservative estimate of the effect.

In other words, this was a very well done meta-analysis.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria: 13 of α-antagonists, 6 of nifedipine, and 3 of both. In 13 of the 16 studies of α-antagonists, tamsulosin (Flomax) was the study drug. The results from the terazosin (Hytrin) and doxazosin (Cardura) studies were included with the tamsulosin studies. The Jadad quality scores of the 22 studies were fairly low, with a median of 2 (range of 0 to 3) on the 5-point scale. The most common deduction was because the study was not double-blinded.

Medical therapy makes sense

“Therapy using either α-antagonists or calcium channel blockers augments the stone expulsion rate compared to standard therapy for moderately sized distal ureteral stones.” 1 CT showing distal ureteral stone

α-Antagonist studies

These 16 studies enrolled 1235 patients with distal ureteral stones. Mean stone size ranged from 4.3 to 7.8 mm. α-Antagonists improved the stone expulsion rate (RR= 1.59, 95% CI 1.44-1.75; NNT=3.3).

The mean time to expulsion of the stone ranged from 2.7 to 14.2 days and duration of therapy ranged from 1 to 7 weeks. In the 9 trials that reported the time to stone expulsion, the stone came out between 2 and 6 days earlier than the control groups.

Adverse effects were reported in 4% of patients receiving the active medication; most were mild.

Nifedipine studies

There were 686 patients in the 9 trials of nifedipine. The mean stone size was 3.9 to 12.8 mm. Some studies included stones in the more proximal as well as the distal ureter.

Nifedipine treatment increased the rate of stone expulsion (RR=1.5, 95% CI 1.34-1.68; NNT=3.9). Time to stone expulsion was shorter in 7 of the 9 studies.

Adverse effects were reported in 15% of the patients. Most of these were mild— nausea, vomiting, asthenia, and dyspepsia.

WHAT’S NEW: Strong evidence for use of medical therapy

The new findings from the Singh meta-analysis reviewed in this PURL supports physicians who have already adopted this practice and should encourage usage by those who have not yet done so.

Inpatients in academic medical centers

There is a growing trend to use tamsulosin to facilitate passage of ureteral stones. The University Health System Consortium (www.uhc.org) has complete clinical data on inpatients with ureteral stones, from 64 academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, between 2003 and 2007. We used this database to analyze trends in the use of tamsulosin in 4300 inpatients with ureteral stones (ICD 9 code 5921).

In 2003, only 3.3% of patients with a discharge diagnosis of ureteral stone received tamsulosin. In 2007, 34.1% of patients with ureteral stones discharged from these hospitals received tamsulosin, with similar rates of use when stratified by the specialty of the attending physician at discharge (family medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, urology) (FIGURE 1). We noted a wide range in the rate of adoption of this practice among academic medical centers: 48% in the centers with the highest rate of usage and 4.4% in the centers with the lowest rate.

FIGURE 1

% of inpatients in academic medical centers who received tamsulosin for ureteral stones, by year

Source: Unpublished data from the University Health System Consortium

Outpatients from a sample of US practices

The use of tamsulosin or nifedipine in outpatient practice was infrequent even 2 or 3 years ago. We used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data (www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm) from 2004 and 2005 (the most recent available), which provides a sample of all US outpatient practices. Only 7% of an estimated 1,345,000 patients diagnosed with ureteral stones were prescribed either tamsulosin or nifedipine, and urologists cared for most of those.

These unpublished data show that physicians in academic medical centers are increasingly adopting the practice of using tamsulosin or nifedipine for expulsion of ureteral stones, that urologists appear to be the first to begin using these medications in outpatients several years ago, and that this practice is being adopted actively in selected academic medical centers.

CAVEATS: Is either drug better? Too little data to tell

Our conclusion is that the strengths of this meta-analysis outweigh the weaknesses, the findings across studies are consistent, and the use of smooth-muscle relaxants for this indication makes sense from a mechanistic point of view.

The quality of a meta-analysis is only as good as the quality of the included studies, and, in this case, the overall quality of studies was not uniformly high. Median Jadad score, a summary measure of study quality, was 2, and the highest score was 3 (of a maximum of 5). The most common problem was lack of blinding, which can be critical in studies with subjective outcomes such as pain. We doubt that the lack of blinding led to any significant misclassification of outcome in this study, however.

Patients either passed the stone or they didn’t, or had a surgical intervention or not. It is reassuring that, when the best quality studies (Jadad score= 3) were analyzed separately, the results were equally good.

There have not been sufficient head-to-head trials to know if one is better than the other. We prefer α-antagonists because of the lower apparent side-effect profile. Our analysis of the UHC data shows that most of the physicians who are using medical therapy are using tamsulosin primarily for this diagnosis.

The majority of the patients in the studies included in the meta-analysis had been referred to a urologist. This raises the possibility that this treatment may not be as effective in patients with less severe symptoms for whom urological consultation is not necessary.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: This change should be easy to put into practice

Tamsulosin is the best studied of the drugs, but also the most expensive. Based on the estimated number need to treat (NNT) of between 3 and 4 to prevent a surgical intervention and an estimated cost of around $90 for 1 month (www. drugstore.com, February 16, 2008), tamsulosin seems like a good investment to avoid surgical intervention.

The evidence for the other α-antagonists is consistent with that of tamsulosin, but there are fewer data, so it is not clear that the other agents will work as well.

Many people with renal colic are diagnosed and treated in the emergency department; they may not see their family physician until some time after the stone is diagnosed. It is unclear what effect this delay might have on medication effectiveness.

Neither tamsulosin nor nifedipine have an FDA indication for ureterolithiasis. However, they are prescribed commonly, and most physicians are familiar with their use and adverse-effect profiles.

Drugs used in the meta-analysis studies

α-Antagonists

Tamsulosin (Flomax)

Terazosin (Hytrin)

Doxazosin (Cardura)

Calcium channel blockers

Nifedipine (Adalat, Nifedical, Procardia)

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Sofia Medvedev, PhD of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) in Oak Brook, IL for analysis of the UHC Clinical Database and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data.

PURLs methodology

This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

1. Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:552-563.

2. Teichman JM. Clinical practice. Acute renal colic from ureteral calculus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:684-693.

3. Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM. Curhan GC. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney International. 2003;63:1817-1823.

4. American Urological Association. Clinical Guidelines: Ureteral Calculi. Last updated 2007. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/uretcal07.cfm. Accessed February 11, 2008.

5. Papa L, Stiell IG, Wells GA, Ball I, Battram E, Mahoney JE. Predicting intervention in renal colic patients after emergency department evaluation. Can J Emerg Med. 2005;7:78-86.

6. Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC. Urologic Diseases of America Project. Urologic diseases in America project: urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173:848-857.

7. Morse RM, Resnick MI. Ureteral calculi: natural history and treatment in an era of advanced technology. J Urol. 1991;145:263-265.

8. Peters HJ, Eckstein W. Possible pharmacological means of treating renal colic. Urol Res. 1975;3:55-59.

9. Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Novarini A, Giannini A, Quarantelli C, et al. Nifedipine and methylpredniso-lone in facilitating ureteral stone passage: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1994;152:1095-1098.

10. Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MA, Kaufman SR, Bradford TJ, Saint S, Wei JT, et al. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:1171-1179.

1. Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:552-563.

2. Teichman JM. Clinical practice. Acute renal colic from ureteral calculus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:684-693.

3. Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM. Curhan GC. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney International. 2003;63:1817-1823.

4. American Urological Association. Clinical Guidelines: Ureteral Calculi. Last updated 2007. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/uretcal07.cfm. Accessed February 11, 2008.

5. Papa L, Stiell IG, Wells GA, Ball I, Battram E, Mahoney JE. Predicting intervention in renal colic patients after emergency department evaluation. Can J Emerg Med. 2005;7:78-86.

6. Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC. Urologic Diseases of America Project. Urologic diseases in America project: urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173:848-857.

7. Morse RM, Resnick MI. Ureteral calculi: natural history and treatment in an era of advanced technology. J Urol. 1991;145:263-265.

8. Peters HJ, Eckstein W. Possible pharmacological means of treating renal colic. Urol Res. 1975;3:55-59.

9. Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Novarini A, Giannini A, Quarantelli C, et al. Nifedipine and methylpredniso-lone in facilitating ureteral stone passage: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1994;152:1095-1098.

10. Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MA, Kaufman SR, Bradford TJ, Saint S, Wei JT, et al. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:1171-1179.

Copyright © 2008 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.