User login

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

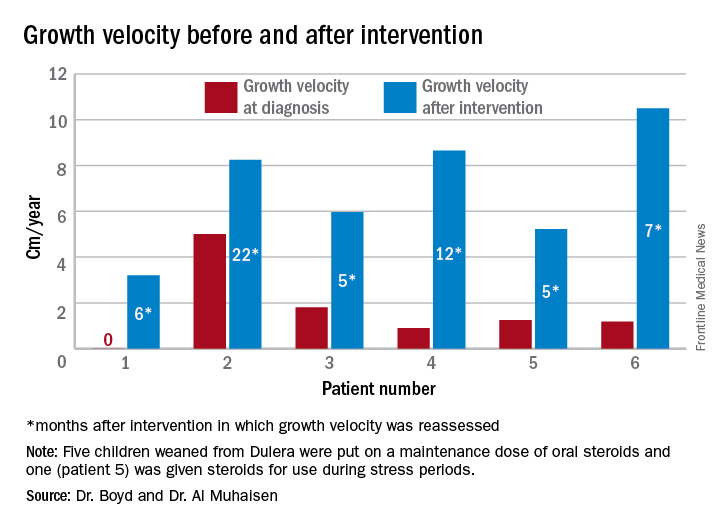

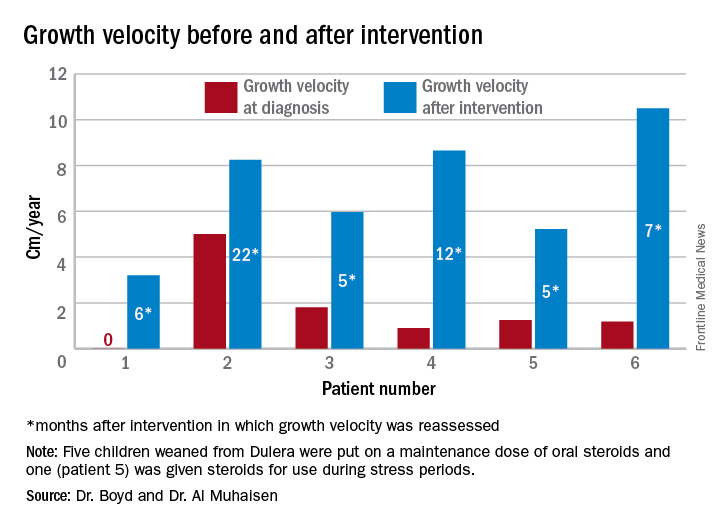

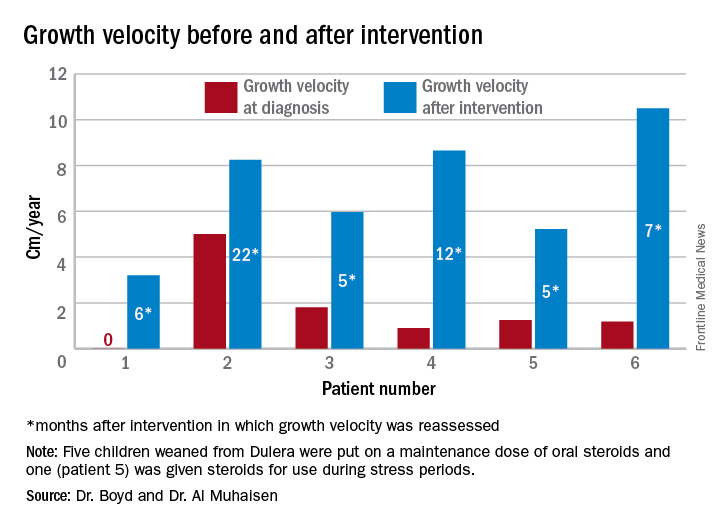

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of eight children who had an adrenal workup at an endocrinology clinic, six had adrenal suppression.

Data source: The case series comprised 18 children taking Dulera who presented with growth failure.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.