User login

SAN FRANCISCO –

Federal laws require those handling sensitive health information to have policies and security safeguards in place to protect such information, whether it’s stored on paper or electronically.

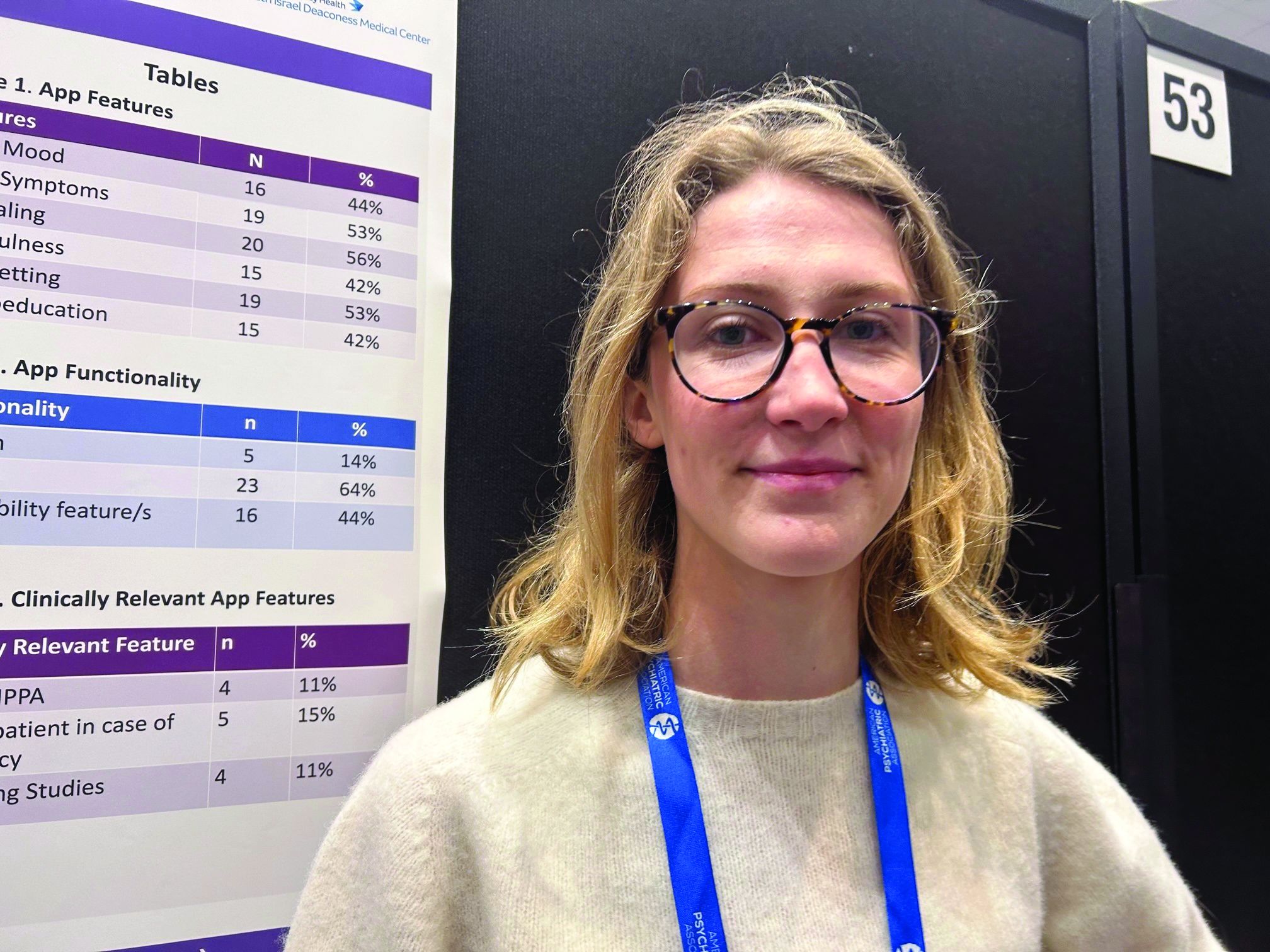

“As it stands right now, there’s not enough evidence to support using these apps as an adjunct to clinical care,” study author Theodora O’Leary, a 4th-year medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “We need more research on the efficacy of these apps because right now not enough of them meet HIPAA [standards] and don’t have privacy and security measures.”

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Eating disorders (EDs) are a common mental health condition affecting almost 1 in 10 Americans over their lifetime. Yet only about a third of patients with an eating disorder receive adequate treatment.

The pandemic saw a rise in eating disorders and in the use of mental health apps “to kind of fill the gap because people couldn’t be seen in person,” said Ms. O’Leary.

Inexpensive and accessible

Smartphone apps have a lot of advantages for patients with an ED. For one thing, they’re relatively inexpensive and accessible; most Americans already own one or more devices on which these apps can be used.

They’re also a feasible means of delivering psychological interventions, which are often recommended for EDs. Among these interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the largest evidence base for this condition.

Also, as many individuals with an ED may be reluctant to seek treatment because of stigma and shame, the anonymity afforded by an app could increase access to the help they seek.

But Ms. O’Leary warned the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate these apps, and people are sharing their personal health information on them.

The researchers conducted a review of commercially available eating disorder apps by searching the Apple and Google play stores using key phrases such as “eating disorder,” “anorexia,” and “binge eating disorder.”

They found 16 relevant apps that they added to the publicly available apps already in a database at Tufts, for a total of about 36 that were evaluated in the study (the number fluctuates as apps are deleted.)

They then reviewed the apps using the 105 questions based on the APA’s app evaluation model, which covers categories such as efficacy, privacy, accessibility, and clinical applicability. And they used filters to group apps by characteristics such as function, cost, and features.

The vast majority were self-help apps, which include things like journaling, meditation, and information on CBT. Others were reference apps that provide related definitions and sometimes include surveys to determine, for example, if the user has an eating disorder.

About 44% of the apps track mood, and 53% track symptoms. Some 56% include journaling, 42% mindfulness, 53% goal setting, and 42% psychoeducation.

Hybrid care

Only 5% of apps allow for “hybrid” care. This, explained Ms. O’Leary, is when clinicians use their own app to access patients’ apps, allowing them to track food restrictions and therapies, and make comments.

“The hybrid is viewed as the best form of app”, she said. “It’s almost like an adjunct to clinical care.”

Hybrid apps also tend to have patient safety features, she added. And these apps meet HIPAA standards, which only 11% of the apps in the study did.

Only 15% of apps advised patients to take steps in case of an emergency, and 11% had supporting studies. And where there was supporting research, much of it was funded by the app creators, said Ms. O’Leary.

For example, an app provided by Noom (the weight loss program that promises to help change habits and mindsets around food) “has a bunch of feasibility studies but they’re all funded by Noom”, which can introduce bias, she explained.

None of the apps were created by an accredited health care institution, she noted. “And I think only one app out of all the eating disorder apps we looked at was from a nonprofit.”

About 17% of the apps offer help with a “coach” or “expert”. However, these apps often fail to disclose the definition of a coach or state they’re not a replacement for medical care.

Coaching apps more expensive

Additionally, these coaching apps are often some of the most expensive, said Ms. O’Leary.

Daniel E. Gih, MD, associate professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, helped start an eating disorders program at the University of Michigan and continues to treat patients with eating disorders. He said the increase in the use of eating disorder apps isn’t surprising as the incidence of these disorders increased in the wake of pandemic restrictions, especially among young people.

“Patients are likely doing more research on their medical conditions and trying to crowdsource information or self-treat,” Dr. Gih said.

It’s unclear whether “shame or just the general lack of specialized eating disorder professionals,” including physicians, is driving some of the interest in these apps, he added.

Dr. Gih stressed eating disorder apps should not only include screening for suicidality, but also explicitly tell patients to seek immediate attention if they show certain signs – for example, fainting, chest pain, or blood in emesis.

“The apps may be giving patients false hope or delaying medical care,” he said. “Apps are likely not sufficient enough to replace a multidisciplinary team with experience and expertise in eating disorders.”

Ms. O’Leary and Dr. Gih report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO –

Federal laws require those handling sensitive health information to have policies and security safeguards in place to protect such information, whether it’s stored on paper or electronically.

“As it stands right now, there’s not enough evidence to support using these apps as an adjunct to clinical care,” study author Theodora O’Leary, a 4th-year medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “We need more research on the efficacy of these apps because right now not enough of them meet HIPAA [standards] and don’t have privacy and security measures.”

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Eating disorders (EDs) are a common mental health condition affecting almost 1 in 10 Americans over their lifetime. Yet only about a third of patients with an eating disorder receive adequate treatment.

The pandemic saw a rise in eating disorders and in the use of mental health apps “to kind of fill the gap because people couldn’t be seen in person,” said Ms. O’Leary.

Inexpensive and accessible

Smartphone apps have a lot of advantages for patients with an ED. For one thing, they’re relatively inexpensive and accessible; most Americans already own one or more devices on which these apps can be used.

They’re also a feasible means of delivering psychological interventions, which are often recommended for EDs. Among these interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the largest evidence base for this condition.

Also, as many individuals with an ED may be reluctant to seek treatment because of stigma and shame, the anonymity afforded by an app could increase access to the help they seek.

But Ms. O’Leary warned the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate these apps, and people are sharing their personal health information on them.

The researchers conducted a review of commercially available eating disorder apps by searching the Apple and Google play stores using key phrases such as “eating disorder,” “anorexia,” and “binge eating disorder.”

They found 16 relevant apps that they added to the publicly available apps already in a database at Tufts, for a total of about 36 that were evaluated in the study (the number fluctuates as apps are deleted.)

They then reviewed the apps using the 105 questions based on the APA’s app evaluation model, which covers categories such as efficacy, privacy, accessibility, and clinical applicability. And they used filters to group apps by characteristics such as function, cost, and features.

The vast majority were self-help apps, which include things like journaling, meditation, and information on CBT. Others were reference apps that provide related definitions and sometimes include surveys to determine, for example, if the user has an eating disorder.

About 44% of the apps track mood, and 53% track symptoms. Some 56% include journaling, 42% mindfulness, 53% goal setting, and 42% psychoeducation.

Hybrid care

Only 5% of apps allow for “hybrid” care. This, explained Ms. O’Leary, is when clinicians use their own app to access patients’ apps, allowing them to track food restrictions and therapies, and make comments.

“The hybrid is viewed as the best form of app”, she said. “It’s almost like an adjunct to clinical care.”

Hybrid apps also tend to have patient safety features, she added. And these apps meet HIPAA standards, which only 11% of the apps in the study did.

Only 15% of apps advised patients to take steps in case of an emergency, and 11% had supporting studies. And where there was supporting research, much of it was funded by the app creators, said Ms. O’Leary.

For example, an app provided by Noom (the weight loss program that promises to help change habits and mindsets around food) “has a bunch of feasibility studies but they’re all funded by Noom”, which can introduce bias, she explained.

None of the apps were created by an accredited health care institution, she noted. “And I think only one app out of all the eating disorder apps we looked at was from a nonprofit.”

About 17% of the apps offer help with a “coach” or “expert”. However, these apps often fail to disclose the definition of a coach or state they’re not a replacement for medical care.

Coaching apps more expensive

Additionally, these coaching apps are often some of the most expensive, said Ms. O’Leary.

Daniel E. Gih, MD, associate professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, helped start an eating disorders program at the University of Michigan and continues to treat patients with eating disorders. He said the increase in the use of eating disorder apps isn’t surprising as the incidence of these disorders increased in the wake of pandemic restrictions, especially among young people.

“Patients are likely doing more research on their medical conditions and trying to crowdsource information or self-treat,” Dr. Gih said.

It’s unclear whether “shame or just the general lack of specialized eating disorder professionals,” including physicians, is driving some of the interest in these apps, he added.

Dr. Gih stressed eating disorder apps should not only include screening for suicidality, but also explicitly tell patients to seek immediate attention if they show certain signs – for example, fainting, chest pain, or blood in emesis.

“The apps may be giving patients false hope or delaying medical care,” he said. “Apps are likely not sufficient enough to replace a multidisciplinary team with experience and expertise in eating disorders.”

Ms. O’Leary and Dr. Gih report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO –

Federal laws require those handling sensitive health information to have policies and security safeguards in place to protect such information, whether it’s stored on paper or electronically.

“As it stands right now, there’s not enough evidence to support using these apps as an adjunct to clinical care,” study author Theodora O’Leary, a 4th-year medical student at Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview. “We need more research on the efficacy of these apps because right now not enough of them meet HIPAA [standards] and don’t have privacy and security measures.”

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Eating disorders (EDs) are a common mental health condition affecting almost 1 in 10 Americans over their lifetime. Yet only about a third of patients with an eating disorder receive adequate treatment.

The pandemic saw a rise in eating disorders and in the use of mental health apps “to kind of fill the gap because people couldn’t be seen in person,” said Ms. O’Leary.

Inexpensive and accessible

Smartphone apps have a lot of advantages for patients with an ED. For one thing, they’re relatively inexpensive and accessible; most Americans already own one or more devices on which these apps can be used.

They’re also a feasible means of delivering psychological interventions, which are often recommended for EDs. Among these interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the largest evidence base for this condition.

Also, as many individuals with an ED may be reluctant to seek treatment because of stigma and shame, the anonymity afforded by an app could increase access to the help they seek.

But Ms. O’Leary warned the Food and Drug Administration does not regulate these apps, and people are sharing their personal health information on them.

The researchers conducted a review of commercially available eating disorder apps by searching the Apple and Google play stores using key phrases such as “eating disorder,” “anorexia,” and “binge eating disorder.”

They found 16 relevant apps that they added to the publicly available apps already in a database at Tufts, for a total of about 36 that were evaluated in the study (the number fluctuates as apps are deleted.)

They then reviewed the apps using the 105 questions based on the APA’s app evaluation model, which covers categories such as efficacy, privacy, accessibility, and clinical applicability. And they used filters to group apps by characteristics such as function, cost, and features.

The vast majority were self-help apps, which include things like journaling, meditation, and information on CBT. Others were reference apps that provide related definitions and sometimes include surveys to determine, for example, if the user has an eating disorder.

About 44% of the apps track mood, and 53% track symptoms. Some 56% include journaling, 42% mindfulness, 53% goal setting, and 42% psychoeducation.

Hybrid care

Only 5% of apps allow for “hybrid” care. This, explained Ms. O’Leary, is when clinicians use their own app to access patients’ apps, allowing them to track food restrictions and therapies, and make comments.

“The hybrid is viewed as the best form of app”, she said. “It’s almost like an adjunct to clinical care.”

Hybrid apps also tend to have patient safety features, she added. And these apps meet HIPAA standards, which only 11% of the apps in the study did.

Only 15% of apps advised patients to take steps in case of an emergency, and 11% had supporting studies. And where there was supporting research, much of it was funded by the app creators, said Ms. O’Leary.

For example, an app provided by Noom (the weight loss program that promises to help change habits and mindsets around food) “has a bunch of feasibility studies but they’re all funded by Noom”, which can introduce bias, she explained.

None of the apps were created by an accredited health care institution, she noted. “And I think only one app out of all the eating disorder apps we looked at was from a nonprofit.”

About 17% of the apps offer help with a “coach” or “expert”. However, these apps often fail to disclose the definition of a coach or state they’re not a replacement for medical care.

Coaching apps more expensive

Additionally, these coaching apps are often some of the most expensive, said Ms. O’Leary.

Daniel E. Gih, MD, associate professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, helped start an eating disorders program at the University of Michigan and continues to treat patients with eating disorders. He said the increase in the use of eating disorder apps isn’t surprising as the incidence of these disorders increased in the wake of pandemic restrictions, especially among young people.

“Patients are likely doing more research on their medical conditions and trying to crowdsource information or self-treat,” Dr. Gih said.

It’s unclear whether “shame or just the general lack of specialized eating disorder professionals,” including physicians, is driving some of the interest in these apps, he added.

Dr. Gih stressed eating disorder apps should not only include screening for suicidality, but also explicitly tell patients to seek immediate attention if they show certain signs – for example, fainting, chest pain, or blood in emesis.

“The apps may be giving patients false hope or delaying medical care,” he said. “Apps are likely not sufficient enough to replace a multidisciplinary team with experience and expertise in eating disorders.”

Ms. O’Leary and Dr. Gih report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT APA 2023