User login

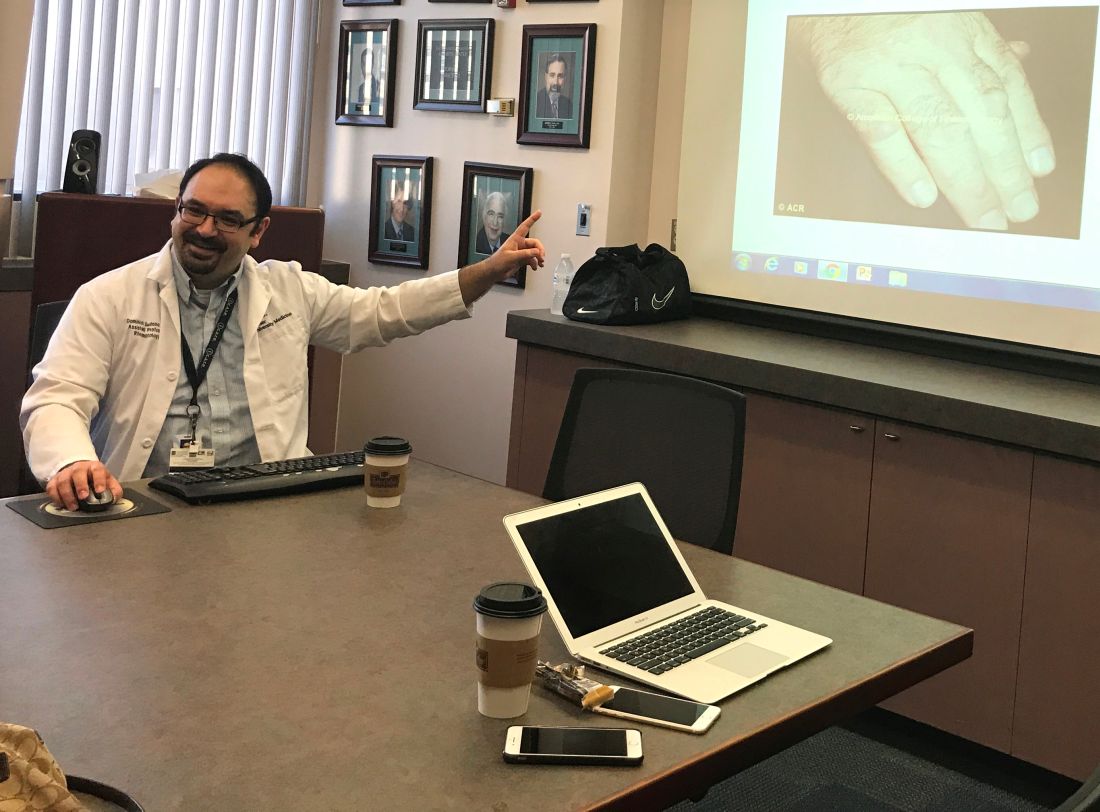

As in many places throughout the country, rheumatologists are in short supply in southern Arizona. Patients frequently wait up to 6 months to visit a rheumatologist at Banner University Medical Center (BUMC) in Tucson, and many drive between 3 and 4 hours for the appointment, said Dominick G. Sudano, MD, a rheumatologist at BUMC, which is affiliated with the University of Arizona.

[polldaddy:9823712]

The high demand for rheumatologists and lack of timely access led the University of Arizona to develop a program that will train primary care providers at remote sites to treat rheumatic diseases. The program, a partnership between the university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program and the University of Arizona Center for Rural Health, will use the popular ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model, founded by the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, which aims to increase workforce capacity by sharing medical knowledge.

A unique model of care

As part of the program, set to launch this month, Dr. Sudano will hold rheumatology training sessions via telemedicine for primary care physicians and other nonphysicians at four remote sites around Arizona. Participating sites include Canyonlands Healthcare, North County Healthcare, and Northern Arizona Healthcare – all located in the northern part of the state – and Copper Queen Community Hospital in southern Arizona.

The virtual sessions will include both educational topics and the opportunity for local doctors and health professionals to present patient cases to Dr. Sudano for guidance. The local doctors and health professionals will eventually treat rheumatic cases in their communities, while cases identified as severe will still be referred to rheumatologists.

The university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program was fortunate to receive a $17,700 grant from Lilly to launch the 1-year rheumatology ECHO pilot program, Dr. Sudano noted. The grant will enable the program to get off the ground, while administrators search for additional funding sources to become sustainable, he said.

Dr. Sudano credits the assistance and support of the University of New Mexico and its ECHO leaders for helping the University of Arizona build its ECHO rheumatology program and helping administrators address the details of setting up the program.

“[The University of New Mexico] was immensely helpful,” he said. “They have immersion sessions about once a month and you spend [time] working with their team. They work with you to get the logistics ironed out.”

A spreading movement

The University of New Mexico (UNM) has good reason to assist other health and academic medical centers in launching their own ECHO programs. UNM’s mission is to continue building the ECHO movement and accomplish its goal of “touching 1 billion lives” by 2025, said Sanjeev Arora, MD, a gastroenterologist at UNM and founder/director of the university’s Project ECHO.

“There was a great shortage of specialists to treat hepatitis C so I came up with this idea of ECHO to bring access to care to everyone in New Mexico who needed care,” he said. “The second part of the idea was, if we could do that for hepatitis C, we could do that for a lot of other problems like rheumatoid arthritis, like addiction, like diabetes.”

Project ECHO has now spread to medical centers and hospitals across the country, with programs that center on asthma, HIV infection, cardiac risk reduction, chronic pain management, geriatrics, palliative care, substance abuse, and obesity, among others. The model is now in 139 academic hubs in 24 countries with more than 65 health conditions targeted, according to Dr. Arora. Replication sites focus on four key principles of ECHO: technology used to leverage scarce health care expertise and resources; best practices shared to standardize care across disparate health care delivery systems; case-based learning used as the primary modality to build knowledge, confidence, and expertise; and evaluations conducted to monitor outcomes.

Data show the care patients receive via the ECHO model is equal to that of care provided by university-based specialists. A 2011 report published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that a sustained viral response to treatment for hepatitis C was achieved in 58% of patients managed at the university and by 58% of patients managed by primary care physicians at rural and prison sites who participated in Project ECHO (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199-2207). Response rates to different subtypes of hepatitis C also did not differ significantly between the two groups.

The ECHO model has also greatly improved access and outcomes for hepatitis C patients in Northern Arizona, said Colleen Hopkins, telehealth coordinator at North Country Healthcare in Flagstaff. North Country Healthcare has participated in a hepatitis C ECHO program since 2012, linking its chain of 14 community health centers with a hepatologist-educator at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, 140 miles to the south.

“In 2011, more than 950 patients in the health system’s network had a hepatitis C diagnosis, but the majority did not have access to care,” Ms. Hopkins said in an interview.

“To date, over 500 patients have received care for their liver disease in rural Northern Arizona,” she said. “These numbers continue to climb as our awareness has caused an increase in screening and various outreach efforts ... Overall, our providers and patients are empowered by having access to specialty care; they are living longer healthier lives as well as keeping money in our communities.”

Rheumatology and the ECHO model

The volume of rheumatic conditions encountered by primary care physicians and the shortage of specialists make rheumatology a logical fit for the ECHO model, Dr. Arora said. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, and joint pain account for as many as one in five visits to primary care doctors, he noted.

“Osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis produce massive disability in the world,” he said. “Treatment exists, but it’s not getting to patients. ECHO can fundamentally transform the field of rheumatology if it’s adopted widely.”

However, compared with other specialty ECHO models, there are not many rheumatology ECHO programs in operation. Dr. Arora is hopeful that as word spreads about how well rheumatology fits into the ECHO structure, more programs will develop, he said.

“We have found over the years that with our training these providers – both physicians and nonphysician – are able to function as well as a specially trained [rheumatologist],” Dr. Bankhurst said. “We help them as needed by our weekly teleconference where they present cases to us and those cases which appear to be most difficult, we see immediately in our clinics.”

The program has led to decreased referrals to the university from outlying areas and more care access for patients in rural areas, Dr. Bankhurst said. A university study is underway to analyze clinical outcomes for rheumatoid arthritis as conducted by distant provider sites compared with treatment at the university clinic.

“It’s my perspective, based on 12 years of experience, that they’ll be identical,” he said.

Setting up such ECHO programs is not without challenges. Financial support for telecommunication equipment in all needed areas can be difficult, Dr. Bankhurst said. Recruiting individuals who are well motivated to participate in the program can also be a challenge.

“It needs a commitment by the administration,” he said. “It does take time from other activities. It requires dedicated time away from a busy clinic.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

As in many places throughout the country, rheumatologists are in short supply in southern Arizona. Patients frequently wait up to 6 months to visit a rheumatologist at Banner University Medical Center (BUMC) in Tucson, and many drive between 3 and 4 hours for the appointment, said Dominick G. Sudano, MD, a rheumatologist at BUMC, which is affiliated with the University of Arizona.

[polldaddy:9823712]

The high demand for rheumatologists and lack of timely access led the University of Arizona to develop a program that will train primary care providers at remote sites to treat rheumatic diseases. The program, a partnership between the university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program and the University of Arizona Center for Rural Health, will use the popular ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model, founded by the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, which aims to increase workforce capacity by sharing medical knowledge.

A unique model of care

As part of the program, set to launch this month, Dr. Sudano will hold rheumatology training sessions via telemedicine for primary care physicians and other nonphysicians at four remote sites around Arizona. Participating sites include Canyonlands Healthcare, North County Healthcare, and Northern Arizona Healthcare – all located in the northern part of the state – and Copper Queen Community Hospital in southern Arizona.

The virtual sessions will include both educational topics and the opportunity for local doctors and health professionals to present patient cases to Dr. Sudano for guidance. The local doctors and health professionals will eventually treat rheumatic cases in their communities, while cases identified as severe will still be referred to rheumatologists.

The university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program was fortunate to receive a $17,700 grant from Lilly to launch the 1-year rheumatology ECHO pilot program, Dr. Sudano noted. The grant will enable the program to get off the ground, while administrators search for additional funding sources to become sustainable, he said.

Dr. Sudano credits the assistance and support of the University of New Mexico and its ECHO leaders for helping the University of Arizona build its ECHO rheumatology program and helping administrators address the details of setting up the program.

“[The University of New Mexico] was immensely helpful,” he said. “They have immersion sessions about once a month and you spend [time] working with their team. They work with you to get the logistics ironed out.”

A spreading movement

The University of New Mexico (UNM) has good reason to assist other health and academic medical centers in launching their own ECHO programs. UNM’s mission is to continue building the ECHO movement and accomplish its goal of “touching 1 billion lives” by 2025, said Sanjeev Arora, MD, a gastroenterologist at UNM and founder/director of the university’s Project ECHO.

“There was a great shortage of specialists to treat hepatitis C so I came up with this idea of ECHO to bring access to care to everyone in New Mexico who needed care,” he said. “The second part of the idea was, if we could do that for hepatitis C, we could do that for a lot of other problems like rheumatoid arthritis, like addiction, like diabetes.”

Project ECHO has now spread to medical centers and hospitals across the country, with programs that center on asthma, HIV infection, cardiac risk reduction, chronic pain management, geriatrics, palliative care, substance abuse, and obesity, among others. The model is now in 139 academic hubs in 24 countries with more than 65 health conditions targeted, according to Dr. Arora. Replication sites focus on four key principles of ECHO: technology used to leverage scarce health care expertise and resources; best practices shared to standardize care across disparate health care delivery systems; case-based learning used as the primary modality to build knowledge, confidence, and expertise; and evaluations conducted to monitor outcomes.

Data show the care patients receive via the ECHO model is equal to that of care provided by university-based specialists. A 2011 report published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that a sustained viral response to treatment for hepatitis C was achieved in 58% of patients managed at the university and by 58% of patients managed by primary care physicians at rural and prison sites who participated in Project ECHO (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199-2207). Response rates to different subtypes of hepatitis C also did not differ significantly between the two groups.

The ECHO model has also greatly improved access and outcomes for hepatitis C patients in Northern Arizona, said Colleen Hopkins, telehealth coordinator at North Country Healthcare in Flagstaff. North Country Healthcare has participated in a hepatitis C ECHO program since 2012, linking its chain of 14 community health centers with a hepatologist-educator at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, 140 miles to the south.

“In 2011, more than 950 patients in the health system’s network had a hepatitis C diagnosis, but the majority did not have access to care,” Ms. Hopkins said in an interview.

“To date, over 500 patients have received care for their liver disease in rural Northern Arizona,” she said. “These numbers continue to climb as our awareness has caused an increase in screening and various outreach efforts ... Overall, our providers and patients are empowered by having access to specialty care; they are living longer healthier lives as well as keeping money in our communities.”

Rheumatology and the ECHO model

The volume of rheumatic conditions encountered by primary care physicians and the shortage of specialists make rheumatology a logical fit for the ECHO model, Dr. Arora said. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, and joint pain account for as many as one in five visits to primary care doctors, he noted.

“Osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis produce massive disability in the world,” he said. “Treatment exists, but it’s not getting to patients. ECHO can fundamentally transform the field of rheumatology if it’s adopted widely.”

However, compared with other specialty ECHO models, there are not many rheumatology ECHO programs in operation. Dr. Arora is hopeful that as word spreads about how well rheumatology fits into the ECHO structure, more programs will develop, he said.

“We have found over the years that with our training these providers – both physicians and nonphysician – are able to function as well as a specially trained [rheumatologist],” Dr. Bankhurst said. “We help them as needed by our weekly teleconference where they present cases to us and those cases which appear to be most difficult, we see immediately in our clinics.”

The program has led to decreased referrals to the university from outlying areas and more care access for patients in rural areas, Dr. Bankhurst said. A university study is underway to analyze clinical outcomes for rheumatoid arthritis as conducted by distant provider sites compared with treatment at the university clinic.

“It’s my perspective, based on 12 years of experience, that they’ll be identical,” he said.

Setting up such ECHO programs is not without challenges. Financial support for telecommunication equipment in all needed areas can be difficult, Dr. Bankhurst said. Recruiting individuals who are well motivated to participate in the program can also be a challenge.

“It needs a commitment by the administration,” he said. “It does take time from other activities. It requires dedicated time away from a busy clinic.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

As in many places throughout the country, rheumatologists are in short supply in southern Arizona. Patients frequently wait up to 6 months to visit a rheumatologist at Banner University Medical Center (BUMC) in Tucson, and many drive between 3 and 4 hours for the appointment, said Dominick G. Sudano, MD, a rheumatologist at BUMC, which is affiliated with the University of Arizona.

[polldaddy:9823712]

The high demand for rheumatologists and lack of timely access led the University of Arizona to develop a program that will train primary care providers at remote sites to treat rheumatic diseases. The program, a partnership between the university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program and the University of Arizona Center for Rural Health, will use the popular ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model, founded by the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, which aims to increase workforce capacity by sharing medical knowledge.

A unique model of care

As part of the program, set to launch this month, Dr. Sudano will hold rheumatology training sessions via telemedicine for primary care physicians and other nonphysicians at four remote sites around Arizona. Participating sites include Canyonlands Healthcare, North County Healthcare, and Northern Arizona Healthcare – all located in the northern part of the state – and Copper Queen Community Hospital in southern Arizona.

The virtual sessions will include both educational topics and the opportunity for local doctors and health professionals to present patient cases to Dr. Sudano for guidance. The local doctors and health professionals will eventually treat rheumatic cases in their communities, while cases identified as severe will still be referred to rheumatologists.

The university’s Arizona Telemedicine Program was fortunate to receive a $17,700 grant from Lilly to launch the 1-year rheumatology ECHO pilot program, Dr. Sudano noted. The grant will enable the program to get off the ground, while administrators search for additional funding sources to become sustainable, he said.

Dr. Sudano credits the assistance and support of the University of New Mexico and its ECHO leaders for helping the University of Arizona build its ECHO rheumatology program and helping administrators address the details of setting up the program.

“[The University of New Mexico] was immensely helpful,” he said. “They have immersion sessions about once a month and you spend [time] working with their team. They work with you to get the logistics ironed out.”

A spreading movement

The University of New Mexico (UNM) has good reason to assist other health and academic medical centers in launching their own ECHO programs. UNM’s mission is to continue building the ECHO movement and accomplish its goal of “touching 1 billion lives” by 2025, said Sanjeev Arora, MD, a gastroenterologist at UNM and founder/director of the university’s Project ECHO.

“There was a great shortage of specialists to treat hepatitis C so I came up with this idea of ECHO to bring access to care to everyone in New Mexico who needed care,” he said. “The second part of the idea was, if we could do that for hepatitis C, we could do that for a lot of other problems like rheumatoid arthritis, like addiction, like diabetes.”

Project ECHO has now spread to medical centers and hospitals across the country, with programs that center on asthma, HIV infection, cardiac risk reduction, chronic pain management, geriatrics, palliative care, substance abuse, and obesity, among others. The model is now in 139 academic hubs in 24 countries with more than 65 health conditions targeted, according to Dr. Arora. Replication sites focus on four key principles of ECHO: technology used to leverage scarce health care expertise and resources; best practices shared to standardize care across disparate health care delivery systems; case-based learning used as the primary modality to build knowledge, confidence, and expertise; and evaluations conducted to monitor outcomes.

Data show the care patients receive via the ECHO model is equal to that of care provided by university-based specialists. A 2011 report published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that a sustained viral response to treatment for hepatitis C was achieved in 58% of patients managed at the university and by 58% of patients managed by primary care physicians at rural and prison sites who participated in Project ECHO (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199-2207). Response rates to different subtypes of hepatitis C also did not differ significantly between the two groups.

The ECHO model has also greatly improved access and outcomes for hepatitis C patients in Northern Arizona, said Colleen Hopkins, telehealth coordinator at North Country Healthcare in Flagstaff. North Country Healthcare has participated in a hepatitis C ECHO program since 2012, linking its chain of 14 community health centers with a hepatologist-educator at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, 140 miles to the south.

“In 2011, more than 950 patients in the health system’s network had a hepatitis C diagnosis, but the majority did not have access to care,” Ms. Hopkins said in an interview.

“To date, over 500 patients have received care for their liver disease in rural Northern Arizona,” she said. “These numbers continue to climb as our awareness has caused an increase in screening and various outreach efforts ... Overall, our providers and patients are empowered by having access to specialty care; they are living longer healthier lives as well as keeping money in our communities.”

Rheumatology and the ECHO model

The volume of rheumatic conditions encountered by primary care physicians and the shortage of specialists make rheumatology a logical fit for the ECHO model, Dr. Arora said. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, fibromyalgia, and joint pain account for as many as one in five visits to primary care doctors, he noted.

“Osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis produce massive disability in the world,” he said. “Treatment exists, but it’s not getting to patients. ECHO can fundamentally transform the field of rheumatology if it’s adopted widely.”

However, compared with other specialty ECHO models, there are not many rheumatology ECHO programs in operation. Dr. Arora is hopeful that as word spreads about how well rheumatology fits into the ECHO structure, more programs will develop, he said.

“We have found over the years that with our training these providers – both physicians and nonphysician – are able to function as well as a specially trained [rheumatologist],” Dr. Bankhurst said. “We help them as needed by our weekly teleconference where they present cases to us and those cases which appear to be most difficult, we see immediately in our clinics.”

The program has led to decreased referrals to the university from outlying areas and more care access for patients in rural areas, Dr. Bankhurst said. A university study is underway to analyze clinical outcomes for rheumatoid arthritis as conducted by distant provider sites compared with treatment at the university clinic.

“It’s my perspective, based on 12 years of experience, that they’ll be identical,” he said.

Setting up such ECHO programs is not without challenges. Financial support for telecommunication equipment in all needed areas can be difficult, Dr. Bankhurst said. Recruiting individuals who are well motivated to participate in the program can also be a challenge.

“It needs a commitment by the administration,” he said. “It does take time from other activities. It requires dedicated time away from a busy clinic.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med