User login

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

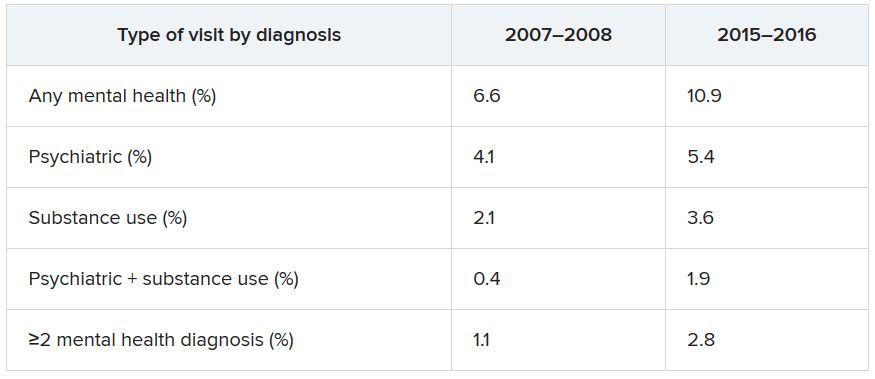

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

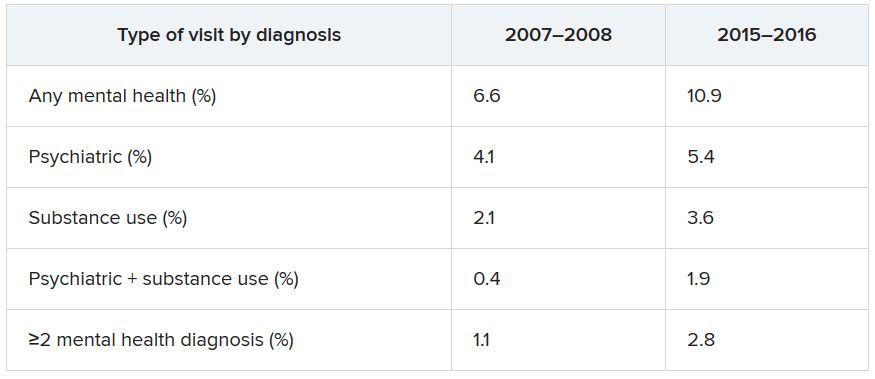

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

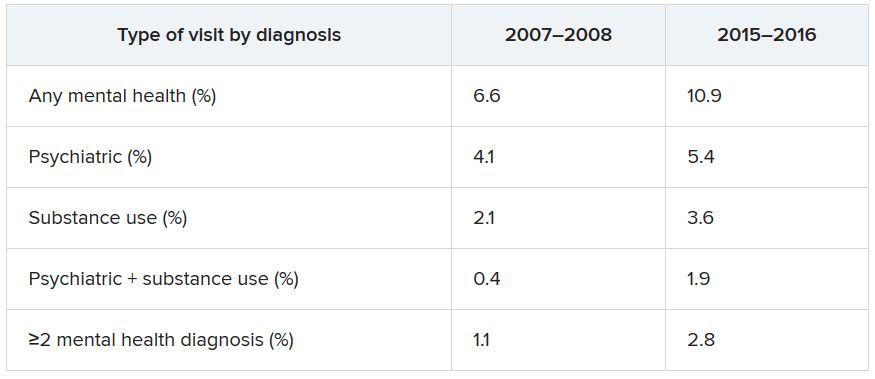

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.