User login

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

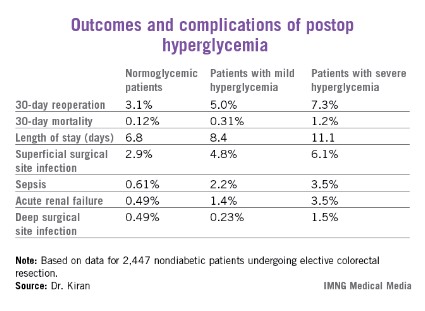

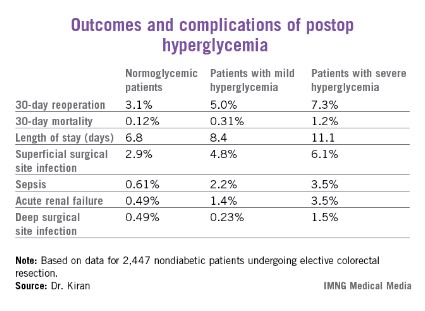

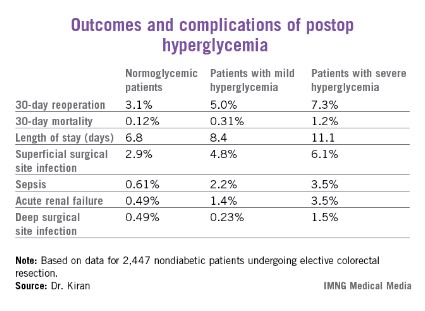

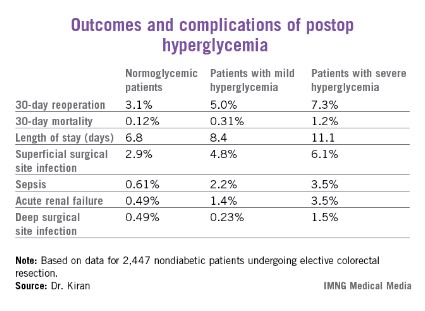

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Even a single brief episode of postoperative hyperglycemia after colorectal resection in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in a large consecutive patient series.

The risks of a variety of complications, both infectious and noninfectious, in nondiabetic patients with postoperative hyperglycemia were similar in magnitude to those seen in diabetic patients experiencing postoperative hyperglycemia.

"A take-home point from our study would be that since it’s known that in diabetic patients it’s absolutely paramount to control hyperglycemia, perhaps nondiabetic patients undergoing major operations – especially colorectal surgery – need to be carefully monitored and have their glucose managed," Dr. P. Ravi Kiran said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He and his coinvestigators evaluated the significance of hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours postoperatively in 2,628 consecutive patients undergoing elective colorectal resection at the Cleveland Clinic in a recent 2-year period.

A total of 2,447 of these patients were nondiabetic. They collectively had 16,404 randomly obtained postoperative blood glucose measurements. One-third of them remained normoglycemic, with all their blood glucose values remaining at 125 mg/dL or less. Another 52.7% had one or more episodes of mild hyperglycemia as defined by a blood glucose value of 126-200 mg/dL. And 14% of nondiabetic subjects experienced postoperative severe hyperglycemia, with a level in excess of 200 mg/dL.

Those rates were similar to those of the known-diabetic patients, 35% of whom remained normoglycemic postoperatively, while 54% became mildly hyperglycemic and 11% severely hyperglycemic.

Postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic patients was associated with greater intraoperative estimated blood loss. The transfusion rate was 4.8% in normoglycemic patients, 10.3% in mildly hyperglycemic ones, and 18.1% in those with severe hyperglycemia. The length of surgery averaged 137 minutes in normoglycemic patients, 166 minutes in patients with postoperative mild hyperglycemia, and 181 minutes in patients with severe hyperglycemia.

Any episode of postoperative severe hyperglycemia in the nondiabetic patients was associated with significantly higher rates of both superficial and deep surgical site infections, greater length of stay, and higher 30-day mortality, compared with normoglycemic patients (see chart). Mild hyperglycemia wasn’t associated with as many complications; however, it was linked to a significantly increased rate of sepsis and a greater length of stay.

Moreover, in a multivariate analysis mild hyperglycemia was independently associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of reoperation within 30 days, while severe hyperglycemia carried a 3.8-fold increased risk, compared with normoglycemia, continued Dr. Kiran of the Cleveland Clinic.

The investigators identified two major independent risk factors for sepsis in nondiabetic patients: an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status class of 3 or more (odds ratio, 4.2), and postoperative hyperglycemia, which was associated with roughly an 8-fold risk regardless of whether the hyperglycemia was mild or severe.

Studies from the cardiovascular and trauma surgery literature suggest postoperative uncontrolled blood glucose may lead to adverse outcomes. Dr. Kiran and his coworkers performed this study because the impact of elevated blood glucose after elective major abdominal surgery had not been well defined, although colorectal surgery entails bacterial contamination, so background rates of surgical site and other infectious complications already tend to run relatively high.

Dr. Kiran said he believes postoperative hyperglycemia is probably a surrogate marker, perhaps for a distressed physiologic state or for looming complications. The next major question he and his coinvestigators want to tackle is this: Do prompt recognition and management of postoperative hyperglycemia in nondiabetic colorectal resection patients improve outcomes?

A cautionary note was sounded by discussant Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.,who emphasized that management strategies involving tight glucose control entail the risk of potentially disastrous postsurgical hypoglycemia.

"As many of you know, there are more than half a dozen patients in the midwestern U.S. who’ve been rendered badly hurt with hypoglycemia and cerebral damage. They’re working their way through the legal system at this point. It’s a fine balance: Sometimes perfection is the enemy of good in this situation," warned Dr. Polk, professor and chairman of the surgery department at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

He noted as an aside that just as Dr. Kiran found that even a single episode of postoperative hyperglycemia has adverse consequences, he and his Louisville coworkers have found the same is true for hypothermia.

"A single brief episode of hypothermia seems to throw the wheels off the track. It disrupts something in host defenses and makes everything very difficult," Dr. Polk observed.

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Mild hyperglycemia occurring within 48 hours after major colorectal surgery in nondiabetic patients was independently associated with a doubled risk of reoperation within 30 days and a 7.9-fold increase in sepsis, compared with patients who remained normoglycemic. Severe hyperglycemia – a blood glucose measurement in excess of 200 mg/dL – was associated with even worse outcomes.

Data source: A single-center study of more than 16,000 postoperative blood glucose measurements in 2,628 consecutive patients who underwent colorectal resection.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Dr. Kiran reported no financial conflicts.