User login

American Surgical Association (ASA): Annual Meeting

Better endografts mean fewer reinterventions for endovascular AAA

INDIANAPOLIS – Reintervention rates following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms have fallen steadily with the introduction of each successive generation of endografts, while reintervention rates after open surgical repair remained stable during a recent 15-year period.

This was among the key findings from the first in-depth analysis of reinterventions occurring in contemporaneous cohorts of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open repair. The large single-center retrospective study demonstrated major differences between the two treatment strategies in terms of the incidence, nature, timing, and mortality associated with complications requiring reintervention, Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Dr. Al-Jubouri of Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, reported on the 1,144 patients who underwent AAA repair there during 1996-2011. Forty-nine percent had EVAR, 51% open surgical repair. Beginning in 2003, more EVARs than open repairs were done annually at the Toledo institute, consistent with the experience at many major centers in the United States and elsewhere, where EVAR has become the first-line treatment based upon evidence that it offers lower operative mortality, less blood loss, and shorter ICU and hospital lengths of stay.

These advantages come at a cost, however: namely, a greater rate of secondary interventions, mainly due to device migration, failure, or endoleaks. The purpose of Dr. Al-Jubouri’s study was to evaluate the rates and reasons for reintervention over time in the two cohorts, as well as the impact of reintervention on long-term survival.

Reintervention was required in 13.6% of the EVAR group during a mean follow-up of 4.58 years, and in 5.1% of the open surgery group during 6.58 years. A single reintervention occurred in 7.9% of EVAR patients and 3.6% of the open repair group. More than one reintervention was required in 5.8% of EVAR patients compared to just 1.6% of the open repair group.

The types and timing of complications leading to reintervention were very different in the two groups. Sixty-eight percent of reinterventions in the EVAR group were for treatment of endoleaks. Another 11.5% were to address device migration, and an equal number were for occlusion.

In contrast, the three most frequent causes of reintervention in the open repair group were colonic ischemia, accounting for 30.4% of reintervention procedures; severe bleeding, 21.7%; and incisional hernia, which triggered another 21.7% of reinterventions.

Notably, 60% of all reinterventions in the open repair group occurred during the initial hospitalization, while less than 7% of reinterventions in the EVAR patients happened within 1 month of the index procedure and only one-third within the first year, the surgeon continued.

Thirty-day mortality in EVAR patients who underwent reintervention within the first month was zero, compared to a 23.3% mortality rate in open repair patients requiring reintervention within 1 month. However, when patients did not require early reintervention, 30-day mortality rates in the two groups did not differ significantly: 1.9% in EVAR group and in the open repair group. That means when patients in the open surgery group required early reintervention, their mortality rate shot up sevenfold.

After the first 30 days post-index procedure, long-term survival rates in the two groups were similar.

Need for reintervention in the open repair group was strongly related to larger aneurysm size. In contrast, reintervention rates were similar in the EVAR group regardless of aneurysm size.

A first reintervention after EVAR occurred in 23.7% of patients who received a first-generation endograft, such as the Ancure or Talent; in 16.2% of those who got the second-generation AneuRx endograft; and in 9.1% with a third-generation endograft, such as the Excluder, Endurant, Powerlink, or Zenith. The annualized rate of reintervention during the first 3 years of follow-up was 6.8% per year with first-generation devices, 7.2% per year with second-generation endografts, and significantly lower at 3.4% per year with the third-generation.

One major reason reintervention rates in EVAR patients have declined over time is that each newer generation of endograft is lower-profile, easier to deploy, and more durable. Also, many of the surgeons now putting in third-generation endografts were performing EVAR 15 years ago; they’re very experienced operators, Dr. Al-Jubouri noted.

Discussant Dr. James R. Debord proposed another explanation for the decrease in EVAR reinterventions over time.

"Isn’t it much more likely that it’s due to recognition of the fact that many of these type 2 endoleaks that we used to intervene on early on don’t require reintervention unless there’s sac enlargement?" commented Dr. Debord, professor of clinical surgery and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Illinois at Peoria.

Dr. Al-Jubouri concurred that this is an important factor in the declining rate of EVAR reinterventions.

"We saw a significant decrease in reinterventions for type 2 endoleaks between the first, second, and third generations," he said.

Asked how his study findings have changed the follow-up protocols at Jobst Vascular Institute, the surgeon replied that in the early years of the series EVAR patients got a CT scan at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. This evaluation has evolved over time. Now EVAR patients get a CT scan at 6-12 weeks, and duplex ultrasounds at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter.

"There is no standardized follow-up for open repair patients. However, most [patients] get an annual duplex ultrasound for their follow-up. A CT scan is not part of the follow-up of patients with open repair. But most if not all of the complications that developed in the open repair group were symptomatic," he explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri and his colleagues assessed reinterventions and outcomes after EVAR and open AAA repair over a long time period, and found decreasing rates of reintervention after EVAR, which they attribute to improvements in technology from first to third and later-generation devices. I would concur with the one discussant, that some of the decrease may also be due to the understanding that not all type II endoleaks require repair. Further, much of the decrease may be due to physician experience – both with appropriate patient and device selection, and technical expertise, including with deployment. However, regardless of the underlying reason for the improvement in the reintervention rate, it is heartening that reintervention is decreasing as physicians become more facile, and industry provides technological improvements to the devices.

Dr. Linda Harris, FACS, is division chief and program director of vascular surgery at State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris has no disclosures

Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri and his colleagues assessed reinterventions and outcomes after EVAR and open AAA repair over a long time period, and found decreasing rates of reintervention after EVAR, which they attribute to improvements in technology from first to third and later-generation devices. I would concur with the one discussant, that some of the decrease may also be due to the understanding that not all type II endoleaks require repair. Further, much of the decrease may be due to physician experience – both with appropriate patient and device selection, and technical expertise, including with deployment. However, regardless of the underlying reason for the improvement in the reintervention rate, it is heartening that reintervention is decreasing as physicians become more facile, and industry provides technological improvements to the devices.

Dr. Linda Harris, FACS, is division chief and program director of vascular surgery at State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris has no disclosures

Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri and his colleagues assessed reinterventions and outcomes after EVAR and open AAA repair over a long time period, and found decreasing rates of reintervention after EVAR, which they attribute to improvements in technology from first to third and later-generation devices. I would concur with the one discussant, that some of the decrease may also be due to the understanding that not all type II endoleaks require repair. Further, much of the decrease may be due to physician experience – both with appropriate patient and device selection, and technical expertise, including with deployment. However, regardless of the underlying reason for the improvement in the reintervention rate, it is heartening that reintervention is decreasing as physicians become more facile, and industry provides technological improvements to the devices.

Dr. Linda Harris, FACS, is division chief and program director of vascular surgery at State University of New York, Buffalo. Dr. Harris has no disclosures

INDIANAPOLIS – Reintervention rates following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms have fallen steadily with the introduction of each successive generation of endografts, while reintervention rates after open surgical repair remained stable during a recent 15-year period.

This was among the key findings from the first in-depth analysis of reinterventions occurring in contemporaneous cohorts of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open repair. The large single-center retrospective study demonstrated major differences between the two treatment strategies in terms of the incidence, nature, timing, and mortality associated with complications requiring reintervention, Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Dr. Al-Jubouri of Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, reported on the 1,144 patients who underwent AAA repair there during 1996-2011. Forty-nine percent had EVAR, 51% open surgical repair. Beginning in 2003, more EVARs than open repairs were done annually at the Toledo institute, consistent with the experience at many major centers in the United States and elsewhere, where EVAR has become the first-line treatment based upon evidence that it offers lower operative mortality, less blood loss, and shorter ICU and hospital lengths of stay.

These advantages come at a cost, however: namely, a greater rate of secondary interventions, mainly due to device migration, failure, or endoleaks. The purpose of Dr. Al-Jubouri’s study was to evaluate the rates and reasons for reintervention over time in the two cohorts, as well as the impact of reintervention on long-term survival.

Reintervention was required in 13.6% of the EVAR group during a mean follow-up of 4.58 years, and in 5.1% of the open surgery group during 6.58 years. A single reintervention occurred in 7.9% of EVAR patients and 3.6% of the open repair group. More than one reintervention was required in 5.8% of EVAR patients compared to just 1.6% of the open repair group.

The types and timing of complications leading to reintervention were very different in the two groups. Sixty-eight percent of reinterventions in the EVAR group were for treatment of endoleaks. Another 11.5% were to address device migration, and an equal number were for occlusion.

In contrast, the three most frequent causes of reintervention in the open repair group were colonic ischemia, accounting for 30.4% of reintervention procedures; severe bleeding, 21.7%; and incisional hernia, which triggered another 21.7% of reinterventions.

Notably, 60% of all reinterventions in the open repair group occurred during the initial hospitalization, while less than 7% of reinterventions in the EVAR patients happened within 1 month of the index procedure and only one-third within the first year, the surgeon continued.

Thirty-day mortality in EVAR patients who underwent reintervention within the first month was zero, compared to a 23.3% mortality rate in open repair patients requiring reintervention within 1 month. However, when patients did not require early reintervention, 30-day mortality rates in the two groups did not differ significantly: 1.9% in EVAR group and in the open repair group. That means when patients in the open surgery group required early reintervention, their mortality rate shot up sevenfold.

After the first 30 days post-index procedure, long-term survival rates in the two groups were similar.

Need for reintervention in the open repair group was strongly related to larger aneurysm size. In contrast, reintervention rates were similar in the EVAR group regardless of aneurysm size.

A first reintervention after EVAR occurred in 23.7% of patients who received a first-generation endograft, such as the Ancure or Talent; in 16.2% of those who got the second-generation AneuRx endograft; and in 9.1% with a third-generation endograft, such as the Excluder, Endurant, Powerlink, or Zenith. The annualized rate of reintervention during the first 3 years of follow-up was 6.8% per year with first-generation devices, 7.2% per year with second-generation endografts, and significantly lower at 3.4% per year with the third-generation.

One major reason reintervention rates in EVAR patients have declined over time is that each newer generation of endograft is lower-profile, easier to deploy, and more durable. Also, many of the surgeons now putting in third-generation endografts were performing EVAR 15 years ago; they’re very experienced operators, Dr. Al-Jubouri noted.

Discussant Dr. James R. Debord proposed another explanation for the decrease in EVAR reinterventions over time.

"Isn’t it much more likely that it’s due to recognition of the fact that many of these type 2 endoleaks that we used to intervene on early on don’t require reintervention unless there’s sac enlargement?" commented Dr. Debord, professor of clinical surgery and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Illinois at Peoria.

Dr. Al-Jubouri concurred that this is an important factor in the declining rate of EVAR reinterventions.

"We saw a significant decrease in reinterventions for type 2 endoleaks between the first, second, and third generations," he said.

Asked how his study findings have changed the follow-up protocols at Jobst Vascular Institute, the surgeon replied that in the early years of the series EVAR patients got a CT scan at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. This evaluation has evolved over time. Now EVAR patients get a CT scan at 6-12 weeks, and duplex ultrasounds at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter.

"There is no standardized follow-up for open repair patients. However, most [patients] get an annual duplex ultrasound for their follow-up. A CT scan is not part of the follow-up of patients with open repair. But most if not all of the complications that developed in the open repair group were symptomatic," he explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Reintervention rates following endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms have fallen steadily with the introduction of each successive generation of endografts, while reintervention rates after open surgical repair remained stable during a recent 15-year period.

This was among the key findings from the first in-depth analysis of reinterventions occurring in contemporaneous cohorts of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or open repair. The large single-center retrospective study demonstrated major differences between the two treatment strategies in terms of the incidence, nature, timing, and mortality associated with complications requiring reintervention, Dr. Mustafa Al-Jubouri said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Dr. Al-Jubouri of Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, reported on the 1,144 patients who underwent AAA repair there during 1996-2011. Forty-nine percent had EVAR, 51% open surgical repair. Beginning in 2003, more EVARs than open repairs were done annually at the Toledo institute, consistent with the experience at many major centers in the United States and elsewhere, where EVAR has become the first-line treatment based upon evidence that it offers lower operative mortality, less blood loss, and shorter ICU and hospital lengths of stay.

These advantages come at a cost, however: namely, a greater rate of secondary interventions, mainly due to device migration, failure, or endoleaks. The purpose of Dr. Al-Jubouri’s study was to evaluate the rates and reasons for reintervention over time in the two cohorts, as well as the impact of reintervention on long-term survival.

Reintervention was required in 13.6% of the EVAR group during a mean follow-up of 4.58 years, and in 5.1% of the open surgery group during 6.58 years. A single reintervention occurred in 7.9% of EVAR patients and 3.6% of the open repair group. More than one reintervention was required in 5.8% of EVAR patients compared to just 1.6% of the open repair group.

The types and timing of complications leading to reintervention were very different in the two groups. Sixty-eight percent of reinterventions in the EVAR group were for treatment of endoleaks. Another 11.5% were to address device migration, and an equal number were for occlusion.

In contrast, the three most frequent causes of reintervention in the open repair group were colonic ischemia, accounting for 30.4% of reintervention procedures; severe bleeding, 21.7%; and incisional hernia, which triggered another 21.7% of reinterventions.

Notably, 60% of all reinterventions in the open repair group occurred during the initial hospitalization, while less than 7% of reinterventions in the EVAR patients happened within 1 month of the index procedure and only one-third within the first year, the surgeon continued.

Thirty-day mortality in EVAR patients who underwent reintervention within the first month was zero, compared to a 23.3% mortality rate in open repair patients requiring reintervention within 1 month. However, when patients did not require early reintervention, 30-day mortality rates in the two groups did not differ significantly: 1.9% in EVAR group and in the open repair group. That means when patients in the open surgery group required early reintervention, their mortality rate shot up sevenfold.

After the first 30 days post-index procedure, long-term survival rates in the two groups were similar.

Need for reintervention in the open repair group was strongly related to larger aneurysm size. In contrast, reintervention rates were similar in the EVAR group regardless of aneurysm size.

A first reintervention after EVAR occurred in 23.7% of patients who received a first-generation endograft, such as the Ancure or Talent; in 16.2% of those who got the second-generation AneuRx endograft; and in 9.1% with a third-generation endograft, such as the Excluder, Endurant, Powerlink, or Zenith. The annualized rate of reintervention during the first 3 years of follow-up was 6.8% per year with first-generation devices, 7.2% per year with second-generation endografts, and significantly lower at 3.4% per year with the third-generation.

One major reason reintervention rates in EVAR patients have declined over time is that each newer generation of endograft is lower-profile, easier to deploy, and more durable. Also, many of the surgeons now putting in third-generation endografts were performing EVAR 15 years ago; they’re very experienced operators, Dr. Al-Jubouri noted.

Discussant Dr. James R. Debord proposed another explanation for the decrease in EVAR reinterventions over time.

"Isn’t it much more likely that it’s due to recognition of the fact that many of these type 2 endoleaks that we used to intervene on early on don’t require reintervention unless there’s sac enlargement?" commented Dr. Debord, professor of clinical surgery and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Illinois at Peoria.

Dr. Al-Jubouri concurred that this is an important factor in the declining rate of EVAR reinterventions.

"We saw a significant decrease in reinterventions for type 2 endoleaks between the first, second, and third generations," he said.

Asked how his study findings have changed the follow-up protocols at Jobst Vascular Institute, the surgeon replied that in the early years of the series EVAR patients got a CT scan at 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter. This evaluation has evolved over time. Now EVAR patients get a CT scan at 6-12 weeks, and duplex ultrasounds at 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter.

"There is no standardized follow-up for open repair patients. However, most [patients] get an annual duplex ultrasound for their follow-up. A CT scan is not part of the follow-up of patients with open repair. But most if not all of the complications that developed in the open repair group were symptomatic," he explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: Reintervention rates were markedly higher following endovascular repair compared with open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms, but the adverse effects associated with reintervention after open repair were far more serious.

Data Source: A retrospective study of the 15-year experience at a large-volume vascular surgery. It encompassed 1,144 patients who underwent abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and their subsequent reintervention rates.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no conflicts of interest.

Robotic pancreatic resection safe in 250-patient series

INDIANAPOLIS – Robotic-assisted major pancreatic resection is safe, feasible, reliable, and versatile, according to the findings of the largest reported single-center series of such procedures.

That being said, the next and absolutely critical step needs to be comparative effectiveness studies pitting robotic versus laparoscopic or open pancreatic resections, Dr. Herbert J. Zeh III reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He noted that there was a considerable learning curve with the procedure in this single-center series of 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections. "If we had compared our first 30, 40, or even 60 cases, we would have been comparing an innovative procedure to one that’s been refined continuously since 1937," noted Dr. Zeh of the University of Pittsburgh.

Discussants praised Dr. Zeh and his coinvestigators as innovators who are taking a rigorously scientific and cautious approach in investigating the applicability of robotic techniques to major pancreatic surgery. But some discussants were concerned that the growing dissemination of robotic surgery is based largely upon what they consider to be marketing hype and competitive pressure.

Dr. Zeh explained that he and his coworkers have undertaken the study of robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections because they believe that a minimally invasive approach will reduce the substantial morbidity traditionally associated with open procedures, and that laparoscopic techniques aren’t the answer in these complex resections, which often require resuturing the pancreas to the GI tract.

"It was our perception as a group of dedicated pancreatic surgeons that we could not utilize the laparoscopic technology to adhere to the standard principles of open surgery that we thought were important for safe performance of pancreatic resections. These include meticulous dissection, safe control of major vascular structures, and precise suturing," he said.

The 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections in this series included the full range of complex pancreatic operations. The two most common procedures were pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as the Whipple procedure, in 132 patients and distal pancreatectomy in 83.

Overall 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0.8% and 2.0%, respectively. All deaths were in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients, with 30- and 90-day mortality rates of 1.5% and 3.8%.

Clinically significant complications occurred in 21% of patients. The most common was intra-abdominal fluid collection requiring drainage via interventional radiology. Morbidity rates were similar to those reported in large series of open and laparoscopic pancreatic resections.

Estimated blood loss in pancreaticoduodenectomy averaged 499 mL in the first one-third of patients who had the robotic procedure; thereafter, the blood loss improved to 401 mL.

Rates of conversion from robotic to open surgery also improved over time, from 18.2% in the first third of the patient series to 3.4% in the latter two-thirds.

Mean operative time was 529 minutes for pancreaticoduodenectomy and 256 minutes for distal pancreatectomy. These times have dropped steadily with experience such that mean operative time in the last 50 pancreaticoduodenectomies was 444 minutes, while in the last 50 distal pancreatectomies it was 222 minutes, which approaches reported times for laparoscopic and open operations, Dr. Zeh noted.

The median length of stay was 10 days for pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 6 days for those undergoing distal pancreatectomy. As a precautionary measure, surgeons kept patients treated early in the series in the hospital longer than was probably necessary. Length of stay has come down over time, although this trend hasn’t yet reached statistical significance.

The readmission rate was 24% in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 28% in distal pancreatectomy patients; 2% of patients required a reoperation.

As experience has grown, the group’s criteria for selecting patients for the robotic approach have loosened considerably. Many recent patients have been obese or superobese.

"Currently the only absolute contraindication is some sort of vascular involvement that would entail resecting a vein and reanastomosing it using a minimally invasive approach. That’s really the only frontier we haven’t crossed," said Dr. Zeh.

The potential advantages of the robotic platform that drew the researchers’ interest include greater range of motion for the robotic needle driver and other tools, compared with what is achievable laparoscopically; enhanced visualization with magnification; computerized smoothing of a surgeon’s tremor; and the ability to see structures in three dimensions, unlike in laparoscopy.

"I think the real advantage is the computer," he added. "Robotic surgery is probably misnamed; it’s really computer-assisted surgery. What this is going to allow us to do is to take the skill sets that we have to the next level. Pilots couldn’t control fighter jets without a computer between them and the plane. In the end, I think the addition of the computer between us and the patient is going to allow us to do things that we haven’t even thought about."

He reported having received an honorarium from Medtronic on a single occasion for participation in a symposium on minimally invasive pancreatic surgery.

When it comes to robotic surgery, the emperor is not wearing any clothes. I don’t believe there has ever been a series that has conclusively shown that the robot has made any difference in patient outcomes or quality of the procedure. I believe that it is a technology that enables surgeons who cannot otherwise perform the procedure to perform the procedure. That’s been shown in the urology literature, particularly.

What’s going on in my community and others throughout the country is a terrible abuse of this technology, where we have doctors in our local hospitals taking out ovaries with this technology, taking out a uterus, and who are doing single-site robotic cholecystectomies in 4 hours at $4,000 in cost. They’re using robotic technology to do simple procedures that could otherwise be done better and faster without this technology.

We need to be outspoken and realistic about the use of robotic surgery. We need to advance this technology, but carefully and with a caveat.

Dr. Jeffrey L. Ponsky is professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. He made his remarks as a discussant at the meeting.

When it comes to robotic surgery, the emperor is not wearing any clothes. I don’t believe there has ever been a series that has conclusively shown that the robot has made any difference in patient outcomes or quality of the procedure. I believe that it is a technology that enables surgeons who cannot otherwise perform the procedure to perform the procedure. That’s been shown in the urology literature, particularly.

What’s going on in my community and others throughout the country is a terrible abuse of this technology, where we have doctors in our local hospitals taking out ovaries with this technology, taking out a uterus, and who are doing single-site robotic cholecystectomies in 4 hours at $4,000 in cost. They’re using robotic technology to do simple procedures that could otherwise be done better and faster without this technology.

We need to be outspoken and realistic about the use of robotic surgery. We need to advance this technology, but carefully and with a caveat.

Dr. Jeffrey L. Ponsky is professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. He made his remarks as a discussant at the meeting.

When it comes to robotic surgery, the emperor is not wearing any clothes. I don’t believe there has ever been a series that has conclusively shown that the robot has made any difference in patient outcomes or quality of the procedure. I believe that it is a technology that enables surgeons who cannot otherwise perform the procedure to perform the procedure. That’s been shown in the urology literature, particularly.

What’s going on in my community and others throughout the country is a terrible abuse of this technology, where we have doctors in our local hospitals taking out ovaries with this technology, taking out a uterus, and who are doing single-site robotic cholecystectomies in 4 hours at $4,000 in cost. They’re using robotic technology to do simple procedures that could otherwise be done better and faster without this technology.

We need to be outspoken and realistic about the use of robotic surgery. We need to advance this technology, but carefully and with a caveat.

Dr. Jeffrey L. Ponsky is professor and chairman of the department of surgery at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. He made his remarks as a discussant at the meeting.

INDIANAPOLIS – Robotic-assisted major pancreatic resection is safe, feasible, reliable, and versatile, according to the findings of the largest reported single-center series of such procedures.

That being said, the next and absolutely critical step needs to be comparative effectiveness studies pitting robotic versus laparoscopic or open pancreatic resections, Dr. Herbert J. Zeh III reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He noted that there was a considerable learning curve with the procedure in this single-center series of 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections. "If we had compared our first 30, 40, or even 60 cases, we would have been comparing an innovative procedure to one that’s been refined continuously since 1937," noted Dr. Zeh of the University of Pittsburgh.

Discussants praised Dr. Zeh and his coinvestigators as innovators who are taking a rigorously scientific and cautious approach in investigating the applicability of robotic techniques to major pancreatic surgery. But some discussants were concerned that the growing dissemination of robotic surgery is based largely upon what they consider to be marketing hype and competitive pressure.

Dr. Zeh explained that he and his coworkers have undertaken the study of robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections because they believe that a minimally invasive approach will reduce the substantial morbidity traditionally associated with open procedures, and that laparoscopic techniques aren’t the answer in these complex resections, which often require resuturing the pancreas to the GI tract.

"It was our perception as a group of dedicated pancreatic surgeons that we could not utilize the laparoscopic technology to adhere to the standard principles of open surgery that we thought were important for safe performance of pancreatic resections. These include meticulous dissection, safe control of major vascular structures, and precise suturing," he said.

The 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections in this series included the full range of complex pancreatic operations. The two most common procedures were pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as the Whipple procedure, in 132 patients and distal pancreatectomy in 83.

Overall 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0.8% and 2.0%, respectively. All deaths were in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients, with 30- and 90-day mortality rates of 1.5% and 3.8%.

Clinically significant complications occurred in 21% of patients. The most common was intra-abdominal fluid collection requiring drainage via interventional radiology. Morbidity rates were similar to those reported in large series of open and laparoscopic pancreatic resections.

Estimated blood loss in pancreaticoduodenectomy averaged 499 mL in the first one-third of patients who had the robotic procedure; thereafter, the blood loss improved to 401 mL.

Rates of conversion from robotic to open surgery also improved over time, from 18.2% in the first third of the patient series to 3.4% in the latter two-thirds.

Mean operative time was 529 minutes for pancreaticoduodenectomy and 256 minutes for distal pancreatectomy. These times have dropped steadily with experience such that mean operative time in the last 50 pancreaticoduodenectomies was 444 minutes, while in the last 50 distal pancreatectomies it was 222 minutes, which approaches reported times for laparoscopic and open operations, Dr. Zeh noted.

The median length of stay was 10 days for pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 6 days for those undergoing distal pancreatectomy. As a precautionary measure, surgeons kept patients treated early in the series in the hospital longer than was probably necessary. Length of stay has come down over time, although this trend hasn’t yet reached statistical significance.

The readmission rate was 24% in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 28% in distal pancreatectomy patients; 2% of patients required a reoperation.

As experience has grown, the group’s criteria for selecting patients for the robotic approach have loosened considerably. Many recent patients have been obese or superobese.

"Currently the only absolute contraindication is some sort of vascular involvement that would entail resecting a vein and reanastomosing it using a minimally invasive approach. That’s really the only frontier we haven’t crossed," said Dr. Zeh.

The potential advantages of the robotic platform that drew the researchers’ interest include greater range of motion for the robotic needle driver and other tools, compared with what is achievable laparoscopically; enhanced visualization with magnification; computerized smoothing of a surgeon’s tremor; and the ability to see structures in three dimensions, unlike in laparoscopy.

"I think the real advantage is the computer," he added. "Robotic surgery is probably misnamed; it’s really computer-assisted surgery. What this is going to allow us to do is to take the skill sets that we have to the next level. Pilots couldn’t control fighter jets without a computer between them and the plane. In the end, I think the addition of the computer between us and the patient is going to allow us to do things that we haven’t even thought about."

He reported having received an honorarium from Medtronic on a single occasion for participation in a symposium on minimally invasive pancreatic surgery.

INDIANAPOLIS – Robotic-assisted major pancreatic resection is safe, feasible, reliable, and versatile, according to the findings of the largest reported single-center series of such procedures.

That being said, the next and absolutely critical step needs to be comparative effectiveness studies pitting robotic versus laparoscopic or open pancreatic resections, Dr. Herbert J. Zeh III reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

He noted that there was a considerable learning curve with the procedure in this single-center series of 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections. "If we had compared our first 30, 40, or even 60 cases, we would have been comparing an innovative procedure to one that’s been refined continuously since 1937," noted Dr. Zeh of the University of Pittsburgh.

Discussants praised Dr. Zeh and his coinvestigators as innovators who are taking a rigorously scientific and cautious approach in investigating the applicability of robotic techniques to major pancreatic surgery. But some discussants were concerned that the growing dissemination of robotic surgery is based largely upon what they consider to be marketing hype and competitive pressure.

Dr. Zeh explained that he and his coworkers have undertaken the study of robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections because they believe that a minimally invasive approach will reduce the substantial morbidity traditionally associated with open procedures, and that laparoscopic techniques aren’t the answer in these complex resections, which often require resuturing the pancreas to the GI tract.

"It was our perception as a group of dedicated pancreatic surgeons that we could not utilize the laparoscopic technology to adhere to the standard principles of open surgery that we thought were important for safe performance of pancreatic resections. These include meticulous dissection, safe control of major vascular structures, and precise suturing," he said.

The 250 consecutive robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections in this series included the full range of complex pancreatic operations. The two most common procedures were pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as the Whipple procedure, in 132 patients and distal pancreatectomy in 83.

Overall 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0.8% and 2.0%, respectively. All deaths were in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients, with 30- and 90-day mortality rates of 1.5% and 3.8%.

Clinically significant complications occurred in 21% of patients. The most common was intra-abdominal fluid collection requiring drainage via interventional radiology. Morbidity rates were similar to those reported in large series of open and laparoscopic pancreatic resections.

Estimated blood loss in pancreaticoduodenectomy averaged 499 mL in the first one-third of patients who had the robotic procedure; thereafter, the blood loss improved to 401 mL.

Rates of conversion from robotic to open surgery also improved over time, from 18.2% in the first third of the patient series to 3.4% in the latter two-thirds.

Mean operative time was 529 minutes for pancreaticoduodenectomy and 256 minutes for distal pancreatectomy. These times have dropped steadily with experience such that mean operative time in the last 50 pancreaticoduodenectomies was 444 minutes, while in the last 50 distal pancreatectomies it was 222 minutes, which approaches reported times for laparoscopic and open operations, Dr. Zeh noted.

The median length of stay was 10 days for pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 6 days for those undergoing distal pancreatectomy. As a precautionary measure, surgeons kept patients treated early in the series in the hospital longer than was probably necessary. Length of stay has come down over time, although this trend hasn’t yet reached statistical significance.

The readmission rate was 24% in pancreaticoduodenectomy patients and 28% in distal pancreatectomy patients; 2% of patients required a reoperation.

As experience has grown, the group’s criteria for selecting patients for the robotic approach have loosened considerably. Many recent patients have been obese or superobese.

"Currently the only absolute contraindication is some sort of vascular involvement that would entail resecting a vein and reanastomosing it using a minimally invasive approach. That’s really the only frontier we haven’t crossed," said Dr. Zeh.

The potential advantages of the robotic platform that drew the researchers’ interest include greater range of motion for the robotic needle driver and other tools, compared with what is achievable laparoscopically; enhanced visualization with magnification; computerized smoothing of a surgeon’s tremor; and the ability to see structures in three dimensions, unlike in laparoscopy.

"I think the real advantage is the computer," he added. "Robotic surgery is probably misnamed; it’s really computer-assisted surgery. What this is going to allow us to do is to take the skill sets that we have to the next level. Pilots couldn’t control fighter jets without a computer between them and the plane. In the end, I think the addition of the computer between us and the patient is going to allow us to do things that we haven’t even thought about."

He reported having received an honorarium from Medtronic on a single occasion for participation in a symposium on minimally invasive pancreatic surgery.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Overall 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0.8% and 2.0%, respectively, following various types of robotic-assisted major pancreatic resection, with deaths occurring only in the subset of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Data source: A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained single-center database of 250 consecutive patients undergoing robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having received an honorarium from Medtronic on a single occasion.

Endovascular AAA repair superior for kidney disease patients

INDIANAPOLIS – Contrary to conventional wisdom, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) provides outcomes superior to those achieved with open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, a large study indicates.

"EVAR should be the first-line therapy in the patient with chronic renal insufficiency when the patient has the appropriate anatomy. However, in patients with severe renal impairment, a higher threshold should be applied for repair because the risks of both open repair and EVAR are significantly higher," Dr. Bao-Ngoc H. Nguyen declared at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

"Chronic renal failure is quite prevalent in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm: up to 30%. It is quite worrisome because any further decline in renal function in these patients could push them toward dialysis. More than that, postoperative renal failure is a predictor for early and late mortality," noted Dr. Nguyen of George Washington University, Washington.

She presented a retrospective study in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm and chronic kidney disease. The aim, she explained, was to answer a key question: "Which one of these two treatment modalities is the lesser of two evils?"

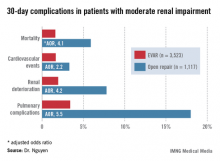

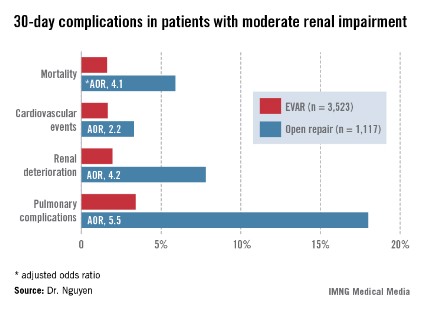

For answers, Dr. Nguyen and coinvestigators turned to the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for 2005-2010. They identified 3,523 patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-60 mL/minute, who underwent EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm and 1,117 treated via open surgical repair. Another 363 EVAR patients had severe chronic renal insufficiency, with an eGFR of less than 30 mL/minute, as did 139 patients who underwent open repair. Vascular surgeons performed all procedures in this study.

Patients with moderate renal insufficiency who underwent EVAR had markedly lower 30-day rates of mortality, pulmonary complications, cardiovascular events, and postoperative renal dysfunction, including acute kidney injury, than did those who had open surgical repair. One or more adverse events occurred in 6% of the EVAR group, compared with 24.1% of open repair patients. In a multivariate analysis controlled for preoperative differences in the patient groups, those undergoing open repair had an adjusted 4.1-fold greater risk of mortality as well as a 2.2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events, a 4.2-fold increased risk of renal deterioration including a 5.2-fold greater risk of dialysis, and additional hazards.

In contrast, among the much smaller population of patients with baseline severe chronic renal insufficiency, there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups in terms of 30-day mortality, postoperative renal deterioration, or cardiovascular complications, although pulmonary complications were an adjusted fivefold more likely in the open surgery than among EVAR patients. Of note, rates of all adverse outcomes were markedly higher in both groups than in those with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, such that one or more adverse events occurred in 16.9% of EVAR patients and 42.5% of the open repair patients with severe chronic renal insufficiency.

Discussant Dr. Michael Watkins commented that this study has one glaring shortcoming resulting from a limitation of the NSQIP database.

While NSQIP contains only validated data entered by unbiased, well-trained professionals and NSQIP is "far superior" to the various administrative databases commonly used in evaluating outcomes, it doesn’t include key details about patients’ presenting anatomy, observed Dr. Watkins, director of the vascular research laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

"Was the anatomy really similar in the two groups, or were patients who underwent open repair not candidates for EVAR?" he asked.

Dr. Nguyen conceded that this constitutes a major study limitation, adding that she agrees with Dr. Watkins that anatomy should be the first and foremost factor considered in deciding upon the surgical approach in abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Contrary to conventional wisdom, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) provides outcomes superior to those achieved with open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, a large study indicates.

"EVAR should be the first-line therapy in the patient with chronic renal insufficiency when the patient has the appropriate anatomy. However, in patients with severe renal impairment, a higher threshold should be applied for repair because the risks of both open repair and EVAR are significantly higher," Dr. Bao-Ngoc H. Nguyen declared at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

"Chronic renal failure is quite prevalent in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm: up to 30%. It is quite worrisome because any further decline in renal function in these patients could push them toward dialysis. More than that, postoperative renal failure is a predictor for early and late mortality," noted Dr. Nguyen of George Washington University, Washington.

She presented a retrospective study in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm and chronic kidney disease. The aim, she explained, was to answer a key question: "Which one of these two treatment modalities is the lesser of two evils?"

For answers, Dr. Nguyen and coinvestigators turned to the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for 2005-2010. They identified 3,523 patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-60 mL/minute, who underwent EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm and 1,117 treated via open surgical repair. Another 363 EVAR patients had severe chronic renal insufficiency, with an eGFR of less than 30 mL/minute, as did 139 patients who underwent open repair. Vascular surgeons performed all procedures in this study.

Patients with moderate renal insufficiency who underwent EVAR had markedly lower 30-day rates of mortality, pulmonary complications, cardiovascular events, and postoperative renal dysfunction, including acute kidney injury, than did those who had open surgical repair. One or more adverse events occurred in 6% of the EVAR group, compared with 24.1% of open repair patients. In a multivariate analysis controlled for preoperative differences in the patient groups, those undergoing open repair had an adjusted 4.1-fold greater risk of mortality as well as a 2.2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events, a 4.2-fold increased risk of renal deterioration including a 5.2-fold greater risk of dialysis, and additional hazards.

In contrast, among the much smaller population of patients with baseline severe chronic renal insufficiency, there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups in terms of 30-day mortality, postoperative renal deterioration, or cardiovascular complications, although pulmonary complications were an adjusted fivefold more likely in the open surgery than among EVAR patients. Of note, rates of all adverse outcomes were markedly higher in both groups than in those with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, such that one or more adverse events occurred in 16.9% of EVAR patients and 42.5% of the open repair patients with severe chronic renal insufficiency.

Discussant Dr. Michael Watkins commented that this study has one glaring shortcoming resulting from a limitation of the NSQIP database.

While NSQIP contains only validated data entered by unbiased, well-trained professionals and NSQIP is "far superior" to the various administrative databases commonly used in evaluating outcomes, it doesn’t include key details about patients’ presenting anatomy, observed Dr. Watkins, director of the vascular research laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

"Was the anatomy really similar in the two groups, or were patients who underwent open repair not candidates for EVAR?" he asked.

Dr. Nguyen conceded that this constitutes a major study limitation, adding that she agrees with Dr. Watkins that anatomy should be the first and foremost factor considered in deciding upon the surgical approach in abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – Contrary to conventional wisdom, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) provides outcomes superior to those achieved with open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, a large study indicates.

"EVAR should be the first-line therapy in the patient with chronic renal insufficiency when the patient has the appropriate anatomy. However, in patients with severe renal impairment, a higher threshold should be applied for repair because the risks of both open repair and EVAR are significantly higher," Dr. Bao-Ngoc H. Nguyen declared at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

"Chronic renal failure is quite prevalent in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm: up to 30%. It is quite worrisome because any further decline in renal function in these patients could push them toward dialysis. More than that, postoperative renal failure is a predictor for early and late mortality," noted Dr. Nguyen of George Washington University, Washington.

She presented a retrospective study in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm and chronic kidney disease. The aim, she explained, was to answer a key question: "Which one of these two treatment modalities is the lesser of two evils?"

For answers, Dr. Nguyen and coinvestigators turned to the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database for 2005-2010. They identified 3,523 patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-60 mL/minute, who underwent EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm and 1,117 treated via open surgical repair. Another 363 EVAR patients had severe chronic renal insufficiency, with an eGFR of less than 30 mL/minute, as did 139 patients who underwent open repair. Vascular surgeons performed all procedures in this study.

Patients with moderate renal insufficiency who underwent EVAR had markedly lower 30-day rates of mortality, pulmonary complications, cardiovascular events, and postoperative renal dysfunction, including acute kidney injury, than did those who had open surgical repair. One or more adverse events occurred in 6% of the EVAR group, compared with 24.1% of open repair patients. In a multivariate analysis controlled for preoperative differences in the patient groups, those undergoing open repair had an adjusted 4.1-fold greater risk of mortality as well as a 2.2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular events, a 4.2-fold increased risk of renal deterioration including a 5.2-fold greater risk of dialysis, and additional hazards.

In contrast, among the much smaller population of patients with baseline severe chronic renal insufficiency, there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups in terms of 30-day mortality, postoperative renal deterioration, or cardiovascular complications, although pulmonary complications were an adjusted fivefold more likely in the open surgery than among EVAR patients. Of note, rates of all adverse outcomes were markedly higher in both groups than in those with moderate chronic renal insufficiency, such that one or more adverse events occurred in 16.9% of EVAR patients and 42.5% of the open repair patients with severe chronic renal insufficiency.

Discussant Dr. Michael Watkins commented that this study has one glaring shortcoming resulting from a limitation of the NSQIP database.

While NSQIP contains only validated data entered by unbiased, well-trained professionals and NSQIP is "far superior" to the various administrative databases commonly used in evaluating outcomes, it doesn’t include key details about patients’ presenting anatomy, observed Dr. Watkins, director of the vascular research laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

"Was the anatomy really similar in the two groups, or were patients who underwent open repair not candidates for EVAR?" he asked.

Dr. Nguyen conceded that this constitutes a major study limitation, adding that she agrees with Dr. Watkins that anatomy should be the first and foremost factor considered in deciding upon the surgical approach in abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Major Finding: Patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency who underwent open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm had a 4.2-fold greater risk of postoperative renal deterioration than did those who had an endovascular aneurysm repair.

Data Source: A retrospective study of a large national surgical database.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no conflicts of interest.

Surgical educators flag training gaps

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

The source of their ire is a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. Today 80% of graduating general surgery residents seek these year-long fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical areas. The surveyed program directors indicated many trainees arrive unprepared in essential areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Samer Mattar declared in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject matter, said Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar noted in summarizing the survey results.

The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their residency rather than to push their skills to the next level. Among the key survey findings:

• Forty-three percent of program directors felt incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure.

• Thirty percent of incoming fellows couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Fifty-six percent were unable to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly, and 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter were deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

• Nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented.

• Only 51% of program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although fellows did show marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

• A large majority of program directors thought their fellows were disinterested in research and advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

Discussant Dr. Michael G. Sarr was blunt: "This is a scary situation."

"There’s a clear message here from this study: We have a problem. I maintain that we have to stop being bullied by naive, public, politically driven agendas and by some of our own graybeard pundits – and I think we all know who those groups are – and once again take over the control of educating our successors," said Dr. Sarr, professor of surgery at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

He attributed the decline in graduating general surgery residents’ technical skills, patient ownership, and ability to function as trustworthy independent surgeons in large part to the mandated 80-hour maximum work week.

"We all admit and acknowledge that prior to the duty hours reduction of 2003, the expected duty hours most of us trained in were barbaric and often dangerous, and they involved too much scut work. But in the past the final product was superb," Dr. Sarr recalled.

He argued that while it would be folly to return to those days, some flexibility regarding the work hours limit would be beneficial.

"Should our politically driven ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education] and our own RRC [Residency Review Committee] – yes, our own elected overseeing organization – liberalize its rigid, unbending, stringent rules to allow our residents to make more liberal decisions and to develop professionalism by exceeding their 80-hour work restriction when clinical situations demand their presence?" he asked.

Discussant Dr. Frank R. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, said that even though the 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, he doesn’t believe this emotional and contentious issue is the main problem. He noted that at present the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average only two to three per week.

"Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process," Dr. Lewis complained.

He added that nobody should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written ABS exam the first time around is in the mid-30s.

"That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject," the surgeon added.

He asserted that most of the factors responsible for the decline in the competence of graduating general surgery residents are beyond the control of academic surgeons. These factors include the gutting of surgical clerkship opportunities in the fourth year of medical school, along with changes in the surgical landscape that have caused once-popular operations to essentially go away due to technical advances or improved drug therapy.

Discussant Dr. Mark A. Malangoni, associate executive director of the ABS, noted that the more complex open surgery operations previously done by general surgery residents have in many cases been converted to complex laparoscopic procedures that have become the purview of the subspecialty fellowships. Why not abolish the fellowships and drive all those interesting cases and that dedicated training effort back into the residency years? he asked.

That’s not going to happen, Dr. Mattar replied, citing the huge market demand and need for these fellowships.

"They’re very rewarding to all stakeholders," he added.

But constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin to prepare for it then. And there are also efforts to custom-tailor the final year of general surgery residency so that residents can prepare for their fellowship year. Toward that end the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship bound can put their fifth year to the best use.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization with oversight over surgical subspecialty fellowships. Dr. Mattar reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

The source of their ire is a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. Today 80% of graduating general surgery residents seek these year-long fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical areas. The surveyed program directors indicated many trainees arrive unprepared in essential areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Samer Mattar declared in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject matter, said Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar noted in summarizing the survey results.

The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their residency rather than to push their skills to the next level. Among the key survey findings:

• Forty-three percent of program directors felt incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure.

• Thirty percent of incoming fellows couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Fifty-six percent were unable to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly, and 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter were deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

• Nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented.

• Only 51% of program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although fellows did show marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

• A large majority of program directors thought their fellows were disinterested in research and advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

Discussant Dr. Michael G. Sarr was blunt: "This is a scary situation."

"There’s a clear message here from this study: We have a problem. I maintain that we have to stop being bullied by naive, public, politically driven agendas and by some of our own graybeard pundits – and I think we all know who those groups are – and once again take over the control of educating our successors," said Dr. Sarr, professor of surgery at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

He attributed the decline in graduating general surgery residents’ technical skills, patient ownership, and ability to function as trustworthy independent surgeons in large part to the mandated 80-hour maximum work week.

"We all admit and acknowledge that prior to the duty hours reduction of 2003, the expected duty hours most of us trained in were barbaric and often dangerous, and they involved too much scut work. But in the past the final product was superb," Dr. Sarr recalled.

He argued that while it would be folly to return to those days, some flexibility regarding the work hours limit would be beneficial.

"Should our politically driven ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education] and our own RRC [Residency Review Committee] – yes, our own elected overseeing organization – liberalize its rigid, unbending, stringent rules to allow our residents to make more liberal decisions and to develop professionalism by exceeding their 80-hour work restriction when clinical situations demand their presence?" he asked.

Discussant Dr. Frank R. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, said that even though the 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, he doesn’t believe this emotional and contentious issue is the main problem. He noted that at present the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average only two to three per week.

"Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process," Dr. Lewis complained.

He added that nobody should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written ABS exam the first time around is in the mid-30s.

"That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject," the surgeon added.

He asserted that most of the factors responsible for the decline in the competence of graduating general surgery residents are beyond the control of academic surgeons. These factors include the gutting of surgical clerkship opportunities in the fourth year of medical school, along with changes in the surgical landscape that have caused once-popular operations to essentially go away due to technical advances or improved drug therapy.

Discussant Dr. Mark A. Malangoni, associate executive director of the ABS, noted that the more complex open surgery operations previously done by general surgery residents have in many cases been converted to complex laparoscopic procedures that have become the purview of the subspecialty fellowships. Why not abolish the fellowships and drive all those interesting cases and that dedicated training effort back into the residency years? he asked.

That’s not going to happen, Dr. Mattar replied, citing the huge market demand and need for these fellowships.

"They’re very rewarding to all stakeholders," he added.

But constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin to prepare for it then. And there are also efforts to custom-tailor the final year of general surgery residency so that residents can prepare for their fellowship year. Toward that end the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship bound can put their fifth year to the best use.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization with oversight over surgical subspecialty fellowships. Dr. Mattar reported having no financial conflicts.

INDIANAPOLIS – The nation’s elite surgical educators are up in arms over reported widespread deficiencies in the skill set and judgment of recent graduates of 5-year general surgery residencies.

The source of their ire is a detailed new survey of the nation’s subspecialty fellowship program directors. Today 80% of graduating general surgery residents seek these year-long fellowships to obtain advanced training in bariatric, colorectal, thoracic, hepatobiliary, or other surgical areas. The surveyed program directors indicated many trainees arrive unprepared in essential areas.

"Many new fellows must gain basic and fundamental skills at the beginning of their fellowship before they can commence to benefit from the advanced skills that they originally came to obtain. The current high demand for fellowship training and the lack of readiness upon completion of general surgery residencies should be a call to action for all stakeholders in surgical training," Dr. Samer Mattar declared in presenting the survey results at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The survey was conducted by the Fellowship Council, an umbrella organization in charge of standardizing curricula, accrediting programs, and matching residents to fellowships. The group distributed the surveys to all 145 subspecialty fellowship program directors and drew a 63% response rate. That’s considered high for such a lengthy survey and is an indication of the importance educators place on the subject matter, said Dr. Mattar of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

The survey assessed five key educational domains: professionalism, independent practice, psychomotor skills, expertise in their chosen disease state, and scholarly focus.

"Incoming fellows exhibited high levels of professionalism, but there were deficiencies in autonomy and independence, psychomotor abilities, and – most profoundly – academics and scholarship," Dr. Mattar noted in summarizing the survey results.

The underlying theme of the responses is that many fellows are pursuing fellowship positions to make up for inadequacies in their residency rather than to push their skills to the next level. Among the key survey findings:

• Forty-three percent of program directors felt incoming fellows were unable to independently perform half an hour of a major procedure.

• Thirty percent of incoming fellows couldn’t independently perform basic operations such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• Fifty-six percent were unable to laparoscopically suture and tie knots properly, and 26% couldn’t recognize anatomic planes through the laparoscope.

• One-quarter were deemed unable to recognize early signs of complications.

• Nearly 40% of program directors said new fellows display a lack of "patient ownership." "We promote patient ownership in our programs. We are somewhat disappointed and dismayed that the fellows feel that the patient is part of a service and not their own," Dr. Mattar commented.

• Only 51% of program directors indicated their incoming fellows demonstrated independence in the operating room and on call, although fellows did show marked improvement in these areas as the year went on.

• A large majority of program directors thought their fellows were disinterested in research and advancing the field, even though, as Dr. Mattar noted, "This is a mandate in our curriculum."

Discussant Dr. Michael G. Sarr was blunt: "This is a scary situation."

"There’s a clear message here from this study: We have a problem. I maintain that we have to stop being bullied by naive, public, politically driven agendas and by some of our own graybeard pundits – and I think we all know who those groups are – and once again take over the control of educating our successors," said Dr. Sarr, professor of surgery at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn.

He attributed the decline in graduating general surgery residents’ technical skills, patient ownership, and ability to function as trustworthy independent surgeons in large part to the mandated 80-hour maximum work week.

"We all admit and acknowledge that prior to the duty hours reduction of 2003, the expected duty hours most of us trained in were barbaric and often dangerous, and they involved too much scut work. But in the past the final product was superb," Dr. Sarr recalled.

He argued that while it would be folly to return to those days, some flexibility regarding the work hours limit would be beneficial.

"Should our politically driven ACGME [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education] and our own RRC [Residency Review Committee] – yes, our own elected overseeing organization – liberalize its rigid, unbending, stringent rules to allow our residents to make more liberal decisions and to develop professionalism by exceeding their 80-hour work restriction when clinical situations demand their presence?" he asked.

Discussant Dr. Frank R. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, said that even though the 80-hour work limit has effectively subtracted 6-12 months from the general surgery residency, he doesn’t believe this emotional and contentious issue is the main problem. He noted that at present the average number of operations done by a first-year resident is less than two per week, while second-year residents average only two to three per week.

"Our residents are spending 80 hours a week while doing two or three operations per week, which arguably could be done in half a day. It would be hard to imagine a less efficient educational process," Dr. Lewis complained.

He added that nobody should be surprised by the Fellowship Council survey results. During the past decade the failure rate on the American Board of Surgery’s oral exam has climbed steadily from 16% to 28%. At present the percentage of examinees who fail either the oral or written ABS exam the first time around is in the mid-30s.

"That’s arguably an absurd failure rate for a 5-year training program in a group of people who should have mastered the subject," the surgeon added.

He asserted that most of the factors responsible for the decline in the competence of graduating general surgery residents are beyond the control of academic surgeons. These factors include the gutting of surgical clerkship opportunities in the fourth year of medical school, along with changes in the surgical landscape that have caused once-popular operations to essentially go away due to technical advances or improved drug therapy.

Discussant Dr. Mark A. Malangoni, associate executive director of the ABS, noted that the more complex open surgery operations previously done by general surgery residents have in many cases been converted to complex laparoscopic procedures that have become the purview of the subspecialty fellowships. Why not abolish the fellowships and drive all those interesting cases and that dedicated training effort back into the residency years? he asked.

That’s not going to happen, Dr. Mattar replied, citing the huge market demand and need for these fellowships.

"They’re very rewarding to all stakeholders," he added.

But constructive changes are afoot, according to Dr. Mattar. Plans are well underway to change the fourth year of medical school so that students interested in a career in surgery can begin to prepare for it then. And there are also efforts to custom-tailor the final year of general surgery residency so that residents can prepare for their fellowship year. Toward that end the Fellowship Council has moved the fellowship match date up to June so residents who know they are fellowship bound can put their fifth year to the best use.