User login

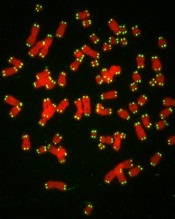

telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

New research indicates that an enzyme called uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG) protects the ends of B-cell chromosomes to facilitate B-cell proliferation in response to infection.

The study also suggests that targeting UNG may help treat certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Ramiro Verdun, PhD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described the study in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers knew that when a B cell first encounters a foreign antigen, it starts to proliferate and produce a DNA-modifying enzyme called activation-induced deaminase (AID).

AID creates mutations in the cell’s immunoglobulin genes so the cell’s progeny produce a diverse array of antibodies that can bind the antigen with high affinity and mediate various immune responses.

But AID can create mutations elsewhere in the B cell’s genome, and, if these mutations are not mended by UNG or other DNA repair proteins, this can lead to NHL and other cancers.

Dr Verdun and his colleagues decided to investigate whether AID targets the telomeres of mouse B cells. They chose this path of investigation because telomeres contain similar DNA sequences to immunoglobulin genes.

The researchers found that, in the absence of UNG, AID created mutations in B-cell telomeres that caused them to rapidly shorten, limiting the proliferation of activated B cells.

UNG helped to repair these mutations, preventing telomere loss and facilitating B-cell expansion. UNG enabled the B cells to continue proliferating while they mutated their immunoglobulin genes, allowing them to mount an effective immune response.

Finally, the researchers found that UNG’s activity may also help NHL cells, which often overexpress AID, to continue proliferating.

The team tested human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells with high or low expression of AID. And they found that inhibiting UNG impaired the growth of DLBCL cells with high AID expression but had no effect on DLBCL cells with low AID expression.

“We show that cancerous human B cells expressing AID require UNG for proliferation, suggesting that targeting UNG may be a means to delay the growth of AID-positive cancers,” Dr Verdun said. ![]()

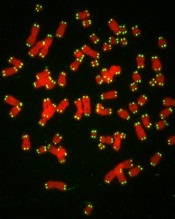

telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

New research indicates that an enzyme called uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG) protects the ends of B-cell chromosomes to facilitate B-cell proliferation in response to infection.

The study also suggests that targeting UNG may help treat certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Ramiro Verdun, PhD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described the study in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers knew that when a B cell first encounters a foreign antigen, it starts to proliferate and produce a DNA-modifying enzyme called activation-induced deaminase (AID).

AID creates mutations in the cell’s immunoglobulin genes so the cell’s progeny produce a diverse array of antibodies that can bind the antigen with high affinity and mediate various immune responses.

But AID can create mutations elsewhere in the B cell’s genome, and, if these mutations are not mended by UNG or other DNA repair proteins, this can lead to NHL and other cancers.

Dr Verdun and his colleagues decided to investigate whether AID targets the telomeres of mouse B cells. They chose this path of investigation because telomeres contain similar DNA sequences to immunoglobulin genes.

The researchers found that, in the absence of UNG, AID created mutations in B-cell telomeres that caused them to rapidly shorten, limiting the proliferation of activated B cells.

UNG helped to repair these mutations, preventing telomere loss and facilitating B-cell expansion. UNG enabled the B cells to continue proliferating while they mutated their immunoglobulin genes, allowing them to mount an effective immune response.

Finally, the researchers found that UNG’s activity may also help NHL cells, which often overexpress AID, to continue proliferating.

The team tested human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells with high or low expression of AID. And they found that inhibiting UNG impaired the growth of DLBCL cells with high AID expression but had no effect on DLBCL cells with low AID expression.

“We show that cancerous human B cells expressing AID require UNG for proliferation, suggesting that targeting UNG may be a means to delay the growth of AID-positive cancers,” Dr Verdun said. ![]()

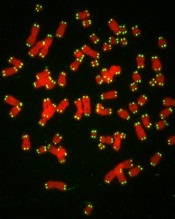

telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

New research indicates that an enzyme called uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG) protects the ends of B-cell chromosomes to facilitate B-cell proliferation in response to infection.

The study also suggests that targeting UNG may help treat certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Ramiro Verdun, PhD, of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami in Florida, and his colleagues described the study in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers knew that when a B cell first encounters a foreign antigen, it starts to proliferate and produce a DNA-modifying enzyme called activation-induced deaminase (AID).

AID creates mutations in the cell’s immunoglobulin genes so the cell’s progeny produce a diverse array of antibodies that can bind the antigen with high affinity and mediate various immune responses.

But AID can create mutations elsewhere in the B cell’s genome, and, if these mutations are not mended by UNG or other DNA repair proteins, this can lead to NHL and other cancers.

Dr Verdun and his colleagues decided to investigate whether AID targets the telomeres of mouse B cells. They chose this path of investigation because telomeres contain similar DNA sequences to immunoglobulin genes.

The researchers found that, in the absence of UNG, AID created mutations in B-cell telomeres that caused them to rapidly shorten, limiting the proliferation of activated B cells.

UNG helped to repair these mutations, preventing telomere loss and facilitating B-cell expansion. UNG enabled the B cells to continue proliferating while they mutated their immunoglobulin genes, allowing them to mount an effective immune response.

Finally, the researchers found that UNG’s activity may also help NHL cells, which often overexpress AID, to continue proliferating.

The team tested human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells with high or low expression of AID. And they found that inhibiting UNG impaired the growth of DLBCL cells with high AID expression but had no effect on DLBCL cells with low AID expression.

“We show that cancerous human B cells expressing AID require UNG for proliferation, suggesting that targeting UNG may be a means to delay the growth of AID-positive cancers,” Dr Verdun said. ![]()