User login

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

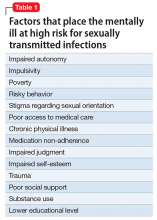

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.

Diagnosing STIs

To diagnose an STI, first a clinician must consider its likelihood. Taking a thorough sexual history allows assessment of the need for further investigation and provides an opportunity to discuss risk reduction. In accordance with recent guidelines,8 all health care providers are encouraged to consider the sexual history a routine aspect of the clinical encounter. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) “Five Ps” approach (Table 2) is an excellent tool for guiding investigation and counseling.9

The Figure provides health care providers with an algorithm to guide testing for STIs among psychiatric patients. Note that chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, chancroid, viral hepatitis, and HIV must be reported to state public health agencies and the CDC.

Modern laboratory techniques make diagnosing STIs easier. Analysis of urine or serum reduces the need for invasive sampling. If swabs are required for diagnosis, patient self-collection of urethral, vulvovaginal, rectal, or pharyngeal specimens is as accurate as clinician collected samples and is better tolerated.8 Because of variation in diagnostic assays, we recommend contacting the laboratory before sending non-standard samples to ensure accurate collection and analysis.

Guidelines for preventing and screening for STIs

There are no prevention guidelines for STIs specific to the psychiatric population, although there is a clear need for focused intervention in this vulnerable patient group.10 Rates of STI screening generally are low in the psychiatric setting,11 which results in a considerable burden of disease. All psychiatric patients should be encouraged to engage with STI screening programs that are in line with national guidelines. In the inpatient psychiatric or medical environment, clinicians have a responsibility to ensure that STI screening is considered for each patient.

Patients with mental illness should be assumed to be sexually active, even if they do not volunteer this information to clinicians. Employ a low threshold for recommending safer sex practices including condom use. Encourage women to develop a relationship with a family practitioner, internist, or gynecologist. Advise men who have sex with men (MSM) to visit a doctor regularly for screening of HIV and rectal, anal, and oral STIs as behavior and symptoms dictate.

There is general agreement about STI screening among the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), CDC, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. USPSTF guidelines are summarized in Table 3.12

In addition to these guidelines, the CDC suggests that all adults and adolescents be tested at least once for HIV.13 The CDC also recommends annual testing of MSM for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. In MSM who have multiple partners or who have sex while using illicit drugs, testing should occur more frequently, such as every 3 to 6 months.14

HPV. Routine HPV screening is not recommended; however, 2 vaccines are available to prevent oncogenic HPV (types 16 and 18). All females age 13 to 26 should receive 3 doses of HPV vaccine over a 6-month period. The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts and is preferred when available. Males age 9 to 26 also can receive the vaccine, although ideally it should be administered before sexual activity begins.15 Women still should attend routine cervical cancer screening even if they have the vaccine because 30% of cervical cancers are not caused by HPV 16/18. However, this means that 70% of cervical cancers are associated with HPV 16/18, making screening and the vaccine an important public health initiative. There also is a link between HPV and oral cancers.

Treating STIs among mentally ill individuals

Treatment of STIs among mentally ill individuals is important to prevent medical complications and to reduce transmission. Here are a few additional questions to keep in mind when treating a patient with psychiatric illness:

Does the patient have a primary psychiatric disorder, or is the patient’s current psychiatric presentation a result of the infection?

Some STIs can manifest with psychiatric symptoms—for example, neurosyphilis and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders—and pose a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining a longitudinal history of the patient’s mental health, age of onset, and family history can help clarify the cause.

Are there any psychiatric adverse effects of STI treatment?

Most drugs used for treating common STIs are not known to cause psychiatric adverse effects (See the American Psychiatric Association16 and Sockalingham et al17 for a thorough discussion of HIV and hepatitis C treatment). The exception is fluoroquinolones, which could be prescribed for PID if cephalosporin therapy is not feasible. CNS effects of fluoroquinolones include insomnia, restlessness, confusion, and, in rare cases, mania and psychosis.

What are possible medication interactions to keep in mind when treating a psychiatric patient?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other than sulindac, could increase serum lithium levels. Although NSAIDs are not contraindicated in patients taking lithium, other pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, may be preferred as a first-line choice.

Carbamazepine could lower serum levels of doxycycline.18

Azithromycin and other macrolides, as well as fluoroquinolones, could have QTc prolonging effects and has been associated with torsades de pointes.19 Several psychiatric medications, in particular, atypical antipsychotics, also could prolong the QTc interval. This could be a consideration in patients with underlying long QT intervals at baseline or a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Psychiatric patients might refuse or not adhere to their medication. Refusals could be the result of grandiose delusions (“I don’t need treatment”) or paranoia (“The doctor is trying to poison me”). Consider 1-time doses of antibiotics that can be given in the clinic for uncomplicated infections when adherence is an issue. Because psychiatric patients are at higher risk for acquiring STIs, education and counseling—especially substance abuse counseling—are vital as both primary and secondary prevention strategies. Treatment of STIs should be accompanied by referrals to the social work team or a therapist when appropriate.

Finally, as with any proposed treatment, it is important to consider whether the patient has capacity to consent to or refuse treatment. To assess for capacity, a patient must be able to:

- communicate a choice

- understand the relevant information

- appreciate the medical consequences of the decision

- demonstrate the ability to reason about treatment choices.20

Case continued

In the emergency department, Ms. K’s vital signs are: temperature 39.5°C; pulse 110 beats per minute; blood pressure 96/67 mm Hg; and breathing 20 respirations per minute. She complains of nausea and has 2 episodes of emesis. She allows clinicians to perform a complete physical examination, including pelvic exam. Her cervix is inflamed, and she is noted to have adnexal and cervical motion tenderness.

Labs and imaging confirm a diagnosis of PID due to gonorrhea and she is admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics. She continues to experience nausea and vomiting, but also complains of dizziness and diarrhea. Her speech is slurred and a coarse tremor is noticed in her hands. Renal function tests show slight impairment, probably due to dehydration. A pregnancy test is negative.

Lithium is held. Her nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea resolve quickly, and Ms. K asks to leave. When she is told that she is not ready for discharge, Ms. K becomes upset and rips out her IV yelling, “I don’t need treatment from you guys!” A psychiatry consult is called to assess for her capacity to refuse treatment. The team determines that she has capacity, but she becomes agreeable to remaining in the hospital after a phone conversation with her community mental health team.

Ms. K improves with antibiotic treatment. HIV and syphilis serology tests are negative. Before discharge, both the community psychiatrist and her primary care physicians are informed her lithium was held during hospitalization and restarted before discharge. Ms. K also is educated about the signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, as well as common STIs.

Clinical considerations

- Physicians should have a low threshold of suspicion for PID in a sexually active young woman who presents with abdominal pain and shuffling gait, which is a natural attempt to reduce cervical irritation and is associated with PID.

- Ask about sexual history and symptoms of STIs.

- Rule out STIs in men presenting with urinary tract infections.

- If chlamydia is diagnosed, treatment for gonorrhea also is essential, and vice versa.

- Always think about HIV and hepatatis B and C in a patient with a STI.

- Treatment with single-dose medications can be effective.

- Risk of STIs is higher during episodes of mania or psychosis.

- Consider hospitalization if medically indicated or if you suspect non-adherence to therapy. It is important to remember that all kinds of systemic infections—including PID—can result in dehydration and alter renal metabolism leading to lithium accumulation.

- Mentally ill patients might require placement under involuntary commitment if they are found to be a danger to themselves or others. It is important to liaise with both the community psychiatry team and primary care physician both during hospitalization and before discharge to ensure a smooth transition.

1. Fenton KA, Lowndes CM. Recent trends in the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the European Union. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(4):255-263.

2. Trigg BG, Kerndt PR, Aynalem G. Sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(5):1083-1113, x.

3. Frenkl TL, Potts J. Sexually transmitted infections. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):33-46; vi.

4. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6-10.

5. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

6. King C, Feldman J, Waithaka Y, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection prevalence in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(10):877-882.

7. Erbelding EJ, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and their association with sexually transmitted disease risk. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(1):8-12.

8. Freeman AH, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Evaluation of self-collected versus clinician-collected swabs for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae pharyngeal infection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1036-1039.

9. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

10. Rein DB, Anderson LA, Irwin KL. Mental health disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a privately insured population. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(12):917-924.

11. Rothbard AB, Blank MB, Staab JP, et al. Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):534-537.

12. Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, et al. USPSTF recommendations for STI screening. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(6):819-824.

13. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17; quiz CE1-CE 4.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/incidence-prevalence-and-cost-sexually-transmitted-infections-united-states. Published February 2013. Accessed December 12, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705-1708.

16. American Psychiatric Association. HIV psychiatry. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/hiv-psychiatry. Accessed December 13, 2016.

17. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

18. Neuvonen PJ, Pentikäinen PJ, Gothoni G. Inhibition of iron absorption by tetracycline. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;2(1):94-96.

19. Sears SP, Getz TW, Austin CO, et al. Incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with prolonged QTc after the administration of azithromycin: a retrospective study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3:99-105.

20. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.

Diagnosing STIs

To diagnose an STI, first a clinician must consider its likelihood. Taking a thorough sexual history allows assessment of the need for further investigation and provides an opportunity to discuss risk reduction. In accordance with recent guidelines,8 all health care providers are encouraged to consider the sexual history a routine aspect of the clinical encounter. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) “Five Ps” approach (Table 2) is an excellent tool for guiding investigation and counseling.9

The Figure provides health care providers with an algorithm to guide testing for STIs among psychiatric patients. Note that chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, chancroid, viral hepatitis, and HIV must be reported to state public health agencies and the CDC.

Modern laboratory techniques make diagnosing STIs easier. Analysis of urine or serum reduces the need for invasive sampling. If swabs are required for diagnosis, patient self-collection of urethral, vulvovaginal, rectal, or pharyngeal specimens is as accurate as clinician collected samples and is better tolerated.8 Because of variation in diagnostic assays, we recommend contacting the laboratory before sending non-standard samples to ensure accurate collection and analysis.

Guidelines for preventing and screening for STIs

There are no prevention guidelines for STIs specific to the psychiatric population, although there is a clear need for focused intervention in this vulnerable patient group.10 Rates of STI screening generally are low in the psychiatric setting,11 which results in a considerable burden of disease. All psychiatric patients should be encouraged to engage with STI screening programs that are in line with national guidelines. In the inpatient psychiatric or medical environment, clinicians have a responsibility to ensure that STI screening is considered for each patient.

Patients with mental illness should be assumed to be sexually active, even if they do not volunteer this information to clinicians. Employ a low threshold for recommending safer sex practices including condom use. Encourage women to develop a relationship with a family practitioner, internist, or gynecologist. Advise men who have sex with men (MSM) to visit a doctor regularly for screening of HIV and rectal, anal, and oral STIs as behavior and symptoms dictate.

There is general agreement about STI screening among the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), CDC, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. USPSTF guidelines are summarized in Table 3.12

In addition to these guidelines, the CDC suggests that all adults and adolescents be tested at least once for HIV.13 The CDC also recommends annual testing of MSM for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. In MSM who have multiple partners or who have sex while using illicit drugs, testing should occur more frequently, such as every 3 to 6 months.14

HPV. Routine HPV screening is not recommended; however, 2 vaccines are available to prevent oncogenic HPV (types 16 and 18). All females age 13 to 26 should receive 3 doses of HPV vaccine over a 6-month period. The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts and is preferred when available. Males age 9 to 26 also can receive the vaccine, although ideally it should be administered before sexual activity begins.15 Women still should attend routine cervical cancer screening even if they have the vaccine because 30% of cervical cancers are not caused by HPV 16/18. However, this means that 70% of cervical cancers are associated with HPV 16/18, making screening and the vaccine an important public health initiative. There also is a link between HPV and oral cancers.

Treating STIs among mentally ill individuals

Treatment of STIs among mentally ill individuals is important to prevent medical complications and to reduce transmission. Here are a few additional questions to keep in mind when treating a patient with psychiatric illness:

Does the patient have a primary psychiatric disorder, or is the patient’s current psychiatric presentation a result of the infection?

Some STIs can manifest with psychiatric symptoms—for example, neurosyphilis and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders—and pose a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining a longitudinal history of the patient’s mental health, age of onset, and family history can help clarify the cause.

Are there any psychiatric adverse effects of STI treatment?

Most drugs used for treating common STIs are not known to cause psychiatric adverse effects (See the American Psychiatric Association16 and Sockalingham et al17 for a thorough discussion of HIV and hepatitis C treatment). The exception is fluoroquinolones, which could be prescribed for PID if cephalosporin therapy is not feasible. CNS effects of fluoroquinolones include insomnia, restlessness, confusion, and, in rare cases, mania and psychosis.

What are possible medication interactions to keep in mind when treating a psychiatric patient?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other than sulindac, could increase serum lithium levels. Although NSAIDs are not contraindicated in patients taking lithium, other pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, may be preferred as a first-line choice.

Carbamazepine could lower serum levels of doxycycline.18

Azithromycin and other macrolides, as well as fluoroquinolones, could have QTc prolonging effects and has been associated with torsades de pointes.19 Several psychiatric medications, in particular, atypical antipsychotics, also could prolong the QTc interval. This could be a consideration in patients with underlying long QT intervals at baseline or a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Psychiatric patients might refuse or not adhere to their medication. Refusals could be the result of grandiose delusions (“I don’t need treatment”) or paranoia (“The doctor is trying to poison me”). Consider 1-time doses of antibiotics that can be given in the clinic for uncomplicated infections when adherence is an issue. Because psychiatric patients are at higher risk for acquiring STIs, education and counseling—especially substance abuse counseling—are vital as both primary and secondary prevention strategies. Treatment of STIs should be accompanied by referrals to the social work team or a therapist when appropriate.

Finally, as with any proposed treatment, it is important to consider whether the patient has capacity to consent to or refuse treatment. To assess for capacity, a patient must be able to:

- communicate a choice

- understand the relevant information

- appreciate the medical consequences of the decision

- demonstrate the ability to reason about treatment choices.20

Case continued

In the emergency department, Ms. K’s vital signs are: temperature 39.5°C; pulse 110 beats per minute; blood pressure 96/67 mm Hg; and breathing 20 respirations per minute. She complains of nausea and has 2 episodes of emesis. She allows clinicians to perform a complete physical examination, including pelvic exam. Her cervix is inflamed, and she is noted to have adnexal and cervical motion tenderness.

Labs and imaging confirm a diagnosis of PID due to gonorrhea and she is admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics. She continues to experience nausea and vomiting, but also complains of dizziness and diarrhea. Her speech is slurred and a coarse tremor is noticed in her hands. Renal function tests show slight impairment, probably due to dehydration. A pregnancy test is negative.

Lithium is held. Her nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea resolve quickly, and Ms. K asks to leave. When she is told that she is not ready for discharge, Ms. K becomes upset and rips out her IV yelling, “I don’t need treatment from you guys!” A psychiatry consult is called to assess for her capacity to refuse treatment. The team determines that she has capacity, but she becomes agreeable to remaining in the hospital after a phone conversation with her community mental health team.

Ms. K improves with antibiotic treatment. HIV and syphilis serology tests are negative. Before discharge, both the community psychiatrist and her primary care physicians are informed her lithium was held during hospitalization and restarted before discharge. Ms. K also is educated about the signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, as well as common STIs.

Clinical considerations

- Physicians should have a low threshold of suspicion for PID in a sexually active young woman who presents with abdominal pain and shuffling gait, which is a natural attempt to reduce cervical irritation and is associated with PID.

- Ask about sexual history and symptoms of STIs.

- Rule out STIs in men presenting with urinary tract infections.

- If chlamydia is diagnosed, treatment for gonorrhea also is essential, and vice versa.

- Always think about HIV and hepatatis B and C in a patient with a STI.

- Treatment with single-dose medications can be effective.

- Risk of STIs is higher during episodes of mania or psychosis.

- Consider hospitalization if medically indicated or if you suspect non-adherence to therapy. It is important to remember that all kinds of systemic infections—including PID—can result in dehydration and alter renal metabolism leading to lithium accumulation.

- Mentally ill patients might require placement under involuntary commitment if they are found to be a danger to themselves or others. It is important to liaise with both the community psychiatry team and primary care physician both during hospitalization and before discharge to ensure a smooth transition.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.

Diagnosing STIs

To diagnose an STI, first a clinician must consider its likelihood. Taking a thorough sexual history allows assessment of the need for further investigation and provides an opportunity to discuss risk reduction. In accordance with recent guidelines,8 all health care providers are encouraged to consider the sexual history a routine aspect of the clinical encounter. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) “Five Ps” approach (Table 2) is an excellent tool for guiding investigation and counseling.9

The Figure provides health care providers with an algorithm to guide testing for STIs among psychiatric patients. Note that chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, chancroid, viral hepatitis, and HIV must be reported to state public health agencies and the CDC.

Modern laboratory techniques make diagnosing STIs easier. Analysis of urine or serum reduces the need for invasive sampling. If swabs are required for diagnosis, patient self-collection of urethral, vulvovaginal, rectal, or pharyngeal specimens is as accurate as clinician collected samples and is better tolerated.8 Because of variation in diagnostic assays, we recommend contacting the laboratory before sending non-standard samples to ensure accurate collection and analysis.

Guidelines for preventing and screening for STIs

There are no prevention guidelines for STIs specific to the psychiatric population, although there is a clear need for focused intervention in this vulnerable patient group.10 Rates of STI screening generally are low in the psychiatric setting,11 which results in a considerable burden of disease. All psychiatric patients should be encouraged to engage with STI screening programs that are in line with national guidelines. In the inpatient psychiatric or medical environment, clinicians have a responsibility to ensure that STI screening is considered for each patient.

Patients with mental illness should be assumed to be sexually active, even if they do not volunteer this information to clinicians. Employ a low threshold for recommending safer sex practices including condom use. Encourage women to develop a relationship with a family practitioner, internist, or gynecologist. Advise men who have sex with men (MSM) to visit a doctor regularly for screening of HIV and rectal, anal, and oral STIs as behavior and symptoms dictate.

There is general agreement about STI screening among the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), CDC, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. USPSTF guidelines are summarized in Table 3.12

In addition to these guidelines, the CDC suggests that all adults and adolescents be tested at least once for HIV.13 The CDC also recommends annual testing of MSM for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. In MSM who have multiple partners or who have sex while using illicit drugs, testing should occur more frequently, such as every 3 to 6 months.14

HPV. Routine HPV screening is not recommended; however, 2 vaccines are available to prevent oncogenic HPV (types 16 and 18). All females age 13 to 26 should receive 3 doses of HPV vaccine over a 6-month period. The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) also protects against HPV types 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts and is preferred when available. Males age 9 to 26 also can receive the vaccine, although ideally it should be administered before sexual activity begins.15 Women still should attend routine cervical cancer screening even if they have the vaccine because 30% of cervical cancers are not caused by HPV 16/18. However, this means that 70% of cervical cancers are associated with HPV 16/18, making screening and the vaccine an important public health initiative. There also is a link between HPV and oral cancers.

Treating STIs among mentally ill individuals

Treatment of STIs among mentally ill individuals is important to prevent medical complications and to reduce transmission. Here are a few additional questions to keep in mind when treating a patient with psychiatric illness:

Does the patient have a primary psychiatric disorder, or is the patient’s current psychiatric presentation a result of the infection?

Some STIs can manifest with psychiatric symptoms—for example, neurosyphilis and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders—and pose a diagnostic challenge. Obtaining a longitudinal history of the patient’s mental health, age of onset, and family history can help clarify the cause.

Are there any psychiatric adverse effects of STI treatment?

Most drugs used for treating common STIs are not known to cause psychiatric adverse effects (See the American Psychiatric Association16 and Sockalingham et al17 for a thorough discussion of HIV and hepatitis C treatment). The exception is fluoroquinolones, which could be prescribed for PID if cephalosporin therapy is not feasible. CNS effects of fluoroquinolones include insomnia, restlessness, confusion, and, in rare cases, mania and psychosis.

What are possible medication interactions to keep in mind when treating a psychiatric patient?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), other than sulindac, could increase serum lithium levels. Although NSAIDs are not contraindicated in patients taking lithium, other pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, may be preferred as a first-line choice.

Carbamazepine could lower serum levels of doxycycline.18

Azithromycin and other macrolides, as well as fluoroquinolones, could have QTc prolonging effects and has been associated with torsades de pointes.19 Several psychiatric medications, in particular, atypical antipsychotics, also could prolong the QTc interval. This could be a consideration in patients with underlying long QT intervals at baseline or a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Psychiatric patients might refuse or not adhere to their medication. Refusals could be the result of grandiose delusions (“I don’t need treatment”) or paranoia (“The doctor is trying to poison me”). Consider 1-time doses of antibiotics that can be given in the clinic for uncomplicated infections when adherence is an issue. Because psychiatric patients are at higher risk for acquiring STIs, education and counseling—especially substance abuse counseling—are vital as both primary and secondary prevention strategies. Treatment of STIs should be accompanied by referrals to the social work team or a therapist when appropriate.

Finally, as with any proposed treatment, it is important to consider whether the patient has capacity to consent to or refuse treatment. To assess for capacity, a patient must be able to:

- communicate a choice

- understand the relevant information

- appreciate the medical consequences of the decision

- demonstrate the ability to reason about treatment choices.20

Case continued

In the emergency department, Ms. K’s vital signs are: temperature 39.5°C; pulse 110 beats per minute; blood pressure 96/67 mm Hg; and breathing 20 respirations per minute. She complains of nausea and has 2 episodes of emesis. She allows clinicians to perform a complete physical examination, including pelvic exam. Her cervix is inflamed, and she is noted to have adnexal and cervical motion tenderness.

Labs and imaging confirm a diagnosis of PID due to gonorrhea and she is admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics. She continues to experience nausea and vomiting, but also complains of dizziness and diarrhea. Her speech is slurred and a coarse tremor is noticed in her hands. Renal function tests show slight impairment, probably due to dehydration. A pregnancy test is negative.

Lithium is held. Her nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea resolve quickly, and Ms. K asks to leave. When she is told that she is not ready for discharge, Ms. K becomes upset and rips out her IV yelling, “I don’t need treatment from you guys!” A psychiatry consult is called to assess for her capacity to refuse treatment. The team determines that she has capacity, but she becomes agreeable to remaining in the hospital after a phone conversation with her community mental health team.

Ms. K improves with antibiotic treatment. HIV and syphilis serology tests are negative. Before discharge, both the community psychiatrist and her primary care physicians are informed her lithium was held during hospitalization and restarted before discharge. Ms. K also is educated about the signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, as well as common STIs.

Clinical considerations

- Physicians should have a low threshold of suspicion for PID in a sexually active young woman who presents with abdominal pain and shuffling gait, which is a natural attempt to reduce cervical irritation and is associated with PID.

- Ask about sexual history and symptoms of STIs.

- Rule out STIs in men presenting with urinary tract infections.

- If chlamydia is diagnosed, treatment for gonorrhea also is essential, and vice versa.

- Always think about HIV and hepatatis B and C in a patient with a STI.

- Treatment with single-dose medications can be effective.

- Risk of STIs is higher during episodes of mania or psychosis.

- Consider hospitalization if medically indicated or if you suspect non-adherence to therapy. It is important to remember that all kinds of systemic infections—including PID—can result in dehydration and alter renal metabolism leading to lithium accumulation.

- Mentally ill patients might require placement under involuntary commitment if they are found to be a danger to themselves or others. It is important to liaise with both the community psychiatry team and primary care physician both during hospitalization and before discharge to ensure a smooth transition.

1. Fenton KA, Lowndes CM. Recent trends in the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the European Union. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(4):255-263.

2. Trigg BG, Kerndt PR, Aynalem G. Sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(5):1083-1113, x.

3. Frenkl TL, Potts J. Sexually transmitted infections. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):33-46; vi.

4. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6-10.

5. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

6. King C, Feldman J, Waithaka Y, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection prevalence in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(10):877-882.

7. Erbelding EJ, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and their association with sexually transmitted disease risk. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(1):8-12.

8. Freeman AH, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Evaluation of self-collected versus clinician-collected swabs for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae pharyngeal infection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1036-1039.

9. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

10. Rein DB, Anderson LA, Irwin KL. Mental health disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a privately insured population. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(12):917-924.

11. Rothbard AB, Blank MB, Staab JP, et al. Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):534-537.

12. Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, et al. USPSTF recommendations for STI screening. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(6):819-824.

13. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17; quiz CE1-CE 4.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/incidence-prevalence-and-cost-sexually-transmitted-infections-united-states. Published February 2013. Accessed December 12, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705-1708.

16. American Psychiatric Association. HIV psychiatry. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/hiv-psychiatry. Accessed December 13, 2016.

17. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

18. Neuvonen PJ, Pentikäinen PJ, Gothoni G. Inhibition of iron absorption by tetracycline. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;2(1):94-96.

19. Sears SP, Getz TW, Austin CO, et al. Incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with prolonged QTc after the administration of azithromycin: a retrospective study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3:99-105.

20. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

1. Fenton KA, Lowndes CM. Recent trends in the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the European Union. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(4):255-263.

2. Trigg BG, Kerndt PR, Aynalem G. Sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease in women. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(5):1083-1113, x.

3. Frenkl TL, Potts J. Sexually transmitted infections. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35(1):33-46; vi.

4. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6-10.

5. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

6. King C, Feldman J, Waithaka Y, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection prevalence in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(10):877-882.

7. Erbelding EJ, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in sexually transmitted disease clinic patients and their association with sexually transmitted disease risk. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(1):8-12.

8. Freeman AH, Bernstein KT, Kohn RP, et al. Evaluation of self-collected versus clinician-collected swabs for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae pharyngeal infection among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(11):1036-1039.

9. Workowski KA, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

10. Rein DB, Anderson LA, Irwin KL. Mental health disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a privately insured population. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(12):917-924.

11. Rothbard AB, Blank MB, Staab JP, et al. Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):534-537.

12. Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, et al. USPSTF recommendations for STI screening. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(6):819-824.

13. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17; quiz CE1-CE 4.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/incidence-prevalence-and-cost-sexually-transmitted-infections-united-states. Published February 2013. Accessed December 12, 2016.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(50):1705-1708.

16. American Psychiatric Association. HIV psychiatry. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/hiv-psychiatry. Accessed December 13, 2016.

17. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

18. Neuvonen PJ, Pentikäinen PJ, Gothoni G. Inhibition of iron absorption by tetracycline. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;2(1):94-96.

19. Sears SP, Getz TW, Austin CO, et al. Incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with prolonged QTc after the administration of azithromycin: a retrospective study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3:99-105.

20. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.