User login

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

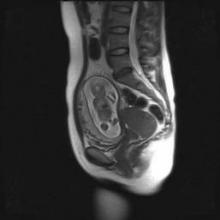

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."

The stress of a cancer diagnosis during a desired pregnancy is very hard on patients, Dr. Temkin added. "Pregnancy is a time when many women come to grips with their own mortality as well as that of giving new life. Adding a diagnosis of cancer of top of that – especially in the face of a much-desired pregnancy – can be devastating."

These women are faced with two options: terminate the pregnancy and concentrate on their own treatment, or continue the pregnancy knowing that their unborn child will be exposed to the possible risks of radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. Either option can "inflict terrible guilt on a pregnant woman. We can try to minimize that to some degree, but it’s important to know from the outset that what is the right solution for one patient is not right for the next."

Connecting with other women who have experienced the same situation can be of immense value, Dr. Cardonick said. She participates in an online support group called "Hope for Two."

The organization’s main goal is to link new patients with survivors who can help educate them as well as lend emotional support. Patients call in or fill out a secure online request for a personal match-up with a survivor, who is often a woman who has had the same type of cancer.

The website also contains links to news and medical articles, books, and financial assistance sources, and allows new patients to securely contact Dr. Cardonick’s pregnancy registry. "We keep in touch with the baby’s pediatrician and the mom every year, to see how things are going and [to] collect information," she said. "The best way to treat these women in the future depends on the information we continue to gather in the present."

None of the researchers interviewed for this article had any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Litton noted that she had no financial disclosures for her 2011 ASCO poster.