User login

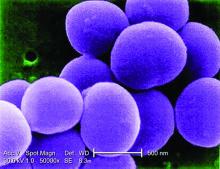

MALMO, SWEDEN – Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus gets the blame in the Americas as the main cause of a great wave of community-acquired severe invasive staphylococcal infections in children and adolescents during the past nearly 2 decades, but many European pediatric infectious disease specialists believe that Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a frequent co-traveler with MRSA, is the true bad actor.

“The American literature focused first on MRSA, but we’ve seen very similar, very severe cases with MSSA [methicillin-susceptible S. aureus] PVL-positive and MRSA PVL-positive infections,” Pablo Rojo, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“It is only because at the beginning there were so many MRSA cases in the States that they thought that was the driver of the disease. It is still unclear. There is still a discussion. But I wanted to bring you my opinion and that of many other authors that it’s mostly PVL-associated,” added Dr. Rojo of Complutense University in Madrid.

He was senior author of a multinational European and Israeli prospective study of risk factors associated with the severity of invasive community-acquired S. aureus infections in children, with invasive infection being defined as hospitalization for an infection with S. aureus isolated from a normally sterile body site such as blood, bone, or cerebrospinal fluid, or S. aureus pneumonia. They identified 152 affected children, 17% of whom had severe community-acquired invasive S. aureus, defined by death or admission to a pediatric intensive care unit due to respiratory failure or hemodynamic instability.

The prevalence of PVL-positive S. aureus infection in the overall invasive infection group was 19%, while 8% of the isolates were MRSA. while MRSA was not associated with a significantly increased risk. The other independent risk factors for severe outcome were pneumonia, with an adjusted 13-fold increased risk, and leukopenia at admission, with an associated 18-fold risk (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 Jul;22[7]:643.e1-6.).

Of note, the virulence of PVL stems from the pore-forming toxin’s ability to lyse white blood cells. Because a leukocyte count is always available once a patient reaches the ED, severe leukopenia as defined by a count of less than 3,000 cells/mm3 at admission becomes a useful early marker of the likely severity of any case of S. aureus invasive disease, according to Dr. Rojo.

He highlighted four key syndromes involving severe invasive S. aureus infection in previously healthy children and adolescents that entail a high likelihood of being PVL positive and should cause physicians to run – not walk – to start appropriate empiric therapy. He also described the treatment regimen that he and other European thought leaders recommend for severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections.

The microbiologic diagnosis of PVL can be made by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) to detect the toxin in an S. aureus isolate, by a rapid monoclonal antibody test, or by polymerase chain reaction to detect PVL genes in an S. aureus isolate. But don’t wait for test results to initiate treatment because these are high-mortality syndromes, he advised.

“Many people tell me, ‘My lab doesn’t have a way to diagnose PVL.’ And it’s true, it’s not available in real life at many hospitals. My message to you is that you don’t need to wait for a microbiological diagnosis or the results to come back from a sample you have sent to the reference lab in the main referral center. We can base our diagnosis and decision to treat on clinical grounds if we focus on these four very uncommon syndromes involving invasive S. aureus infection. I think if you have any child with these symptoms you have to manage them on the assumption that PVL is present,” said Dr. Rojo, principal investigator of the European Project on Invasive S. aureus Pediatric Infections.

The four key syndromes

The four syndromes are severe S. aureus pneumonia, S. aureus bone and joint infections with multiple foci, S. aureus osteomyelitis complicated by deep vein thrombosis, and invasive S. aureus infection plus shock.

- Severe S. aureus pneumonia. Investigators at Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France, have done extensive pioneering work on severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections in children. In an early paper, they highlighted the characteristics that distinguish severe PVL-positive pneumonia: it typically occurs in previously healthy children and adolescents without underlying comorbid conditions, and it is often preceded by a influenza-like syndrome followed by an acute severe pneumonia with hemoptysis. Mortality was very high in this early series, with nearly half of the patients being dead within the first several days after admission (Lancet. 2002 Mar 2;359[9308]:753-9).

- Severe osteomyelitis. Investigators at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, were among the first to observe that osteomyelitis caused by PVL-positive strains of S. aureus are associated with more severe local disease, with multiple affected areas, bigger abscesses, a greater systemic inflammatory response, and more surgeries required compared with osteomyelitis caused by PVL-negative S. aureus (Pediatrics. 2006 Feb;117[2]:433-40).

- Osteomyelitis with deep vein thrombosis. When a child hospitalized for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis due to S. aureus develops difficulty breathing, that’s a red flag for a severe PVL-positive infection involving deep vein thrombosis. Indeed, investigators at the Leeds (England) General Infirmary have reported that deep vein thrombosis in the setting of S. aureus osteomyelitis is associated with a greater than eightfold increased likelihood of a PVL-positive infection (Br J Hosp Med [Lond]. 2015 Jan;76[1]:18-24). Also, patients with PVL-positive osteomyelitis and deep vein thrombosis are prone to formation of septic emboli.

- Osteomyelitis with septic shock. The Lyon group compared outcomes in 14 pediatric patients with PVL-positive S. aureus osteomyelitis and a control group of 17 patients with PVL-negative disease. All 14 PVL-positive patients had severe sepsis and 6 of them had septic shock. In contrast, none of the controls did. Median duration of hospitalization was 46 days in the PVL-positive group, compared with 13 days in controls (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007 Nov;26[11]:1042-8).

Treatment

No randomized trials exist to guide treatment, but Dr. Rojo recommends the protocol utilized by the Lyon group: a bactericidal antibiotic – vancomycin or a beta-lactam – to take on the S. aureus, coupled with a ribosomally active antibiotic – clindamycin or linezolid – to suppress the PVL toxin’s virulence expression. The French group cites both in vitro and in vivo evidence that clindamycin and linezolid in their standard dosing have such an antitoxin effect (Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017 Oct;30[4]:887-917).

In addition, Dr. Rojo recommends utilizing any of the commercially available intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products on the basis of work by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who have demonstrated that these products contain functional neutralizing antibodies against S. aureus leukocidins. This observation provides a likely explanation for anecdotal reports of improved outcomes in IVIG-treated patients with toxin-associated staphylococcal disease (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Oct 24;61[11]. pii: e00968-17).

Challenged as to when specifically he would use IVIG in light of the global shortage of immunoglobulins, Dr. Rojo replied: “Not in every invasive S. aureus infection, but in serious infections that are PVL positive. I think if you have a child with one of these four syndromes who is in a pediatric ICU, you should use it. I mean, the mortality is around 30% in healthy children, so you would not stop from giving it. The risk of giving IVIG is very low, no side effects, so I highly recommend it for these severe cases.”

He reported having no financial conflicts.

MALMO, SWEDEN – Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus gets the blame in the Americas as the main cause of a great wave of community-acquired severe invasive staphylococcal infections in children and adolescents during the past nearly 2 decades, but many European pediatric infectious disease specialists believe that Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a frequent co-traveler with MRSA, is the true bad actor.

“The American literature focused first on MRSA, but we’ve seen very similar, very severe cases with MSSA [methicillin-susceptible S. aureus] PVL-positive and MRSA PVL-positive infections,” Pablo Rojo, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“It is only because at the beginning there were so many MRSA cases in the States that they thought that was the driver of the disease. It is still unclear. There is still a discussion. But I wanted to bring you my opinion and that of many other authors that it’s mostly PVL-associated,” added Dr. Rojo of Complutense University in Madrid.

He was senior author of a multinational European and Israeli prospective study of risk factors associated with the severity of invasive community-acquired S. aureus infections in children, with invasive infection being defined as hospitalization for an infection with S. aureus isolated from a normally sterile body site such as blood, bone, or cerebrospinal fluid, or S. aureus pneumonia. They identified 152 affected children, 17% of whom had severe community-acquired invasive S. aureus, defined by death or admission to a pediatric intensive care unit due to respiratory failure or hemodynamic instability.

The prevalence of PVL-positive S. aureus infection in the overall invasive infection group was 19%, while 8% of the isolates were MRSA. while MRSA was not associated with a significantly increased risk. The other independent risk factors for severe outcome were pneumonia, with an adjusted 13-fold increased risk, and leukopenia at admission, with an associated 18-fold risk (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 Jul;22[7]:643.e1-6.).

Of note, the virulence of PVL stems from the pore-forming toxin’s ability to lyse white blood cells. Because a leukocyte count is always available once a patient reaches the ED, severe leukopenia as defined by a count of less than 3,000 cells/mm3 at admission becomes a useful early marker of the likely severity of any case of S. aureus invasive disease, according to Dr. Rojo.

He highlighted four key syndromes involving severe invasive S. aureus infection in previously healthy children and adolescents that entail a high likelihood of being PVL positive and should cause physicians to run – not walk – to start appropriate empiric therapy. He also described the treatment regimen that he and other European thought leaders recommend for severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections.

The microbiologic diagnosis of PVL can be made by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) to detect the toxin in an S. aureus isolate, by a rapid monoclonal antibody test, or by polymerase chain reaction to detect PVL genes in an S. aureus isolate. But don’t wait for test results to initiate treatment because these are high-mortality syndromes, he advised.

“Many people tell me, ‘My lab doesn’t have a way to diagnose PVL.’ And it’s true, it’s not available in real life at many hospitals. My message to you is that you don’t need to wait for a microbiological diagnosis or the results to come back from a sample you have sent to the reference lab in the main referral center. We can base our diagnosis and decision to treat on clinical grounds if we focus on these four very uncommon syndromes involving invasive S. aureus infection. I think if you have any child with these symptoms you have to manage them on the assumption that PVL is present,” said Dr. Rojo, principal investigator of the European Project on Invasive S. aureus Pediatric Infections.

The four key syndromes

The four syndromes are severe S. aureus pneumonia, S. aureus bone and joint infections with multiple foci, S. aureus osteomyelitis complicated by deep vein thrombosis, and invasive S. aureus infection plus shock.

- Severe S. aureus pneumonia. Investigators at Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France, have done extensive pioneering work on severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections in children. In an early paper, they highlighted the characteristics that distinguish severe PVL-positive pneumonia: it typically occurs in previously healthy children and adolescents without underlying comorbid conditions, and it is often preceded by a influenza-like syndrome followed by an acute severe pneumonia with hemoptysis. Mortality was very high in this early series, with nearly half of the patients being dead within the first several days after admission (Lancet. 2002 Mar 2;359[9308]:753-9).

- Severe osteomyelitis. Investigators at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, were among the first to observe that osteomyelitis caused by PVL-positive strains of S. aureus are associated with more severe local disease, with multiple affected areas, bigger abscesses, a greater systemic inflammatory response, and more surgeries required compared with osteomyelitis caused by PVL-negative S. aureus (Pediatrics. 2006 Feb;117[2]:433-40).

- Osteomyelitis with deep vein thrombosis. When a child hospitalized for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis due to S. aureus develops difficulty breathing, that’s a red flag for a severe PVL-positive infection involving deep vein thrombosis. Indeed, investigators at the Leeds (England) General Infirmary have reported that deep vein thrombosis in the setting of S. aureus osteomyelitis is associated with a greater than eightfold increased likelihood of a PVL-positive infection (Br J Hosp Med [Lond]. 2015 Jan;76[1]:18-24). Also, patients with PVL-positive osteomyelitis and deep vein thrombosis are prone to formation of septic emboli.

- Osteomyelitis with septic shock. The Lyon group compared outcomes in 14 pediatric patients with PVL-positive S. aureus osteomyelitis and a control group of 17 patients with PVL-negative disease. All 14 PVL-positive patients had severe sepsis and 6 of them had septic shock. In contrast, none of the controls did. Median duration of hospitalization was 46 days in the PVL-positive group, compared with 13 days in controls (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007 Nov;26[11]:1042-8).

Treatment

No randomized trials exist to guide treatment, but Dr. Rojo recommends the protocol utilized by the Lyon group: a bactericidal antibiotic – vancomycin or a beta-lactam – to take on the S. aureus, coupled with a ribosomally active antibiotic – clindamycin or linezolid – to suppress the PVL toxin’s virulence expression. The French group cites both in vitro and in vivo evidence that clindamycin and linezolid in their standard dosing have such an antitoxin effect (Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017 Oct;30[4]:887-917).

In addition, Dr. Rojo recommends utilizing any of the commercially available intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products on the basis of work by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who have demonstrated that these products contain functional neutralizing antibodies against S. aureus leukocidins. This observation provides a likely explanation for anecdotal reports of improved outcomes in IVIG-treated patients with toxin-associated staphylococcal disease (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Oct 24;61[11]. pii: e00968-17).

Challenged as to when specifically he would use IVIG in light of the global shortage of immunoglobulins, Dr. Rojo replied: “Not in every invasive S. aureus infection, but in serious infections that are PVL positive. I think if you have a child with one of these four syndromes who is in a pediatric ICU, you should use it. I mean, the mortality is around 30% in healthy children, so you would not stop from giving it. The risk of giving IVIG is very low, no side effects, so I highly recommend it for these severe cases.”

He reported having no financial conflicts.

MALMO, SWEDEN – Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus gets the blame in the Americas as the main cause of a great wave of community-acquired severe invasive staphylococcal infections in children and adolescents during the past nearly 2 decades, but many European pediatric infectious disease specialists believe that Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a frequent co-traveler with MRSA, is the true bad actor.

“The American literature focused first on MRSA, but we’ve seen very similar, very severe cases with MSSA [methicillin-susceptible S. aureus] PVL-positive and MRSA PVL-positive infections,” Pablo Rojo, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“It is only because at the beginning there were so many MRSA cases in the States that they thought that was the driver of the disease. It is still unclear. There is still a discussion. But I wanted to bring you my opinion and that of many other authors that it’s mostly PVL-associated,” added Dr. Rojo of Complutense University in Madrid.

He was senior author of a multinational European and Israeli prospective study of risk factors associated with the severity of invasive community-acquired S. aureus infections in children, with invasive infection being defined as hospitalization for an infection with S. aureus isolated from a normally sterile body site such as blood, bone, or cerebrospinal fluid, or S. aureus pneumonia. They identified 152 affected children, 17% of whom had severe community-acquired invasive S. aureus, defined by death or admission to a pediatric intensive care unit due to respiratory failure or hemodynamic instability.

The prevalence of PVL-positive S. aureus infection in the overall invasive infection group was 19%, while 8% of the isolates were MRSA. while MRSA was not associated with a significantly increased risk. The other independent risk factors for severe outcome were pneumonia, with an adjusted 13-fold increased risk, and leukopenia at admission, with an associated 18-fold risk (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 Jul;22[7]:643.e1-6.).

Of note, the virulence of PVL stems from the pore-forming toxin’s ability to lyse white blood cells. Because a leukocyte count is always available once a patient reaches the ED, severe leukopenia as defined by a count of less than 3,000 cells/mm3 at admission becomes a useful early marker of the likely severity of any case of S. aureus invasive disease, according to Dr. Rojo.

He highlighted four key syndromes involving severe invasive S. aureus infection in previously healthy children and adolescents that entail a high likelihood of being PVL positive and should cause physicians to run – not walk – to start appropriate empiric therapy. He also described the treatment regimen that he and other European thought leaders recommend for severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections.

The microbiologic diagnosis of PVL can be made by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) to detect the toxin in an S. aureus isolate, by a rapid monoclonal antibody test, or by polymerase chain reaction to detect PVL genes in an S. aureus isolate. But don’t wait for test results to initiate treatment because these are high-mortality syndromes, he advised.

“Many people tell me, ‘My lab doesn’t have a way to diagnose PVL.’ And it’s true, it’s not available in real life at many hospitals. My message to you is that you don’t need to wait for a microbiological diagnosis or the results to come back from a sample you have sent to the reference lab in the main referral center. We can base our diagnosis and decision to treat on clinical grounds if we focus on these four very uncommon syndromes involving invasive S. aureus infection. I think if you have any child with these symptoms you have to manage them on the assumption that PVL is present,” said Dr. Rojo, principal investigator of the European Project on Invasive S. aureus Pediatric Infections.

The four key syndromes

The four syndromes are severe S. aureus pneumonia, S. aureus bone and joint infections with multiple foci, S. aureus osteomyelitis complicated by deep vein thrombosis, and invasive S. aureus infection plus shock.

- Severe S. aureus pneumonia. Investigators at Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France, have done extensive pioneering work on severe PVL-positive S. aureus invasive infections in children. In an early paper, they highlighted the characteristics that distinguish severe PVL-positive pneumonia: it typically occurs in previously healthy children and adolescents without underlying comorbid conditions, and it is often preceded by a influenza-like syndrome followed by an acute severe pneumonia with hemoptysis. Mortality was very high in this early series, with nearly half of the patients being dead within the first several days after admission (Lancet. 2002 Mar 2;359[9308]:753-9).

- Severe osteomyelitis. Investigators at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, were among the first to observe that osteomyelitis caused by PVL-positive strains of S. aureus are associated with more severe local disease, with multiple affected areas, bigger abscesses, a greater systemic inflammatory response, and more surgeries required compared with osteomyelitis caused by PVL-negative S. aureus (Pediatrics. 2006 Feb;117[2]:433-40).

- Osteomyelitis with deep vein thrombosis. When a child hospitalized for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis due to S. aureus develops difficulty breathing, that’s a red flag for a severe PVL-positive infection involving deep vein thrombosis. Indeed, investigators at the Leeds (England) General Infirmary have reported that deep vein thrombosis in the setting of S. aureus osteomyelitis is associated with a greater than eightfold increased likelihood of a PVL-positive infection (Br J Hosp Med [Lond]. 2015 Jan;76[1]:18-24). Also, patients with PVL-positive osteomyelitis and deep vein thrombosis are prone to formation of septic emboli.

- Osteomyelitis with septic shock. The Lyon group compared outcomes in 14 pediatric patients with PVL-positive S. aureus osteomyelitis and a control group of 17 patients with PVL-negative disease. All 14 PVL-positive patients had severe sepsis and 6 of them had septic shock. In contrast, none of the controls did. Median duration of hospitalization was 46 days in the PVL-positive group, compared with 13 days in controls (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007 Nov;26[11]:1042-8).

Treatment

No randomized trials exist to guide treatment, but Dr. Rojo recommends the protocol utilized by the Lyon group: a bactericidal antibiotic – vancomycin or a beta-lactam – to take on the S. aureus, coupled with a ribosomally active antibiotic – clindamycin or linezolid – to suppress the PVL toxin’s virulence expression. The French group cites both in vitro and in vivo evidence that clindamycin and linezolid in their standard dosing have such an antitoxin effect (Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017 Oct;30[4]:887-917).

In addition, Dr. Rojo recommends utilizing any of the commercially available intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products on the basis of work by investigators at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who have demonstrated that these products contain functional neutralizing antibodies against S. aureus leukocidins. This observation provides a likely explanation for anecdotal reports of improved outcomes in IVIG-treated patients with toxin-associated staphylococcal disease (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Oct 24;61[11]. pii: e00968-17).

Challenged as to when specifically he would use IVIG in light of the global shortage of immunoglobulins, Dr. Rojo replied: “Not in every invasive S. aureus infection, but in serious infections that are PVL positive. I think if you have a child with one of these four syndromes who is in a pediatric ICU, you should use it. I mean, the mortality is around 30% in healthy children, so you would not stop from giving it. The risk of giving IVIG is very low, no side effects, so I highly recommend it for these severe cases.”

He reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2018