User login

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

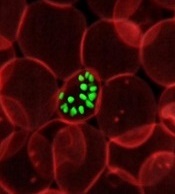

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()